Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 6 - (18º)

Artigo de Revisão

Pages: 896 to 902

Oral manifestations of lichen planus

Author(s):

Paula Moreno Fraiha 1,

Adriana Rung 2,

Christiane Spitz da Cruz 3,

Lília Mendes 4,

Mônica Barros Pereira 5,

Patrícia Tramontano Fraiha 6

Keywords: lichen planus, mucous-cutaneous disease, oral lesions

Abstract:

The lichen planus (LP) is a chronic mucous-cutaneous disease that oral lesions can precede or follow the skin lesion or even been the exclusive manifestation of it. Occurs commonly in adulthood of both sexes. It has unknown origin but today, the immunogenetic therapy is satisfactory for majority of the authors. The classic oral lesion characterizes with a forest with lines net on the posterior third part of buccal mucosa. The oral ulcers lesions are uncommon, but once arised, should be controlled by medical and/or dentist follow because they are sites of malignization. Usually oral lesions are asymptomatics. The diagnosis is made by the clinical appearance, view of lesion and biopsy results. The differential diagnostic is made with immuno diseases that involve the skin and mucous membranes. The treatment isn't specific. Includes steroids, tetracydines, immunomodulators, PUVA, dapsona, retinoids, interferon and thalidomide. The prognosis is good and the evolution is variable. Relapse of disease are common.

![]()

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototype of a group of dermatosis known as lichenoid disorders. They are characterized by histology damage to the deepest epidermal layer, reaching basal cells1.

It is a very well known disease that affects the oral mucosa especially in adults2, 3. They may follow, precede or be simultaneous to skin lesions or affect only the oral mucosa3. Lesions are detected by accident when the patient sees or feels them, or when they are noticed by the physician or dentist4.

The classical oral lesion is a whitish form on the posterior third of the jugal mucosa. However, there are many manifestations of this process and they can hinder the diagnosis in many situations3.

Its histology aspect is typical3. There are reticular damages that show mild hyperkeratosis or hyperparakeratosis, lysis of basal cells, thickness of basal lamina and mucositis owing exclusively to the lymphocytarian action5.

The pathogenesis is unknown, but it can involve some immune mechanism, since suppression of leukocytarian function and destruction of epithelial cells by immune-mediated mechanisms2 have been demonstrated. When it affects the same family, an increase in frequency of HLA-B76, HLA-A3, HLA-A5, HLA-Bw35, HLA-B8 to HLA-B16 7,8 is observed. The fact that LP has been described in monozygote twins in a relatively high frequency reinforces the idea of genetic predisposition to the disease6. There are hypotheses about the viral and psychogenic origin of the affection9. There may be correlation with diabetes, thyroid dysfunction and arterial hypertension. A correlation with lupus erythematosus and other immune-mediated diseases, such as liver disease, has been suggested3, 10. The emotional component, as well as trauma, toxic reactions, smoking and infections, can be predisposing factors1, 3, 4.

Cancer seems to be a complication of oral mucosa damage in about 5% of the cases3, 11. Some authors, such as Eisenberg et al. in 1985 to 1992 and Lovas et al. in 1989, suggested that malignant transformation would be related to an entity named lichenoid dysplasia and not oral LP. However, against this opinion, since the 70’s, there have been reports of LP oral cases controlled by various years that progressed to malignization of the lesions11.

Diagnosis is made by clinical aspects and biopsy2.

Up to today, there is no effective treatment4. Corticoid therapy is used to relieve the symptoms2, 4. Various drugs have been used as more or less successful2.

The prognosis is good, even though the lesions may persist indefinitely 4.

LITERATURE REVIEW

CONCEPT

LP is a chronic inflammatory disease2 that compromises the skin, annexes and mucosa9, 12. It is a rare affection13. It is characterized by pruritous papulous lesions2 that are very typical. The term lichen is originated from Greek leichén and Latin lichen, a word whose original meaning refers to some symbiotic forms of plants. Owing to the similarity with such botanical forms, the cutaneous mucosal lesions received this name1. The clinical findings of LP are summarized by the 4 P’s: purpura, polygonal, pruritus and papules 8.

HISTORY

In 1869, Erasmus Wilson gave the name LP, but the dermatosis had probably been described before by Hebra, as red lichen8,14,15. For much time it was considered a benign buccal pathology that suffered no degeneration16. In 1892, Kaposi reported a variant of the disease that presented blisters and named it red pemphigoid lichen 15. Wickham, in 1895, described the characteristic appearance of striae and dotting over the papules8,15. Histology findings were evidenced by Darier in 1909.8,15 In 1910, Hallopeau described one case of oral epidermoid carcinoma developed over a lesion of LP.16 Pinkus, in 1973, formally defined the typical lesion of the disease as a lichenoid tissue reaction1, 8, 15.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The distribution is the same for both genders and it is more frequent in the age range from 30 to 60 years1, 7, 9, 17. However, in tropical and subtropical countries, it was observed that younger patients are also affected1. Oral LP is extremely rare in children (2 to 3%)7, 17 and affects the typical areas or the lips8. There is no racial predominance8, 9, 15. It is believed that the prevalence is about 1% of the general population15.

Family LP has been described and it seems to be correlated with the HLA system and its onset is earlier than usual8.

ETIOPATHOGENESIS

Its etiology is unknown. There are hypotheses of viral and psychogenic origin. The psychological profile of patients with lichenoid reactions, including idiopathic oral LP, shows some characteristics, including exaggerated preoccupation with health and tendency to depression. A study conducted by Burkhart et al. in 1996 revealed that 51% of the patients with oral LP reported that the disease had begun during a situation of stress6, 8, 18, 19. Since there are deposits of immunoglobulin at linear position on the basal membrane and predominance of T helper lymphocytes on the superficial dermis, the immunological etiology is also coherent. This infiltration of T helper lymphocyte cells in the active disease happens at the dermal-epidermal junction and the deep dermis layer4. The production of cytokines is increased in LP concerning the levels of interleukins (IL) 1g, 4, 6 and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF).8 Interferon is produced by the activated lymphocytes that express keratinocytes to antigens HLA-DR and progress in damaged cells8. The damage of keratinocytes and liquefaction of basal cells may be mediated by cytokines and by the recruitment of cytotoxic T cells. The intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM 1) has a cellular diffuse distribution and is probably involved not only with recruitment of inflammatory cells but also the control of its functions, its retention and migration to the skin8. Studies demonstrated that T cells CD28 present in LP interact with a specific ligant (B7/BB1) found in dendrytic cells and keratinocytes 8. As a sequela of the inflammation induced by cytokines some structural changes are noticed. Disorders of the epithelial anchoring system are demonstrated by the presence of the stripped pattern of collagen VII in the deep connective tissue. Hemidesmosome becomes non-continuous in LP. The profile of keratin in the disease is modified with the expression of K6, K16 and K17 and there is hyperproliferation.

The issue is: what triggers the event? Some authors questioned that viral infections by the presence of human protein Mxa in the dermatosis and also by the evidence that oral LP could be associated with human papilloma virus. The way through which the virus acts as a foreign antigen inducing changes in the keratinocytes and how the basal anti-cellular antibodies can be part of the inflammatory response should still be investigated8. The demonstration of the basal anti-cellular antibodies in the disease, the detection of LP-specific antigen in 80% of the patients with LP, and the association of LP with a variety of auto-immune disorders suggest at least the possibility of combined cell and humoral pathogenesis8. There seem to be no uniform association between HLA and LP20.

Some drugs (anti-malaria, gold, bismuth, PAS, quinine, isoniazide, mercury and others) and photo developers (substitutes of paraphenylenodiamine) produce lichen planus-like lesions, that is, lichenoid eruptions but probably not related with the typical lichen planus 2. Sun radiation can originate the lesions or precipitate the onset of new lesions in cases of those who already have the disease9.

ORAL CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

As a single manifestation of LP, the oral disease affects 15 to 35% of the patients, but about 65% of the patients with the classical cutaneous disease present concomitantly the oral manifestation8. The jugal mucosa is commonly affected. The tongue, palate, lips and gums can be occasionally affected2. The involvement is normally symmetrical, but isolated damages were reported in the lips8.

The initial lesions are small papules that can be coalescent or show arrangements that result in a variety of clinical forms: reticular, atrophic, erosive, vesicular, papular, desquamation, and plaques2, 8, 14. The classical form is a reticular pattern that is easily recognized. It shows jugal mucosa apparently normal with white and gray lines, slightly elevated, that form the striae named Wickham’s striae 2,4. These lines are interconnected and form angles with reticular patterns4. The lesions vary in size, from few millimeters to involvement of the whole mouth mucosa4. In the tongue, the lesions surge usually as a fixed white plaque, strongly depressed, surrounded by normal mucosa1. The papula has its own characteristics: it is polygonal and has facets, it is shiny and has dots or striae on the surface 9. They are initially erythematous and later become purple, when affecting the skin9. In the oral mucosa, the lesions are whitish with a tree-like aspect, and erosions and ulcerations are rare2, 9. Ulcerative damages in the mouth are not common, but if present, they are an important site for observation and follow up because they are the base for epitheliomathous transformation1. They may reach the perianal mucosa, genitalia, pharynx, larynx, tympanic membrane, esophagus, stomach, colon and bladder1, 2, 9, 14. There are various studies published about the direct correlation between oral and vulvar LP14, 21.

The papular pattern consists of shinny white spots, sized as a pin head, slightly elevated, which are distributed in groups or diffusely spread on the oral mucosa. They can acquire the form of a solid whitish plate that when examined under enlargement shows that it consists of numerous smaller papules 4.

The clinical picture of desquamation gingivitis shows erosion, atrophy and desquamation of the gums, which in more severe cases can lead to mobility and avulsion of teeth. There is the same manifestation in cases of pemphigus or pemphigus vulgaris 22.

In direct immunofluorescence IgM is found in granulous deposits on the basal membrane. But IgG, IgA, C3 and fibrin can be present in the colloid bodies9, 23.

LP can be an acute form, with disseminated papules on the trunk and limbs and much pruritus, or a more insidious and chronic form, with few lesions followed by quick increase in number in some months9. The symptoms of lichen planus are very variable4. Oral lesions are normally asymptomatic and the patient can complain of burning sensation or even pain when presenting the erosive form2. Esophageal LP can cause dysphagia associated with oral LP.

The skin can suffer Koebner’s phenomenon, which reproduces the linear lesion by the trauma of scratching it or by other cause9.

Family LP is associated with atypical, linear, erosive and ulcerative lesions. The onset is normally earlier, 40% before the age of 30 years and with frequent recurrences8.

The history reveals remissions and exacerbation for years4.

An important issue is the development of squamous cell epithelioma in the lesions of lichen in the oral mucosa (1 to 10%)9. Men are more affected by mouth cancer and smoking is probably a co-factor that can contribute to this difference8. The development of cancer was described in patients with LP of erosive, atrophic and plaque types. The most affected site is the oral mucosa, but it can affect the tongue and lips as well8.

Classification of LP according to aspect of the lesion:

• Reticular

• Atrophic

• Papular

• Erosive

• Vesicular

• Desquamation

• Plaques

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is made through clinical observation, by visualization of the lesions, direct immunofluorescence and, in special, histology.

The material to be submitted to direct immunofluorescence should be collected from the lesion23. The biopsy reveals keratosis and parakeratosis, with basal cell destruction pattern4. It also shows focal hypergranulosis and irregular acanthosis, characterized by fissures in the epithelium and connective tissue9, 24. Inflammatory cells, normally lymphocytes, are present directly under the basal epithelium4-24. Interpapilar cones present the shape of saw teeth9, 25. There is vacuolization of basal cells9. In 37% of the cases there are Civatte’s corpuscles, which are degenerated basal keratinocytes.9,24

In the direct immunofluorescence, IgM is found in granulous deposits in the basal membrane. However, IgG, IgA, C3 and fibrin can be detected in the colloid bodies.9,23

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is made with secondary Lues, lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, lichen nitidus, lichen striatum, anular granuloma, leukokeratosis, drug lichenoid eruption, onychomycosis, scabies, pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris 8, 9, 12, 22, 26.

The difference between LP and lupus erythematosus is not easy. Histology factors help this distinction. Colloid bodies tend to be found deeply in the dermis, whereas in lupus erythematosus they are in the basal membrane. Findings of direct immunofluorescence in lupus erythematosus show linear IgG and C3 on the dermal-epidermal junction8.

In 1991, Boyd associated LP and liver disease. A recent study revealed the presence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies in 17 of 45 patients with LP. There was the same prevalence in men and women, affecting the patients with cutaneous disease only, only mucosa and cutaneous-mucosa lesions8. LP can appear after vaccination against hepatitis C.

A similar study with vaccinated HBV patients did not find enough subsidies to define a conclusion about the association between LP and hepatitis B27. It has also been reported in association with biliary cirrhosis8.

Figure 1. Patient with erosive LP in initial phase of gingival affection.

Figure 2. Patient after teeth removal owing to excessive mobility.

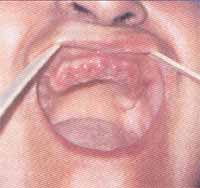

Figure 3. Patient with lichen planus presenting Wickham’s striae.

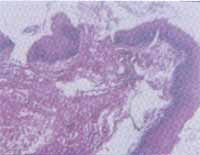

Figure 4. Fragment of mucosa with acanthosis and exocytosis with inflammatory infiltrate of lichen mononuclear type. The same infiltrate is observed in the subjacent corium.

TREATMENT

Up to today, there is no specific treatment against LP1.

Topical application of oral-base corticoid relieves the symptoms1, 13, 25, 28. Intra-lesional injection of the drug is indicated when the symptoms are severe, it improves pruritus and thickness of hypertrophic LP2, 8. Systemic corticoids can be used in ulcerative lesions4. The dose of prednisolone should be 15 to 20mg/day, sometimes even greater and the drug gradual suspension depends on clinical improvement8, 13.

Anti-septic mouthwash relieves discomfort of patients and anti-histaminic drugs can help reduce pruritus of the skin and mucosa2, 9.

Lundquist et al. demonstrated that PUVA is effective against oral LP2, 13, 25, 28.

Topical tetracycline for mouth washing (250mg dissolved in 100ml of water) twice to three times a day was used in patients with oral erosive LP. The lesions healed in 6 weeks and did not recur for one year, even though the LP remained clinically active29.

It is important to minimize the co-factors that can aggravate the disease such as trauma, smoking, infections by Candida, and to optimize oral hygiene8.

According to Capella and Finzi, in 2000, there are treatment approaches that are not in accordance with the FTN (Italian Therapeutic Formulary), but are used and many times, successfully. This type of therapy would be recommended when the advocated treatment does not work or when it can not be used for some specific reason30.

Up to 1995, the studies using oral and topical cyclosporine obtained conflicting results. They varied from no benefit to marked improvement14, 19. Capella and Finzi observed good results with topical cyclosporine in 5ml for mouth washing or local application, advocating their study in 2000 as an alternative of treatment30. Oral cyclosporine (5 to 6 mg/Kg/day) can be effective in the most severe forms of the disease8, 13, 29, 30.

Erosive forms can benefit from use of azathioprim, metotrexate and cyclophosphamide 8, 30. The use of such immunosuppressors is limited owing to high toxicity and high cost29.

Topical retinoid agents can be effective to treat oral LP13. An analog of vitamin D, KH 1060, has a significant immunosuppressant activity that modifies the epidermal cells of LP8, 30. Vitamin A and topical tetracycline are sometimes used against oral LP31. Hydroxichloroquine in 200 and 400mg/day for 3 to 6 months can be used8, 14.

Infection by Candida is common in these patients and because of that ketoconazole can be used. In cases of esophagitis, the association of ketoconazole and corticoids is indicated30.

The efficiency of grisofulvin in oral LP is currently under study.14,30

In elderly patients with long lasting erosive LP we can use dapsone. The same drug can be used in children with LP8, 14.

Interferon-2b can attenuate generalized LP after 8 to 10 months of treatment; efficacy of interferon in the treatment of viral hepatitis makes it a good alternative for patients that have hepatitis C virus8.

Thalidomide can be used as treatment for erosive LP. In 1985, Naafs and Faber published that they had succeeded in treating patients with LP using this drug. The patient was free from the disease after discontinuation of thalidomide treatment. More recently, Dereure et al. reported success in treating two patients with severe erosive oral LP who had not responded to conventional treatment. The patients responded quickly to daily doses of 150mg of thalidomide. The side effect they showed was moderate lymphopenia that resolved as soon as treatment was concluded. There may be headache, nausea, constipation, rash, sedation, erythema nodous-like reaction, weight gain and edema29.

The association of sulphametoxazole and trimethoprim proved to be effective in cases of acute LP. Metronidazole can also be used8, 30.

The surgery can be necessary in oral LP transformed into malignant lesion8. The reduced number of cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma directly related to LP require follow-up every 6 months, in addition to complete eradication of all potentially carcinogenic factors already known16. Laser cryosurgery can also be useful in LP8.

In addition, another miscellaneous of drugs have been used as alternative treatments to LP30.

EVOLUTION AND PROGNOSIS

Evolution is variable. Lesions can regress in weeks or month in acute cases or, in chronic forms, they can be insidious and last for years. Recurrences are common9. Cutaneous involvement in LP has a shorter course than the oral and hypertrophic variants8.

Prognosis is good. However, in the presence of squamous cell epithelioma, the prognosis is poor9.

DISCUSSION

Mucosa lesions are more common in LP and can be found in the absence of cutaneous lesions. They affect mainly adults, regardless of gender. It is much less common in Black patients. Its etiology is still not known and there are a number of advocated hypotheses. Jugal mucosa and the tongue are frequently affected, but the larynx, tympanic membrane and esophagus are rarely affected. Whitish striae on the oral mucosa are characteristic. On the tongue, the lesions are normally formed by fixed white plaques in the mucosa, slightly depressed below the normal mucosa. They can be present with episodes of desquamation gingivitis and if intense, they can cause mobility of teeth leading sometimes to teeth avulsion. We should, however, be always attentive to the characteristics of the disease and try to diagnose it more precisely, to start therapy as early as possible. We expect that future studies will provide a more specific therapy to the disease.

CLOSING REMARKS

LP is one of the most well known processes of the oral mucosa. The multiple forms of presentation of the disease hinder its clinical management, but almost always in some areas of the oral mucosa there is a classical lesion. Erosive lesions can be sites of late malignant transformation, which should be followed up periodically. In addition, there may be complications resultant from the treatment with corticoids, immunosuppressants and others that also require care.

Oral mucosa lesions can be difficult to diagnose. We should, therefore, be attentive to clearly differentiate between them and promote directed treatment to improve prognosis. We would like to emphasize the importance of an interdisciplinary approach in the follow-up of these patients.

REFERENCES

1. Black MM. Lichen Planus and Lichenoid Disorders in ROOK, A; Wilkinson DS, Ebling FSG. Blackwell Science; Textbook of Dermatology. 5a edition; England; 1995, p.1675-98.

2. Bluestone, Stool & Kenna. Inflammatory Disease of the Mouth and Pharynx , In: _______-, WB Saunders Company, Pediatric Otolaryngology vol II, 3a edition, Philadelphia, 1996, 1052-3.

3. Grinspan D. In: _______- Liquen rojo plano - Editorial Mundi. Enfermedades de la Boca. Tomo II, 1383-411.

4. Bluestone, Stool & Kenna. Idiopathic Conditions of the Mouth and Pharynx, In: ________-, WB Saunders Company, Pediatric Otolaryngology vol II, 3a edition, Philadelphia; 1996; 1088-91.

5. Eversole LR. Immunopathogenesis of Oral Lichen Planus and Recurrent Aphtomus Stomatitis. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, 1997; 16(4):284-94.

6. Burkhart NW, Burker EJ, Burkes EJ, Wolfe 1. Assessing the characteristics of patients with oral lichen planus. J.Am.Dent.Assoc. 1996; 127:648,651-2,655-6.

7. Howard R & Tsuchiya A. Adult Skin Disease in the Pediatric Patient. Dermatologic Clinics; July 1998;16(3):593-608.

8. Marshman G. Lichen planus. Australian Journal of Dermatology. 1998;39:1-13

9. Azulay & Azulay. Dermatoses Basicamente Papulosas. In: ______, Dermatologia. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 1997.p.109-214.

10. Ramírez-Amador VA, Esquivel-Pedraza L, Orozco-Topete R. Frequency of oral conditions in a dermatology clinic. International Journal of Dermatology 2000;39:501-5.

11. Villarroel M, Mata M, Salazar N, Tinoco P, Oliver M, Vaamonde J. Transformación Maligna Del Liquen Plano Bucal Vs Displasia Liquenoide. Acta odontol. Venez; 1997;35(2):61-3.

12. Moreno, Sonia, QCierio RS, Ramallo Y, Zelarayan LG. Líquen Plano. Arch. Argent. Dermatol. Enero-Febrero;2000;50(1):39-40.

13. Cribier B, Frances C, Chosidow 0. Treatment of Lichen Planus. Arch Dermatol, 1998, 134:1521-30.

14. Lewis FM. Vulval Lichen Planus. Br J Dermatol; 1998;138:569-75.

15. Pittelkow MR. Lichen Planus in 1c ed Editora Irwing M. Freedberg ... [ et al ];. Fitztatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine; 5a edition; 1999; 561-76.

16. Rebai-Chabchoub N & Reychler H. Lichen plan oral dégénéré. Acta Stomatologica Belgica vol.90, nº 3, p.163-69, 1993.

17. Herane MI & Hasson A. Lichen Planus en la Infancia. Dermatologia. 1992; 8(3):163.

18. Bergdahl J, Ostman P0, Anneroth G, Perris H, Skogland A. Psychological aspects of patients with oral lichen planus. Acta Odontol.Scand. 1995;53:236-44.

19. Sieg P, Von Domarus H, Von Zitzewitz V, Iven H, Fdrber L. Topical Cyclosporine in Oral Lichen Planus: A Controlled, Randomizzed, Prospective Trial., Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:790-4.

20. Duvic M. Influence of the HLA System on Disease Susceptibility in lc ed Editora Irwing M. Freedberg ... [ et al ];. Fitztatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine; 5a edition, 1999, 561-76.

21. Micheletti L, Preti M, Bogliato F et al. Vulval Lichen Planus in the Practice of Vulval Clinic. Br J Dermatol, 2000, 143:1349-50.

22. Ramos-e-Silva M & Fernandes NC. Afecçôes das Mucosas e Semimucosas. JBM, 2001; 80(3):50-66.

23. Gately III LE & Nesbitt it LT. Update On Immunofluorescent Testing In Bullous Diseases And Lupus Erythematosus. Dermatologic Clinics, January, 1994, 12(1):133-42.

24. Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Zhou X, Walsh L J, Bigby M. Oral Lichen Planus. Clinics in Dermatology, 2000;18:533-9.

25. Schiller PI, Flaig MJ, Puchta U, Kind P, Sander CA. Detection of clonal T cells in lichen planus. Arch. Dermatol.Res, 2000; 292:568-9.

26. Cucê LC & Festa Neto C. Líquen Plano. Manual de Dermatologia. Editora Atheneu, 1990:98-100.

27. Rebora A, Rongioletti F, Drago F, Parodi A. Lichen Planus as a Side Effect of HBV Vaccination. Dermatology, 1999, 198:1-2.

28. Boyd AS & Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J.Am.Acad.Dermatol. 2000; 25:593-619.

29. Popovsky JL. & Camisa C. New and Emerging Therapies for Diseases of Oral Cavity. Dermatologic Clinics, 2000; 18(1):113-25.

30. Capella GL & Finzi AF. Psoriasis, Lichen Planus, and Disorders of Keratinization: Unapproved Treatments or Indications. Clinics in Dermatology, 2000; 18:158-69.

31. Tüzün B, Tüzün Y, Wolf R. Oral Disorders: Unapproved Treatments or Indications. Clinics in Dermatology, 2000; 18:197-200.

32. Ho VC, Gupta AK, Ellis CN et al. Treatment of severe lichen planus with cyclosporine. J.Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1990;22:64-8.

33. Sharma R & Maheshwari V. Childhood Lichen Planus: A Report of Fifty Cases. Pediatric Dermatology, 1999; 16(5):345-8.

1,2,3,4,5,6 Staff Member of Clínica Professor José Kós.

Address correspondence to: Dra. Paula Moreno Fraiha

Rua Padre Elias Gorayeb 15 sala 606 - Tijuca - Rio de Janeiro - RJ - 20520-140

1 Coordinator of the Advanced Course in Clinical Otorhinolaryngology

Professor José Kós.

Article submitted on November 13, 2001. Article accepted on December 20, 2001.