Year: 2003 Vol. 69 Ed. 5 - (11º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 657 to 662

Cholesteatoma causing facial paralysis

Author(s):

José Ricardo Gurgel Testa1,

Andy de Oliveira Vicente2,

Carlos E.C. Abreu2,

Simone F.Benbassat2,

Marcos L.Antunes3,

Flávia A. Barros

Keywords: cholesteatoma, facial nerve, facial palsy

Abstract:

Facial paralysis caused by cholesteatoma is uncommon. The portions most frequently involved are horizontal (tympanic) and second genu segments. When cholesteatomas extend over the anterior epitympanic space, the facial nerve is placed in jeopardy in the region of the geniculate ganglion. The aetiology can be related to compression of the nerve followed by impairment of its blood supply or production of neurotoxic substances secreted from either the cholesteatoma matrix or bacteria enclosed in the tumor. Aim: To evaluate the incidence, clinical features and treatment of the facial palsy due cholesteatoma. Study design: Clinical retrospective. Material and Method: Retrospective study of 10 cases of facial paralysis due cholesteatoma selected through a survey of 206 decompressions of the facial nerve due various aetiologies realized in the last 10 years in UNIFESP-EPM. Results: The incidence of facial paralysis due cholesteatoma in this study was 4,85%, with female predominance (60%). The average age of the patients was 39 years. The duration and severity of the facial palsy associated with the extension of lesion were important for the functional recovery of the facial nerve. Conclusion: Early surgical approach is necessary in these cases to improve the nerve function more adequately. When disruption or intense fibrous replacement occurs in the facial nerve, nerve grafting (greater auricular/sural nerves) and/or hypoglossal facial anastomosis may be suggested.

![]()

IntroduCTION

Cholesteatomas are cystic lesions recovered with stratified squamous epithelium filled with build-up of exfoliated keratin located in the middle ear or other pneumatized areas of the temporal bone 1. According to the literature, they can be classified as congenital or acquired. The congenital cholesteatomas represent 2% to 5% of all cholesteatomas, being more prevalent in male subjects (3:1) normally presenting as a whitish tumor located medially to the normal tympanic membrane, especially on the anterior-superior quadrant with no previous history of otorrhea, otological surgery, tympanic membrane perforation or otitis media 2. The etiology remains unknown, but it is believed that the pathogenesis is connected with epithelial migration, reflux of amniotic debris, mucosa metaplasia or embryonic remains. They can also be found in the regions of the petrous apex, cerebropontine angle, jugular foramen, tympanomastoid area and internal and external acoustic canal 2-4.

Acquired cholesteatomas are divided into primary, formed from the retraction of the tympanic membrane resultant from auditory tube dysfunction, or secondary, originated from the epithelial migration through previous perforation of the tympanic membrane 1.

In general, t cholesteatomas have expansive characteristics and bone lysis, which can invade adjacent structures. The mechanism responsible for bone erosion is still controversial and some hypotheses have been advocated such as mechanical compression, osteoclastic stimulation, cytokine action and production of proteolytic enzymes such as collagenase 1, 5-7.

Owing to the destructive and many times insidious behavior of the cholesteatoma, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment help the prevention of complications, which can be very severe.

One of the most important and disabling complications is undoubtedly peripheral facial paralysis, in many occasions responsible for irreversible sequelae, resulting in significant deficit of the patient's quality of life.

Peripheral facial paralysis caused by cholesteatomatous lesion has low incidence and involvement of the facial nerve depends on how the propagation is adopted by the cholesteatoma 1. In acquired cholesteatoma (98% of cholesteatoma), the tympanic segment and the region of the second knee are more affected. In cases in which the disease invades the anterior epitympanic space, the geniculate ganglion is more prone to suffering injuries 8. Congenital cholesteatoma can also cause nerve lesion and the affected segment will depend on the location of the tumor in the temporal bone 9.

The advent of high resolution computed tomography and magnetic resonance has allowed more detailed study of the extension and propagation of the cholesteatoma lesion and its possible complications 10.

The purpose of the present study was to present incidence, clinical characteristics, diagnostic methods, therapeutic approach and evolution of patients with peripheral facial paralysis resultant from cholesteatomatous lesions.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The authors conducted a retrospective study of the cases of peripheral facial palsy owing to cholesteatomatous lesion by assessing the medical charts of 206 patients submitted to facial nerve decompression surgery (from different etiologies) in the period of January 1993 to January 2002, performed at Hospital Sao Paulo, UNIFESP-EPM.

The patients with facial paralysis caused by cholesteatoma were assessed according to the following data: incidence, gender, age, affected side, preoperative duration and degree of paralysis (House-Brackmann), symptomatology and/or associated complications of cholesteatoma, surgical technique, segment of the affected facial nerve, and postoperative functional outcome (paralysis evolution) (Chart 1).Chart 1. Summary of the cases and their main aspects.

Results

In our study, we found 10 cases of peripheral facial paralysis caused by cholesteatoma out of 206 surgeries of facial nerve decompression (for many causes), totaling an incidence of 4.85%. The age of patients ranged from 13 to 65 years, mean age of 39 years. Six patients (60%) were female and seven patients (70%) presented facial palsy on the right.

The duration of paralysis ranged from 7 days to 8 years, being that in 6 patients (60%) the paralysis time was below 2 weeks, two patients (20%) had paralysis for less than 4 months and the others (2 patients) had paralysis for over 2 years.

As to grade of initial facial paralysis (preoperative), 4 patients (40%) had facial paralysis grade V, 3 (30%) had paralysis grade IV, and 3 patients (30%) had paralysis grade VI.

All patients had associated hearing loss on the affected side, 6 of them (60%) presented mixed hearing loss (ranging from moderate to severe) and 4 patients (40%) had anacusis. One patient reported loud tinnitus on the affected ear. One patient presented retroauricular abscess on the affected side (secondary to mastoiditis owing to cholesteatoma) and also meningitis.

All patients were submitted to mastoidectomy (canal wall down) followed by facial nerve decompression (without opening the sheath). The facial nerve impairment by the cholesteatoma was in most time multisegmented, being that the tympanic portion of the facial nerve was the most affected one (6 patients - 60%), followed by the region of the 2nd knee (5 patients). The geniculate ganglion was damaged in 2 patients - 20% and the mastoid segment in only one case (10%). Facial nerve rupture was observed in 1 patient. He had been submitted to previous surgery for removal of the cholesteatoma and facial nerve decompression, presenting partial improvement of facial palsy (grade IV). One year after the surgery he presented worsening of the case (paralysis grade VI) and surgical reintervention was required - there was recurrence of the cholesteatoma together with rupture of the facial nerve at the 2nd knee region, probably owing to the cholesteatomatous lesion.

Tow patients (20%) required placement of greater auricular nerve graft (one of them owing to facial nerve rupture by the cholesteatoma and the other because he still maintained the same grade of paralysis 8 months after decompression) and one patient (10%) was submitted to hypoglossal-facial anastomosis (owing to unaltered paralysis grade, 1 year after decompression). An esthetical surgery was conducted (face lifting) in 1 patient (10%), exactly the one that had had it for the longest time (8 years).

As to functional outcomes after surgical procedure, 6 patients (60%) progressed to grade II facial paralysis 6 months after the surgery (2 of them received greater auricular nerve graft). One patient (10%) progressed to grade III paralysis (after having been submitted to hypoglossal-facial anastomosis). Two patients (20%) presented total recovery of paralysis (grade I) 3 months after the removal of the cholesteatoma and facial decompression nerve performance. In the patient submitted to facial lifting surgery the functional outcome remained the same (grade V paralysis).

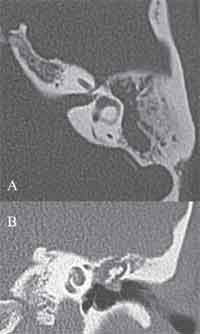

Figure 1. A: Temporal bone computed tomography, axial section evidencing mastoid sclerosis and occupation of antrum, aditus and attic (close to the first knee of the facial nerve) by soft part content material. Note the widening of the cavity together with regularization of the walls, suggesting osteolythic activity (cholesteatomatous lesion).

B: Temporal bone computed tomography, coronal section, demonstrating the occupation of the attical region with soft part material (cholesteatoma), causing lateralization of the ossicular chain. Note the dehiscence of the Fallopian canal in the tympanic portion.

Figure 2. Temporal bone CT scan, coronal section, evidencing cholesteatoma in the attic region with probable impairment of the facial nerve in the tympanic portion.

Figure 3. Temporal bone CT, axial section, showing a giant cholesteatoma that causes extensive bone destruction in the mastoid and epitympanic regions, eroding the whole bone plate of the posterior fossa. Note dehiscence of the Fallopian canal in the region of the geniculate ganglion and tympanic segment.

Discussion

Cholesteatomas are characterized by the abnormal proliferation of cells resulting in accumulation of keratin and destruction of the adjacent bone framework and it can invade and impair the main structures, such as the inner ear, facial nerve and central nervous system.

There is controversy in the literature about the etiopathogenesis of bone reabsorption in cholesteatomatous lesion. The most accepted theory is that of osteolysis induced by mechanical compression of the tumor 9. Some authors believe that the stratified squamous epithelium per se would not be able to erode the bone, requiring the need of concomitant granulation inflammatory tissue for this fact to happen 1, 4. The osteoclastic stimulation of the tumor is also suggested and in a study conducted by Abramson (1969) it was demonstrated that the collagenolytic activity of the cholesteatoma (through collagenase production) is responsible for bone lyses 9.

Peripheral facial paralysis resulting from the cholesteatomatous disease has low incidence, of approximately 1.1% 1 and it probably occurs owing to the compressive effects of the tumor and consequent reduction of blood supply in the facial nerve, as well as by the action of neurotoxic substances produced by the cholesteatoma matrix or the bacterial normally present in the cholesteatomatous mass 1, 8, 11. It is important to point out that in medially invasive cholesteatoma (involving petrous apex, supralabyrinthine region and internal acoustic canal), the likelihood of a dysfunction of the facial nerve increases, and it may reach an incidence of 20% 11, 12.

In case of patients with chronic otitis media that suddenly present peripheral facial paralysis, we should consider the likelihood of concomitant cholesteatomatous lesion 13. In some occasions, the first symptom associated with facial nerve compression by cholesteatoma is its hyperfunction, characterized by fasciculation and hemifacial spasms. In our study we conducted a survey of facial nerve decompression performed in the past 10 years, amounting to 206 decompressions by different causes, being that the most common one was Bell's palsy. Cholesteatoma was responsible for the facial nerve affection in 10 cases (described in the study), amounting to an incidence of 4.85% of decompressions, which confirms the literature reports that peripheral facial paralysis resultant from cholesteatomatous lesion is not frequent.

The involvement of the facial nerve in acquired cholesteatoma is more frequent in the tympanic portion and the region of the second knee 8. Such sites are more affected because they are close to the main dissemination route of the cholesteatomatous lesion, the posterior epitympanic route, which follows the route: Prussak space - posterior epitympanum - aditus - mastoid antrum 8. In six out of ten cases studied, we observed nerve damage preferably in the tympanic portion. The region of the second knee was affected in 5 patients, the geniculate ganglion in two, and the mastoid segment in only one patient.

In cases in which the disease invades the anterior epitympanic space, there is normally more medial propagation of the lesion (especially through supralabyrinthine route) and in such conditions the geniculate ganglion is more susceptible to the noxious action of the cholesteatoma 8. In two cases there was extension of the cholesteatoma to the anterior epitympanic region, with facial nerve compression up to the region of the geniculate ganglion. What calls our attention is that they were probably congenital cholesteatomas, which could have had very aggressive behavior.

Congenital cholesteatoma can also be responsible for facial palsy, especially when located in the petrous apex 9.

In cases of progressive facial paralysis associated with stable conductive hearing loss with no history of chronic otitis media, the hypothesis of congenital cholesteatoma should be considered 13 and the imaging study (computed tomography and magnetic resonance) is essential in the diagnostic investigation, including the differentiation with other pathologies such as cholesterol granuloma (apex) and facial nerve Schwannoma.

Even though cholesteatoma has a more aggressive behavior in the pediatric population, the rate of complications such as facial paralysis is higher in adults, probably owing to the longer progression of the disease 14. Most of our patients came to us right after the onset of facial paralysis, but in one patient there was a long interval between the onset of paralysis and the first visit, which worsened the prognosis.

Even though high resolution computed tomography is the imaging test of choice to assess middle ear and mastoid cholesteatoma, the involvement of the facial nerve in such cases is better evidenced through magnetic resonance, especially in weighted images in T1 after the administration of gadolinium paramagnetic contrast, which leads to impregnation of the contrast in the nerve 4.

Ylikoski (1990) conducted a histopathologic study of the facial nerve in patients with facial paralysis associated with cholesteatoma, submitted to reinnervation surgery and evidenced that some areas of the nerve had extensive fibrotic tissue with absence of axons and Schwann cells15.

Facial nerve rupture in patients with recurrent cholesteatomatous disease was described by Waddell & Maw (2000)5. A similar situation occurred in one of our patients, who was submitted to greater auricular nerve graft placement.

In the differential diagnosis of lesions that can involve intra-petrous facial nerve we can include cholesteatoma (congenital and acquired), otitis media tuberculosa, temporal bone osteomyelitis, facial nerve schwannoma, Fallopian canal hemangioma, petrous apex meningioma, paraganglioma and malignant tumors (primary and/or metastatic) 8.

Early surgical treatment is mandatory in cases of cholesteatoma that occur together with facial nerve functional deficit, in order to promote removal of the tumor responsible for the compression and injury of the neural tissue. The nerve should be decompressed both in the proximal and distal directions relative to the lesion, at a distance of 5 to 10mm, but the sheath should not be opened 8. In cases of facial nerve rupture and/or massive replacement of neural tissue by fibrosis (in chronic paralysis), we can have some procedures to try to restore the nervous function, such as for example, anastomosis of proximal and distal stumps of facial nerve after rerouting, nerve graft (greater auricular and/or sural) and hypoglossal-facial anastomosis 10.

The longer the duration of paralysis, the worse the prognosis, since postoperative functional recovery was deficient. The loss of terminal motor neurons associated with chronic reinnervation reduces the possibility of a significant restoration of neural functions 15.

In the patients studied in this analysis we could observe that the duration and grade of paralysis (initial), together with extension of lesion, were primordial factors for the determination of the functional recovery of the facial nerve.

Conclusion

Cholesteatoma is a rare cause of peripheral facial paralysis and the diagnosis of other pathologies, such as facial nerve Schwannoma, should always be kept in mind, especially in cases of congenital cholesteatomas, which can be asymptomatic for years. The surgery should be performed early in order to remove the cholesteatomatous lesion and to decompress the facial nerve, without opening the sheath owing to the risk of infection. The most frequently affected regions of the nerves are the tympanic portion and the 2nd knee region (transition of the mastoid to tympanic portion), even though in medially invasive cholesteatomas (with progression preferably by supralabyrinthine route) the geniculate ganglion is the most affected segment. We should bear in mind the possibility of nerve rupture, especially in cases of recurrent cholesteatomatous disease in which facial nerve decompression had been performed previously and the patient presented worsening of the nervous function some months or years after the surgery, being necessary in such occasions to perform neural grafting. In cases of chronic paralysis, the possibility of hypoglossal-facial anastomosis should be considered.

References

1. Swartz JD. Cholesteatoma of the middle ear: diagnosis etiology and complications. Radiol Clin North Am 1984; 22:15-34.

2. Soderberg KC, Dornhoffer JL. Congenital Cholesteatoma of the middle ear:occurrence of an "Open" lesion. Am J Otol 1998;19:37-41.

3. Huang TS, Lee FP. Congenital Cholesteatoma: review of twelve cases. Am J Otol 1994; 15:276-81.

4. Mafee M. MRI and CT in the evaluation of acquired and congenital cholesteatomas of the temporal bone. J Otolaryngol 1993; 22:239-48.

5. Waddell A, Maw AR. Cholesteatoma causing facial nerve transection. Clinical Records 2000:214-5.

6. Abramson M, Gross J. Further studies on a collagenase in middle ear cholesteatoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1971; 80:177-85.

7. Abramson M. Collagenolytic activity in middle ear cholesteatoma. Ann Otol 1969; 78:112-25.

8. Chu FWK, Jackler RJ. Anterior epitympanic cholesteatoma with facial paralysis: A characteristic growrh pattern. Laryngoscope 1988; 98:274-8.

9. Candela FA, Stewart TJ. The pathophysiology of otologic facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1974; 7:309-28.

10. Magliulo G, Terranova G, Sepe C, Cordeschi S, Cristofar P. Petrous bone cholesteatoma and facial paralysis. Clin Otolaryngol 1998; 23:253-8.

11. Atlas MD, Moffat DA, Hardy DG. Petrous Apex Cholesteatoma: Diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. Laryngoscope 1992; 102:1363-8.

12. Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, Krause JC, Richardson MA, Schuller DE. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 1998; 4:3047-75.

13. Sadé J, Fuchs C. Cholesteatoma: Ossicular destruction in adults and children. J Laryngol Otol 1994; 108:541-4.

14. Ylikoski J. Pathological features of the facial nerve in patients with facial palsy of varying aetiology. J Laryngol Otol 1990;104:294-300.

15. Axon PR, Fergie N, Saeed SR, Temple RH, Ramsden RT. Petrosal Cholesteatoma: Management considerations for minimizing morbidity. Am J Otol 1999; 20:505-10.

1 Affiliated Professor, Discipline of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP-EPM.

2 Physician, Master studies under course, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP-EPM.

3 Physician, Doctorate studies under course, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP-EPM.

Study conducted at the Sector of Otology, Federal University of São Paulo.

Article presented as Free Communication at the 36o Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, held on November 18 - 23, 2002.

Article submitted on May 23, 2003. Article accepted on August 20, 2003.