Year: 2003 Vol. 69 Ed. 4 - (19º)

Artigo de Revisão

Pages: 561 to 564

Nasal glioma: report of 3 cases and literature review

Author(s):

Ronaldo Frizzarini1,

Marcus M. Lessa2,

Elder Y. Goto2,

Richard L. Voegels3,

Luiz U. Sennes4,

Ossamu Butugan4

Keywords: nasal glioma, intranasal mass, new-born infant, congenital

Abstract:

Nasal glioma is a rare and benign congenital defect. This condition is diagnosed usually at birth time and requires early treatment to prevent facial deformations. We report three patients with nasal glioma that were diagnosed and treated at Otorhinolaryngology Department of Clinics Hospital of São Paulo University, and discuss clinical aspects, complementary exams, treatment and follow-up for each case. The first case was female, who presented a solid mass getting off left nasal fossae. The second case was male and presented cleft palate with a solid mass occupying the oral cavity. The third patient was male and had a solid mass over nasal pyramid. After surgical resection, all cases showed nasal glioma. Nasal congenital midline mass may be difficult to diagnose before histopathology, but is necessary to make an effort to do the correct diagnosis, letting an accuracy prognosis and appropriate surgical treatment.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Nasal glioma is a rare, benign congenital malformation that is habitually diagnosed right after birth, being detected in the neonatal period in 60% of the cases 17.

It was first described by Reid18 in 1852, even though the term "glioma" was introduced by Schmidt19 in 1900. In 1950, Black and Smith20 defined nasal glioma as a mass of extracranial glial tissue of congenital origin, manifesting intra and extranasally, originated from the nasal roof or close to it, which can be connected to the central nervous system (CNS) by a stem of glial tissue without being connected to the ventricular system or with the subarachnoid space of the CNS.

The purpose of our study was to report three cases of nasal glioma diagnosed and treated in our service and to perform a literature review.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

MAS, female Caucasian patient was referred to our service at the age of 2 months presenting a mass that exteriorized through the left nasal fossa since birth, with no growth, followed by serous secretion around it.

Upon physical examination, we detected a hardened mass, non-pulsatile and firm, of approximately 1.5cm in diameter, which was exteriorized through the left nasal fossa and did not increase in size as a result of crying. The right nasal fossa was narrowed, with septal deviation to the right (mass effect). Computed tomography scan (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a mass occupying the whole left nasal fossa, but without connection with the central nervous system.

Treatment selected was surgical removal via transmaxillary access, confirming there was no connection with the CNS or the skull base. The patient evolved well after the surgery and was discharged 3 days after surgery. The clinical pathology analysis confirmed the hypothesis of nasal glioma. Currently, five years after the surgery, the patient is under outpatient follow-up, with good progression and no tumor recurrence.

Case 2:

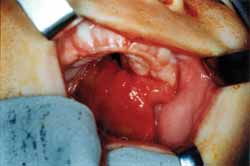

FDS, male Caucasian patient, aged 2 months, with history of mass in the oral cavity since birth, of constant size and without variation. The patient presented cleft palate through which the mass exteriorized, occupying the oral cavity, especially on the left side. Owing to the mass size, the patient had permanent Guedell canulla, so as to maintain the permeability of the airways, and with orogastric nasal tube for feeding.

Upon physical examination, it was noticed a mild orbital protrusion on the left and at oroscopy, there was micrognathia, cleft palate and reddish mass, non-pulsatile, of fibrous-elastic consistency covering the whole oral cavity, especially on the left aside, which did not increase in size as a result of crying. Computer tomography (CT scan) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed a mass occupying the left nasal fossa reaching the oral cavity through the cleft palate and retro-orbital cystic tumor suggestive of arachnoid cyst, without connection with the cerebral content. We decided to proceed a partial removal of the mass via intraoral access to have airways protection against humidity, whereas the neurosurgeon decided to have conservative management of the arachnoid cyst. The clinical pathology of the piece showed glial ectopia. The patient was discharged 5 days after the surgery feeling well, and currently he has been followed up for four years. The repair of the cleft palate was made and there has been no further growth of the remaining mass (arachnoid cyst), but he is still followed up by the neurosurgeon.

Case 3

VMC, male Caucasian patient aged 2 years, with compliant of nasal pyramid mass on the left since birth and increase in since for the past 1 year, followed by coriza and nasal obstruction on the left.

The physical examination revealed an external bulging in the nasal pyramid on the left of approximately 0.5cm in diameter, hardened, non-pulsatile mass with negative Furstenberg signal (does not increase in size with jugular vein compression). Rhinoscopy showed reduction of the left nasal vestibule region but with integral and normal mucosa. CT scan showed a mass in the left nasal pyramid but without connection to the CNS, which reduced the lumen of the left nasal fossa, suggestive of dermoid cysts.

We decided to perform external surgical removal through lateral incision, parallel to the nasal midline. The patient progressed well, was discharge on the second postoperative day. Clinical pathology revealed nasal glioma. The patient has been followed up for three years and he has progressed with no signs of recurrence. New CT scan was performed and it did not show recurrence.

Figure. Nasal glioma through cleft palate

DISCUSSION

Etiology of nasal glioma is still unknown, and it seems to be secondary to abnormalities of the normal embryological development. By the end of the 2nd week of embryogenesis, there is a small fontanel (nasofrontalis fonticulus) located between the frontal and nose bones. There is also the prenasal space located between the nasal bones and the nasal cartilaginous capsule, which extends as far as the skull base up to the nasal apex. Also at the beginning of embryogenesis, a dura diverticulum (with or without arachnoid or neural tissue) is projected anteriorly through the nasofrontalis fonticulus and/or inferiorly through the prenasal space. This diverticulum can be in contact and adhere to the skin. Normally, the diverticulum regresses with time and the bone closes down, creating the nasofrontal suture and cecum foramen (small canal that goes through the skull anterior to crista galli). A defect in regression of this diverticulum can leave ectodermic tissue through the path, preventing bone closure of the complex at this site, maintaining the cecum foramen enlarged and distorted by the crista galli. Depending on patency of the diverticulum and its content, the resulting lesion can be a dermoid cyst, glioma or encephalocele 9.

Encephalocele is the protrusion of cranial components through the bone defect of the skull base, which can contain meninx (meningocele) or meninx and cerebral tissue (meningoencephalocele) 2. Most encephaloceles are located posteriorly, but 15 to 20% of them are anterior 10. In all cases there is a defect of the skull base, which can lead to history of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak or meningitis 2.

Dermoid cyst is an ectoderm-originated tumor that can contain skin, hair, serous gland and sweat glands 21. Dermoid cyst is present at birth, even though it cannot be detected up to the moment it is inflamed or increased. It amounts to about 1 to 3% of all dermoid cysts of the body 2.

Nasal glioma, or cerebral nasal heterotopia, is considered an encephalocele that losses connection with the meninx of the intracranial space 5. However, 15 to 20% of the gliomas have a fibrous cord connecting the central nervous system through the cecum foramen 2, 5, 7, 16, 22. They are lesions with no family tendency, no potential for malignancy and no gender preference 1, 6, 7, 22, even though some authors believe that there is greater incidence in male patients, of 3:1 3, 26.

Differential diagnosis of nasal masses includes serous and epidermoid cysts, papilloma, inflammatory nasal polyps, carcinoma, hemangioma, lipoma, fibroma, meningeoma, lymphoma, sarcoma, tissues of neurogenic origin, nasal-labial cysts and nasal-lachrymal duct cyst 12, 23, 24.

Congenital masses of the nasal midline are rare, occurring in only 1:20,000 to 1:40,000 live births2, 6, 16, 21, being that there are only 250 cases of nasal glioma described in the literature1. In most reported cases, nasal glioma was not associated with other anomalies, but there are cases in which there are other malformations such as lip and palate cleft, choanal atresia, hydrocephalus, uretral duplication and extranumber finger 11. In our report, one case presented association with cleft palate. Normally, nasal glioma occurs around the nose, region of the midline, but there about 5% of them whose location in not nasofrontal 3, and it can occupy other sites such as the scalp, cheeks, soft palate, tonsil, tongue, middle ear, nasopharynx, oropharynx, submandibular region or the orbit 13, 17.

Clinically, nasal gliomas present as polypoid lesions that are firm, reddish and non-compressive. Normally they present as nasal obstruction at birth and it provides reduction of weight gain and dystrophy caused by problems of low nutritional intake 4. Hypertelorism can be evident at birth. The signal of Furstenberg (which is positive when there is increase in mass upon jugular vein compression) is negative, non pulsatile and has negative translumination 9, 15. In our report, 2 cases manifested with signals since birth and 1 case only after one year of age. In addition, all of them presented the lesion as a firm mass, non-pulsatile and with negative signal of Furstenberg, in agreement with the literature data.

As to location, 60% of the nasal gliomas are extranasal, 30% are intranasal and 10% are mixed 5, 6, 7, 15, 22, being that intranasal glioma is the one that presents the most intracranial extension 5. External nasal gliomas are normally located laterally to the midline and they can obstruct the vision or the nasal-lachrymal duct of the affected side 11, in addition to causing teleangiectasic skin 15. Nasal internal gliomas present as firm masses and sometimes they are pale and attached to the lateral wall of the nose or the middle concha, which can lead to respiratory difficulties 6, 11. In our report, 2 cases were intranasal and 1 case was extranasal.

The radiological study normally confirms the nature of the lesion. Pensler 9 reports that CT scan is an essential exam to detect the defect at the level of the cecum foramen and helps rule out intracranial communication. According to Lusk et al. 25, MRI can be useful to assess the soft parts and intracranial communication, in addition to not presenting exposure to radiation. MRI is important in the differential diagnosis of angiofibromas and intranasal gliomas 9. To Barkovich et al. 16 it should be the test of choice for the initial screening of the patient with midline nasal mass. In our findings, CT scan or MRI did not explain the connection of the mass with the CNS.

Harley15 described some findings of images that should have been investigated in patients with midline nasal masses: widening of the nasal bones, widening of the nasal septum, bifid nasal septum, bifid perpendicular plate, bifid crista galli, interorbital widening and defects of the cribiform, plus extension of intracranial masses. Sweet14 emphasized that negative results in imaging analysis, even with contrast, do not exclude intracranial communication.

Definite diagnosis is obtained through clinical pathology analysis, and excision biopsy is the preferred procedure. Incision biopsy is never indicated 15, because it may cause meningitis and CSF leak. Microscopically, the mass presents without capsule, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and varied proportion of fibrous and glial tissues. Glial cells are intertwined with vascular septa. Mitoses are absent, revealing the benign character of the lesion 2, 10. As to clinical analysis, we confirmed nasal glioma in the three cases.

In immunohistochemical analysis, cells are positive to Protein S-100, GFAP ("glial fibrilar acid protein"), NSE ("neuron-specific enolase") and Vimetidine, which indicate the glial or neuronal nature of the tumor 4, 8, 10. Tashiro et al.10 observed that neuronal cells are seldom present and not prominent. Dini et al.8 preferred immunohistochemistry to electron microscopy because it is more practical and describes that cell proliferation markers Ki67 and p53 are negative for the glioma.

Treatment of the craniofacial region is surgical excision9. Nasal gliomas are frequently extracranially excised and craniotomy can be necessary if there is communication with the CNS 15. According to Pensler 15, the surgery should be conducted in the first year of life to prevent deformation of the nasal bone and severe extracranial extension.

Yokoyama et al.5 advocated endoscopic access for the resection of glioma when it does not have intracranial extension, because external accesses are associated with postoperative esthetical problems and subsequent abnormal development of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

Recurrence of the lesion after primary extraction is of 4 to 10% 1, 4, 6, 8, probably because the surgeon had not had the histology diagnosis at the intraoperative time 4.

In the surgical treatment of our cases, we used different accesses depending on the location and extension of the lesion (transmaxillary, intra-oral and transcutaneous access). In no case did we notice recurrence of the lesion, and the shortest follow-up period was 3 years (all the cases are currently being followed-up).

FINAL REMARKS

Congenital masses of the nasal midline can be difficult to diagnose before the clinical pathology analysis, but we should do our best to have the correct diagnosis, providing accurate prognosis and appropriate surgical management. We point out the importance of surgical intervention still in the first year of life considering the diagnostic suspicion of nasal glioma, to prevent facial deformities and intracranial extension, despite the benign character of the lesion.

REFERENCES

1. Loundon N et al. Neuroglial Heterotopia. A propos of 8 Cases with Non-Nasofrontal Sites. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 1997;114(1-2):29-35.

2. Reid. Über Andeborene Hirnbrücke in der Stirn und Nasengegend. Illus Med 1852;3(1):133.

3. Schmidt MB. Über Seltene Spaltbildungen im Bereiche des Mittlerem Stirnfortsatzes. Virchous Arch Pathol Anat 1900;162:340-70.

4. Black BK, Smith DE. Nasal Glioma: Two Cases with Recurrence. Arch Neurol Psychiat 1950;64:614-30.

5. Pensler JM, Ivescu AS, Ciletti SJ, Yokoo KM, Byrd SE. Craniofacial Gliomas. Plast Reconstrut Surg 1996;98:27-31.

6. Lucky AW, Prendiville JS. Congenital Midline Nasal Mass in a Toddler. Pediatr Dermatology 2000;17(1):62-4.

7. Tashiro Y, Sueishi K, Nakao K. Nasal Glioma: An immunohistochemical and ultrastuctural study. Pathol Internat 1995;45:393-8.

8. Hughes Gb, Sharpino G, Hunt W, Tucker HM. Management of the Congenital Midline Nasal Mass: A Review. Head Neck Surg 1980;2:222-33.

9. Yokoyama M, Inouye N, Mizuno F. Endoscopic Management of Nasal Glioma in Infancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;51:51-4.

10. Shah J, Patkar D, Patankar T, Krishinan A, Prasad S, Limdi J. Pendunculated Nasal Glioma: MRI Features and Review of the Literature. J Postgrad Med 1999;45:15-7.

11. Barkovich AJ, Vandermarck P, Edwargs MSB, Cogen PH. Congenital Nasal Masses: CT and MR Imaging Features in 16 Cases. Am Journal of Neuroradiol 1991;12:105-16.

12. Gorenstein A, Kern EB, Facer GW, Lows ER JR. Nasal Gliomas. Arch Otolaryngol 1980;106:536-40.

13. Rouev P, Dimov P, Shomov G. A Case of Nasal Glioma in a New-born Infant. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2001;58:91-4.

14. Ducic Y. Nasal Gliomas. J Otolaryngol 1999;28:285-7.

15. Sanz JJ, Benitez PA, Bernalsprekelsen M, Alos LL. Glioma of the Sphenoid Sinus in an Adult. Acta Otorrinolaring Esp 2000;51(6):539-42.

16. Bluestone CD, Stool SE. Pediatric Otolaryngology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990. p. 718.

17. Haafiz AB, Sharma R, Faillace WJ. Congenital Midline Nasofrontal Mass. Clin Pediatr 1995;34(9):482-6.

18. Heacock GL, Tagi F et al. Clinical and Pathologic Diagnosis. Pathologic Quis Case 1. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;118:548-551.

19. Reilly J, Koopman Cf, Cotton R. Nasal Mass in a Pediatric Patient. Head Neck 1992;415-9.

20. Thomson HG, Al-Qattan MM, Becker LE. Nasal Glioma: Is Dermis Involvement Significant? Ann Plast Surg 1995;34:168-72.

21. Levine MR, Kellis A, Lash R. Nasal Glioma Masquerading as a Capillary Hemangioma. Ophth Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;9(2):132-4.

22. Schroth M, Wolf S, Bentizien S, Wagner M, Rupprecht T. Relapsing Nasal Glioma in a Three-Week-Old Infant. Med Pediatr Oncol 2000;34:375-6.

23. Harley EH. Pediatric Congenital Nasal Masses. E.N.T. 1991;70:28-33.

24. Lusk RP, Lee PC. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Congenital Midline Nasal Masses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986;95:303-5.

25. Sweet RM. Lesions of the Nasal Radix in Pediatric Patients: Diagnosis and Management. South Med J 1992;85(2):164-9.

26. Dini M, Russo G, Colafranceschi M. So-Called Nasal Glioma: Case Report With Immunohistochemical Study. Tumori 1998;84: 398-402.

1Resident physician, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo.

2Post-graduation, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo.

3Ph.D., Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo.

4Full Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo.

Study conducted at the Division of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo.

Address correspondence to: Ronaldo Frizzarini - Rua Santa Germana, 7 - Sao Paulo - SP CEP 03627-060

Tel.: (55 11) 9378-3638 / 6091-6007 - Fax (55 11) 3068-9855 - e-mail: ronaldofrizzarini@bol.com.br

Article submitted on June 10, 2002. Article accepted on September 29, 2002.