Year: 2003 Vol. 69 Ed. 6 - (18º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 846 to 849

Aberrant internal carotid artery in the middle ear

Author(s):

Corintho Viana1,

Fábio Coelho2,

Silvio Caldas Neto3,

Kátia Oliveira4,

Nelson Caldas5

Keywords: middle ear, congenital malformation, aberrant internal carotid artery

Abstract:

Vascular anomalies of the middle ear are uncommon and, because aberrant internal carotid artery, among others, implies great risk at middle ear surgery, it must be remembered at the differential diagnosis. The patient may be asymptomatic, or complains of pulsatile tinnitus and conductive hearing loss. Computer tomography of the temporal bones and magnetic resonance imaging supplemented with magnetic resonance angiography can make the diagnosis. The authors present an aberrant internal carotid artery on a 13-year-old patient, whose diagnosis was performed by otoscopic examination, and imaging methods based on a previous clinical suspicion.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of aberrant internal carotid artery (ICA) in the middle ear space is of approximately 1% in the general population and most of the cases are asymptomatic 1.

This carotid canal abnormality, if not considered, can occasionally lead to mistaken diagnosis of secretory otitis media or middle ear vascular tumor, which can lead to severe surgical accidents.

In most of the cases, patients are symptomatic and present pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss, also added by vertigo, earache, ear fullness and progressive conductive hearing loss in some cases 2.

The differential diagnosis of aberrant ICA in the middle ear should be made with congenital cholesteatoma, tympanic glomus tumor, secretory otitis media, arterial-venous fistula, cavernous sinus fistula, carotid fistula, dehiscence jugular bulb, petrous aneurysm of internal carotid artery, dilation of basilar membrane, persistence of basilar membrane, and abnormality of medium meningeal artery, as demonstrated by the literature 3-5.

CASE REPORT

R.M.G.S.C., 13-year-old female Caucasian patient, referred to our service with history of fluctuating hearing loss and tinnitus on the left for approximately 6 months. Non-pulsatile and whistle-like tinnitus.

ENT examination showed oropharyngoscopy, rhinoscopy, neck examination and otoscopy on the right within the normal ranges. Otoscopy on the left showed normal external ear and intact tympanic membrane, but there was diffuse opacification. During otomicroscopy, the speculum pulsated in the left external ear, following the patient's heartbeat.

Upon inspection, the patient showed multiple erythematous lesions of vascular characteristic on the upper limbs and face. She had been submitted to two surgeries for resection of facial hemangioma, with no other associated disease.

Audiometry revealed conductive hearing loss on the left and normal hearing o the right and type B tympanometry curve on the left with rhythmic pulsing of the device needle.

In order to identify the presence of vascular affection, which would guide the clinical findings to differential diagnosis, we ordered computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bones and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angioresonance.

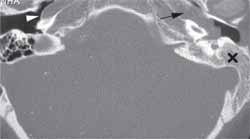

CT scan showed opacification of the left middle ear, in continuity with the intrapetrous carotid canal (Figure 1).

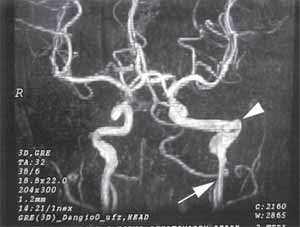

The relevant data of the magnetic angioresonance were: agenesia of the vertical cervical portion of left ICA, with flow through the intra-tympanic anastomoses, carotid-tympanic arteries and inferior tympanic artery, forming an artery that communicates with the horizontal branch of the left internal carotid artery, compatible with aberrant course of the vessel. We could also detect ecstasies of the intra-petrous portion of the artery (Figure 2).

Conservative treatment was adopted, counseling the family about the pathology and warning them about the high risk of a surgical intervention in the ear.

Figure 1. Axial computed tomography of temporal bones on the right side showing normal carotid canal (white arrow). On the left, there is no bone wall, but continuity between the carotid canal (black arrow) and the middle ear. The mastoid on this side is opacified (r), probably owing to obstruction of the pro-tympanum by the aberrant carotid artery.

Figure 2. Angioresonance study showing agenesia of the cervical portion of the ICA, replaced by ascending arterial branches (arrow) which supply the intra-petrous portion of the ectasic artery (top of the arrow).

DISCUSSION

Aberrant courses of petrous vessels are extremely rare 1. In most cases, patients are asymptomatic and if there are symptoms, normally they are pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss.

Intratympanic internal carotid artery is detected especially in women (proportion of 5:1 women-men ratio) and on the right side (2:1 right-left ratio) 2.

The carotid penetrates into the petrous bone via carotid canal, medially to the styloid process, separated from the internal jugular vein just by a carotid sheath. The initial segment of the ICA is vertical and anterior to the cochlea and separated from the middle ear by thin bone layer of 0.5mm thick on average 6.

ICA anomalies of the temporal bone include aneurysms and displacement of the artery, which could occur by congenital or acquired causes. The abnormal course of ICA in the middle ear can be explained embryologically, by malformation of the first and second branchial arches, resulting in persistence of other embryological vascular structures, vessels and anastomosis in the tympanic cavity. Such situation would take to absence of formation of the bone wall that separates ICA from the middle ear 7.

With otoscopy, we can find a red mass seen by transparency in the anterior portion of the middle ear, with pulsatile characteristic or not; audiometry showed conductive hearing loss in the affected ear and tympanometry normally shows pulsatile tympanic membrane 8.

Clinical signs and symptoms, however, cannot differentiate aberrant ICA from other vascular anomalies that can affect the middle ear. Therefore, the diagnosis should be made by complementary radiological exams, such as conventional angiogram, CT scan or MRI with angioresonance.

Temporal bone CT scan defines the vascular organization and the bone structure. Aberrant ICA is defined by the following findings: intratympanic mass, enlarged inferior tympanic canalliculus, absence of vertical segment of ICA and bone coverage of the tympanic portion of the artery 9. CT scan, however, in some cases, cannot differentiate ICA anomaly from very vascularized glomus tumor, since it presents vascular mass with normal bone wall 10.

Conventional angiogram is a very useful method to define ICA abnormalities, vascular supply, to rule out aneurysm and to plan surgical intervention. However, its potential of complications is very high and in general it is avoided in favor of imaging studies. Similar findings can be demonstrated by MRI helping the characterization and definition of the extension of the lesion, using angioresonance, which has less morbidity 1.

The need to treat is controversial in cases clinically and radiologically diagnosed; it can be decided to relieve symptoms or prevent complications, such as ossicle erosion or bleeding. In this type of situation, the best treatment, according to Cohen, 1981, and Hunt, 2000, is to prohibit manipulation of the middle ear and to inform the family about the care the patients should care 11, 12, since the benefits of this type of procedure, in general, do not compensate the anesthetic and surgical risks.

Ruggles and Reed, 1972, recommended separation of the artery from the middle ear space using fascia and bone wax graft 13, which, according to Valvassori and Buckingham, 1974, can predispose to the formation of aneurysm 14. Another method described to separate the ossicles from the ICA is fascia flap or silicone plates, trying to prevent ossicle erosion 8.

However, in the case of an accident with the ICA, treatment can be used to save the patient's life. The initial management should be placement of surgicel packing 7 and cotton in the middle ear and external auditory canal and occlusive dressing, maintained for many weeks to prevent recurrence of bleeding. Other therapy stages to control hemorrhage include posterior nasal packing, surgical ligation of ICA or occlusion of the vessel using a balloon 2, 12, 13.

CLOSING REMARKS

Vascular affections of the middle ear, including aberrant internal carotid artery should always be considered by Otorhinolaryngologist, preventing inappropriate manipulation of the middle ear, which may lead to catastrophic results.

Computed tomography scan and MRI with angioresonance should be used in view of suspicion of aberrant ICA in the tympanic cavity, helping with differential diagnosis of this uncommon pathology.

The treatment, even if necessary in some situations, is controversial. It should be avoided as much as possible considering the risks of procedures and its consequences.

REFERENCES

1. Botma M et al. Aberrant internal carotid artery in the middle-ear space. J Laryngo Otol. 2000; 114: 784-787;

2. Ridder GJ, Fradis M, Schipper J. Aberrant internal carotid artery in the middle ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001; 110(9):892-4.

3. Goldman NC, Singleton GT, Holly EH. Aberrant carotid artery presenting as a mass in the middle ear. Arch Otolaryngol 1971; 94:269-73.

4. Bold EL, Wanamaker HH, Hughes GB et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of vascular anomalies of the middle ear. Laryngoscope 1994;104:1404-11.

5. Tian Q, Linthicum FH Jr. Temporal bone histopathology of aberrant carotid artery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998; 119:506-7.

6. Glasscock ME III, Dickins JR, Jackson CG, Wiet RJ. Vascular anomalies of the middle ear. Laryngoscope 1980; 90:77-88.

7. Sinnreich AI, Parisier SC, Cohen NL, Berreby M. Arterial malformatios of the middle ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1984; 92:194-206.

8. Cole RD, May JS. Aberrant ICA. South Med J 1994; 87:1277-80.

9. Mcelveen JT Jr, Lo WWM, El Gabri TH, Nigri P. Aberrant ICA: classical findings on computed tomography. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986; 94:616-21.

10. Remley KB et al. Pulsatile tinnitus and the vascular tympanic membrane: CT, MRI and radiographic findings. Radiology 1990; 174:33-7.

11. Cohen SR, Briant TD. Anomalous course of the internal carotid artery - a warning. J Otolaryngol 1981; 10:283-6.

12. Hunt JT, Andrews TM. Management of aberrant internal carotid artery injuries in children. Am J Otolaryngol 2000; 21:50-4.

13. Ruggles RL, Reed RC. Treatment of aberrant carotid arteries in the middle ear: a report of two cases. Laryngoscope 1972; 82:1199-205.

14. Valvassori GE, Buckingham RA. Middle ear masses mimicking glomus tumors radiographic and otoscopic recognition. Laryngoscope 1974; 82:119-205.

15. Glasgold AI, Horrigan WD. The internal carotid artery presenting as middle ear tumor. Laryngoscope 1972; 82:2217-21.

1 1 Resident Physician, Service of Otorhinolaryngology, HC - UFPE.

2 Assistant Physician, Service of Otorhinolaryngology HC - UFPE.

3 Joint Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, HC - UFPE

4 Volunteer Physician, Service of Otorhinolaryngology, HC - UFPE.

5 Faculty Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, HC - UFPE.

Service of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Federal University of Pernambuco.

Address correspondence to: Corintho Viana - Av. Eng. Domingos Ferreira, 3181/403 Boa Viagem Recife PE 51020-035

E-mail: corinthoviana@ig.com.br

Study presented as free communication at 36º Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, November 19 - 23, 2002, Florianópolis - SC.

Article submitted on December 12, 2002. Article accepted on August 24, 2003.