Year: 2001 Vol. 67 Ed. 2 - (17º)

Relato de Casos

Pages: 253 to 259

Differential Diagnosis and Management in Pulsatile Tinnitus with Regard to Four Clinical Cases.

Author(s):

Eduardo A. Kaufmman*,

Luis C. Nadaf**,

Renato T. Souza***.

Keywords: pulsatile tinnitus, aberrant jugular bulb, tympanic glomus tumor

Abstract:

Pulsatile tinnitus can often be a diagnostic problem, since it is not common to find tinnitus synchronous with the patient's heartbeat. It can be the only symptom of life-threatening diseases. The main etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus are aberrant jugular bulb, intracranial hypertension, glomus tumors and carotid atherosclerosis. The presence of hearing loss or dizziness can direct the diagnostic evaluation. Fundoscopic examination should be done to exclude increased intracranial pressure. Cerebral angiography is required to diagnose vascular diseases. We present four patients with pulsatile tinnitus examined through otorhinolaringologic and audiologic evaluation, besides temporal bone image. Magnetic angioresonance and carotid digital arteriography were performed only in one patient. We diagnosed three cases of aberrant jugular bulb and one case of timpanic glomus tumor, which was surgically excised with improvement of tinnitus. The main objective of this study is to understand the importance of new image methods for the diagnostic of the many etiologies. The diagnostic evaluation helps us decide how to approach the different etiologies, sometimes only by giving orientation to the pacient in cases of aberrant jugular bulb, or deciding for surgery in cases of glomus tumors.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Pulsatile tinnitus is an uncommon otological symptom and frequently becomes a diagnostic problem to the ENT physician. Its precise diagnosis is essential because most of the patients have a treatable cause once it is identified. In addition, the likelihood of not diagnosing correctly may be catastrophic, because in some cases patients may experience severe intracranial pathologies26.

The purpose of the present study was to discuss differential diagnosis and intervention of pulsatile tinnitus, based on the report of four cases.

The symptom is perceived as sounds that vary in frequency, intensity and duration. Its unique characteristic is rhythm and there may be a subjective complaint or the association with objective findings26.

Pulsatile tinnitus originates from vascular structures as a consequence of the blood turbulence generated by the blood flow and the stenosis of vascular lumen, and they are synchronous with the patients' pulse. According to the originating vessel, pulsatile tinnitus may be classified as arterial or venous. The venous type is originated not only from primary venous pathologies, but also from conditions that produce intracranial pressure, through the transmission of arterial pulsation 16. Chart 1 sums up the most common etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus.

Despite any proposed classification, some etiologies represent diagnostic quandaries, such as cervical venous hum, high cardiac output, cardiac hum transmitted to cervical artery, abnormalities of the jugular bulb, high intracranial pressure, neoplasia involving the temporal bone, patent auditory tube and cholesterol granuloma of the middle ear. These diagnoses are normally made by exclusion.

Cervical venous hums may be perceived by the patient as pulsatile tinnitus. In the absence of auditory symptoms, it is considered a normal body sound that may be heard in most children or in adults with hyperdynamic circulation conditions13. Fifty-two percent of normal adults have cervical nervous hums that may be heard by auscultation. Conditions that result in increased cardiac output, such as anemia, thyrotocixity and pregnancy, may produce auditory symptoms4,29. Pulsatile tinnitus caused by high cardiac output is normally bilateral3.

Although hum is defined as a continuous sound, it is reinforced by the transmission of arterial pulsation, leading to the onset of subjective or objective pulsation, which is intensified by deep inspiration and reduced by Valsalva maneuver. When the head is moved towards the opposite side of the hum, its sensation is increased because of ipsilateral contraction of sternocleidomastoid muscle, increasing the diameter of contralateral internal jugular vein and consequently increasing its blood flow29.CHART 1 - Most common etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus.

Since 1914, enlarged jugular bulb, or jugular bulb, has been frequently recognized as the cause of unilateral pulsatile tinnitus, and it is difficult to make a clinical distinction from jugular glomus tumor16.

Right jugular bulb is normally larger than the left one28 and it is considered acceptable when its upper portion extends beyond the tympanic ring19. The level of jugular bulb seems to be the result of hypotympanus pneumatization and the position of the vertical segment of sigmoid sinus1. The more anterior the sigmoid sinus, the more acute will be the angle necessary to form the internal jugular vein, resulting, therefore, in relatively prominent jugular bulb17.

The cause of pulsatile bulb due to jugular megabulb is not clear. The retrograde transmission of pulsation of cardiac atrium and transtemporal transmission of intratemporal carotid artery are the two most widely accepted theories, although they are conflicting1,16. Variation of location of the sinuses of dura and bulb of the jugular have also been implicated3,14. However, none of these theories explain appropriately the sudden onset of pulsatile tinnitus3.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to understand etiologies of pulsatile tinnitus by means of the most recent procedures, such as imaging diagnosis angioresonance, and nuclear resonance imaging of the neck and temporal bone, and even by invasive methods, such as digital arteriography, according to the needs. Diagnostic elucidation, in turn, directed the intervention either to monitor patients with vascular anomalies, such as jugular megabulb, or to decide on surgical intervention, such as in cases of glomus tumors.

Some illustrative cases are presented in this study to show our current interventions for pulsatile tinnitus. From 1995 to 1999, four patients with pulsatile tinnitus were seen by our service. Videotoscopy, hearing acuity test, audiological assessment and tympanometry and CT scan of temporal bone and neck were performed in all patients. Carotid doppler ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic nuclear angioresonance and digital angiography were reserved for selected cases.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

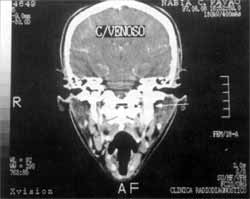

Twenty-six year-old woman complaining of headache and pulsatile tinnitus on the left ear, synchronized with the pulse, which had arisen during the fourth month of gestation, and remained the same during the past four years. She reported improvement of tinnitus with compression of lateral region of the neck at the level of the ipsilateral jugular vein and the flexion of the head to the same side. At the physical exam, she had normal otoscopy and audiometric exams. Temporal bone CT scan (Figures 1 and 2) revealed enlarged jugular bulb on the left. After 2 years of follow-up, patient's symptoms, physical exam and audiometry and CT scan were unaltered. The patient was told about the diagnosis and she learned that no treatment was required for her affection.

Case 2

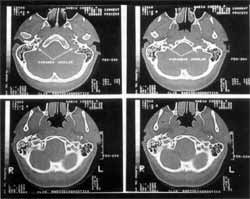

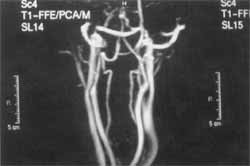

Thirty-nine year-old woman who reported pulsatile tinnitus on the left that lasted for about seven years, synchronized with the pulse, and temporal-parietal-occipital headache on the same side for two months, plus worsening of tinnitus in the past six months. She reported history of improvement of tinnitus upon digital compression of the lateral region of the neck at the level of the ipsilateral jugular vein and head movement; when flexing the head towards the front, the symptoms worsened. She also reported that her father had died of an abdominal artery aneurysm. At the physical exam, she had normal otoscopy and audiometric assessment and dysfunction of temporal-mandibular joint. At the time, a temporal bone CT scan was ordered, evidencing enlarged jugular bulb on the left, but the patient disappeared after the exam. She returned two years and a half later saying that she had worn a dental prosthesis and the headache had improved during the period. However, the tinnitus was present irregularly, once or twice a week, and it worsened with anxiety and head movement. At that time, she could feel it also without moving the head. Nevertheless, she still had experienced improvement as a result of digital compression on the lateral region of the neck at the level of the ipsilateral jugular vein. Otoscopy and audiological assessment were within normal ranges and CT scan did not evidence differences when compared to the first one. Nevertheless, the patient insisted on carrying out new tests. In order to exclude the possibility of vascular abnormalities, we conducted a doppler ultrasound of vertebral and carotid arteries, which was normal. Cervical magnetic angioresonance (Figure 3) with study of carotid arteries showed bilateral incipient atheromatosis. The study of cervical arteries and jugular veins showed normal path, flow and shape, and asymmetry of jugular caliper within the normal variation range. In this exam, we noticed a vascular loop (probably the anterior-inferior cerebellum artery) extending from the left cerebellum-point angle up to the proximal third of the inner auditory canal, close to the facial and vestibular-cochlear nerves (anatomical variation). Digital angiography (Figure 4) of carotids and vertebral-basilar nerves showed an absence of tumor characteristics, vascular malformations or arterial-venous fistulae in the studied territories.

Figure 1. Case 1: Temporal bone CT scan with contrast, coronal section, showing jugular megabulb on the left (arrows).

Figure 2. Case 1: Temporal bone CT scan without contrast, axial section, showing the difference of size of jugular bulbs (arrows).

Figure 3. Case 2: Magnetic cervical angioresonance showing asymmetry of jugular calipers, within normal anatomical range.

Figure 4. Case 2: Carotid and vertebral-basilar digital angiography with no abnormalities, vascular malformation or arteriovenous fistulae.

Four years and a half after the first visit, and two years after the first complete assessment of tinnitus, the patient returned and presented flared symptomatology with normal otoscopy and audiological assessment. A new doppler ultrasound of carotids and vertebral arteries showed normal results. The third temporal bone CT scan showed enlarged left jugular bulb, similar to the result of other exams. The patient was instructed again about the diagnosis and learned that no treatment was required.

Case 3

A 60-year-old male hypertensive and diabetic patient came to a visit to manage a new acute crisis of allergic chronic rhinitis. After 2 months, he reported severe pulsation on the right ear, together with ipsilateral hearing loss. Otoscopy and audiological assessment were normal on the left, mild mixed hearing loss in low frequencies and moderate in middle frequencies and profound sensorineural hearing loss as from the frequencies of 3KHz. Temporal bone CT scan (Figure 5) showed enlarged jugular bulb on the right. The patient was oriented about the diagnosis and reassured.

Figure 5. Case 3: Temporal bone CT scan without contrast - coronal section, showing jugular megabulb on the right (arrows).

Figure 6. Case 4: Videotoscopy showing reddish spot that did not exceed the limits of the upper part of left tympanic membrane, suggesting tympanic glomus tumor.

Case 4

A 53-year-old female patient with complaint of pulsatile tinnitus synchronized with pulse for two years in the left year. For six months, she had experienced worsening of tinnitus and pain. At videoendoscopic exam (Figure 6) she presented a reddish spot on the anterior-inferior quadrant of the left tympanic membrane that did not exceed the limits of the upper half, visualized by transparency. Audiological assessment showed normal hearing on the right and mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss in frequencies 4 and 6HKz on the left. Temporal bone CT scan showed solid nodular lesion measuring 0.7 x 0.3cm on the hypotympanic region, and magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 7) showed a small nodule measuring about 6mm. The patient was submitted to surgical intervention on the left, with excision of tympanic glomus tumor. At histopathological analysis, it was noticed that the lesion was formed by connective tissue with proliferation of capillary lumen recovered by a single layer of flat elongated endothelial cells, with the presence of multiple layers of glomic cells. After the surgery, the patient resolved its symptomatology completely.

DISCUSSION

There are a number of causes of pulsatile tinnitus. The classification of pulsatile tinnitus according to synchrony with pulse offered a useful clinical perspective, in order to define if the etiological hypothesis is vascular or not.

As a general rule, arterial-venous fistulae, arterioarterial anastomosis, intraluminal irregularities of the arterial carotid system, cervical venous hums, elevated cardiac output, cardiac hum, abnormalities of the jugular bulb and elevated intracranial pressure are normally associated with normal otoscopy17.

Vascular neoplasia and intratemporal meningioma may present alterations at otoscopy Patients with pulsatile tinnitus and normal otoscopy require audiological assessment, head and temporal bone CT scan to define an intratemporal lesion17. The most common age range of patients described in the literature with pulsatile tinnitus is 20 to 40 years, predominantly present in female subjects25. Venous hum, in turn, is another term used by the literature to describe pulsatile tinnitus of unknown etiology3,29.

Surgical intervention of symptomatology with cervical venous hum or enlarged jugular bulb has been recommended only in severe symptoms that interfere in patients' daily activities3,29. Some authors suggestedz9 retrograde venography with occlusion of internal jugular vein with Fogarty catheter to perform closure of jugular veins in order to relive the tinnitus. This procedure is not normally recommended except in cases of jugular coming from the middle ear.

Patients with retrotympanic mass should be submitted to temporal bone high-resolution CT for initial assessment. If tympanic glomus tumor, aberrant internal carotid artery or abnormality of jugular bulb were diagnosed, there is no need to conduct other imaging studies26. For patients with jugular glomus tumors, neck CT scan should be conducted to detect possible tumors on the pathway of the carotid arteries22. Carotid angiography is indicated only in possible surgical cases in order to assess the brain collateral circulation (arterial and venous) providing a possibility of vascular ligation and/or embolization of tumor22.

Figure 7. Case 4: Temporal bone MRI showing a nodule measuring 6mm on hypotympanus (circle); a: coronal section, b: axial section.

Current knowledge about pulsatile tinitus suggests that fundoscopy should be conducted in all patients whose evaluation is suggestive of non-vascular aberration as the cause of pulsatile tinnitus17.

Vascular neoplasia includes glomus tumor and cavernous hemagioma. The most common symptom of glomus tumor is conductive hearing loss and unilateral pulsatile tinnitus27.

There is some resistance to performing arteriographic assessment of patients with pulsatile tinnitus because of the inherent risks of the test. But, unless an arteriography is performed, possibly fatal diseases that are treatable, such as arterial-venous fistula and aneurysm would not be diagnosed17.

Neuro-ophthalmological exam should be part of the patient's evaluation if history and physical exam are suggestive of neuro-otological pathologies. In such cases, fundoscopy is important to detect papilledema and visual acuity. After clinical evaluation, diagnosis of pulsatile tinnitus may be confirmed by the rational use of magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic angioresonance, CT scan of temporal bone and carotid doppler ultrasound. Angiography should be performed only in selected cases26.

CONCLUSION

The authors reemphasized in the present study that audiological assessment of pulsatile tinnitus, in which normally there are not otoscopic and audiometric alterations, should be further investigated once in most cases it is possible to come up with an etiological diagnosis. If on the one hand there is not a lot to be done as to clinical and surgical management of alterations such as jugular megabulb, on the other hand diagnostic elucidation is important for the sake of the patient. The knowledge helps us assure the patient that despite the presence of vascular alterations, there will be no complications or hemorrhages, even in the presence of symptoms. In other situations, the diagnosis of surgically treatable affections, such as tympanic or jugular glomus tumor, results not only in resolution of the case but also prevention of severe intracranial complications.

REFERENCES

1. BUCKWALTER, J. A.; SASAKI, C. T.; VIRAPONGSE, C. Pulsatile Tinnitus Arising From Jugular Megabulb Deformity: A Treatment Rationale. Laryngoscope, 93: 1534-9, 1983.

2. CAMBELL, J. B.; SIMONS, R. M. - Brachiocephalic Artery Stenosis Presenting With Objective Tinnitus J Laryngol Otol, 101: 718-20, 1987.

3. CHANDLER, J. R. - Diagnosis and Cure of Venous Hum Tinnitus. Laryngoscope, 93: 892-5, 1983.

4. COCHRAN, J. H.; KOSINICKI, P W - Tinnitus as a Presenting Symptom in Pernicious Anemia. Ann. Otol. Rhinol Laryngol, 88: 297, 1979.

5. CUTFORTH, R.; WEISMAN,. J.; SUTHERLAND, R. D. - The Genesis of the Cervical Venous Hum. Am. Heart J., 80: 48892, 1970.

6. DONALD, J. J.; RAPHAEL, M. J. -Pulsatile Tinnitus Relieved by Angioplasty. Clin Radiol, 43: 132-4, 1991.

7. FERNANDEZ, A. O. - Objective Tinnitus: A Case Report. Am. J. Otol., 4: 312-4, 1983.

8. FORTE, V; TURNER, A.; LIV P - Objective Tinnitus Associated With Abnormal Emissary Vein. Otolaryngology, 18: 232-5, 1989.

9. Gibson, R. Tinnitus in Paget's Disease with External Carotid Ligation. J. Laryngol. Otol., 87: 299-301, 1973.

10. GLASSCOCK, M. E. III; DICKINS, J. R. E.; JACKSON, C. G. - Vascular Anomalies of the Middle Ear. Laryngoscope, 90: 77-88, 1980.

11. GRUBER, B.; HEMMATI, M. - Fibromuscular Dysplasia of the Vertebral Artery: An Unusual Cause of Pulsatile Tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 105: 113-4, 1991.

12. GULYA, A. J.; SCHUKNECHT, H. F. - Letter to the Editor. Am. J. Otol., 5: 262, 1984.

13. HARDISON, J. E., SMITH, R. B., CRAWLEY, I. S. - Self-Heard Venous Hums., JAMA, 245: 1146-7,1981.

14. IGLAUER, S. - Objective Tinnitus Aurium: Four Cases. Arch. Otolaryngol., 18: 145-51, 1933.

15. LESINSKI, S. G., CHAMBERS, A. A., KOMRAY, R. - Why Not the Eighth Nerve Neurovascular Compression: Probable Cause for Pulsatile Tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 87: 89-94, 1979.

16. LEVEQUE, H., BIALOSTOZKY, F., BLANCHARD, C. L. Tympanometry in the Evaluation of Vascular Lesions of the Middle Ear and Tinnitus of Vascular Origin. LARYNGOSCOPE, 89: 1197-218, 1979.

17. LEVINE, S. B.; SNOW JR, J. B. - Pulsatile tinnitus. Laryngoscope, 97: 401-6, 1987.

18. NISHIKAWA, M.; HANDON, H.; HIRAI, O. - Intolerable Pulse-Synchronous Tinnitus Caused by Occlusion of the Contralateral Common. Carotid Artery. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 101: 80-3, 1989.

19. OVERTON, S. B.; RITTER, F. N. - A High Placed Jugular Bulb in the Middle Ear. A Clinical and Temporal Bone Study. Laryngoscope, 83: 1986-91, 1973.

20. PENSAK, M. L. - Skull Base Surgery. In: M.E. Glasscock and G.E. Shambaugh (Eds.) Surgery of the Ear. W B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia. 1990, 503.

21. PULEC, J.L. - Abnormally Patent Eustachian Tubes: Treatment With Injection of Polytetratlouroethylene (Teflon) Paste. Laryngoscope, 77: 1543-1554, 1967.

22. REMLY, K. B.; COIT, W E.; HARRISBERGER, H. R. Pulsatile Tinnitus and the Vascular Tympanic Membrane: CT, MRI, and Angiographic Findings. Radiology, 174: 3839, 1990.

23. SAEED, S. R.; HINTON, A. E.; RANSDEN, R. T. Spontaneous Dissection of the Intrapetrous Internal Carotid Artery. J Laryngol Otol, 104: 491-3, 1990.

24. SILA, C.A., FURLAN, A.J. AND LITTLE, J.R. - Pulsatile Tinnitus. Stroke, 18: 252-6, 1987.

25. SISMANIS, A. - Otologic Manifestations of Benign Intracranial Hypertension Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management. Laryngoscope, 97: 1-17, Suppl. 42, 1987.

26. SISMANIS, A. & SMOKER, W R. K. - Pulsatile tinnitus: receW advances in diagnosis. Laryngoscope, 104: 681-8, 1994.

27. SPECTOR, G. J.; CIRALSKY, R. H.; OGURA J. H. - Glomus Tumors in the Head and Neck. III. Analysis of Clinical Manifestations. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 84: 73-9,1975. 28. SUBOTIC, R. - The High Position of the Jugular Bulb. Acta Otolaryngol., 87: 340-4,1979.

29. WARD, P H.; BABIN, R.; CALCATERRA, T C. - Operative Treatment of Surgical Lesions with Objective Tinnitus.Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 84: 473-82,1975.

* Auxiliary Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Universidade do Amazonas, Master studies in Otorhinolaryngolcgy under course at FCM da Santa Casa de São Paulo.

** Master studies in Otorhinolaryngology under course at Inter-Institutional Partnership Universidade do Amazonas and UNIFESP

*** Joint Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Universidade do Amazonas, Master studies in Otorhinolaryngologyunder course at Inter-Institutional Partnership Universidade do Amazonas and UNIFESE

Study conducted at Clrnica Otorrinos Associados - Manaus /AM.

Address for correspondence: Eduardo Abram Kauffman - Rua João Valerio, 66 - São Geraldo - 69053-140 Manaus /AM.

Tel/Fax: (55 92) 234-1818 - E-mail: eduardokaullman@uol.com.br

Article submitted on July 4, 2000. Article accepted on September 14, 2000.