Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 5 - (23º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 749 to 754

Mandibular condylar fractures: classification and treatment

Author(s):

Luiz C. Manganello 1,

Alexandre A. F. Silva 2

Keywords: mandibular condyle, condylar fractures, mandibular fractures

Abstract:

Condylar fractures are considered one of the most controversial fractures in face regarding treatment and diagnostic difficulty. Choosing the best treatment, such as surgery, inter maxillary fixation, physiotherapy or their association is directly related to fractures type, patient age and functional impairment degree. Clinical findings are relevant for proper diagnostic but image is fundamental for a precise treatment indication. We present a novel classification based on the condyle deviation and also propose a treatment for each type of fracture regarding age and clinical symptoms. We illustrate this paper with a description of two cases, one submitted to surgical and other to clinical treatment.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Facial fractures are important due to their physical, emotional and socio-economic consequences. Mandibular condylar fractures are among the facial fractures whose treatment is most debatable. This is due to the fact that the temporomandibular joint allows mandible movements and is directly related to dental occlusion.

The objective of the present study is to classify mandibular condylar fractures according to treatment and report two clinical cases, one submitted to surgical treatment and another treated conservatively, and to analyze indications and counter-indications of both treatments, in addition to the advantages and disadvantages of each one.

LITERATURE REVIEW

According to Asadi and Asadi2 (1986), in a study coordinated by the Trauma Committee of the American College of Surgeons, mandibular fractures account for 34.9% of all facial fractures, and mandibular condylar fractures account for 17.25%.

The signs and symptoms of condylar fractures are: pain, limited mandible movement, impaired dental occlusion, facial asymmetry (due to a deviated chin to the fractured side) and mandibular retro positioning (in bilateral fractures). According to Hayward and Scott6 (1993), various factors influence the decision to perform treatment surgically or not, among them: patient's age, site of fracture, the extent of dislocation of the fractured segment, other associated facial fractures, presence of teeth and easiness to establish occlusion. Most condylar fractures are treated de surgically by maxillary-mandibular blocking, rubber physical therapy, observation only along with liquid diet, or association of both.

Despite the fact that Jeter et al.7 (1988) utilized the intra-oral access, most surgeons prefer the extra-oral access, for surgical treatment of condylar fractures. Rigid internal fixation has been performed more than steel suture osteosynthesis, because it promotes primary bone consolidation without post-operative maxillary-mandibular blocking with a greater benefit for patients (Ellis and Dean5, 1993).

CASE REPORT 1

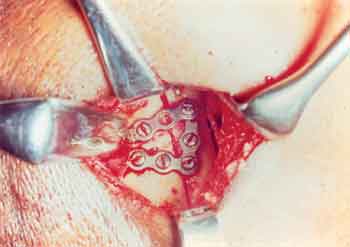

Male, 52 year-old patient, victim of an automobile accident. He was riding on the passenger seat and was not wearing a seat belt. He hit his chin against the panel leading to a bilateral condylar neck fracture and subsequent mandibular retropositioning, with the right condyle dislocated towards the anterior-medial position, and the left one within articulation limits (Figures 1 and 2). Treatment proposed consisted in reduction and rigid internal fixation of the right dislocated condyle, aiming at re-establishing the vertical dimension and performing a conservative treatment of the left fracture possible with rubber physical therapy. During surgery it was not possible to perform the reduction of the right condyle through the submandibular approach due to its pronounced medial dislocation. The option was a vertical osteotomy of the branch and removal of the proximal segment to make it easier to locate the condyle and perform intra-operative fixation of the condyle and proximal stump complex, that was then fixed as a single piece to the mandibular branch with 2.0mm mini-plates (Figures 3-a, 3-b and 3-c). During the 10 day post-operative period rubber physical therapy was begun for the left fracture. Two years after surgery the reestablishment of the anterior-posterior direction of the mandibular projection and absence of radiographically visible condylar resorption was observed (Figures 4 and 5).

CASE REPORT 2

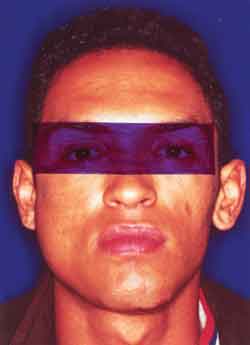

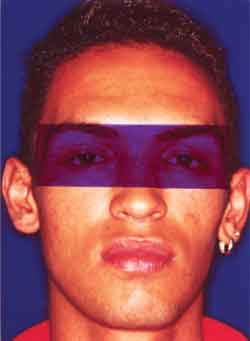

Male 21 year-old patient, victim of a fall from a bicycle, hitting his chin on the ground. He presented with a left mandibular condylar fracture without dislocation leading to mouth opening limitation, left posterior cross-bite and a deviated chin towards the fractured side (Figures 6, 7 and 8). Management was conservative using only rubber to guide occlusion, correct chin deviation and un-cross the bite (Figures 9-a, 9-b and 9-c and 10). The treatment resulted in a normal dental occlusion, and an adequate mouth opening, without deviations.

Figure 1. Profile photo showing mandibular retropositioning as a consequence of bilateral condylar fracture.

Figure 2. Panoramic film showing fracture of right condyle neck.

Figure 3-a. Demarcation of vertical osteotomy of the branch by submandibular access to facilitate the location of the condyle and later the reduction and rigid internal fixation.

Figure 3-b. Complex of condyle and proximal stump of the vertical osteotomy that were fixed on the table.

Figure 3-c. Complex of condyle and proximal stump fixed to the mandibular branch of 2.0mm in diameter.

DISCUSSION

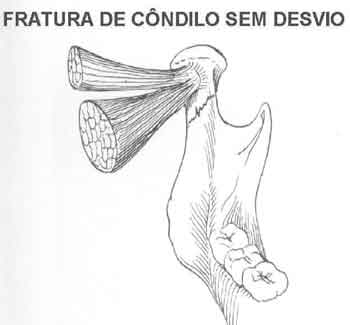

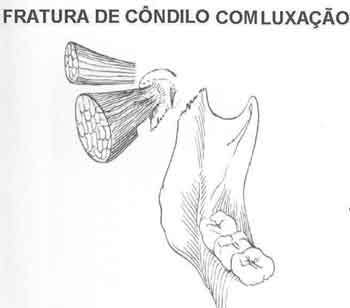

Condylar mandibular fractures may be basically classified as unilateral or bilateral, with (Figure 12) and without dislocation (Figure 11-a and 11-b). Fractures without condylar dislocation may present a deviated or non-deviated condyle in relation to the rest of the mandible, and the treatment is always conservative with rubber physical therapy to correct occlusion. We may find condylar fractures that do not affect dental occlusion, and in these cases treatment is a liquid diet for 2 weeks and observation. Surgical treatment with condylar fixation is indicated for fractures with dislocation in order to reestablish the vertical dimension in patients that are over 8 years old. Surgery is not necessary before this age group due to the high capacity of bone remodeling and growth of the mandibular bone, mainly at the condyle level, allowing for a conservative treatment (Hayward and Scott6, 1993).

The region of the mandibular condyle neck is a very vulnerable part of the mandible both in children and adults. Injuries to the temporomandibular joint are almost always caused by a mandible trauma that spreads to the condylar region. Fractures are rarely due to direct impact on the pre-auricular region. The direction and level of the force applied are essential for understanding the mechanism of injury. An axial force applied against the mandibular symphysis runs towards the body bilaterally, and may result in a bilateral condylar fracture. If the force is perpendicular to the mandibular body it can result in a fracture at the impact site and possibly in a contra-lateral condylar fracture (Barros and Manganello3, 2000).

Imaging tests allow us to determine the anatomical level of fracture as intra-capsular, high sub-condylar or of the condylar neck, and low sub-condylar; the extent and type of dislocation of the fractured segment in relation to the articular fossa and mandibular branch. There is usually an anterior-medial dislocation due to the action of the lateral pterygoid muscle, and lateral, superior and posterior dislocations are rare. There are more, and more severe complications in patients submitted to surgery and the fact may be credited to the severity of the fracture. We may say that dislocated fractures tend to be more complicated in regard to patient recovery (Amaratunga1, 1987).

According to Zide and Kent15 (1983), mandibular condylar fractures may be associated with other mandibular and other bone face fractures. The surgical or non-surgical treatment of condylar fractures is quite controversial in the literature, mainly for adults (Raveh et al.12, 1989; Upton14, 1991). Many condylar fractures may be treated conservatively with food restriction and analgesics, mainly in children that have a large bone remodeling potential and in the elderly in whom maxillary-mandibular block may lead to nutritional impairment. Hayward and Scott6 (1993) have stated that various factors should be considered for choosing treatment, such as: the extent of dislocation of the fractured segment in relation to the articular fossa, the level of the fracture, patient's age and the presence of other associated facial fractures.

Amaratunga1 (1987) agrees that condylar fractures in children submitted to surgical treatment present better results, because children still have a remodeling capacity, while there is a functional adjustment in adults. There are however, data in the literature indicating that between 6 and 35% of patients treated in this manner had some type of clinical symptom characteristic of temporomandibular dysfunction, which persists more in adults, mainly as a deviation during mouth opening (Asadi and Asadi2, 1986; Dunaway and Trott4, 1996).

Figure 4. Postoperative 2 years later, where we can see restoration of anterior-posterior mandibular angle.

Figure 5. Postoperative towne radiography 2 years after, showing rigid internal fixation of right condyle and good positioning of left condyle.

Figure 6. Frontal photo showing deviation from the mentonian to the left, corresponding to the fractured condyle side.

Figure 7. Posterior crossed bite.

Figure 8. Panoramic film showing left condyle fracture without dislocation.

The extra-oral approach is preferable to the intra-oral one for patients treated surgically (Raveh and col.12, 1989). The sub-mandibular incision offers the best surgical field, making it easier to perform fixation of 2.0mm mini-plates and recapture the condyle whenever branch vertical osteotomy is necessary. According to Ellis and Dean5 (1993), although the retromandibular incision is not frequently mentioned in the literature, it has advantages such as a shorter distance between the incision and the condyle, better access because it allows anterior-superior retraction of tissue and better esthetical results. Some authors prefer the pre-auricular incision mainly for high sub-condylar fractures (Dunaway and Trott4, 1996; Raveh and col.12, 1989). The Risdon approach is indicated for subcondylar fractures, despite the difficulty to reduce the condyle in fractures with dislocations, and its high percentage (30%) of facial nerve neuropraxia (Ellis and Dean5, 1993).

The conservative treatment concept in children with condylar fractures (Joos and Kleinheinz8, 1998) is valid, although we consider it very difficult to make treatment decisions based on X-rays. Surgical procedures would be indicated for patients over 8 years of age, and always in extra-capsular comminuted fractures or with dislocation, that necessarily present a major functional impairment or that do not respond well enough to conservative treatment. The surgical treatment is indicated for reestablishing the vertical dimension in bilateral fractures, in which at least these requirements are fulfilled for at least one of the fractures.

In general, during condylar fracture reduction, the mandibular angle needs to be inferiorly repositioned in order to reposition the fractured segment. In cases of condylar fracture with a major medial and/or anterior dislocation in which the above mentioned technique does not apply, a vertical osteotomy of the mandibular or sub-condylar branch at the sigmoid incisure towards the posterior border of the mandibular branch can be performed (Mikkonen and col.10, 1989). When the osteotomy is performed in order to recapture the condyle, the vascular supply to the osteotomized segment is interrupted, a fact that may contribute to bone resorption and some cases may evolve to necrosis (Upton14, 1991; Suuronen and col.13, 1994). Manganello9 (1998) showed a patient treated by this method, with a 3 year follow-up in which condylar resorption was minimum.

Mitchell11 (1997) attributed condylar resorption to the non-physiological position of the condyle after its fixation and increase in functional power. In two cases of bilateral condylar fracture only one condyle with a major dislocation was reduced, making return to normal function possible. It is believed that the non-reduced condyle may lead to overload to the operated side, thus leading to condylar resorption. Raveh and col.12 (1989) contra-indicate rigid internal fixation or osteosynthesis with steel suture for condyles dislocated out of the mandibular fossa because of condylar resorption and dysfunction with impairment of the contra-lateral joint.

There may be a fracture of the plate fixed on the condyle whenever the condyle is fixed in a non-physiological position so that functional forces overrule the rigidity of the mini-plate (Ellis and Dean5, 1993). We believe, however, that the mini-plate to be used in fractures with dislocation should not be smaller than 2.0 mm, reaching up to 2.4 mm due to chewing forces that are distributed in this region and that can lead to its fracture.

Figure 9-a. Rubber physical therapy to guide occlusion.

Figure 9-b. Occlusion after two weeks of rubber physical therapy.

Figure 9-c. Mouth opening of 45mm after 2 months.

Figure 10. Correction of mentonian deviation at the end of conservative treatment.

Figure 11-a. Fracture of condyle without dislocation and deviation (conservative treatment).

Figure 11-b. Fracture of condyle without dislocation and with medial deviation (conservative treatment).

Figure 12. Fracture with medial dislocation owing to lateral pterygoid muscle action (surgical treatment indication for patients over 8 years of age).

CLOSING REMARKS

Most mandibular condylar fractures are treated clinically, restoring mandibular movements and the most adequate occlusion possible. Surgery should be indicated for specific cases due to the morbidity that may result from it. Children treated for condylar fractures need follow-up during growth, because they may present impairment of facial development because of the fracture.

REFERENCES

1. Amaratunga NA. A study of condylar fractures in Sri Lanka patients with special reference to the recent on treatment, healing and sequelae. Brit J Oral and Maxillofac Surg 1987;25:391-397.

2. Asadi GA, Asadi Z. Site of the mandible prone to trauma: a two year retrospective study. Int Dental Journal 1986;46:71-73.

3. Barros JJ, Manganello LCS. Traumatismo Buco-Maxilo-Facial. 2a edição. São Paulo: Roca; 2000. p.231-64.

4. Dunaway DJ, Trott JA. Open reduction and internal fixation of condylar fractures via an extended bicoronal approach with a masseteric myotomy. Brit J of Plastic Surg 1996;49:79-84.

5. Ellis e, Dean J. Rigid fixation of mandibular condyle fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993;76:6-15.

6. Hayward J, Scott RA. Fractures of mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;1:57-61.

7. Jeter Ts, Van Sickels, Nishioka Gj. Intraoral open reduction with rigid internal fixation of mandibular subcondylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988;46:113-116.

8. Joos V, Kleinheinz J. Therapy of condylar neck fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998;27:247-254.

9. Manganello LC. Condylar reconstruction with costho condral graft after mal united condylar fracture. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plast 1998;13:342-345.

10. Mikkonen P, Lindqvist C, Pihakari A, Iizuka T, Tandpaukku P. Osteotomy-osteosynthesis in displaced condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989;18:267-270.

11. Mitchell D.a. A Multicentre audit of unilateral fractures of the mandibular condyle. Brit J Oral Maxillofac Surg 35:230-236, 1997.

12. Raveh J, Vuillemin T, Ladrach K. Open reduction of dislocated of dislocated, fractured condylar process: indication and surgical procedure. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989;47:120-126.

13. Suuronen R, Vainionpa S, Hietanen J, Vasenius J, Lindqvist C. The effect of osteotomy and osteosynthesis in mandibular condyle. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;23:174-179.

14. Upton L. Management of Injuries to the temporomandibular Joint Region. In: Fonseca R, Walker R. Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma. Philadelphia: Saunders company; 1991. p. 418-433.

15. Zide MF, Kent JN. Indications for open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1983;1:89-98.

1 Dentist, Oral and Maxillo-Facial Surgeon. Plastic Surgeon.

2 Dentist, specialized in Surgery and Oral and Maxillo-Facial Traumatology.

Study conducted at Instituto da Face

Address correspondence to: Luiz Carlos Manganello - Rua Itapeva, 500 - 1o andar - Cj: 1C

CEP 01332-000 - Bela Vista - São Paulo - SP - Tel/Fax: (55 11) 288.7168 - E-mail: mangane@attglobal.net

Article submitted on November 14, 2001. Article accepted on February 21, 2002