Year: 2012 Vol. 78 Ed. 5 - (18º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 116 to 120

Non sindromic cleft lip and palate: relationship between sex and clinical extension

Author(s): Daniella Reis Barbosa Martelli1; Renato Assis Machado2; Mário Sérgio Oliveira Swerts3; Laíse Angélica Mendes Rodrigues4; Sibele Nascimento de Aquino5; Hercílio Martelli Júnior6

DOI: 10.5935/1808-8694.20120018

Keywords: cleft lip, cleft palate, female, male.

Abstract:

Cleft lip and/or palate represent the most common congenital anomaly of the face.

AIM: To describe the correlation between non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate and gender, and its severity in the Brazilian population.

METHODS: Cross-sectional study, between 2009 and 2011, in a sample of 366 patients. The data was analyzed with descriptive statistics and multinomial logistic regression with a 95% interval to estimate the likelihood of the types of cleft lip and/or palate affecting the genders.

RESULTS: Among the 366 cases of non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate, the more frequent clefts were cleft lip and palate, followed respectively by cleft lip and cleft palate. The cleft palates were more frequent in females, while the cleft lip and palate and cleft lips only predominated in males. The risk of cleft li in relation the cleft palate was 2.19 times in males when compared to females; while the risk of cleft lip and palate in relation to cleft palate alone was 2.78 times in males compared to females.

CONCLUSION: This study showed that there were differences in the distribution of the non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate between males and females.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Non syndromic cleft lip and/or palate (NSCL/P) (OMIM # 119530) represents the most frequent congenital malformation in the head or neck region with a prevalence of approximately 1:700 live births worldwide. Its prevalence varies according to ethnicity (Africans: 0.3:1,000; Europeans: 1.3:1,000; Asians: 2.1:1,000; Native Americans: 3.6:1,000) and socioeconomic level1,2. In Brazil, NSCL/P prevalence ranges from 0.19 to 1.54:1,000 live births3-6. NSCL/P etiology, which involves both genetic and environmental factors, is highly complex, and the molecular basis remains largely unknown7,8.

Affected children with NSCL/P need multidisciplinary care from birth until adulthood and have higher morbidity and mortality throughout life than do unaffected individuals9,10. Findings of studies have shown an increased frequency of structural brain abnormalities11 and that many children and their families are affected psychologically to some extent12.

NSCL/P can be broadly divided into those that affect the lip only, both the lip and palate, or the palate alone. Although cleft lip and cleft lip and palate are traditionally collapsed to form the single group of cleft lip with or without cleft palate, data suggest that these two categories may have different genetic causes and should, when feasible, be analysed separately13,14.

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate is most frequent in males, and isolated cleft palate is most typical in females, across various ethnic groups; the sex ratio varies with severity of the cleft15, presence of additional malformations, number of affected siblings in a family, ethnic origin, and possibly paternal age16,17. In white populations, the sex ratio for cleft lip with or without cleft palate is about 2:1 (male:female)15. In this study we examine the relation between NSCL/P and sex and severity of the clef in Brazilian population.

METHOD

A cross-sectional study was conducted with a population of 366 patients treated at the reference Service who presented non sindromic cleft lip and/or palate, between 2009 and 2011. This reference Service of the Brazilian Health Department comprises a multidisciplinary team of health care specialists, including plastic and dental surgeons, dentists, psychologists, pediatricians, genetic counseling, nutritionists and speech therapist.

After anamnesis, physical examination was conducted to establish the kind of cleft and anatomical structures involved. The clefts were categorized in 3 parts, with the incisive foramen reference18: (1) cleft lip: include complete or incomplete clefts pre foramen, uni or bilateral; (2) cleft lip and palate: include uni or bilateral transforamen clefts and pre or post foramen clefts and (3) cleft palate: include all post foramen clefts, completes or incompletes. The patients were evaluated by professionals with large experience with oral cleft.

All patients were screened for the presence of associated anomalies or syndromes, and only those identified to have non sindromic cleft lip and/or palate were included in this study. Patients who received any surgical treatment to correct the clefts were excluded of this analysis thus carriers out of proposed classification and with cleft syndromes.

The information collected was stored in a database and analyzed using statistical program PASW® version 18.0 for windows (Chicago, USA). Data were analyzed with chi-square test (χ2) and using the multinomial logistic regression with an interval of 95% estimated the chances of the types of cleft lip and/or palate between sex. This study was submitted to the Ethics Committee in Research of the University (# 129/2009). All patients or their familiars were informed about the study's purpose before they consented to participate.

RESULTS

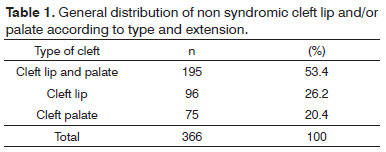

Among the 366 patients treated during 2009-20011, 199 (54.5%) were male and 167 (45.6%) were female. Of the total number of participants (n = 366), 25 (6.83%) presented a positive history of cleft in their families and 341 (93.16%) presented a negative history. Table 1 demonstrated the cleft distribution according to type and extension. The more frequent clefts were cleft lip and palate (53.4%), followed respectively by cleft lip (26.2%) and cleft palate (20.49%).

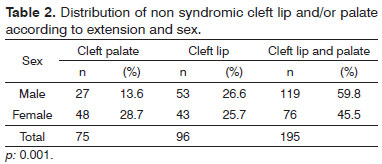

In Table 2, it is possible to observe the distribution of NSCL/P according to sex.

There were differences between the cleft groups according to the sex. It is noted that cleft palate were more frequent in females (28.7% versus 13.6%; 1.77:1), while the cleft lip and palate (59.8% versus 45.5%; 1.56:1) and cleft labial (25.7% versus 26.6%; 1.23:1) predominated in males (p = 0.001; χ2).

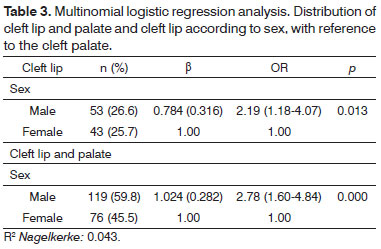

The Table 3 showed the multinomial logistic regression analysis. It turns out that the risk of occurrence of cleft lip in relation the cleft palate was 2.19 times in males compared to females. While the risk of cleft lip and palate in relation cleft palate was 2.78 times in males compared to females.

DISCUSSION

A recent work suggested that there has been a gross underestimation of the consequences of being born with cleft lip and/or palate19. Individuals born with cleft lip and/or palate, have a shorter lifespan, with increased risk for all major causes of death, when compared with individuals born without clefts10. Contributing to these higher mortality rates are probably psychiatric disorders and cancer. Cleft lip and/or palate, increases the risk of hospitalization for psychiatric diseases in adults10. Furthermore, there is an increased occurrence of breast and brain cancer among adult females born with cleft lip and/or palate, and an increased occurrence of primary lung cancer among adult males born with cleft lip and/or palate20,21.

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate is listed as a feature of more than 200 specific genetic syndromes, and isolated cleft palate is recorded as a component of more than 400 such disorders22. The proportion of orofacial clefts associated with specific syndromes is between 5% and 7%23. Although the presence of a genetic component both in syndromic and nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate has been clearly demonstrated, only in a limited portion of a cases the genes involved have been so far identified, and in many cases, only preliminary data are available about the mechanisms leading to the craniofacial defects in the presence of a specific gene alteration24. In this present study, we evaluated only patients with NSCL/P. All cases with associated or syndromes were excluded.

Different studies have been conducted worldwide to evaluate NSCL/P distribution, often resulting in varying prevalence rates10,25. In a Brazilian population study, we showed predominance of cleft lip and palate (52.6%), followed by cleft lip (33.12%) and cleft palate (14.28%)26. In most published studies, the percentage of subjects with cleft lip and palate has been higher compared to that of cleft lip or cleft palate alone, including the Brazilian studies27,28. The findings of the present study reveal that of the 366 patients with NSCL/P, the prevalence of cleft lip and palate (53.4%) was significantly higher that of cleft lip (26.2%) and cleft palate (20.49%). Epidemiological data across different populations have shown that the prevalence of cleft palate is generally lower than that of cleft lip and palate and cleft lip and families at high risk for one type of cleft are not at increased risk for the other type, reflecting the distinct developmental origins of each form of cleft29. Occasionally, however, both cleft lip and palate and cleft lip and cleft palate can occur within the same pedigree, suggesting at least some overlap in the aetiology of these two broader categories of clefts2.

In Japanese populations, cleft lip and palate shows a significant male excess, but this excess is not seen for cleft lip alone30. In white populations, the male excess in cleft lip with or without cleft palate becomes more apparent with increasing severity of cleft and less apparent when more than one sibling is affected in the family31,32. By contrast, the male predominance in cleft lip with or without cleft palate is smaller when the infant has malformations of other systems16, and findings of one large study suggest predominance in females when the father is age 40 years or older33. Here, we showed that cleft palate were more frequent in females (28.7% versus 13.6%; 1.77:1), while the cleft lip and palate (59.8% versus 45.5%; 1.56:1) and cleft labial (25.7% versus 26.6%; 1.23:1) predominated in males (p = 0.001). It was also noted, by analyzing multinomial logistic regression that the risk of occurrence of cleft lip in relation the cleft palate was 2.19 times in males compared to females. While the risk of cleft lip and palate in relation cleft palate was 2.78 times in males compared to females. These results shall ratify the found in the literature on foreign populations15,30.

CONCLUSION

This study observed a predominance of cleft lip and palate (53.4%), followed respectively by cleft lip (26.2%) and cleft palate (20.49%). There were also differences between the cleft groups according to the sex. It is noted that cleft palate were more frequent in females, while the cleft lip and palate and cleft labial predominated in males. The risk of occurrence of cleft lip in relation the cleft palate was 2.19 times in males compared to females. While the risk of cleft lip and palate in relation cleft palate was 2.78 times in males compared to females. Molecular and genetic studies are needed to better understand the differences between the types of oral clefts and sex.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from The Minas Gerais State Research Foundation - Fapemig, Brazil, and from National Council for Scientific and Technological Development-CNPq, Brazil (HMJ and MSOS).

REFERENCES

1. Carinci F, Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Zollino I, Pezzetti F. Human genetic factors in non syndromic cleft lip and palate: an update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(10):1509-19.

2. Jugessur A, Shi M, Gjessing HK, Lie RT, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, et al. Genetic determinants of facial clefting: analysis of 357 candidate genes using two national cleft studies from Scandinavia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4):e5385.

3. de Castro Monteiro Loffredo L, Freitas JA, Grigolli AA. Prevalence of oral clefts from 1975 to 1994, Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2001;35(6):571-5.

4. Martelli-Junior H, Porto LV, Martelli DR, Bonan PR, Freitas AB, Della Coletta R. Prevalence of nonsyndromic oral clefts in a reference hospital in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, between 2000-2005. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21(4):314-7.

5. Nunes LMN, Queluz DP, Pereira AC. Prevalência de fissuras labiopalatais no município de Campos dos Goytacazes-RJ, 1999-2004. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2007;10(1):109-16.

6. Rodrigues K, Sena MF, Roncalli AG, Ferreira MA. Prevalence of orofacial clefts and social factors in Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23(1):38-42.

7. Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, Dixon MJ, Shaw WC. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 2009;374(9703):1773-85.

8. Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty HT, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(3):167-78.

9. Ngai CW, Martin WL, Tonks A, Wyldes MP, Kilby MD. Are isolated facial cleft lip and palate associated with increased perinatal mortality? A cohort study from the West Midlands Region, 1995-1997. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17(3):203-6.

10. Christensen K, Juel K, Herskind AM, Murray JC. Long term follow up study of survival associated with cleft lip and palate at birth. BMJ. 2004;328(7453):1405.

11. Nopoulos P, Langbehn DR, Canady J, Magnotta V, Richman L. Abnormal brain structure in children with isolated clefts of the lip or palate. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(8):753-58.

12. Berk NW, Marazita ML. The costs of cleft lip and palate: personal and societal implications. In: Wyszynski DF, ed. Cleft lip and palate: from origin to treatment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. p.458-67.

13. Harville EW, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT, Vindenes H, Abyholm F. Cleft lip and palate versus cleft lip only: are they distinct defects? Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(5):448-53.

14. Rahimov F, Marazita ML, Visel A, Cooper ME, Hitchler MJ, Rubini M, et al. Disruption of an AP-2alpha binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip. Nat Genet. 2008;40(11):1341-7.

15. Mossey PA, Little J. Epidemiology of oral clefts: an international perspective. In: Wyszynski DF, ed. Cleft lip and palate: from origins to treatment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. p.127-58.

16. Mossey P, Castillia E. Global registry and database on craniofacial anomalies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

17. Martelli DRB, Cruz KM, Barros LM, Silveira MF, Swerts MSO, Martelli Júnior H. Maternal and paternal age, birth order and interpregnancy interval evaluation for cleft lippalate. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(1):107-12.

18. Spina V, Psillakis JM, Lapa FS, Ferreira MC. Classificação das fissuras lábio-palatinas. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med S Paulo. 1972;27(2):5-6.

19. Vieira AR. Unraveling human cleft lip and palate research. J Dent Res. 2008;87(2):119-25.

20. Bille C, Winther JF, Bautz A, Murray JC, Olsen J, Christensen K. Cancer risk in persons with oral cleft -- a population-based study of 8,093 cases. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(11):1047-55.

21. Yildirim M, Seymen F, Deeley K, Cooper ME, Vieira AR. Defining predictors of cleft lip and palate risk. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2012;91(6):556-61.

22. Wong FK, Hagg U. An update on the aetiology of orofacial clefts. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10(5):331-6.

23. Tolarová MM, Cervenka J. Classification and birth prevalence of orofacial clefts. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75(2):126-37.

24. Stuppia L, Capogreco M, Marzo G, La Rovere D, Antonucci I, Gatta V, et al. Genetics of syndromic and nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(5):1722-6.

25. Derijcke A, Eerens A, Carels C. The incidence of oral clefts: a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34(6):488-94.

26. Martelli-Júnior H, Bonan PR, Santos RC, Barbosa DR, Swerts MS, Coletta RD. An epidemiologic study of lip and palate clefts from a Brazilian reference hospital. Quintessense Int. 2008;39(9):749-52.

27. Freitas JA, Dalben Gda S, Santamaria M Jr, Freitas PZ. Current data on the characterization of oral clefts in Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18(2):128-33.

28. Martelli DR, Bonan PR, Soares MC, Paranaíba LR, Martelli-Júnior H. Analysis of familial incidence of non-syndromic cleft lip and palate in a Brazilian population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15(6):e898-901.

29. Jugessur A, Farlie PG, Kilpatrick N. The genetics of isolated orofacial clefts: from genotypes to subphenotypes. Oral Dis. 2009;15(7):437-53.

30. Fujino H, Tanaka K, Sanui Y. Genetic study of cleft lips and cleft-palates based upon 2,828 Japanese cases. Kyushu J Med Sci. 1963;14:317-31.

31. Fogh-Andersen P. Inheritance of harelip and cleft palate. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1942.

32. Niswander JD, MacLean CJ, Chung CS, Dronamraju K. Sex ratio and cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Lancet. 1972;2(7782):858-60.

33. Rittler M, López-Camelo J, Castilla EE. Sex ratio and associated risk factors for 50 congenital anomaly types: clues for causal heterogeneity. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(1):13-9.

1. MSc. Professor of Semiology - State University of Montes Claros. PhD student - State University of Montes Claros - Unimontes.

2. Dentistry student. (Scientific Initiation - CNPq scholarship holder).

3. PhD (Full professor at Unifenas).

4. MSc - Graduate Program in Health Sciences - Unimontes.

5. MSc. Phd Student in Stomatopathology - State University of Campinas - Unicamp).

6. PhD. Full Professor.

Graduate Program in Health Sciences - Center of Biological and Health Sciences - Unimontes.

Send correspodence to:

Hercílio Martelli Júnior

Rua Olegário da Silveira, nº 125/201, Centro

Montes Claros - MG. Brazil. CEP: 39400-020

E-mail: hmjunior2000@yahoo.com

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System - Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on May 22, 2012.

And accepted on July 23, 2012. cod. 9216.

This study was supported by grants from The Minas Gerais State Research Foundation - Fapemig, Brazil, and from National Council for Scientific and Technological Development-CNPq, Brazil (HMJ and MSOS).