Year: 2000 Vol. 66 Ed. 5 - (6º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 458 to 465

Reconstruction of the Larynx Using Sternohyoid Muscle.

Author(s):

Robert Thomé*,

Daniela C. Thomé**,

Rodrigo A. C. Cortina**,

Hélio Kawakami***.

Keywords: larynx, laryngeal surgery, laryngeal reconstruction, sternohyoid muscle

Abstract:

Aim: To discuss the surgical planning, the influence of different surgical technique variables in the results and the complications of using the sternohyoid muscle as a flap on reconstruction of the larynx. Material and methods: Sixty - seven patients with glottic or transglottic tumors in a 29 year period (group 1) and three patients with cicatricial laryngotracheal stenosis in the past five years (group 2) had varying vertical partial resection and a bipedicled or pedicled superiorly sternohyoid muscle flap reconstruction. Results: Group 1: the flap restored the anatomy of the larynx and the muscle bulk contributed for an adequate glottic closure in 88% of the patients; group 2: the flap provided one-stage dynamic luminal support and epithelial resurfacing of the laryngotracheal segment. Conclusion: The use of the sternohyoid muscle as a flap demonstrated to be a safe, versatile, with consistent results on reconstruction of the larynx.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Laryngeal reconstructive surgery has gone through major breakthroughs in the last 30 years and has generated new surgical proposals, in order to compensate the tissue deficit originated from the resection of tumors or fibrous tissue, aiming at obtaining better functional and more consistent results. The variability of surgical techniques, the majority using flaps from nearby tissues, shows how difficult laryngeal reconstruction is, in addition to proving that there is no consensus among surgeons as to the preferred surgical technique.

At the moment, the concerns of the surgeon should not be focused only on where to resect, but rather on how to repair the larynx, in an attempt to minimize anatomical distortions by choosing different surgical techniques and their variations.

Laryngeal reconstructive surgery includes a large number of surgical procedures that combine two factors: resection of fibrous tissue responsible for cicatricial stenosis or the tumor (based on the knowledge of tumor propagation and laryngeal compartments) and repair of surgical defect by a specialist that knows the anatomy and respects the basic principles of reconstruction plastic surgery. Among these techniques, the use of sternohyoid muscle flap has seemed to be appropriate: first, its vascular richness guarantees safety to the production of the flap; in addition, its accessibility and texture, similar to the reconstructed area, are also positive. Regardless of being a mono or bipedicle flap, the muscle may be positioned on the larynx without tension. The first reference to this surgical technique in the literature is the study of Pressman17, who described the technique of partial laryngectomy, preserving arytenoid cartilage and using infrahyoid muscles for repair: one or both laminae of thyroid cartilage were resected to help approach the tumor and later they were repositioned in a site created between the infrahyoid muscles, so that sternohyoid/ thyrohyoid muscle flap was kept in medial position and recovered by external thyroid perichondrium.

Bailey3 modified the procedure described by Pressman17, developing a bipedicle flap of sternohyoid muscle and external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage for post-vertical partial laryngectomy tissue replacement and positioning the flap inside thyroid lamina. Bailey4, in a experimental study in 50 dogs, demonstrated the survival of the muscle with different levels of fibrosis.

Bailey and Calcaterra5 and Bailey6 presented good results obtained from bipedicle flaps in 31 and 70 patients, respectively. Bernstein and Holt7 conducted an experimental study in dogs introducing a bipedicle sternohyoid flap between the lamina of thyroid cartilage and internal perichondrium in order to medialize a paralytic vocal fold; a histological study demonstrated the survival of flaps. Maran et al.14 conducted an experimental study in dogs comparing the results of hemilaryn gectomy with resection of thyroid lamina through the rotation of piriform sinus mucosa flap, or using bipedicle flaps of sternohyoid, thyrohyoid and sternohyoid muscles stabilized in the endolarynx by the external perichondrium - without resection of thyroid lamina and bipedicle muscle flap recovered by thyroid external perichondrium. These authors studied glottic closure using two parameters: subglottic pressure and fundamental frequency and they concluded that the volume provided by the muscle is important in subglottic pressure and voice production, and the best results in glottic closure were obtained when the surgical technique preserved the thyroid lamina.

Ogura a Biller16 reported the use of sternohyoid muscle flap, from inferior pedicle, recovered with flap of aryepiglottic fold, to reconstruct glottic region if frontolateral laryngectomy included the whole arytenoid cartilage.

Hirano12 proposed a muscle flap with superior pedicle to repair the defect resultant from a vertical partial laryngectomy with resection of the whole lamina of thyroid and arytenoid cartilages. The muscle was recovered with piriform sinus mucosa flap or graft of lip mucosa. Hirano13 uses skin inlets from the neck as endolaryngeal lining. Calcaterra" stated that the inferipr pedicle flap described by Ogura and Biller16 tended to loosen from the posterior commissure and predisposed to aspiration, because of the rotation of aryepiglottic mucosa fold. The author described myofascial flap of sternohyoid muscle with superior pedicle, without making such an acute angle with the flap, such as in Hirano12 technique, to repair the defect of resecting the vocal fold and arytenoid cartilage. Eliachar et al.10 created the bipedicle myocutaneous flap with skin inlets over sternohyoid muscle (rotary door flap) to reconstruct a laryngotracheal deficit resulting from resection of tumor or fibrous tissue. Burgess8 conducted another experimental study in dogs performing vertical partial laryngectomy with arytenoidectomy reconstructing with sternohyoid muscle without graft or with mucosa or perichondrium graft. The author obtained patent larynxes in 100% of the dogs, repairing of arytenoid site with superior pedicle flap in 78% and 22% with bipedicle flap. This last group did not show reduction of volume, whereas the first group showed a 23% reduction when compared to the contralateral muscle used as control (also denervated). No macroscopic changes were observed and histological study showed non-keratinized stratified scamous epithelium, without differences in cellular layer thickness regardless of graft.

Andrews et a1.2 conducted an experimental study in dogs comparing acoustic and aerodynamic analysis of vocal function in four types of repairing surgical techniques: in dogs with sternohyoid flap with superior pedicle, videolaryngoscopy showed appropriate lumen at glottic level. They observed that the muscle flap suffered atrophy and migration of posterior cricoid wall, with posterior glottic chink, affecting subglottic pressure and acoustic and aerodynamic lab analyses. Netterville et al.15 expanded the indications of use of sternohyoid muscle flaps when they applied it to repair tissue deficit resultant from the resection of teflon granuloma in paraglottic space, with bipedicle flap and inferior pedicle, respectively.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of standard frontolateral laryngectomy and repair with bipedicle myoperichondral flap. A, longitudinal incision of muscle and detachment of external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage; B, sutured perichondrium to the medial surface of the muscle; C, flap transplanted to the receptor area, perichondrium facing the. lumen; D, position of muscle in relation to thyroid lamina; E, closure of thyrotomy.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of enlarged frontolateral laryngectomy and reconstruction with muscle flap of superior pedicle, recovered with graft of jugal mucosa. A, section of muscle perpendicular to its longitudinal axis (arrow); B, flap rotated 90° towards the larynx; C, flap immobilized by suture on the receptor area and thyrohyoid muscle at straight angle. EH - sternohyoid muscle, ET - sternothyroid muscle, P - external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage.

The present study presents the results obtained in 67 patients with glottic and transglottic tumors and 3 patients with laryngotracheal cicatricial stenosis who were submitted to partial vertical resection of different extensions and repairing conducted with sternohyoid muscle, such as bipedicle myoperichondrium or myocutaneous flap and myomucous flap with inferior pedicle.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Group 1. Since 1969, 67 patients with glottic or transglottic tumors were submitted to reconstruction with sternohyoid muscle flap after standard and enlarged frontolateral laryngectomy. Male patients have a prevalence over women of 5:1, average age of 53 years (age variation from 32 to 74 years). Depending on the dimensions of the tumor and the extension of the thyroid cartilage resection, patients underwent mono or bipedicle muscle flap reconstruction.

Tumors were staged according to the criteria of the American joint Committee on Cancer (1992)1. Out of 49 (73%) patients with T1b or T2 glottic tumors, 44 were submitted to standard frontolateral laryngectomy and reconstruction of myoperichondrial flap (sternohyoid muscle recovered with external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage), bipedicle (Figure 1) and 5 patients, who had horseshoe glottic tumor, were submitted to frontal laryngectomy and reconstruction with bipedicle flap recovered with graft of jugal mucosa, used bilaterally. Six of these 49 patients with glottic tumors had been submitted to curative doses of radiotherapy, without results.

Eighteen patients (23%), 10 with glottic tumors T3 and 8 with transglottic tumors (2cm or less in diameter, without fixation of vocal fold or compromise of subglottic region or anterior commissure, or radiological evidence of cartilage invasion) underwent enlarged frontolateral laryngectomy with resection of anterior and middle thirds (height of vocal process of arytenoid cartilage) or the whole lamina of thyroid cartilage on the side of the tumor and 1cm on the opposite side, and reconstruction using flap of superior pedicle, followed by jugal mucosa graft (Figure 2).

Group 2. In the previous 5 years, 3 patients, two children and one adult, with severe laryngotracheal cicatricial stenosis received myocutaneous bipedicle flap (rotary door flap) to repair the loss of anterolateral substance, resulting from resection of cartilage and soft parts responsible for stenosis, in one single surgical time. The flap was rotated 180° in its longitudinal axis, and the skin was directed to the lumen serving as a lining, and muscle mass with vascularization and innervation was preserved as dynamic support (Figure 3).

Surgical technique

The following factors should be considered in the surgical technique: 1. Identify and preserve vascularization and innervation of sternohyoid muscle; 2. Plan a larger muscle flap than existing surgical deficit to compensate or anticipate atrophy of the transplanted muscle at variable extension; 3. Provide stability to the flap, which should lie on the correct anatomical position without tension, the main reason for dehiscence of suture and displacement of flap; 4. Leave no bloody surface in endolarynx to avoid second intention scaring; 5. Separate both halves of larynx by placing a thin plaque or a silastic solid mold in the larynx during healing in order to prevent adherence of corresponding areas on both sides.

Bipedicle myoperichondral flap.

The surgical technique includes standard frontolateral laryngectomy with exeresis of 1cm of thyroid cartilage on both sides and repair with bipedicle myoperichondral flap. The sectioned margin of the contralateral vocal fold was sutured to the external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage aiming at elongating the vocal fold and reducing the formation of fibrotic tissue in the anterior commissure.

External perichondrium of thyroid cartilage on the side of the tumor was displaced and sutured to the medial surface of sternohyoid muscle. A longitudinal incision was made on the junction of posterior and middle thirds of stemohyoid muscle (1.5 to 2cm from medial margin), deepened to interest external perichondrium and prolonged 1.5cm upward and downward in relation to the margin of thyroid cartilage. Bipedicle muscle-perichondrium flap produced in such a fashion was elevated and then transplanted to endolarynx with the perichondrium facing the lumen, through thyrohyoid and cricothyroid membranes, sutured to the margins of the surgical defect.

A thin plaque or a silastic solid mold was placed inside, separating both sides of larynx. The plaque had a T shape and endolaryngeal branch was directed to anterior thyroid angle, until vocal processes of arytenoid cartilages, and perpendicular branch was supported and sutured to pre-laryngeal plans. The mold was made from a block of soft silicone, triangular in its anterior wall to reproduce the anatomy of anterior commissure and allow results to be as anatomical as possible.

The mold was inserted and positioned with the superior extremity at the level of aryepiglottic folds, and the inferior was placed right over the tracheal opening. The mold was kept in the desired position by transfixation of trachea and the mold, through two parallel threads of 2.0 nylon 1cm away one from the other and tied on the anterior wall of trachea with a series of knots that served as a parameter for their removal. Next, the laminae of thyroid cartilage were sutured in position, and the stitch was made below the superior margin involving also the petiole of epiglottis cartilage in order to bring it to its anatomical position.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of resection of laryngotracheal stenosis and repair of myocutaneous flap (rotary door flap). A, limitation of skin inlet on sternohyoid muscle; B and C, flap rotated 180° in its longitudinal axis, suture of skin inlet to laryngotracheal mucosa; D, final aspect.

Myocutaneous flap of superior pedicle.

The surgical technique includes enlarged frontolateral laryngectomy with vertical resection of anterior and middle thirds, or of all thyroid cartilage lamina and of 1crim on the opposite side and repair with muscle flap of superior pedicle. Reconstruction 'started with a suture of the sectioned margin of contralateral vocal fold to the external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage. Muscle stemohyoid on the side of the tumor was detached and sectioned perpendicularly to its longitudinal axis, approximately 5cm below the middle height point of thyroid cartilage. At glottic level, muscle flap was rotated 90° towards the larynx and positioned in order to occupy the whole receptor area.

The flap was sutured in its new position, putting together the distal extremity of the flap to the mucosa and interarytenoid muscle. Sternohyoid muscle was sutured to the straight angle of sternohyoid flap (Figure 2). Total thickness graft of jugal mucosa was removed to recover the flap with a suture for direct frontal connection of the margins of donating area. In this variation of the technique, the molding was done with a piece of silastic fixed by two transtracheal sutures and maintained in position for 8 weeks. The closure of larynx was conducted through suture of external perichondriums of thyroid cartilage on median line, over the mold.

Bipedicle myocntaneons flap (rotary door flap).

The cutaneous portion of the flap was limited by two longitudinal incisions made at the level of the projection of the margins of sternohyoid muscle, separated 2 to 2,5cm one from the other; medially, it was prolonged downwards to go around the cutaneous scar of tracheotomy. The muscle was elevated, preserving vascular pedicles and rotating it 180° in its longitudinal axis for the laryngotracheal defect. The skin facing the lumen recovered the larynx and the superior portion of the trachea and the muscle provided structural support (Figure 3). A silastic solid mold was placed and kept in place for 6 to 8 weeks.

In any of the techniques described, removal of plaque or silastic solid mold was conducted through a small incision on the skin of the original scar; fixation threads were exposed and sectioned and the plaque was removed through this incision and the mold, through direct laryngoscopy.

In the present study, vocal quality was analyzed from a subjective point of view, and based on the opinion of patients and family members, as well as that of the surgeon. In recent years, patients have been submitted to objective and more sophisticated assessment of vocal quality.

RESULTS

Group 1: the flap repaired anatomy, enabling good breathing pattern through the larynx in all patients - in 6% of them after complementary surgery for correction of stenosis. The volume of muscle provided enough surface for the opposed vocal fold to make contact, achieving appropriate glottic closure in 88% of the patients.

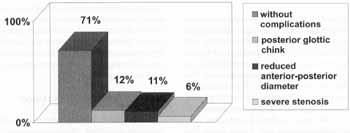

In 12% of the patients, a displacement of the flap to an anterior position took place and caused posterior glottic chink. Aspiration was present mainly in patients whose arytenoid cartilage had been resected - three of them developed aspiration pneumonia. We also observed in 11% of the patients a larynx with reduced anterior-posterior diameter because of anterior fibrous adherence, leading to impact over vocal quality.

The best anatomical repair was obtained with the use of solid mold instead of the thin silastic plaque. Post-operative vocal quality varied according to the extension of surgical resection and degree of success of anatomical repair, and the best results were obtained in patients in which preservation of arytenoid cartilage was possible. The period until decannulation was considered longer in reconstruction with monopedicle flap than with bipedicle flap. Complications were summarized in Graph 1.

Group 2: the flap repaired the laryngotracheal support and recovering layer in one single surgical time.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the use of sternohyoid muscle flap was indicated for the repair of larynx, in an attempt to restore anatomical and functional status of patient, after surgical resection of glottic or subglottic tumor and severe laryngotracheal cicatricial stenosis. Even though reconstruction does not seem to reproduce minor anatomical details, it provides enough bulk to allow a tight glottic closure for control of subglottic pressure, influencing vocal quality. The recovering with perichondrium, or mucosa of bloody area, prevents second intention scaring and scaring retraction.

We do not believe that there is justification for adoption of muscle flap in unilateral paralysis of vocal fold7, because its medialization may be obtained by more conservative methods, such as increased fold bulk by supplementation of tissue with injecting substances (teflon, gelfoam, collagen, autologous fat, fascia) or framework laryngeal surgery (type I thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction). The use of sternohyoid muscle, according to Netterville et al.15, as a inferior pedicle flap for repairing destruction of tissues, resulting from granuloma of teflon in paraglottic space is a promising technique in our opinion.

The use of mono or bipedicle flap in group I was conditioned to extension of resection of thyroid cartilage. It is evident that repairing with bipedicle muscle flap is reserved to glottic tumors without resection of thyroid cartilage, except for 1cm each side, to include thyroid angle in the block of the surgical piece. In addition, the appropriate suture of the flap to laryngeal tissues, integrity of lamina of thyroid cartilage and non-displaced posterior third of sternohyoid muscle contribute to stabilize the bipedicle flap in position3-6,8.

In enlarged frontolateral laryngectomy, in which the thyroid lamina -.in its total extension or in the anterior and middle thirds - is resected in the tumor side, we use a superior pedicle flap planned with enough length to reach the receptor site and there be positioned, without tension. The suture of sternothyroid muscle to the straight angle of sternohyoid muscle confirms stability and contributes to maintaining the muscle bulk at the correct anatomical position. The upper margin of the muscle flap should be located a little below, at the level of the opposite vocal fold, moving towards the caudal portion during phonation13,14.

Graph 1. Percentage of the main complications - group 1.

In the present study, when using myocutaneous flap rotated 180° in its longitudinal axis and indicated restrictedly to more severe cicatricial stenosis, we intended to repair simultaneously the loss of cartilage and soft parts of laryngotracheal segment, without requiring a cartilaginous or bone graft as support. We believe that to achieve this the use of this flap may be considered very positive, since the contraction of the muscle during inspiration prevents collapse of flap and the cutaneous area recovers laryngotracheal segment, avoiding the need for grafts. These factors are the main reasons for our adoption of myocutaneous flap.

Any reconstruction method that applies muscles has the potential of developing complications such as necrosis, dehiscence of suture, detachment and reduction of flap volume - the main factors accounting for failures of this procedure. The rich segment circulation of sternohyoid muscle makes the procedure feasible, added by length, volume and arch of rotation, necessary to reach and correct tissue laryngeal deficits.

Upon planning the dimensions of muscular flap, we should take into account the atrophy that will later lead to reduction of volume at variable degrees; therefore, the flap should be larger than the surgical defect presented by the larynx. Nourishing vessels that penetrate sternohyoid muscle should be carefully and widely dissected, so that the flap reaches larynx without tension.

Superior thyroid artery, the main source, provides to the two superior thirds through sternocleidomastoid, hyoid and direct muscle branches, whereas inferior thyroid and internal thoracic arteries provide to the inferior third. Even though there is not an axial distribution in its vascularization a rich anastomosis network between superior and inferior thyroid arteries is found inside and around the muscle11. Therefore, since it has segmented vascular pedicles, monopedicle flap of sternohyoid muscle may have either a superior or inferior pedicle. The degree of muscle atrophy is smaller when innervation is maintained intact, through the cervical loop (cervical plexus) and its superior root (descending branch of hypoglossus nerve).

In the two variations of the surgical technique, the correct anatomical position of the flap in contact with the receptor site without tension or pull force, is the main factor to reduce the risk of dehiscence of suture. In order to reduce or avoid tension Ogura and Biller16 recommended a horizontal incision relaxing the fascia of the anterior face of the muscle flap.

It is interesting to notice that excessive traction of the suture of bipedicle flap in arytenoid site seems to be the main factor of failure when using this kind of flap, when the arytenoid cartilage is included in one monoblock of surgical piece. Similarly to this muscle, with preserved innervation and vascularization, it has its insertion on the hyoid and stern bones, placed anatomically anterior to the larynx, and its contraction during inspiration pulls the flap to the anterior position, leading to dehiscence of suture and displacement from the correct position, and impairment of the final result of the surgery.

Incomplete posterior glottic closure, present in. our patients, may be caused by the pull of the suture line. Because of this disadvantage, a technical variation that seems to be appropriate in standard frontolateral laryngectomy with resection of arytenoid is the placement of a flap with superior pedicle, introduced by the thyrohyoid membrane in order to fill arytenoid site and prevent pull on the suture when the muscle is contracted. The distal extremity of the flap is sutured to the subglottic mucosa and the posterior margin, to interarytenoid area. The anterior displacement of the bipedicle flap happened

in experimental studies with animals reported by Bernstein and Holt7 and Maran et al.14.

The reconstruction of laryngeal recovering epithelium with external perichondrium of thyroid cartilage or graft of jugal mucosa is important to promote first intention healing and protection against infections. External perichondrium of thyroid cartilage, underlying sternohyoid muscle, recovers endolarynx when the muscle is transplanted to repair a surgical defect. This myoperichondral flap has the advantage of preventing an additional procedure of removal of graft to recover the muscle, what increases morbidity and prolongs surgery time. Mucosa has been used to recover the larynx as flap of ventricular fold, aryepiglottic fold and pirifom sinus or graft of jugal region. The rotation of flap of hypopharynx mucosa produces distortions of the piriform sinus anatomy, resulting in aspiration for a prolonged period of time, delaying decannulation. In myocutaneous flap, rotated 180° in its longitudinal axis, the skin as lining of laryngotracheal segment may result in inelastic recover, forming crusts, growth of hairs and desquamation, characterizing a disadvantage. Hirano et al.12,13 found variable vocal quality that improved when muscle flap was recovered by mucosa. Burgess8 reported that muscle flap may repair glottic competence, but not vibration at phonation. Calcaterral stated that in myofascial flap, the external layer of fascia sutured to the posterior and inferior mucosa along the cricoid and the remaining portion of muscle flap, reconstructs the anterior commissure and guarantees complete recover of defect and quick epithelization. Burgess8 does not consider essential the use of flaps or grafts for recovering of the muscle, provided that the histological final result is not different from that of the muscle without lining, let to heal for second intention as a result of margin retraction.

In Group I, different degrees of laryngeal cicatricial stenosis represented significant problems in the first patients. Since that time, the use of silastic solid mold instead of a thin plaque, improved anatomical results because it maintained corresponding surfaces apart, avoiding adherence between them, reducing the formation of granulation tissue in the suture line and maintaining anatomical configuration of endolarynx, especially of anterior commissure, during the period of healing. Silastic as a material to produce the mold did not cause significant inflammation of tissues and tracheobronchial secretions were not adhered to it. The modification of shape during the surgery has been avoided so that the surface was not rough, causing an additional trauma to the mucosa, more inflammatory response, and formation of granulation tissue. Transtracheal fixation enabled the joint movement of the mold and larynx during breathing, swallowing and cough, avoiding more friction with the mucosa. Moreover, this way of fixing the mold was well tolerated by patients and allowed exchange of tracheal cannula without risk of displacing the mold, enabling better cleaning of tracheotomy.

It seems that the results obtained with the adopted surgical technique may be considered positive. In Group I, muscle flap repaired anatomy, with appropriate glottic closure in 88% of patients and vocal quality that enabled patients to resume professional activities and social life. In Group 2, myocutaneous flap seemed to be an advantage because the repair of laryngotracheal support and recover was obtained in only one surgical time.

CONCLUSION

The use of sternohyoid muscle as a flap has proved to be a very safe procedure, offering easy accessibility, versatility and producing results consisted with a reconstructive laryngeal surgery. The rich segment circulation of the muscle enables the use of bipedicle and superior and inferior pedicles, according to the extension of surgical resection. Preserve segment vascular pedicles of the muscle, make the muscle flap larger than the existing surgical deficit, provide stability to the flap without tension in the correct anatomical position, avoid a bloody surface and use endolaryngeal molding are the factors of the surgical technique that influence the final result and the degree of morbidity.

REFERENCES

1. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott; 1992.

2. ANDREWS, R. J.; CALCATERRA, T. C.; SERCARZ, J. A. et al. Vocal function following vertical hemilaryngectomy: comparison of four reconstruction techniques in canine. Ann Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 106: 261 - 270, 1997.

3. BAILEY, B. J. - Partial laryngectomy and laryngoplasty. A technique and review. Trans Amer Acad Qphtal Otol., 70: 559 - 574, 1966.

4. BAILEY, B. J. - Partial laryngectomy and laryngoplasty. Laryngoscope, 81: 1742 - 1771, 1971.

5. BAILEY, B. J. - Calcaterra T C. Vertical, subtotal laryngectomy and laryngoplasty. Review of experience. Arch Otolaryngol., 93: 232 - 237, 1971.

6. BAILEY, B. J. - Glottic reconstruction after hemilaryngectomy: bipedicle muscle flap laryngoplasty. Laryngoscope, 85: 960 977, 1975.

7. BERNSTEIN, L.; HOLT, G. P. - Correction of vocal cord abduction in unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis by transposition of the sternohyoid muscle. An experimental study in dogs. Laryngoscope, 77: 876 - 885, 1967.

8. BURGESS, L. P. A. - Laryngeal reconstruction following vertical partial laryngectomy. Laryngoscope, 103: 109-132, 1997.

9. CALCATERRA, T. C. - Sternohyoid myofascial flap reconstruction of the larynx for vertical partial laryngectomy. Laryngoscope, 93: 422 - 424, 1983.

10. ELIACHAR, I.; MARCOVICH, A.; HAR SHAI, Y. - Rotary door flap in laryngotracheal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg., 110; 580 - 585, 1984.

11. ELIACHAR, I.; MARCOVICH, A.; HAR SHAI, Y.; LINDENBAUM, E. -Arterial blood supply to the infrahyoid muscles: an anatomical study. Head Neck Surg., T 8 - 14, 1984.

12. HIRANO, M. - Technique for glottic reconstruction following vertical partial laryngectomy. A preliminary report. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 85: 25 - 31, 1976.

13. HIRANO, M; KURITA, S.; MATSUOKA, H. - Vocal function following hemilaryngectomy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 96586 - 589; 1987.

14. MARAN, A. G. D.; HAST, M. H.; LEONARD. I. R. - Reconstructive surgery for improved glottic closure and voice following partial laryngectomy. An experimental study. Laryngoscope, 78: 1916 - 1936, 1968.

15. NETTERVILLE, J. L.; COLEMAN JR, J. R.; CHANG, S. et al. Lateral laryngotomy for the removal of Teflon granuloma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 107- 735 - 744, 1998.

16. OGURA. J. H.; BILLER, H. F. - Glottic reconstruction following extended frontolateral hemilaryngectomy. Laryngoscope, 79-2181 - 2184, 1969.

17., PRESSMAN, J. J. - Cancer of the larynx. Laryngoplasty to avoid laryngectomy. Arch. Otolaryngol., 59:395 - 412, 1954.

18. RUSSEL, J. D.; PERRY, A.; CHEESMAN, A. D. - Cordectomy: a solution to Teflon granuloma of the vocal fold. J. Laryngol. Otol., 109: 53 - 55, 1995.

* Ph.D. Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo.

** Post-Graduate Studies under course at the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo.

*** Plastic Surgeon of Instituto de Cirurgia Plástica Santa Cruz.

Study conducted at the private practice of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery of the authors.

Study presented at I World Congress on Head and Neck Surgery, in Madrid, Spain, November 29 - December 3, 1998; and at CIII Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, September 26 - 29, 1999, in New Orleans, USA.

Address for correspondence: Robert Thomé - Alameda Itú 483 - 01421-000 São Paulo/ SP.

Tel: (55 11) 288-9988 / 570-3260 - Fax: (55 11) 284-3049 - E-mail: rthome@dialdata.com.br

Article submitted on April 10, 2000. Article accepted on April 16, 2000.