Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 4 - (19º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 561 to 564

Primary small-cell carcinoma of paranasal sinuses: A case study

Author(s):

Maura C. Neves1,

Raquel A. Tavares1,

Fernando Veiga Angélico Jr2,

Richard L. Voegels3,

Ossamu Butugan4

Keywords: Key words: small cell carcinoma, paranasal sinuses.

Abstract:

Primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (SCC) of the sinusal tract are extremely uncommon and aggressive tumors. Although the lungs are the most prevalent site of these tumors, this report focuses on the involvement of an extrapulmonary site, the paranasal sinuses. Methods: We report the case of a female patient with a primary small cell carcinoma of maxillary sinus. A literature discussion with all reported cases of SCC and its metastasis, treatment and survival expectations are included.

![]()

Introduction

Small-cell carcinomas are aggressive tumors frequently found in the lungs. Primary extrapulmonary sites are extremely rare. However, with increasing diagnostic improvements, detection has become possible. The sites involved include esophagus, pharynges, minor salivary glands, nasal fosses and paranasal sinuses, pancreas, uterus, bladder, prostate, breast, gastric-intestinal tract, among others1,4.

Recent studies show that 23% of these tumors are found in the otorhinolaryngological tract, among which 8.5% are in the paranasal sinuses5. They present mean 5-year survival of 13%, which corroborates its aggressive behavior with high recurrence and local/distant metastases rates, regardless of surgical, radio or chemotherapy treatments.

Nearly 4% of small-cell carcinoma patients do not present an evident pulmonary or mediastinal site.

A case of small-cell carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses is described, followed by discussion of literature data, including disease epidemiology as well as patients' clinical history, evolution, treatment and prognosis.

Case Study

GCF, 31-year-old Caucasian woman, arrived at our service with 5-month history of flu-like symptoms and nasal obstruction and partial improvement with the use of symptomatic medication. In the last two months, edema, hyperemia and pain on the right maxillary region were also present. The patient received antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin and potassium clavulanate, 500 mg PO/TID) and corticoid therapy for 14 days, with discrete response. Since then, paresthesia on the right maxillary region, upper right arch and upper right lip was observed.

Presence of headache, fever, yellow rhinorrhea, nasal itching, coryza, sneezing, epistaxis, coughing, epigastralgia, and retrosternal pyrosis were not present. Patient denied smoking and alcohol abuse.

Otorhinolaryngological examinations, including oroscopy, anterior rhinoscopy and otoscopy, were within normal limits and neck nodes were not palpable. Discrete facial asymmetry with painless edema and hyperemia of the right maxillary region were also verified.

Nasofibroscopy revealed right septum deviation, with narrow right middle meatus and absence of purulent secretion in the right nasal cavity. The left nasal cavity, rhinopharynx, oropharynx and larynx were not affected. Masses in the nasal cavities or in the middle meatus were not identified.

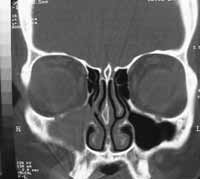

Computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses revealed covered right maxillary sinus, bone erosion in the right orbit floor and invasion of the anterior wall of the right maxillary sinus. Intra-orbital foramens were apparently not involved (Figures 1-2).

Patient was then submitted to excision biopsy of the mass, via Caldwell-Luc, on the right. Clinical pathology analysis revealed malignant small-cell neoplasia with extensive necrotic areas.

Immediately after surgery, the patient presented edema and hyperemia in the right maxillary region, as expected. Symptoms fully regressed up to the 7th day after surgery. On the same occasion, discrete improvement of paresthesia of the maxillary region, upper dental arch and upper right lip was observed, although paresthesia was not fully resolved.

Radiological tumor staging and investigation on its possible pulmonary nature included thoracic computed tomography, bone scintilography, abdominal ultrasound and a second CT scan of the facial and neck sinuses, which presented normal results.

Follow-up included surveillance examinations for cervical metastases and local relapse through magnetic resonance imaging of the paranasal sinuses and neck CT scan. Up to the sixth month after surgery, the patient remained asymptomatic and without signs of recurrence.

The patient was not submitted to radio or chemotherapy.

Discussion

Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma (SCC) was formerly described in 1930 and accounts for 4% of all SCCs. It is a rare condition and, due to its epidemiology and clinical behavior, it has been established as a distinct clinical entity among lung SCCs.

Differently from other lung SCCs, it has not been possible to associate extrapulmonary cancer with smoking habit, although 63% of SCC cases are of smokers 5. Morphologically, they show similar features, such as presence of neurosecreting granules associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Clinically, similarities include development of metastases to regional lymph nodes, liver and bones.

The present case was about a 31-year-old woman. Apparently, there is no gender predominance 6-8 in the available literature and age at diagnosis varies - between 20 and 70 years, mean age of 506-8.

Clinically, our case presented nasal obstruction as the main symptom, which is in accordance with other authors' findings9. However, for Ordonez et al.7 and Kameya et al.6, epistaxis is the most frequent symptom, followed by facial pain, exophtalmus and nasal obstruction.

Most studies (including ours), report the maxillary sinus as one of the main sites affected by this type of tumor6-8. However, various authors have referred to these tumors as deriving from other sinuses, such as ethmoid and frontal6. For Ordonez et al.7, the nasal cavity is the main origin of SCC, while the middle and upper conchae are the most affected locations. Pierce et al.10 reviewed 33 cases of this tumor and verified that most of them (26 cases) appeared in the nasal cavity close to the middle concha.

Diagnosis of small-cell carcinomas should be radio and histologically determined. Complementary exams, such as computed tomography and nasofibroscopy of paranasal sinuses are useful to determine tumor extension and site of origin.

According to Franzen et al., in a review2, most head and neck SCCs are primary extrapulmonary tumors rather than pulmonary metastases. However, as differential diagnosis criteria are the same for both affected sites, the diagnosis of primary pulmonary site should always be excluded. The difference between head and neck primary SCC and a pulmonary metastatic tumor, as well as site and staging, are crucial criteria for therapeutic and prognostic settlement.

Histologically, SCCs are undifferentiated trabecular-like carcinomas presenting extensive areas of necrosis and hemorrhage6,7. Some patients showed intracytoplasmatic granulations, which are responsible for the neuroendocrine characteristics of these tumors8.

Immunohistochemistry tests may be performed to investigate specific neuroendocrine markers. They include Cam 5.2, CD99, synaptophysin, chromogranin, protein S-100, neuro-specific enolase. Those are useful for differential diagnosis between SCC and other nasal cavity tumors, such as melanoma, neuroblastoma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Ewing's sarcoma and rabdomyosarcoma7. In the present study, those tests were conducted, though with inconclusive results.

Moreover, Ordonez et al.7 studied paranasal sinuses SCCs of 6 patients and the results were as follows: positive Cam 5.2, neuro-specific enolase and chromogranin in all patients; positive synaptophysin in 4 patients; negative S-100 protein in all tumors.

Treatment for these tumors has not been established yet. Due to tumor behavior, patients are usually submitted to aggressive therapies.

Galanis et al.5 have reported 7 cases of paranasal sinuses SCCs: 5 underwent only curative surgery and 1 received radiotherapy alone. Among all patients submitted to surgery, all of them presented local recurrence after average of 10 months. The patient who received radiotherapy was free from recurrences for 5 months and survived 11 months.

The study by Ordonez et al.7 included 6 patients: 5 underwent surgery, among which 3 received radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. After a 37-month follow-up, 4 patients relapsed or died as a result of metastases, regardless of the therapy received.

Silva et al.8 evaluated 10 patients: 70% had had local relapses or metastases after 3 years. Pierce et al.10 reviewed 33 cases of SCC and found metastases in 40% of the patients, which is consistent with 1-year survival rate of 50%.

Treatment of SCC in involves surgery, radio or chemotherapy - alone or associated. No treatment was superior to the other, but surgery associated or not with radiotherapy led to longer remission periods 9.

The most frequent metastatic sites included cervical lymph nodes and lungs6-8,10, bones6,8,10, central nervous system8 and liver 7,10.

Investigation on these neoplasias revealed that extrapulmonary tumors are morphologically similar to primary lung oat-cell tumors. Under electron microscope, some cases presented neurosecreting granules and may be associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, like small-cell lung tumors. Despite the heterogeneity observed in different sites, these tumors behave aggressively, presenting an average survival rate of less than a year after diagnosis and are prone to have lymph node metastases at other sites.

The impact of surgical, chemo and radiotherapy treatments on patients' survival is still unknown and is a common focus of investigations.

Closing Remarks

Small-cell carcinoma of paranasal sinuses is an uncommon neoplasia. Regardless of the morphological and immunohistochemical similarities with pulmonary SCC, it presents a distinct and aggressive behavior, as well as low survival rates.

Therefore, aggressive therapeutics involving surgery, radio and/or chemotherapy is preferred, although doubts regarding real benefits in patients' survival still remain. Careful evaluation and follow-up of these patients may help to elucidate such issues.

References

1. Cancer. Principles and practice of oncology. 4th edition.

2. Franzen A, Schmid S, Pfaltz M. Primary small-cell carcinomas and metastatic disease in the head and neck. HNO 1999 Oct; 47(10):912-7.

3. Ibrahim NBN, Briggs JC, Corbishley CM. Extrapulmonary oat cell carcinoma. Cancer 1984; 54:1645-61.

4. Weiss MD, Fries HO, Taxy JB, Braine H. Primary small-cell carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol 1983; 109:341-3.

5. Galanis E, Frytak S, Lloyd R. Extra-pulmonary small-cell carcinoma. Cancer 1997; 79(9):1729-36.

6. Kameya T, Shimosato Y, Adachi I, Abe K, Ebihara S, Ono I. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the paranasal sinus. Cancer 1980; 45:330-9.

7. Ordonez BP, Caruana SM, Huvos AG, Shah JP. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Human Pathology 1998; 29(8):826-32.

8. Silva EG, Butler JJ, Mackay B, Goepfert H. Neuroblastomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the nasal cavity. Cancer 1982; 50:2388-405.

9. Remick SC, Ruckdeschel LC. Extrapulmonary and pulmonary small-cell carcinoma: tumor biology, therapy and outcome. Med Pediatr Oncol 1992; 20(2):89-99.

10. Pierce ST, Cibull ML, Metcalfe MS, Sloan D. Bone-marrow metastases from small-cell cancer of the head and neck. Head & neck 1994; 16: 266-71.

Figure 1. Coronal section CT scan showing covered right maxillary sinus and erosion of the orbital floor.

Figure 2. Axial section CT scan showing invasion of the anterior wall of the right maxillary sinus.