Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 5 - (24º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 755 to 760

"Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: cases report and literature review."

Author(s):

Daniela Salgado Alves Vilela 1,

Fernando Oto Balieiro 1,

Alessandro M. F. Fernandes 2,

Edson I. Mitre 3;

Paulo R. Lazarini 4.

Keywords: Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, facial nerve, paralysis, decompression

Abstract:

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is a rare disease of unknoun etiology, with hereditary predisposition. It is characterized by orofacial swelling, fissured tongue and recurrent peripheral facial palsy. After several episodes of facial palsy, permanent deficit may occur, leading to speech and feeding disabilities, and emotional problems. These important sequelaes justify the special attention required to the management of the facial palsy. The purpose of this study is to review main clinical findings on Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and analyze the treatment options. We have reported four cases followed in our department and compared their treatments to the literature data. In two cases the recurrent episodes of facial palsy resolved spontaneously to normal facial function, without medication therapy. In one case a partial decompression of the facial nerve was performed, returning to normal function afterwards. In another case, a recurrent episode of facial paralysis ocurred after the partial decompression of facial nerve. The patients with Melkersson-Roshental syndrome and who show facial palsy with unsatisfactory evolution or recurrent episodes may undergo surgical procedure.

![]()

Introduction

Facial movement deficit is an affection that results in great limitation to human beings. Difficulties in facial expressions during communication, feeding disorders and relationship disabilities are some of the aspects that lead to significant impairment of quality of life of these patients. In most of the cases this limitation is temporary and specific, progressing to improvement and restoration of facial functions. Sometimes, these episodes are repetitive, generating patients' self-consciousness and leading to psychiatric problems and permanent motor sequelae.

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is a rare disease, of unknown etiology, characterized by the presence of orofacial edema, fissured tongue and recurrent peripheral facial palsy. The most frequent and characteristic symptom is orofacial edema, with facial palsy present in 20 to 30% of the cases6. Despite the fact that the incidence of paralysis is relatively low in this syndrome, the cases that come to the Otorhinolaryngologist can present as the main complaint deficiency of facial movement, requiring that the key purpose of the therapy be quick restoration of facial mimics.

The present study intended to review the clinical characteristics of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome trying to elucidate its etiology and to discuss the existing treatment regimes in the literature. We also reported four clinical cases followed up in the ambulatory of ENT at Santa Casa de São Paulo and their treatment approaches.

TABLE 1. Distribution of cases of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome concerning gender, current age and incidence of facial palsy.

TABLE 2. Distribution of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome cases according to initial graduation, treatment and progression.

Case report

Case 1

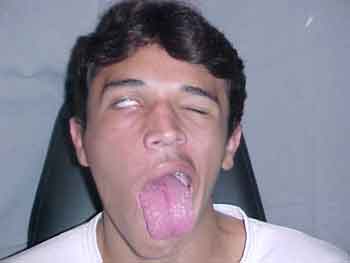

A.S.L., 17 year-old male subject, came to the service with peripheral facial palsy for one month on the right side. He reported two previous episodes, both on the right, and the latter had happened one year before. The episodes were not treated and presented favorable evolution, with complete recovery. At physical examination, the patient presented fissured tongue (Figure 1) and facial palsy classified as grade V of House & Brackman (figure 2), but we did not detect orofacial edema. Schirmmer's test showed lachrymation present and symmetrical and at immitanciometry, there was absence of stapedial acoustic reflex. The patient was followed up for four weeks and presented little improvement of the palsy, reason why we indicated decompression of the facial nerve by transmastoid access, approaching the tympanic and mastoid portions. Three months after the surgery, there was improvement of facial movement, going to grade III of House & Brackman. Currently, the patient is on the 7th postoperative month, presenting grade I classification on the operated side (right), but he now presents grade II peripheral facial palsy on the left, treated with PO prednisone (figure 3).

Case 2

P.M.G., 23 year-old female patient, presented peripheral facial palsy on the right 15 days before. She referred previous history of facial palsy on both sides, with five previous episodes, all of them untreated. The first episode had happened at the age of 14 and on the right side, followed by palsy on the other side 10 months later. These two episodes had left definite sequelae, plus the three other episodes, being two on the left and one on the right.

At physical examination, the patient presented grade V of House & Brackman on the right and grade III on the left side. There was no orofacial edema but the tongue was fissured. Lachrymation was symmetrical and the stapedial acoustic reflex was present in both ears. The patient was treated with prednisone in regressive doses for 16 days, and facial nerve decompression with transmastoid access was indicated owing to lack of clinical improvement. One month after the surgery, the patient presented significant improvement of the palsy, going down to grade II on the sixth postoperative month. About one year after the surgery, there was a new episode of peripheral facial palsy on the right, classified as grade VI, but with asymmetrical lachrymation. Since there had been no improvement after three weeks, we have scheduled facial nerve decompression through middle fossa, heading towards the meatal and labyrinthic portions.

Case 3

M.C.S., 16 year-old female patient, came to our service after presenting three episodes of peripheral facial palsy on the left since childhood. She reported that the episodes had started with orofacial edema on the left, being the first at the age of 4, the second at 7 and the third at 11 years. In the two first episodes the symptoms regressed spontaneously after few days, but the last one had left a mild facial paresis. At physical examination, she presented mild edema on left side, fissured tongue and grade II paralysis. She is currently under clinical follow up, with reduction of facial edema and total remission of paresis, with normal facial movement.

Case 4

M.D.G.M., 20 year-old female patient, came to our service with peripheral facial palsy on the right and complaint of reduced sensitivity of the lips on the same side for 2 months. She reported two episodes of previous peripheral facial palsy, both conducted without treatment and with spontaneous resolution. The first had happened two years before, affecting the right side and less severe than the current one, improving spontaneously in three weeks. The second episode had happened 18 months before, affecting the left side and showing little motor facial abnormalities. At clinical examination, the patient presented right facial palsy classified as grade IV, presence of fissured tongue, ocular-labial synkinesis on the left (contralateral) and mild diffuse lip edema. The lachrymation test was symmetrical. She was submitted to head MRI and there was no evidence of facial nerve abnormalities in the whole pathway. The patient was clinically followed up with a very favorable evolution, and currently has grade II paralysis on the right facial side, five months after onset.

Figure 1. Photo of the tongue showing the fissures.

Figure 2. Frontal photo of the patient showing peripheral facial palsy on the right.

Figure 3. Frontal photo of the seven postoperative month after partial decompression of the facial nerve on the right. A new episode of peripheral facial palsy was noticed on the left.

Discussion

The first reports of the association of peripheral facial palsy and facial edema were made by Hubschman, in 1894, and subsequently by Rossolimo, in 1901, who added the frequent report of headache to the general picture. In 1928, Melkersson reported in details the case of a 35 year-old woman who manifested recurrent peripheral facial palsy and facial edema and later Rosenthal added the presence of fissured tongue to the characteristics of the syndrome, consolidating the classical description1, 14.

The Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is characterized by recurrent and non-painful orofacial edema, fissured tongue and recurrent uni or bilateral facial palsy. The symptoms can be concomitant or isolated, with intervals of months or years. The syndrome, in general, is manifested with one or more components, characterizing as mono or oligosymptomatic, and complete cases are rare.

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome has an estimated incidence of 0.08% and the etiology is unknown6. It commonly starts at childhood or adolescence with greater prevalence in women on the first, second and sixth decades of life. Men are affected in smaller proportions and in age ranges different from those in females. There is no racial preference, but most of the cases were described in European countries, with isolated reports in South Africa, Japan and Middle East8.

The predominant finding is orofacial edema, characterized by being non-painful, non-erithematous, non-pruritous and asymmetrical. It classically affects the upper lip, which gets two to three times larger than normal, with short duration and at irregular intervals. It may also affect the cheeks, lower lip, nose, eyelids, maxillary mucosa and temporal region1. The edema can be uni or bilateral, frequently on the same size as the paralysis. After recurrent episodes, it may persist definitely causing facial deformities.

Recurrent lip edema that affects as an isolated sign is known as Miescher granulomatous keilitis, considered as a monosymptomatic and typical form of the syndrome. It is characterized by the presence of a chronic inflammatory process, with epithelioid non-caseous granulomas and circulating mononuclear infiltrate, Langhans' giant cells and perivascular lymphoplasmocytarian infiltrate6.

We noticed that the incidence of orofacial edema, the main characteristic of the syndrome, was under reported compared to the literature, affecting two of the four studied cases. The low rates are probably due to the fact that most patients do not search for medical care owing to the tendency of spontaneous recovery and sometimes because of its little facial esthetical repercussion.

Peripheral facial paralysis is normally a sudden affection, either uni or bilateral, complete or incomplete and clinically non-distinguishable from Bell's palsy. The onset is normally before the age of 20 years and tend to recover completely1. As a result of disease progression, the episodes of palsy become more frequent and long lasting, and they may cause residual paresis and synkinesis. The chorda tympani nerve can also be affected, compromising gustation in the two anterior thirds of the tongue.

The fissured tongue is also known as plicated, scrotal, folded, cerebral-like or crocodile tongue, which is a common finding in the syndrome. It is considered an anatomical variation, but it has a pathological meaning5. According to Hawkins (1972), its incidence in the general population is about 0.5%, affecting about 4% of the cases of idiopathic peripheral facial palsy and 25% of the patients with recurrent facial palsy; its presence is considered a possible sign of predisposition to the onset of facial palsy9. Even though fissured tongue is a common sign, the definition of the syndrome does not necessarily require its presence, and it may be detected in the general population without pathological significance.

Some signs and symptoms defined as minor criteria are also part of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. The affection of other cranial nerves, migraine, and salivary and lachrymal gland dysfunction and pupil motricity are the so-called minor criteria, in addition to the presence of hyperhydrosis, hyperacusis, acroparesthesia, epyphora, hyperageusia and multiple ophthalmologic findings such as lagophthalmus, exposure keratitis, blepharocalasia, retrobulbar neuritis, retina vein anomaly and paralysis of medial rectus muscle1, 12.

Some theories try to explain the onset of the syndrome, such as the one proposed to relate its origin to genetic, allergic and infectious factors. The genetic transmission theory is sustained by reports that studied patients with the syndrome and their first and second-degree relatives. According to Lygidakis et al. (1979), the first publication made by Rosenthal (1931) and later by New & Kirch (1933), Ekbom & Wahlstrom (1942) and Kunstadter (1965) detected signs and symptoms in various generations of different families11. Smeets et al. (1994) reported the existence of the syndrome in two generations of five different families and three generations of a sixth family. The same study demonstrated that genetic transmission was defined as autossomal dominant, presenting variable expression. Lygidakis et al. (1979) described the signs of the syndrome in seven members of four different generations of the same family. Meisel-Stosiek et al. (1990) reported a long study with 42 patients who presented signs of the syndrome and assessed their family members, concluding that the syndrome presented likely hereditary predisposition with multifactorial origin. In 1994, Smeets et al. identified a gene translocation in one patient, suggesting the possible location of a autossomal dominant gene responsible for the syndrome15.

The allergic theory is not very consistent, since the process is limited only to the face, without systemic manifestations or presence of modifications in the number of blood eosinophils1.

As to infectious disease, many of them have been related to the syndrome, such as syphilis, oral bacterial infections, benign lymphogranulomatosis and viral infections, especially herpes infection. Cairns, in 1972, reported the case of a patient with recurrent peripheral facial palsy, facial edema, migraine and presence of multiple herpes eruptions2. The characteristics of recurrence of the syndrome suggest a viral etiology, showing periods of exacerbation after long periods of quiescence.

Orofacial edema and facial paresis can be sequels of a disease that has chronic evolution and repetitive episodes. As a predominant symptom in the literature and capable of producing definite deformities, orofacial edema is treated as a distinct form, depending on the evolution phase. In the acute phase, the edema is treated with cold compressive dressings to reduce the edema, and by topical lubricants, to avoid skin fissures. In the chronic phase, various treatments are proposed, such as use of anti-histaminic, antibiotics, dapsone, clofazimine, sulphasalazine, corticoid steroids (systemic or intra-lesion injections), local radiation and reductive keiloplasty, all of them with varied and temporary results4, 8.

Kesler et al., in 1998, reported the case of a patient treated with high doses of methylprednisolone for two months, showing significant improvement of facial edema and palsy10. Of the cases described in this study, two presented orofacial edema that reduced spontaneously or with the use of corticoids. The use of systemic corticoids, indicated on the treatment of facial palsy in the initial phase, helps the reduction of the edema and the recovery of the facial esthetics. Despite the varied reports found in the literature, both the systemic corticoids and intra-lesion injections seem to present the best results, reducing the volume of facial edema and preventing its progression4. In our experience, the onset of facial edema is not a frequent clinical characteristic, tending to solve spontaneously without sequelae.

The treatment of facial palsy can follow the same standards used in the treatment of Bell's palsy. The natural trend to resolution within three weeks, even without the use of medication, suggests that clinical follow-up is the right approach. Two of our cases presented good evolution, with total regression of symptoms and absence of motor sequelae. The use of systemic corticoids, such as prednisone, can reduce nerve edema and accelerate clinical improvement. In this period, the patient should be submitted to serial electroneurography in order to have control of neural degeneration. As to cases that do not benefit from this clinical intervention and present signs of neural degeneration on electrical exams, nerve decompression should be considered.

The main difficulty in trying to define the therapy is to find cases in which recurrence is frequent, leading to possible greater sequelae. The indication of surgery to facial nerve decompression seems to be appropriate. When to operate: in the acute or asymptomatic phase? In our plan of care, for patients that have history of recurrence and sequelae, but are not in the acute phase, we prefer to have a conservative approach. In such situations, we wait for a new episode of the process to perform the surgery. The decompression using transmastoid access in patients with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome produced different results in the literature, and recurrence of paralysis was described even after the surgery. Dutt et al. (2000) reported a case of recurrent episodes of facial palsy after partial decompression of the nerve4. Probably, the meatal and labyrinthic segments were involved in the new episodes.

Total decompression of facial nerve using combined transmastoid and middle fossa access seems to be the best therapeutic option for cases of recurrent facial palsy, as demonstrated by Nyberg & Fisch in 1985 13. Edema affects the nerve in all its extension, and decompression of meatal and labyrinthic portions is essential for good surgical result. Graham & Kartush (1989) reported six cases of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome successfully submitted to facial nerve total decompression7. Canale & Cox (1974) reported one case of syndrome submitted to bilateral facial decompression and perfect recovery of facial movement3.

The tendency to recurrence by relapsing of the inflammatory process of the nerve favors the onset of irreversible sequelae, and surgical treatment is then the method indicated to prevent this process. As described in case 2, the nerve was initially affected in its tympanic and mastoid portion, but suffered a new inflammatory insult in the meatal and labyrinthic segments.

Closing Remarks

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is an affection frequently present in otorhinolaryngologists' routine practices. The knowledge about its evolution and possible sequelae determines the need for a broad spectrum therapy, ranging from clinical observation to surgical measures for facial nerve decompression.

REFERENCES

1. Alexander RW & James RB - Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: review of literature and report of case. J. Oral Surg., 30: 599-604, 1972.

2. Cairns RJ - Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome. Proc. R. Soc. Med., 54: 217, 1961.

3. Canale TJ & Cox RH - Decompression of the facial nerve in Melkersson Syndrome. Arch. Otolaryngol., 100: 373-4, 1974.

4. Dutt SN; Mirza S; Irving RM; Donaldson I - Total decompression of facial nerve for Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. J. Laryngol. Otol., 114: 870-3, 2000.

5. Ekbom KA - Plicated Tongue in Melkersson's Syndrome and in Paralysis of the facial nerve. Acta. Med. Scand., 138: 42-7, 1950.

6. Glickman LT; Gruss JS; Birt BD; Kohli-Dang N - The Surgical Management of Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg, 89 : 815-21, 1992.

7. Graham, M.D.; KARTUSH, J.M. - Total facial nerve decompression for recurrent facial paralysis: An up-date. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 101: 442-4, 1989.

8. Greene RM & Rogers RS - Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: A review of 36 patients. J .Am. Acad. Dermatol., 21: 1263-9, 1989.

9. Hawkins DB; - Melkersson's syndrome: an unusual case. J. Laryngol. Otol., 86: 943-7, 1972.

10. Kesler A; Vainstein G; Gadoth N - Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome treated by methylprednisolone. Neurology, 51: 1140-1, 1998.

11. Lygidakis C; Tsakanikas C; Ilias A; Vassilopoulos D - Melkersson-Rosenthal's syndrome in four generations. Clin. Genet., 15: 189-92, 1979.

12. Meisel-Stosiek M; Hornstein OP; Stosiek N - Family Study on Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome: some hereditary aspects of the disease and review of literature. Acta. Derm. Venereol., 70: 221-6, 1990.

13. Nyberg P & Fisch U - Surgical treatment and results of idiopathic recurrent facial palsy. In: PORTMANN M., ed. Facial nerve. New York, Masson, 1985, 259-68.

14. Saberman MN & Tente LT - The Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome. Arch. Otolaryng., 84: 74-8, 1966.

15. Smeets E; Fryns JP; Van Den Berghe H - Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and the autossomal t (9;21)(p11;p11) translocation. Clin. Genet., 45: 323-4, 1994.

1 Resident Physician, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

2 Master in Otorhinolaryngology, Instructor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

3 Master and Ph.D. in Otorhinolaryngology, Professor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

4 Professor, Ph.D., Graduation and Post-graduation Courses, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Affiliation: Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Address correspondence to: Daniela S. A. Vilela

Departamento de Otorrinolaringologia da Irmandade de Misericórdia da Santa Casa de São Paulo

R. Cesário Mota Jr., 112 - 4o. andar - CEP - 01277-900 - São Paulo - SP. Tel/fax: 2228405 (danielasav@ig.com.br)

Study presented as poster at II Congresso Triológico de Otorrinolaringologia, held on August 22 - 26, 2001, in Goiania.

Article submitted on September 05, 2001. Article accepted on January 10, 2002