Year: 2001 Vol. 67 Ed. 1 - (20º)

Relato de Casos

Pages: 123 to 126

Nasal Septum Schwannomas - Cases Report and Review, of the Literature.

Author(s):

Carlos K. Takara*,

Lídio Granato**,

Edson Taciro*,

Oswaldo A. B. Rios***,

Veridiana S. B. Brasileiro****,

Mariana Bianco*****.

Keywords: nasal septum, schwannoma, and neurinoma

Abstract:

Benign schwannomas are common tumors that arise from the neural sheath of peripheral, autonomic, and cranial nerves. Between 25% e 45% of all such lesions occur in the region of the head and neck, but in nose and paranasal sinus are rare. Schwannomas of nasal septum are really rare lesions. Because schwannomas are radio resistant, complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Paranasal sinus schwannomas have a rich vascular supply, are generally slow growing, and may achieve large size with multiple sinus involvement before detection. The authors presented two cases of nasal septum schwannomas and reviewed the literature concerning diagnosis and management.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses schwannomas are rare¹. They do not have preference for gender, age or race, although they are more common in patients aged older than

20 years.

Evolution is long and symptomatology is non-specific, and there may be obstruction or nasal bleeding. Diagnostic confirmation is done by means of anatomic pathologic analysis after surgical excision or biopsy.

Due to its rare occurrence and because they are the only septal cases treated using functional endoscopic sinusal surgery, the authors decided to report them, conducting a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

Case I

A.M. S, female 52-year-old Caucasian patient, from Bahia, complained of right progressive nasal obstruction for one year, aggravated in the previous 6 months, presenting occasional bleeding and mouth breathing.

She reported tonsillectomy performed 22 years before.

At otoscopy, she presented secretory otitis media on the right ear. In the right nasal cavity we saw a mass of 2.5 cm in diameter, smooth, reddish, with hardened surface that was painful and bled easily (Figure 1).

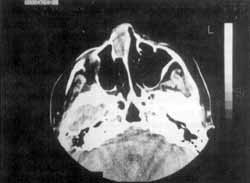

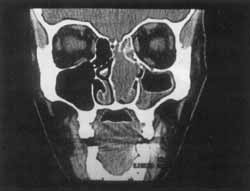

CT scan showed an image with density of soft parts that occupied the whole nasal cavity, with expansive characteristics and no lytic alterations (Figures 2 and 3).

Case 2

M. E. N. N. B., a female 45-year-old Caucasian patient, from Serra Pelada /MG, psychologist.

The patient referred nasal bleeding for 2 months on the left nasal fossa.

At ENT exam, we observed a smooth, shinny, hypervascularized mass on the left nasal fossa, which had characteristics of polyp and that extended from the region of the middle turbinate to the superior one and was implanted in the nasal septum on the

middle-superior portion. It partially recovered the inferior concha.

CT scan, similarly to the other case, showed the same characteristics of expansive lesion, without bone alterations. However, it was slightly larger (3.0 x 1.0) and blocked the ostiomeatal region determining retention of thick material inside the left maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses (Figure 4 and 5).

In both cases, the injection of paramagnetic contrast did not show areas of anomalous highlight.

Figure 1. Endoscopic view of septal schwannoma that occupied the whole anterior portion of the right nasal cavity, right after the region of vestibule.

Figure 2. CT scan at axial section of the paranasal sinuses showing a tumor of precise round limits and soft consistency, without bone lesions, occupying the right nasal fossa and originated from the nasal septum.

We decided to carry out surgical treatment using nasal endoscopic approach in both cases. Intra-operatively, the masses were bleeding and difficult to excise. We made vertical incisions and detachment of septal mucosa, in order to remove the lesion en bloc, since it was tightly adhered to the septal mucosa in both cases. In order to facilitate removal, we injected in the tumor hydrogen peroxide at 10 volumes (3.5%) with fine needle. The mass became ischemic and reduced bleedingh sienificantly.

Figure 3. CT scan at coronal section of the paranasal sinuses showing a tumor of precise limits that occupied the anterior region of nasal cavity, without bone destruction.

Figure 4. CT scan at sagittal section showing the presence of well defined mass fixed on the nasal septum and occupying the medial superior portion of left nasal fossa (3.0x1.0).

The removal of the lesion together with the septal mucosa resulted in a nude area of mucoperiosteum of 2 cm in diameter in the first case and of 3 cm in the second. We conducted cauterization of the remaining margins of septal mucosa and conventional packing of right and left nasal cavity, respectively.

Post-operative period was uneventful and anatomic pathological analyses revealed nasal mucosa schwannomas.

DISCUSSION

Involvement of nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in schwannomas is very rare. There is no preference for age, gender or race, but it is more common after 20 years of age. Head and neck region is affected in 20% to 45% of the cases (Ross et al., 1988). The most affected paranasal sinuses in decreasing order are ethmoidal, maxillary, sphenoidal and frontal. The area the least affected in the nasal cavity is the nasal septum (Shugar et al., 1981). Until 1993 only 11 cases of nasal septum schwannomas had been described (Oi et al., 1993) and none of them were treated with endoscopic surgery.

Schwannomas were described for the first time by Verocay, in 1908, and they derive from Schwann cells from the neural crest (Kaufman, 1976).

In the head arid neck region, schwannomas were described in the internal acoustic canal (acoustic nerve is the most affected), pharynx, parapharyngeal space, tongue, soft palate, larynx, external auditory canal and trachea. They are benign and grow slowly; however, they may become malignant (Kaufman, 1976; Supiyaphun et al., 1997).

Schwannomas are vascularized tumors that present bleeding during surgical procedures. They usually show grayish surface and yellow areas. The yellow color, if present, is a pathognomonic sign of schwannomas, due to the presence of mast cells.

Another benign tumor of the Schwann sheath is neurofibroma, relatively well circumscribed, non-encapsulated, frequently found on the skin and subcutaneous cell tissue. The tumors are differentiated by the fact that schwannomas originate from Schwann cells and neurofibrorhas originate from the neurons of the sheath (Hawkins and Luxford, 1980).

Cranial nerves, spinal nerves and autonomic nerves have Schwann cells and may originate a schwannoma (Hawkins and Luxford, 1980). Olfactory and optical nerves are extension of the central nervous system, recovered by glial cells, and therefore, affected by this kind of tumor:

Macroscopic appearance is jelly-like or cystic, and the color is yellowish. It is normally well circumscribed. At microscopy, the main characteristic is the nucleus in palisade and smooth and compact stroma. Compact fibers of stroma, with organized cell areas, are called Antoni type A, whereas smooth fibers of Antoni type B are disorganized cells. It is difficult to define the origin of the tumor in the nasal cavity, but it is believed that it originates from the anterior ethmoidal nerve (innervates the anterior portion of septum), naso palatine nerve (innervates the posterior portion), or autonomic fibers distributed by the septum (Oi et al., 1993).

Figure 5. Coronal section showing the mass occupying almost all left nasal fossa, originated from the septum, and covering the whole superior and middle concha and partially the inferior concha.

There are no characteristic symptoms of schwannomas in the nasal cavity. The history is of a mass that expands throughout the years. Initial complaints are epistaxis and nasal obstruction. Other symptoms include facial edema, mucus purulent rhinorrhea, hyposmia, pain and impairment of cranial nerves.

CT scan is an important radiological study because it enables surgical planning and identification of intracranial and/or intraorbital involvement. Bone preservation is an important finding because it enables differentiation from destructive lesions, such as carcinomas and sarcomas. Schwannomas present increased density inside the lesion, and after application of contrast, there is an increase in the peripheral area because of neovascularization or increased blood supply.

There are few studies of neurogenic tumors using MRI. It is an extremely interesting study because it enables differentiation of soft tissues adjacent to the tumor, but it does not provide information about bone affection. Therefore, CT scarf is the best complementary study in this investigation.

As differential diagnosis, we should consider pleomorphic adenoma, mesenchymal tumors such as sarcomas, as well as low-malignancy carcinomas.

Despite being benign, there may be unfavorable evo-10 lution, depending on the root of cranial or spinal nerves. The treatment of the solitary tumor is surgical and prognosis is excellent.

Classic surgical approach of nasal schwannomas is nasal rhinotomy, offering good exposure for complete excision. In the present cases, we used endoscopic nasal approach, which had not been reported before.

After location of tumor insertion, we removed it with an incision of the septal mucosa and detached it from the septum, removing the tumor in bloc in both cases.

Endonasal approach, despite the difficulty, wasp safe and effective, avoiding external approach. The main advantage of this access is low morbidity, preventing facial scaring that may produce non-esthetical effects.

Other access for benign nasal tumors is medial-facial degloving; although it is a good approach, surgical time is much longer and elaborate.

REFERENCES

1. HAWKINS, D. B.; LUXFORD, W. M. - Schwannomas of the head and neck in children. Laryngoscope, 90 (12): 192-16, 1980.

2. KAUFMAN, S. M.; CONRAD, L. P. - Schwannoma presenting as a nasal polyp. Laryngoscope, 595-7, 1976.

3. OI, H.; WATANABE, Y.; SHOJAKU, H.; MIZUKOSHI, K. Nasal septum neurinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. (Stockh) 504 (suppl): 151-4, 1993.

4. ROSS, C.; WRIGHT, E.; MOSELEY, J; REES, R. - Massive schwannoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses. South Med. J., 81 (12): 1588-91, 1988.

5. SHUGAR, J. M. A.; SOM, P. M.; BILLER, H. F. - Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the paranasal sinuses. Head Neck Surg., 4: 72-6, 1981.

6. SUPIYAPHUN, P.; SNIDVONGS, K.; SHUANGSHOTI, S.; KHOWPRASERT, C. - Malignant transformation in a benign encapsulated schwannoma of retropharyngeal space: a case report. J. Med. Assoc. Thai, 80 (8): 540-6, 1997.

* Doctorate studies under course at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo.

** Joint Professor of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo and Head of the Clinic at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital de Misericórdia da Santa Casa de São Paulo.

*** Graduate of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo.

**** Resident Physician of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo.

***** Resident Physician of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa de São Paulo.

Address for correspondence: Departamento de Otorrinolaringologia - São Paulo.

Rua Dr. Cesário Motta Jr., 112 - Vila Buarque - 01277-900 São Paulo /SP.

Article submitted on July 4, 2000. Article accepted on August 10, 2000.