Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 5 - (1º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 584 to 588

Langerhans cells in human vocal fold mucosa: immunohistochemical study

Author(s):

João Aragão Ximenes Filho1,

Francisco Valdeci Ferreira2,

Francisco Dário Rocha Filho3,

Domingos Hiroshi Tsuji4,

Luiz Ubirajara Sennes5

Keywords: vocal cords/ anatomy & histology, langerhans cells, immunohistochemistry.

Abstract:

Introduction: Langerhans Cells (LC) are a type of dendritic cells that have functions which involves antigen presentation and the stimulation of a T cell response. They represent about 4% of the laryngeal epithelial cells. Objective: The aim of this study was to identify the presence of LC in the epithelium of the vocal folds, to compare their subpopulations, as well as to compare the capacity of four immunohistochemistry markers. Study Design: Experimental. Material and Method: Six cadavers, 3 men and 3 women, were studied. Analysis of vocal folds and skin paraffin blocks stained with commercially available polyclonal S-100, vimentin, CD-68 and fascin were done. After histological analysis, Student t test and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were accomplished in the statistical study. Results and Conclusions: It was possible to identify the presence of LC in the epithelium of the human vocal folds in no smokers of both sexes. Fascin, vimentin and CD-68 were superior markers of LC than S-100 polyclonal antibody in vocal folds (p=0,01) and in the skin (p=0,02). It was also possible to identify three different subpopulations of LC in the vocal folds and skin. However, just in the skin it was observed larger amount in the basal layer of the epithelium statistically significant.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cells (LC) are a type of dendritic cells that play the role of antigen presenters and are found in lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues. In non-lymphoid tissues, they are specialized in defense and processing of foreign antigen 1. Thus, they present vital immunological function that involves presentation of antigen and stimulation of immune response mediated by thymus-dependent lymphocytes (lymphocyte T)2.

Even though they are well known and have been studied in skin tissues and oral mucosa, only in 1994, THOMPSON and GRIFFIN3 described the presence of LC inside squamous stratified epithelium of normal human vocal folds and estimated that they represent about 4% in proportion of laryngeal epithelial cells in humans. The cells (LC) play an important role in immune response because they secrete cytokines and express surface receptors. They are important components of the immune system, participating in the activation of lymphocytes T, given that they are the main antigen-presenting cells in the immune system.

The importance of this finding increased when it was described that LC low-density laryngeal tumors presented worse prognosis when compared to LC high-density tumors 4. Currently, laryngeal tumors represent about 5% of all new cases of cancer, except for skin cancer. Approximately 6,600 new cases of laryngeal cancer are registered in Brazil every year, causing about 3,500 deaths annually in the country 5. These tumors are more common in subjects aged between 50 and 60 years 6.

However, these cells are hardly identified by conventional histological techniques, requiring immunohistochemical marking. Many different markers have been used, hindering comparison of results from different studies. Thus, we decided to conduct a study whose main objectives were:

1. To identify the presence of LC in the epithelium of intermembranous portion of vocal fold epithelium and skin of non-smokers of both genders;

2. To compare four immunohistochemical markers concerning their capacity to detect these cells on the vocal epithelium and on the skin;

3. To observe and compare subpopulations of LC present on the vocal fold and skin of these subjects by making multiple immunohistolabeling.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Sample

After approval of the Research Ethics Committee (CAPPesq) of Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo, we studied six cadavers from the Service of Death Checking of Sao Paulo, University of Sao Paulo (SVO); we studied 3 male and 3 female subjects from October 2003 to January 2004.

The characteristics of cadavers studied were race, gender, age, height, weight, and cause of death. From medical charts at SVO, we collected information such as profession, use of drugs and previous diseases. Table 1 sums up this information together with other data collected from the death certificate issued by SVO.

We included only cadavers whose larynx could be removed up to 18 hours after death and those that were completely macroscopically preserved, without lesion or structural damage. We excluded cadavers that had been previously submitted to orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, tracheotomy, laryngeal surgery, radiotherapy on the cervical-facial region, smokers, or had presented some laryngeal disease during life. We excluded cadavers with history of thyroid disease or chronic use of corticoids, in addition to women who died during pregnancy or immediately after birth. Professional voice users were not included in the study either. Cadavers that had diffuse dermatological damage and/or inguinal region injury were equally excluded.

Method

Larynx harvesting

In cadavers selected according to the criteria above described, we conducted skin incision on the upper thoracic region and made a cutaneous flap. We removed the larynx in bloc after cranial section of the hyoid bone, at the level of the fourth tracheal ring. In the Laboratory of Medical Investigation (LIM 32), Medical School, University of Sao Paulo, we made dissection and opening of the larynx by the posterior aspect with coronal posterior section, perpendicular to the free margin of the vocal fold, containing three layers (epithelium, corium and muscle), removing fragments of 0.3 x 0.5 x 0.3cm. Next, we identified the material with the SVO number.

Skin harvesting

From the same cadaver, we removed the larynx, also taking a portion of skin located 2cm laterally to the right inguinal fold at the level of pubis. At LIM32, we removed the central fragment of skin sample, measuring 0.3 x 0.5 x 0.3 cm and identified it with the SVO number. We selected this region to prevent the use of areas exposed to sun or attrition, which could have interfered in the results.

Preparation of pieces for immunohistochemical study

From blocks of paraffin with vocal fold and skin samples, we made 5 m sections prepared on the slides with glue (Cascurez 1:4). Next, after antigenic recovery with wet heat and endogenous peroxidase blockage, we applied primary antibodies, comprising four histiocytic and reticular cell markers: CD68, Vimentin, Fascin and Protein S-100. We also applied secondary antibody and demonstration (streptABC, DAKO Corporation -Carpinteria USA), developed by DAB, in addition to extra-staining with diluted hematoxyllin. In each battery we had positive external controls (cases of Langerhans histiocytosis) and negative controls (by exclusion of primary antibodies).

Analyzed Parameters

Slide interpretation considered the presence of Langerhans cells specifically marked and their location.

1. Initially, we had total count of LC present in each of the analyzed specimens. We studied 10 sequenced fields, with ocular 12x and objective of 40x (magnification of 480x) both on skin sample and vocal fold, in each of the studied samples.

2. Next, we defined three distinct areas for classification of LC subpopulations: basal region - when the cell was in direct contact with basal lamina (LB) of epithelium, suprabasal region - when the cell was on the epithelium, but without contact with the LB; and subepithelial region - when the cell was below LB. We quantified the cells present in each one of the regions in 10 sequenced fields with the same magnification above referred.

We used optical Microscope Leica DMLS, three-ocular with coupled image recording system.

Statistical analysis

We conducted Kolmogorof-Smirnov test, which was positive in all studied parameters. Next, we collected means of these parameters and applied t Student test to compare LC by field in each used immunohistochemical marker. To compare the three studied subpopulations, we used variance studies (ANOVA one-way). We considered significance level of 95% (p<0.05). Statistical softwares used were SPSS® version 10.0 to Windows and Microsoft Excel®.

RESULTS

Results are summarized in two tables. In Table 2, we demonstrate the comparison of Langerhans cells with different immunomarkers evidencing that Protein S-100 presented statistically significant difference compared to the others on both vocal fold and skin. In table 3, we present the comparison of different subpopulations of Langerhans cells on the vocal folds and skin with different markers, demonstrating that only basal layer of skin was different from the others.

DISCUSSION

Laryngeal cover epithelium is not uniform, presenting stratified paved epithelium on the ventral face and dorsal portion of the epiglottis, in addition to the vocal folds, whereas on the other regions it is respiratory epithelium, with cilia that bend towards the pharynx 7. On the free border of the vocal fold, stratified paved epithelium comprises one or two basal cell layers and up to six layers of superficial flat cells 8.

Squamous stratified epithelium is mitotically formed by basal cells that are taken by continuous proliferation towards the epithelium surface. In this process, it modifies its shape from column or cuboid to paved epithelium 9. From the surface, the cell is removed by abrasion.

Among these cells, there are also Langerhans cells (LC), a type of dendritic cells that take part in the immune system. It is believed that LC capture antigens found in the epidermis and then migrate from the epidermis to subepithelial lymph nodes. They get to the paracortical region of lymphatic ganglia and activate lymphocytes T in the restricted area of the major histocompatibility complex class II 10.

Thus, it is possible to morphologically separate three subpopulations of LC in the epithelium and underlying region: basal layer cells, suprabasal cells and subepithelial cells. In this study, we observed greater amount of LC on the basal layer both of skin and vocal folds. However, when we statistically compared the three subpopulations, we noticed that there were statistically more cells on the basal layer only of the skin. It may represent higher cell turnover of LC on the skin or more marked immune function on the skin. However, the model we studied did not allow us to clarify this question.

In the present study, we used a reduced sample because of the high cost of immunohistochemical markers and used four of them to identify the level of adequacy, sensitivity and specificity concerning skin (more widely investigated model) and larynx.

Therefore, it was possible to statistically demonstrate that protein S-100, one of the most frequently used markers to identify LC 3,4,11,12, presents the lowest level of detection of these cells among the four used markers (Table 2). Fascin, a packaging protein of actin of 55-kd initially isolated from HeLa cells, presents high specificity and sensitivity in labeling dendritic cells 13. The presence of fascin in dendritic cells is no surprise once this protein is similar to actin and it is involved in the formation of stripes of microfilament, important for the mobility of these cells 13. In our study, despite the fact it did not statistically differ from vimentin or CD-68, fascin presented higher indexes of LC labeling and better staining definition. Thus, it shall be adopted in future studies on oncology currently in development.

The effects of tobacco on LC are also uncertain. BARRET et al.14 (1991) stated that in smokers, there is increased density of LC in the oral epithelium. DANIELS et al.15 (1992), however, demonstrated reduction in the occurrence of LC on the oral mucosa as a result of smoking. In the cervix, there is decrease of LC density owing to smoking 16, 17. In the study of LC in normal laryngeal epithelium 3, the authors used 7 larynges, 5 of non-smokers, 1 of a smoker and 1 unknown. In the present study, we decided not to include smokers to exclude this bias.

CONCLUSION

We could conclude that:

1. It was possible to identify the presence of LC on the cover epithelium of the intermembranous portion of vocal folds in non-smoking humans of both genders;

2. Fascin, vimentin and CD-68 proved to be good markers of LC both on vocal fold epithelium and on skin, whereas S-100 protein had statistically less labeling power;

3. It was possible to identify three different subpopulations of LC present both on the vocal fold and on the skin of these subjects, in addition to detecting that most of the cells were located on the basal epithelial layer.

REFERENCES

1. Austyn JM. Dendritic cells. Curr Opin Hematol 1998; 5:3-15.

2. Braathen LR, Bjerke S, Thorsby E. The antigen presenting function of human Langerhans cells. Immunobiology 1984; 168:301-12.

3. Thompson AC, Griffin NR. Langerhans cells in normal and pathological vocal cord mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol 1994; 115:830-2.

4. Gallo O, Libonati GA, Gallina E, Fini-Storchi O, Giannini A, Urso C, Bondi R. Langerhans cells related to prognosis in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991; 117:1007-10.

5. GLOBOCAN 2000 - Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide, Version 1.0. IARC Cancer Base. No 5. Lyon, IARC, 2001.

6. Gould WJ, Sataloff RT, Spiegel JR. Voice Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993.

7. Junqueira LC, Carneiro J. Histologia básica. 7a ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara; 1990.

8. D'Andretta Neto C. Estudo e importância das alterações epiteliais da laringe. São Paulo, Dissertação (Mestrado). Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, 1984.

9. Stiblar-Martin?i? D. Histology of laryngeal mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 1997; 527:138-41.

10. Teunissen MB. Dynamic nature and function of epidermal Langerhans cells in vivo and in vitro: a review, with emphasis on human Langerhans cells. Histochem J 1992; 24(10):697-716.

11. Hammar S, Bockus D, Remington F, Bartha M. The widespread distribution of Langerhans' cells in pathologic tissues. Hum Pathol 1986; 17:894-905.

12. Kurihara K, Hashimoto N. The pathological significance of Langerhans cells in oral cancer. J Oral Pathol 1985; 14(4):289-98.

13. Pinkus GS, Pinkus EL, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S, Mosialos G, Said JW. Fascin, a sensitive new marker for Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease. Evidence for a dendritic or B cell derivation? Am J Pathol 1997; 150(2):543-61.

14. Barrett AW, Williams DM, Scott J. Effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on the Langerhans cell population of human lingual epithelium determined using a monoclonal antibody against HLADR. J Oral Pathol Med 1991; 20:49-52.

15. Daniels TE, Chou L, Greenspan JS, Grady DG, Hauck WW, Greene JC, Ernster VL. Reduction of Langerhans cells in smokeless tobacco-associated oral mucosal lesions. J Oral Pathol Med 1992; 21:100-4.

16. Poppe WA, Drijkoningen M, Ide PS, Lauweryns JM, Van Assche FA. Langerhans' cells and L1 antigen expression in normal and abnormal squamous epithelium of the cervical transformation zone. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1996; 41:207-13.

17. Barton SE, Maddox PH, Jenkins D, Edwards R, Cuzick J, Singer A. Effect of cigarette smoking on cervical epithelial immunity: a mechanism for neoplastic change? Lancet 1988; 17;2(8612):652-4.

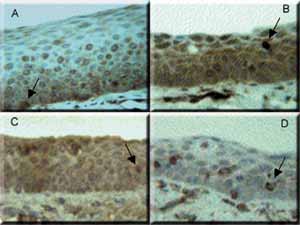

Photo 1 - Epithelium of human vocal fold stained with four different immunomarkers. A: Fascin. B: CD-68. C: Protein S-100. D: Vimentin. The arrows indicate Langerhans cells. In A, epithelium basal layer and in the others, suprabasal. 400x magnification.Table 1 - Cadaver data obtained from the Service of Death Checking, University of Sao Paulo.

Table 2 - Comparison of human Langerhans cells with different immunomarkers, by histological field with 480x magnification, evidencing that Protein S-100 statistically differed from the others, both on vocal fold and skin.Table 3 - Comparison of different subpopulations of human Langerhans cells on the vocal folds and skin with different markers (p values), demonstrating that the basal layer was different from the others only on the skin.

1 Ph.D. in Otorhinolaryngology, FMUSP. Researcher physician, Hospital do Câncer do Ceará - ICC.

2 Joint Professor, Department of Pathology, Medical School, Federal University of Ceará. Coordinator of the Laboratory of Pathology, Hospital do Câncer do Ceará - ICC.

3 Joint Professor, Department of Pathology, Medical School, Federal University of Ceará.

4 Full Professor, Responsible for the Group of Voice, Division of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, HC-FMUSP.

5 Full and Associate Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, FMUSP; Director of Service of Buccopharyngolaryngology, HC-FMUSP.

Study conducted together by Hospital do Câncer do Ceará - Instituto do Câncer do Ceará (ICC), and Division of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo (HC-FMUSP).

Address correspondence to: João Aragão Ximenes Filho. Rua Paula Ney, 700/1202; CEP 60140-200, Fortaleza-CE. Tel: (55 85) 268 3641.

e-mail: joaoximenesf@bol.com.br