Year: 2001 Vol. 67 Ed. 5 - (4º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 627 to 633

Prevalence of otologic symptoms in temperomandibular disorders: 126 case studies

Author(s):

Maria I. N. Pascoal 1,

Abrão Rapoport 2,

José F. S. Chagas 3,

Maria B.N. Pascoal 4,

Claudiney C. Costa 4,

Luis Antonio Magna 5

Keywords: temporomandibular articulation, otologic symptom

Abstract:

Introduction: A presence of otologic symptoms associated to the temporomandibular disorders (TMD) is discussed since six decades ago, however its etiology still stays obscure. Study design: Prospective clinical randomized. Aim: In that study it was appraised the prevalence of otologic symptoms in TMD, the correlation with the muscular pain and the absence of posterior teeth. Material and Methods: 126 patients, presented TMD, were appraised through questionnaire about their symptoms, palpation of the masticatory muscles, temporal, masseter, lateral pterygoid medial, pterigoyd, digastric, temporal muscle tendon, esternocleidomastoid and trapezius and panoramic and transcranian X-rays and plaster´s models of the superior and inferior arcades. The data obtained were analyzed through Exact Test of Fisher, with p value < 0,05. Results: The otologic symptoms were presented in 80% of the patients (50% presented hear pain 52% aural fullness, 50% tinitus, 34% dizziness, 9% sensation of vertigo and 10% told hypoacusis). The palpation revelated lateral pterigoyd as the most sensitive 94%, followed by the temporal muscle ( 69%), masseter (62%), digastric (60%), medial pterigoyd (50%), temporal muscle tendon and sternocleidomastoid (49%) and trapezius (42%). The muscular pain and otologic symptoms were statistically significant in the masseter and esternocleidomastoid muscles. Tinitus, aural fullness and otologic pain presented high significant correlation to each other. There was not significance between the absence of teeth and otologic symptoms. Conclusion: 1) otalgia, tinitus, aural fullness and dizziness were prevalentes 2) the otologic symptoms present in TMD can be relation with the muscular pain in masseter and esternocleidomastoid 3) there was not correlation between the otologic symptoms and the absence of posterior teeth.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The presence of otologic symptoms related to temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders started to be discussed six decades ago with Costen 6. The author correlated symptoms such as hearing loss, otalgia, ear fullness, tinnitus and vertigo to the loss of posterior teeth. In his opinion, such an event caused the mandibular condyle to be displaced towards the anterior tympanic wall, causing its reabsorption. Another hypothesis correlated the symptoms to the painful spasm of the musculature26. However, in subsequent years, the idea that prevailed was that the posterior displacement of the mandibular condyle could lead to the onset of otologic symptoms, even though other abnormal positions of the glenoid cavity that had been detected when checking the anterior or superior projections of the glenoid cavity also produced painful symptoms29.

Hypertony of facial muscles can also develop temporomandibular disorder, a factor that questions the definite presence of the dental factor in the TMJ disorder: Currently, the multiple factors that may trigger the disease include dental positioning as a very relevant fact, but not as the single one17,18. It leaves no doubt that loss of posterior teeth and posterior displacement of the condyle are not the only unfavorable conditions that lead to otologic symptoms, as had been previously stated.

When it was said that compression of structures, such as that of the maxillary artery, corda tympani and auricular-temporal nerves and the auditory tube, was responsible for the symptoms, a fundamental piece of data was omitted. Compressions that normally lead to symptoms, as a whole, are continuous and the TMJ is in constant movement (in average, 1,800 times a day), which are severely disturbed by the presence of a TMJ disorder.

Anatomical, psychological and pathological factors may contribute to the onset of the disease. However, the diversity of causes and factors has a common link connecting them: muscle pain, which is the result of the continuous activity of facial muscles, associated or not to stress8, may be associated with hyperreflexia or local inflammatory process, promoted by mechanical trauma in articular tissues2,20,24.

Pain will define protection mechanisms that interfere in the physiological standards of the nearby structures, such is the case of ear and TMJ. Physiological mandibular movements, which promote swallowing, mastication and suction, are modified; by the central nervous system in order to limit the progressive damage of articular tissues, which may determine the degeneration of articulation and, sometimes irreversibly, ankylosis24.

Epidemiological studies in the past sixty years evaluated that 50 to 60% of the population in general, without prevalence of age, sex and color, present some sign of mastication system disorder, and only 10% present significant symptoms that make them seek for medical treatment20. Therefore, many signs result in subclinical symptoms and, if left untreated, they may lead to TMJ disorder owing to lack of appropriate treatment or information, since otologic symptoms do not clearly indicate the existence of a TMJ disorder.

The diversity of factors that may determine the onset of the disease has hindered the hard task of identifying a single cause to explain the otologic symptoms in TMJ disorders3,7. Another factor that could generate some conflict is the wide range of other causes that may express otologic symptoms, cases that are routinely presented in the otorhinolaryngologist daily practice.

Based on these assumptions, the present study intended to assess the prevalence of otologic symptoms in patients who have TMJ disorders, relating presence of the pathology with (1) muscle pain and (2) absence of posterior teeth.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Our sample constituted of patients referred to the Sector of Buco-Maxillo-Facial Surgery and Traumatology at Hospital a Martenidade Celso Pierro, from Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas (PUCCAMP), who had suspicion of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. Patients were seen between June 1999 and June 2000 and referred to the Ambulatory of Otorhinolaryngology for exclusion of symptoms caused by otologic causes. It consisted of 126 patients, 22 male (17.5%) and 104 female (82.5%) subjects. The youngest patient was 13 years old and the oldest one was 77 years old (Table 1), mean age of 37 years and median age of 35.

The criteria employed for patient selection were advocated by the Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for Orofacial Pains by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP)20, and at least three of the following signs or symptoms should be present: pain on mastication or facial muscles, limited or asymmetrical mandibular movement, noise or sounds in the TM joints and alteration of imaging of hard tissues.

Clinical assessment was carried out with a symptomspecific questionnaire, muscle and TMJ palpation, impression of upper and lower dental arches for the confection of cast models and x-ray analysis with panoramic face radiography and lateral transcranial TMJ film.

The questionnaire consisted of personal identification data, otologic, neurological and cervical symptoms referred in TMJ disorders, and functional aspects of mandibular movement. Instead of employing medical terms such as otalgia, ear fullness, tinnitus, cephalea and cervical pain, we used pain in the ear, pressure in the ear, noise in the ear and headache so that patients could easily understand it.Table 1. Correlation between presence of otologic symptoms and muscular pain.

*** absence of significance.

In the physical examination, we carried our palpation of muscle groups of the head, face, mouth and neck, which are involved in the physiological processes of the mastication system. Using the indicator and middle fingers we inspected simultaneously and bilaterally the external muscles of the face: temporal muscle and its three anterior, posterior and middle bundles, medial pterygoid; superficial masseter, posterior bundle of the digastric; trapezius. We also carried out digital palpation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle using the thumb and indicator finger applied bilaterally and symmetrically.

In the muscles of the mouth, palpation was made with the indicator fingers bilaterally, but separately, on the deep bundle of masseter and anterior bundle of digastric. Next, we palpated the attachment of temporal muscle tendon in the retromolar space, simultaneously and bilaterally with the indicator, and finally, the lateral pterygoid muscle with the small finger located on the region of the pterygoidmaxillary fossa region, bilaterally and one side at a time. Muscles were palpated in all their extension following the sequence: temporal, digastric (posterior bundle), medial pterygoid, masseter (superficial bundle), digastric (anterior bundle), masseter (deep bundle), temporal muscle tendon, lateral pterygoid, sternocleidomastoid and trapezius. The purpose of bilateral and simultaneous palpation, if possible, was to help the patient compare pain in symmetrical muscles.

At the end, we palpated the TM joints in two steps: with the indicator finger we checked the presence of periauricular pain and with the small finger, placed in the external acoustic canal, we checked the presence of articular pain during mandibular movement.

We classified the information provided by patients as pain if it complied with the criteria of AAOP20: 1) pain, regional, non-penetrating pain aggravated by muscle function, when mastication muscles are not involved; 2) hyperirritability sites, frequently palpated within a tense range of muscle tissue; 3) Hyperalgesia in the region of irradiated pain.

Statistical analysis complied with numerical criteria: signs and symptoms: 0 absence, 1 presence; muscle palpation: 0 absence of pain, 1 presence of pain; dentition status: 0 dentulous patients, 1 partially dentulous patients, 2 edentulous patients; posterior dentition status: 0 posteriorly dentulous patients, 1 partially posteriorly dentulous patients, 2 posterior edentulous patients.

Data were recorded in Excell 5.0 for Windows spreadsheets. We carried out the statistical analysis using Fisher's exact test, software SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for four variables: correlation of pain upon palpation and otologic symptoms, correlation of all symptoms, correlation of different muscular pains and correlation of otologic symptoms and absence of posterior dentition. Significance value was p<0.05.

RESULTS

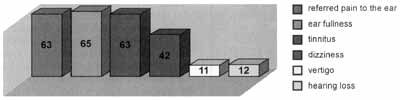

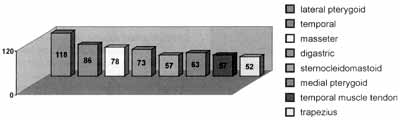

We found otologic symptoms in 80% of the studied patients, and 63 patients reported pain in the ear; 65 ear fullness, 63, tinnitus, 42, dizziness; 11, vertigo; and 12 reported hearing loss (Graph 1). Muscles presented painful palpation in 95% of the patients and lateral pterygoid was the most sensitive muscle in 188 patients, followed by temporal muscle in 86 patients, masseter in 78, digastric in 73, medial pterygoid in 63, temporal muscle tendon and sternocleidomastoid in 57 patients and trapezius in 52 patients (Graph 2). Statistical correlation between pain and otologic symptoms was significant for pain referred on the anterior temporal (p<0.016), superficial masseter (p<0.005), digastric anterior bundle (p<0.06), medial pterygoid (p<0.05), sternocleidomastoid (p<0.005) muscles, and temporal muscle tendon (p<0.002). In the symptom of ear fullness, there was statistical significance for temporal muscle (p<0.006), sternocleidomastoid (p<0.05) and temporal muscle tendon (p<0.010). As for tinnitus, there was statistical significance for temporal muscle (p<0.04), masseter (p<0.016), digastric (p<0.01), sternocleidomastoid (p<0.06), and temporal muscle tendon (p<0.0007). As for dizziness, we found statistically significant differences for the masseter (p<0.011) and sternocleidomastoid (p<0.05) (Table 2). For correlation of symptoms, we found statistically significance between referred pain and ear fullness (p<0.002), referred pain and tinnitus (p<0.001) and fullness and tinnitus (p<0.0002). In the correlation between pain upon palpation of the sternocleidomastoid and the masseter, we found high significance (p<0.00013) (Figure 1). As to status of posterior teeth, the results revealed its presence in 41.25%, partial presence of posterior teeth in 22.25% and there were 36.5% of posterior edentulous patients (Graph 3). Correlation between otologic symptoms and absence of posterior dentition did not produce statistically significant differences in any of the studied symptoms: (p<0.64) for referred pain, (p<0.082) for tinnitus, (p<0.95) for dizziness and (p<0.64) for ear fullness.

Graph 1. Prevalence of otologic problems in the sample.

Graph 2. Prevalence of muscle pain in the sample.

Graph 3. Prevalence of posterior dentition in the sample.

Table 2. Correlation of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The theory of posterior condyle displacement6 resultant from the loss of posterior teeth as the triggering factor was not found in our sample. Out of the total number of patients with TMJ disorder, only 36.5% presented loss of posterior teeth and 60% of them had otologic symptoms. By correlating absence of posterior teeth and otologic symptoms, there was no statistical significance.

The hypothesis that otologic symptoms are related to an increase in muscle tone appeared from electromyography studies showing that pain in muscles and joints of the head stimulates the afferent receptors of facial, trigeminal, hypoglossus and cervical nerves. The response is the increase in muscle tone, especially facial, tongue and mandible muscles, synthesized in an anti-pain reaction to limit movement and prevent the damage caused to the TMJ15.

Figure 1. Concomitant hypertrophy of masseter and sternocleidomastoid muscles.

In inflammatory processes, there is a summation of significant nociceptive nervous impulses that may interfere in the operation of the involved organ by inhibiting impulses in nearby areas. One example is the inhibition of peristaltic movement in the presence of an abdominal inflammatory process, such as appendicitis. This phenomenon is found in organs that respond to deep somatic pain, such as the visceral structures and muscles, among them the facial muscles. It explains in a coherent fashion the symptoms of referred pain and hyperalgesia of muscles that were reported by our patients2.

Functional relation between ear structures and TMJ dates from the embryonic formation process, because both structures derive from, Meckel's cartilage. From an anatomical standpoint, we clearly see the close correlation among the different muscles involved in the joint and the ear structures. Temporal, masseter and lateral and medial pterygoid muscles are attached around the ear. It is from the lateral pterygoid muscle that the malleus ligament of the tympanic membrane emerges. The anatomical relation between palatine muscles and the mouth and auditory tube, which is responsible for balancing the pressure between the middle and external ear, is equally important13,19,12.

Facial innervation, both motor and sensitive, is profuse and involves trigeminal, facial, vagus, glossopharyngeal and cervical nerves, but it is not segmented. The region of the pinna clearly shows it, because this small facial territory shelters the whole innervation24.

The interaction between mouth and pharynx nerves and muscles is essential because swallowing, phonation and breathing functions are determined by these organs. As reported in the anatomical aspects, it is known that these functions directly influence the ear. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the mouth, ear and pharynx are intimately and functionally related1,8,13,19.

In healthy subjects, the set of structures operates harmonically, thanks to the synergism between facial and neck muscles, mediated by nervous impulses. This reality is modified in patients who have TMJ disorders because the movements made by the joints everyday, such as masticate, swallow, speak, suck, amount to 1,800 times a day8, and are gradually modified in the process of muscle and articular disorganization of the disease25,28. Based on the definitions described above, we may justify the presence of symptoms in the correlation between otologic symptoms and muscle pain upon palpation.

The significance between otalgia and muscle pain in all palpated muscles, except for trapezius and middle temporal muscles, confirms the statement that referred pain in the ear could derive from any head and neck structure that participates in the nervous connection of temporal bone and periauricular region1. It includes any muscle that is inserted close to the ear and that presents tone alterations that causes pain. Therefore, painful facial muscle spasms could lead to this symptom.

As for the symptom of ear fullness, we found significance between ear fullness and pain in the sternocleidomastoid, temporal muscle tendon and posterior temporal muscles. We believe that the correlation between this symptom and TMJ disorder relies on the influence that the disease has on modification of tone of the anterior bundle of digastric and temporal muscles during swallowing10, leading to poor functioning of the auditory tube16. The same principle would explain the presence of tinnitus that demonstrated significance in all palpated muscles, except for the medial pterygoid muscle and the middle temporal bundle14,16. Anatomical relations between TMJ and the middle ear, through the disk-maleolar ligament (Pinto's minor ligament)9,23, whose fibers come from the lateral pterygoid muscle8,23, responsible for vibration of the ossicle chain, were not conclusive in our study, because since it has been reported before, it was the most sensitive muscle for palpation. Nevertheless, our results did not show statistical correlation between this muscle and tinnitus, and it has been said that this muscle is not strong enough to pull the ossicles9.

Dizziness presented significance with pain in the sternocleidomastoid, masseter and medial pterygoid muscles. This symptom reported in the temporomandibular disorder could be justified by the alteration of contraction of anti-gravitation muscles, which sternocleidomastoid and masseter are part; the process is that when uncoordinated afferent information from labyrinthic organs and sight and proprioception organs are sent to the central nervous system, cerebellum, reticular formation and cerebral cortex respond with the sensation of dizziness8,11.

It is important to bear in mind that the two other balance routes, the labyrinth and the visual pathway, are also located in the head. Their alteration, resultant from muscle hypercontraction, tends to stimulate the labyrinth, which is sensitive to any alteration of posture11.

In the symptom of hearing loss, we fund significance for pain upon palpation of sternocleidomastoid and trapezius. The explanation for the existence of this symptom, even if in a small percentage, suggests that the patient interprets the sensation of ear fullness or tinnitus as a hearing loss. Sensitive muscles that were significant for this symptom are similar to the muscles correlated with the symptoms of ear fullness and tinnitus. The absence of audiometry abnormalities when patients are referred to otorhinolaryngologists confirms that patients do not have hearing loss related to TMJ disorders.

The presence of statistical high significance between symptoms of tinnitus and ear fullness and referred pain shows the correlation between these symptoms and TMJ disorders.

We noticed that two muscles were statistically significant for all symptoms: masseter and sternocleidomastoid. The justification for the interaction between the two muscles with different innervation is caused by the co-activation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle during the contraction of the masseter, as well as the inhibition of sternocleidomastoid and masseter, via trigeminal stimulation, especially in the presence of painful processes2,4,5,25,27. Some body positions reflect increase in muscle tone of sternocleidomastoid, digastric and masseter21. Confirming our hypothesis, we found high significance in the statistical correlation of presence of pain in the two muscles. We did not find data from the literature that had analyzed this statistical correlation to compare our data.

Another palpable piece of evidence on the interaction of the otologic symptoms and muscle pain in the sternocleidomastoid and the masseter is provided by the literature. It says that symptom relief is obtained with treatment for TMJ disorder14,12. The description of regression of otologic symptoms after the treatment with flat acrylic dental device; effective to help muscle hyperactivity, shows reduction of the activity of the masseter muscle, demonstrated by means of electromyography20,25.

The encouraging results of improvement of otologic symptoms with such treatment define the need for further and comprehensive research between the interaction of muscle pain and symptoms. More precise studies involving electromyography and otoneurologic analysis may put an end to doubts, maximizing diagnosis and improving the quality of life of our patients.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results, we concluded that:

1) Tinnitus, referred pain, ear fullness and dizziness were prevalent symptoms in our sample.

2) Ear referred pain, tinnitus, ear fullness and dizziness were significant in the correlation of pain and masseter and sternocleidomastoid muscles palpation.

3) The increase in muscle contraction of these two groups of muscles may be responsible for otologic symptoms of TMJ disorders.

4) There was no correlation between absence of posterior teeth and otologic symptoms in our sample.

REFERENCES

1. BAUER, C.A.; JENKINS, H.A. - Otologic symptoms and syndromes, in CUMMINGS, CW.; FREDRICKSON, JM.; KRAUSE, CJ.; HARKER, L.A.; SCHULLER, D.E.; RICHARDSON, M.A. Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, St. Louis, Mosby - Year BOOK. Inc_ 2547-60, 1998.

2. BELL, W.E. - Outras dores viscerais in_______Dores Orofaciais. Classificação, Diagnóstico a Tratamento. Rio de Janeiro, Quintessence Books, 3° Edição: cp XIV 278-88, 1991.

3. BRITTO, L.H.; KOS, A.O.A.; AMADO, S.M.; MONTEIRO, C.R.; LIMAM, A.T. - Alterações otologicas nas desordens temporomandibulares. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol., 66-327-32, 2000.

4. BROWNE, P.A.; CLARK, G.T.; YANG, Q.; NAKANO, M. Sternocleidomastoid muscle inhibition induced by trigeminal stimulation. J. Dent. Res. 72:1503-8, 1993.

5. CLARK, G.T.; BROWNE, P.A.; NAKANO, M.; YANG, Q. - Co-activation of sternocleidomastoid muscles during maximum clenching. J. Dent. Res.72:1499-502, 1993.

6. COSTEN, J.B. - A syndrome of ear and sinus symptoms dependent upon disturbed function of temporomandibular joint. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 43:1-11, 1934.

7. D'ANTONIO, W.E.P.A.; IKINO, C.M.Y.; CASTRO, S.M.C.; BALBANI, A.P.S.; JURADO, J.R.P.; BENTO, R.F. - Distúrbio temporo-mandibular como causa de otalgia: um estudo clínico. Rev Bras. Otorrinol. 66:46 50, 2000.

8. DOUGLAS, C. R - Fundamentos fisiológicos da atividade Estomatopônica. In DOUGLAS, C. R. Patofisiologia Oral. São Paulo, Pancast Editora, 1ª Edição. 1998, 115-61.

9. ECKERDAL, O. - The petrotympanic fissure: A link connection the tympanic cavity and temporomandibular joint. J. Cranio. Pract. 9:15 22, 1991.

10. FALDA, W.; GUMARÃES, A.; BÉRZIN, F. - Eletromiografia dos músculos masseters a temporais durante deglutição a mastigação. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 52:151-7, 1998.

11. GANANCA, M.M.; CAOVILLA, H.H. - Equilíbrio e Desequilíbrio in_______GANANÇA, M.M. - Vertigem tem cura? São Paulo, Lemos ed. 1ª Edição, 13-9, 1998.

12. GARCIA, A.R.; SOUSA, V. - Desordens temporomandibulares: causa de dor de cabeça a limitação da função mandibular. Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. 25.481-6, 1998

13. GARDNER, E.; GRAY, D. J.; O'RAILLY - A Orelha in Anatomia. Rio de Janeiro. Guanabara-Koogan, 4ª Edição 19, 605-17, 1978.

14. GIORDANO, A.; NÓBILO, K.A. - Placa estabilizadora de Michigan e sensação do zumbido. Rev. Ass. Paul. Cir. Dentistas, 49:395-9, 1995.

15. HU, JW.; YU, X.; VERNON, H.; SESSLE, B.J. - Excitatory effects on neck and jaw muscle activity of inflammatory irritant applied to cervical paraspinal tissues. Pain 55:243-50, 1993.

16. JASTREBOFF, P.J; GRAY, W.C; MATTOX, D.E - Tinnitus and Hyperacusis in_________CUMMINGS, CW.; FREDRICKSON, J.M.; KRAUSE, C. J.; HARKER, L.A.; SCHULLER, D.E.; RICHARDSON, M.A. Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, St. Louis, Mosby - Year BOOK. Inc, 3198-224, 1998.

17. LASKIN, D.M. - Etiology of the pain-dysfunction syndrome. DADA 79.147-52, 1969.

18. McNEILL, C. - History and evolution of TMJ concepts. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 83:51-60, 1997.

19. NAVARRO, J.A.C.- Anatomia de Cabeça a Pescoço - Manual de disseção. Faculdade de Odontologia de Baum, Universidade de São Paulo, 1993.

20. OKESON, J.P. - Diagnóstico diferencial a Considerações sobre o Tratamento das Desordens Temporomandibulares. In________Dor Orofacial. Guia de Avaliação, Diagnóstico a Tratamento. São Paulo. Quintessence ed., 4ª Edição, 113-85, 1998.

21. PALAZZI, C.; MIRALLES, R.; SOTO, M.A.; SANTANDER, H.; ZUNIGA, C.; MOYA, H. - Body position effects on EMG activity of sternocleidomastoid and masseter muscles in patients with myogenic cranio-cervical-mandibular dysfunction. J. Craniomand. Pratic. 14.200-9, 1996.

22. PERRY, H.T.; XU, Y.; FORBES, D.P. - The embryology of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomand. Pratic. 3:126-32, 1985.

23. RODRIGUES VASQUEZ, J.F.; MERIDA VELASCO, J.R.; JIMENEZ COLLADO, J. - Relationship between the temporomandibular joint and middle ear in human fetuses. J. Dent. Res. 72:62-6, 1993.

24. SESSLE, BJ.; HU, JW.; AMANO, N.; ZHONG, G. - Convergence of cutaneous, tooth pulp, visceral, neck and muscle afferent onto nociceptive and non-nociceptive neurons in trigeminal. Pain. 27.219 35, 1986.

25. SHAN, S.C.; YUN, W.H. - Influence of an occlusal splint on integrated electromyography of the masseter muscle. J Oral. Rehabil. 18:253 6, 1991.

26. SHWARTZ, L. - Temporomandibular joint syndromes. J. Prost. Dent. 7489-94, 1957.

27. SOHN, MX; GRAVEN-NIELSEN, T.; ARENDT- NILSEN, L.; SVENSSON, P. - Inhibition of motor unit firing during experimental muscle pain in humans. Muscle Nerve 23:1219-26, 2000.

28. TSUGA, K.; AKAGAWAY; SAKAGUCHI - A short-term evaluation of the effectiveness of stabilization-type occlusal splint therapy for specific symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome. J. Prosthet. Dent. 61:610-3, 1989.

29. WEINBERG, L. A. - The role of stress, occlusion, and condyle position in TMJ dysfunction-pain. J. Prost. Dent 49:532-45, 1983.

30. WIDMALM, S.E.; WESTERSSON, P.; KIM, L; PEREIRA, F.J.; LUNDH, H.; TASAKI, M.M. - Temporomandibular joint pathologies related to sex, age and dentition in autopsy material. Oral Surg, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 78:416-25, 1994.

1 Dentist. Master degree, Post-Graduation in Head and Neck Surgery, Complexo Hospitalar Heliópolis.

2 Coordinator of the Post-Graduation in Head and Neck Surgery, Complexo Hospitalar Heliópolis.

3 Head of the Service of Head and Neck Surgery, Hospital a Maternidade Celso Pietro - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas.

4 otorhinolaryngologist. Master degree, Post-Graduation in Head and Neck Surgery Complexo Hospitalar Helópolis.

5 Geneticist. Faculty Professor, Department of Medical Genetics, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

Master degree thesis presented at the Post-Graduation in Head and Neck Surgery, Complexo Hospitalar Heliópolis.

Address correspondence to: Maria Isabel Nogueira Pascoal. R: Dr Arnaldo de Carvalho n° 555 apto 113.Bonfim. CEP- 13047-090 - Fone (55 19) 33851703. (55 19) 32430642 Campinas - São Paulo

Article submitted on February 13, 2001. Article accepted on June 18, 2001.