Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 4 - (22º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 593 to 596

MANAGEMENT OF HIPERNASALITY CAUSED BY ADENOIDECTOMY

Author(s):

* Patrícia Junqueira;

** Ana Cristina N. Vaz;

*** Claudia Peyres López;

**** Shirley N. Pignatari;

***** Luc Louis Maurice Weckx

Keywords: adenoidectomy, hipernasality, and speech therapy

Abstract:

Hipertrophic adenoid is a frequent cause of obstruction of the upper respiratory tract and may lead to a mouth breathing condition. in some cases, surgical procedures such as adenoidectomy and or tonsillectomy are necessary to reestablish the nasal breathing. We have observed that following adenoidectomy, many children present with vocal hipernasality, even when there is no previous history or complains.In this paper, the authors describe a case of severe hipernasality following adenoidectomy, as well as detailed steps of the speech therapy approach. The risks and sequelae of this vocal condition related to adenoidectomy are also discussed.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Infant years are marked as a time of respiratory problems, especially owing to the enlargement in pharyngeal and/or palatine tonsils common in these children.

Owing to its location, pharyngeal tonsil, if increased, can cause obstruction of upper airways, leading to oral breathing1. In some cases, adenoidectomy and/or adenotonsillectomy are indicated to remove the obstructing factor, enabling nasal breathing.

In the ambulatory of the Discipline of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology at UNIFESP/EPM, we have conducted speech and voice assessments of children submitted to adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy before and after surgery. We have observed that some children even without complaints and/or vocal abnormalities preoperatively develop hypernasal vocal quality after adenoidectomy 12.

This hypernasality presented by certain patients tends to reduce and even disappear spontaneously after the first postoperative months. Some authors1, 2, 13 attribute this fact to the type of velopharyngeal closure presented by the child, in which velar contact is made with lymphoid tissue. Thus, when the tissue is removed, the diameter of the nasopharynx is increased and the muscles of the velopharyngeal mechanism need to employ compensation maneuvers of velar stretching to prevent air leak through the nose.

Our experience in seeing children postoperatively after adenoidectomy has shown that most of the patients present hypernasal voice in this period and it tends to improve spontaneously on average 3 months after the surgery1, 2, 13. However, we observed during the follow up that one of the patients maintained vocal hypernasality even after this period.

The purpose of the present study was to describe the clinical case of the patient so that healthcare professionals that follow up patients with mouth breathing with indication for adenoidectomy can identify and diagnose the risks or sequelae to the patient, adopting a more appropriate intervention in these cases.

CASE REPORT

K.C.M., female, 7-year-old patient, reported respiratory difficulties when first came to the Ambulatory of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP-EPM. After physical examination and nasolaryngoscopy, she was recommended to undergo adenoidectomy. There were no structural abnormalities of the velopharyngeal sphincter mechanism.

In the speech assessment conducted preoperatively, we observed mouth breathing, lip, tongue and cheek hypotonia, open lips at rest and tongue on the floor of the mouth. Speech was characterized by omission of consonant groups and presence of articulation imprecision, that is, the movable articulator (the mandible) did not precisely touch the passive articulator. We did not find abnormalities concerning vocal quality. As to history data, the mother did not report nasal reflux episodes or vocal resonance abnormalities.

One month after the surgical procedure we conducted a reevaluation in which we identified nasal breathing, appropriate lip and tongue posture and presence of mild to moderate vocal hypernasality. Speech abnormalities were maintained and the mother referred that after surgery, the daughter's voice was "nasal".

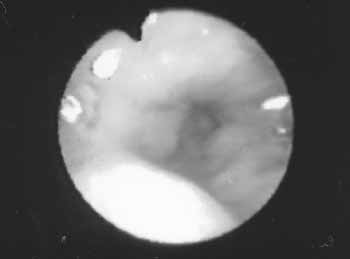

Thus, we conducted a nasolaryngoscopic exam that revealed circular velopharyngeal closure with gap on the central region (Figure 1). We did not find any other structural abnormalities.

Three months after the surgery, in the reevaluation the patient presented similar hypernasal vocal pattern. Therefore, we indicated speech therapy in order to install the sounds that were omitted (consonant groups), increase precision of movements necessary to produce speech, and direct the mouth airflow to the mouth cavity, as advocated by Altmann (1997) to minimize vocal hypernasality.

Upon placing the articulation points adequately and directing the airflow to the mouth cavity, there is greater muscle movement in all the velopharyngeal region2. Therefore, sphincter closure is facilitated and hypernasality tends to reduce or even be eliminated.

Therapy was conducted for 4 months with weekly periodicity, and each session lasted 30 minutes. We used the procedure advocated by Altmann (1985) named "Articulation Therapy of Oral Airflow", whose principle is to place the mouth airflow into all speech sounds. We used the device named "scape scope" that consists of a glass cylinder with a small foam ball inside it and a tubing coupled to the cylinder. The objective is to capture any airflow that penetrates into the cylinder and make the ball go up, facilitating the perception of the mouth airflow to be used in speech sound production 2. We asked the mother to make the exercises at home with the child so that the exercises could be incorporated into spontaneous speech patterns.

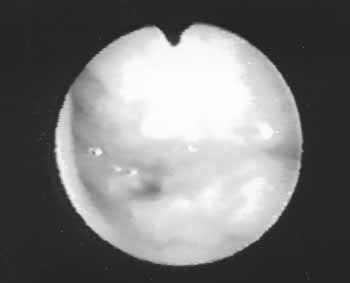

At the end of the period, we observed significant improvement of the articulation and the patient had incorporated into speech the practiced sounds, as well as reduced significantly vocal hypernasality. Nasolaryngoscopic assessment made upon discharge showed satisfactory closure of velopharyngeal sphincter, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Image obtained from nasofibroscopic exam of the patient during prolonged emission with phoneme /s/, preoperative period of adenoidectomy, in which we can see circular velopharyngeal closure with gap on the central region.

Figure 2. Image obtained from nasofibroscopic exam of the patient during prolonged emission with phoneme /s/, postoperative period of adenoidectomy, in which we can see satisfactory closure of the velopharyngeal sphincter.

DISCUSSION

Normal closure of velopharyngeal mechanism occurs mainly by the movement of the levator veli muscle backwards and upwards, to the direction of the posterior pharyngeal wall. There is also participation of the pharyngeal lateral muscles provided by the action of the pharyngeal constrictor muscle, in some types of closure. In children, this type of closure is caused by the close contact of the levator veli muscle with the pharyngeal tonsil, adhered to the pharyngeal posterior wall, or even the veli and the lateral wall1.

The involution of the tonsils, together with the downward and forward growth of the maxilla in relation to the skull base, force the velopharyngeal sphincter (VPS) to gradually get adapted.

However, such adaptation does not always occur, giving raise to cases of velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) and the consequent voice hypernasality 12. When the pharyngeal tonsil is hypertrophied, many structural abnormalities of velar functioning can not be observed. Among them, we can mention: submucous cleft, occult submucous cleft, neurological problems, inconsistent velopharyngeal closure or of functional origin, skull base or cervical spine abnormalities, among others1, 12.

When there is indication of the surgery to remove the pharyngeal tonsils, a careful examination of the velopharyngeal complex should be made to identify the risk cases for development of hypernasal speech1. Careful nasopharyngoscopic exam to visualize the nasal aspect of the veli should be performed as routine not only to identify, locate and measure the leak that is not perceptible through the speech sound, but also to rule out the existence of occult submucous fissure or V palate1, 3.

In some cases, postoperative hypernasality can occur even without the identification of structural risk factor in the preoperative assessment, such as in the case described here; only in 30% of the cases that have vocal hypernasality after adenoidectomy the origin is unknown3, 8. The time for spontaneous recovery is not clearly defined either and it can be even one year after the surgery4. Some studies reported the benefits of conservative therapy but when hypernasality is maintained, indication is normally surgical, such as placement of cartilage on the posterior pharyngeal walls and, as a last resort, pharyngoplasty 5. However, our experience has shown that the recovery occurs on average 3 months after the surgery. Therefore, we have indicated speech therapy after this period in order to improve directing of mouth airflow to enhance vocal hypernasality. Literature reports suggested that hypernasality is more common in patients submitted to adenoidectomy than to tonsillectomy11, although the incidence of adenotonsillectomy is 1:30006, 14.

Many studies have demonstrated that the articulation work is capable of directly influencing closure of VPS 7, 9. Among the various techniques described is the Articulation Therapy with Oral Airflow, by Altmann (1997), whose objective is to make adequate the articulation contacts and to direct the airflow coming from the lungs to the mouth cavity. The advantages of the use of the technique in cases of VPI are: reduction of hypernasality and improvement of VPS 2, which was observed in the case described by the present study.

CLOSING REMARKS

Hypernasality after the removal of the pharyngeal tonsils deserve attention of healthcare professionals owing to the impact it can have in communication of patients submitted to surgical procedures. Therefore, careful assessment of the velopharyngeal complex by a multidisciplinary team is essential during the preoperative period, especially when there are suspicions of submucous cleft, occult submucous cleft, neurological problems, inconsistent velopharyngeal closure or of functional origin, skull base or cervical spine abnormalities, among others1, 12. In addition, it is essential that the professional notified the parents and the patients about the risks of having hypernasality after the surgery.

Postoperative speech intervention proved to be effective to instruct and treat the patient reported in this case study.

REFERENCES

1. Almeida CIR. Adenóides e amígdalas: a grande polêmica. In: Altmann EBC. Fissuras lábio-palatinas. Carapicuíba: Pró-Fono; 1997. p. 471-84.

2. Altmann EBC, Vaz ACN, Farias RALN; Faria MBSP, Khoury RBF, Marques RMF. Tratamento fonoaudiológico. In: Altmann EBC. Fissuras Labiopalatinas. Carapicuiba: Prófono; 1997. p. 367-403.

3. Croft CB, Shprintzen RJ, Daniller A, Lewin ML. The occult submucous cleft palate and the musculus uvulae. Cleft Palate J 1978; 15:150-4.

4. Donnelly MJ. Hipernasality following adenoid removal. Ir J Med Sci 1994;163(5):225-7.

5. Fernandes DB, Grobbelaar AO, Hudson DA, Lentin R. Velopharyngeal incompetence after adenotonsillectomy in non-cleft patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac surg 1996;34(5):364-7.

6. Gibbs AG. Hypernasality (rhinolalia aperta) following tonsil and adenoid removal. J Laryng Otol 1958;72:433-451.

7. Golding-Kushner K. The effect of articulation therapy on velopharyngeal closure. Paper presented at the Fourth International Congress on Cleft Palate and Related Craniofacial Anomalies. Acapulco, 1981.

8. Goode RL, Ross J, Calif PA. Velopharyngeal insufficiency after adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryng 1972;96:223-26.

9. Hoch L, Golding-Kushner K, Siegel-Sadewitz VL, Sphrintzen RJ. Speech therapy. Seminars Speech Lang 1986;7:313-24.

10. Mason RM, Warren DW. Adenoid involution and developing hypernasality in cleft palate. Journal of speech and hearing disorders 1980;xlv:469-79.

11. Ren YF, Isberg A, Henningsson G. Velopharyngeal incompetence and persistent hypernasality after adenoidectomy in children without palatal defect. Cleft palate craniofac J 1995;32(6):476-82.

12. Shprintzen RJ. Insuficiência Velofaríngica In: Altmann EBC. Fissuras Labiopalatinas. Carapicuíba: Prófono; 1997.

13. Shprintzen RJ, Lencione RM, Mccall GN, Skolnick ML. A three dimensional cinefluoroscopic analysis of velopharyngeal closure during speech and non speech activities in normal. Cleft Palate J 1974;11:412-28.

14. Witzel MA, Rich RH, Margar-Bacal F, Cox C. Velopharyngeal insufficiency after adenoidectomy: an 8 year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1986;37:15-20.

[1] Speech Therapist, Ph.D. in Human Communication Disorders, UNIFESP/EPM.

[2] Speech Therapist, Master in Human Communication Disorders, UNIFESP/EPM.

[3] Speech Therapist, Master in Human Communication Disorders, UNIFESP/EPM.

[4] Ph.D. in Otorhinolaryngology, Professor at UNIFESP/EPM.

[5] Full Professor, UNIFESP/EPM.

Study conducted at Federal University of São Paulo - Medical School of São Paulo/SP

Discipline of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology.

Address correspondence to: Rua dos Otonis, 684 - Vila Clementino - São Paulo/SP

Tel/Fax: (55 11) 5539-7723