Year: 2013 Vol. 79 Ed. 3 - (19º)

Artigo de Revisão

Pages: 382 to 390

Measures of quality of life in children with cochlear implant: systematic review

Author(s): Marina Morettin1; Maria Jaquelini Dias dos Santos2; Marcela Rosolen Stefanini3; Fernanda de Lourdes Antonio4; Maria Cecília Bevilacqua5; Maria Regina Alves Cardoso6

DOI: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130066

Keywords: child; cochlear implants; hearing loss; quality of life; rehabilitation of hearing impaired.

Abstract:

The use of cochlear implant (CI) in children enables the development of listening and communication skills, allowing the child's progress in school and to be able to obtain, maintain and carry out an occupation. However, the progress after the CI has different results in some children, because many children are able to interact and participate in society, while others develop limited ability to communicate verbally. The need for a better understanding of CI outcomes, besides hearing and language benefits, has spurred the inclusion of quality of life measurements (QOL) to assess the impact of this technology.

OBJECTIVE: Identify the key aspects of quality of life assessed in children with cochlear implant.

METHOD: Through a systematic literature review, we considered publications from the period of 2000 to 2011.

CONCLUSION: We concluded that QOL measurements in children include several concepts and methodologies. When referring to children using CI, results showed the challenges in broadly conceptualizing which quality of life domains are important to the child and how these areas can evolve during development, considering the wide variety of instruments and aspects evaluated.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have reported that children with severe and/or profound hearing loss (HL) may substantially benefit from using a cochlear implant (CI), together with proper auditory rehabilitation. These children have greater likelihood of acquiring oral language1 and being integrated in regular schools2, extending their chances of participating in activities and being part of the world of sounds3.

To perform activities and participate in the auditory world means to communicate and, consequently, communication is directly related to socializing, since social interactions occur by means of verbal communication4. The social aspect is one of the most important parts of a child's global development; it integrates the meaning of "quality of life", as well as other issues associated with functionality, physical and mental well-being4. Therefore, if the CI provides for hearing and language development and, consequently, the development of communication skills, such progress, because of CI use, would bring quality of life improvements for children with hearing loss.

However, although the CI can usually improve the quality of life (QL) of children, there is but a very limited number of studies in our field investigating such aspects5. This is a surprising finding, since hearing interference has been well documented, especially in regards of social performance, self-esteem and acceptance at school6; and these issues are even more relevant in children with severe and/or profound hearing loss7.

Studies in this field evaluate aspects which are more associated with auditory, language and speech performance, school type, and analyze the cost-effectiveness of the CI treatment1,3,8,9. More attention has been given to the measures carried through in image/behavior clinic/laboratory than the collection of information at the level of CI user's functionality or other significant factors associated with their bio-psycho-social development10.

Concerning the progresses achieved in the field of Audiology, especially with the pediatric population using CI, healthcare professionals must consider that the factors affecting the results are so numerous, and only one part of them can be investigated by means of tests or other instruments used in clinical routine11. Moreover, a detailed investigation concerning other aspects of life is not only relevant for the parents and physicians, but also for setting up healthcare policies12, allowing for proper resource assignments to take care of the different social needs, service programs and specific interventions for this population13.

Thus, to measure health-related quality of life (HRQL), which is a unique and personal perception of physical, mental and social well-being in diverse situations and activities9, it is important to evaluate the multidimensional impact of hearing loss and cochlear implant use in the life of children, complementing the results of the clinical measures14.

But, specifically in the pediatric population, to measure the HRQL is not an easy task. Numerous methodological issues permeate this type of evaluation, and to measure the state of health of a child requires choices concerning which health aspects are relevant, which preferences are of interest (child, parents, professors, doctors, etc.), the values that must be used, and an entire series of other contextual and psychometric issues that must be tended to15.

The challenge is in putting it within a comprehensive concept which HRQL aspects are important for the child, and how such aspects may progress during his/her development are determining factors in this type of assessment. For example, HRQL domains for a 5 year girl who is starting school can be different from those for an 18 year old who is just starting to drive. This fact directly reflects the choice of instrument to be used, since it must identify and evaluate all the relevant factors for the population being studied. Moreover, most of the time, HRQL questionnaires for children are frequently filled up by the parents or care-givers and studies have shown a poor correlation between the scores from the parents and the child vis-à-vis mental and social aspects, and a better correlation concerning physical domains16. Thus, the interpretation of the HRQL results must take into consideration the questionnaire's respondent and, when possible, the evaluation of the parents and that of the child must be done together17.

Having all these issues associated with the measure of quality of life in children and trying to guide the bibliography survey with high scientific evidence, we carried through a systematic revision of the literature in order to pinpoint quality of life of children with cochlear implants, and find out which are the main aspects assessed in this population and factors associated with quality-of-life measuring.

METHOD

As an essential principle of evidence-based studies, the investigated issue in this study was: "Which are the main quality of life aspects assessed in children using CI and the factors related with its results?".

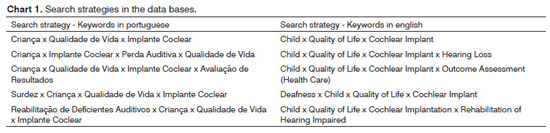

The search strategy used in the bibliographical revision was oriented by the combination of seven keywords indexed in the DecS (health keywords) in Portuguese and English, employing the keywords in groups with at least two keywords (Chart 1).

The chosen scientific databases for the search were: LiLacs, MedLine, scieLo, cochrane Library, PubMed, embase, institute for scientific information (isi) and science Direct. For the purposes of this study, we considered the publications produced during the period from january of 2000 through september of 2011, and the last manual search was carried out in electronic databases in september of 2011.

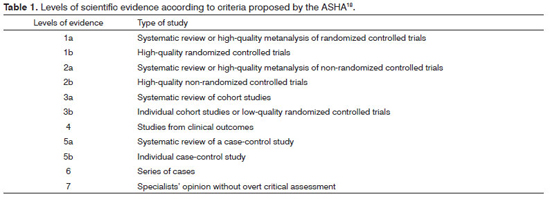

The choice of papers followed inclusion criteria based on confining the subject matters to the objectives of this paper. The adopted criteria were:Participants - Children with cochlear implants; Intervention - Cochlear implant; Measured outcomes - Quality of life by means of questionnaires; Time - Published in last the 11 years (2000-2011); Language: Papers written in Portuguese, English and Spanish; Types of studies - Papers published in indexed journals with evidence levels 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b and 4, in accordance with the criteria proposed by the American Speech Language Hearing Association (ASHA)18 (Table 1).

We took off those studies carried out with special groups of children with cochlear implant and other disorders, such as cerebral paralysis, auditory neuropathy, syndromes, auditory nerve hypoplasia, internal component re-implant, bilateral implant and other complications.

The selection of the studies was made in three stages and guided by the above-established criteria. Initially, four revisers analyzed all the studies identified by the combinations of the keywords in all the databases proposed, by analyzing the study title, selecting the papers which gathered the pre-established eligibility criteria (1st stage). Following that, we checked to see if the abstracts had information available on the use of some quality-of-life assessment instrument in children (2nd stage). The cases in which the title or the abstract left margins for doubt we studied the entire texts (3rd stage) to later be deemed pertinent to the subject of study and then be reviewed. The main data for each paper retrieved was carefully collected by means of a standardized protocol for the present study.

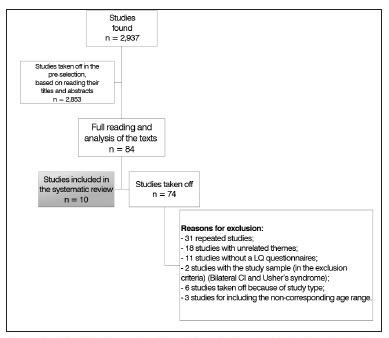

A total of 2,937 papers were identified in all the databases. In a pre-selection of these citations, based on reading the titles and summaries of all studies found in the electronic search, we took 2,853 studies off, 84 papers were selected and read in their entirety (Flowchart 1).

Flowchart 1. Number of studies identified and selected for inclusion in the systematic review and reasons for exclusion.

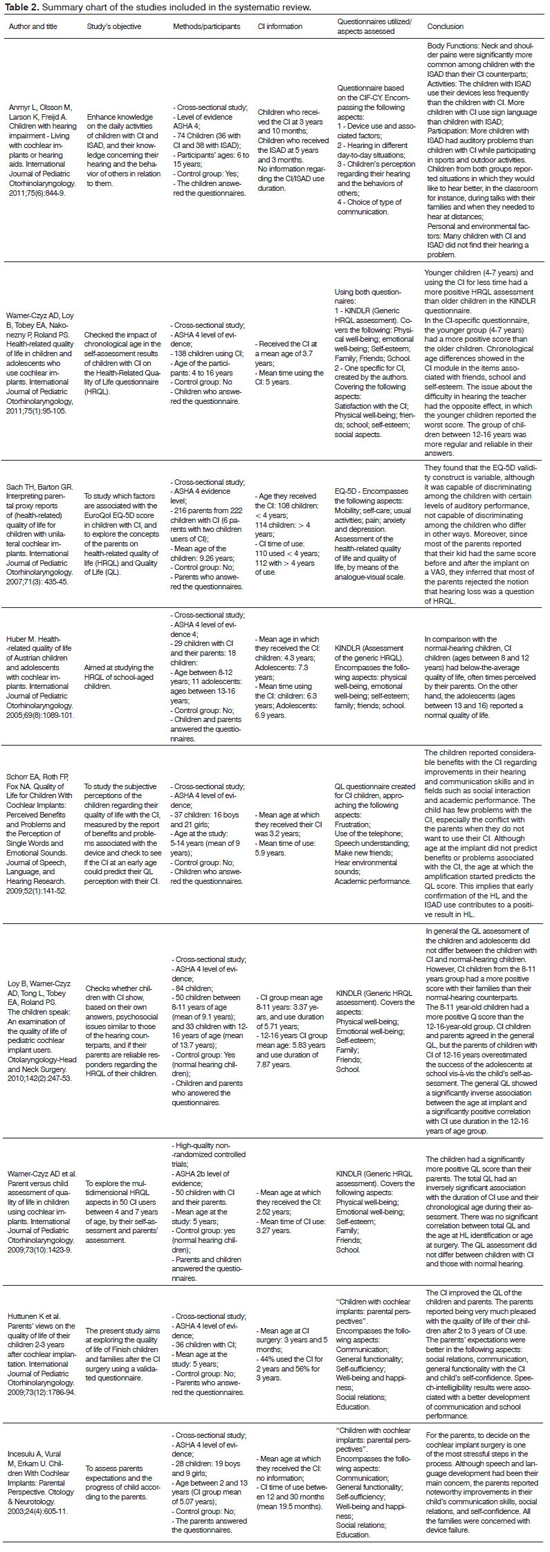

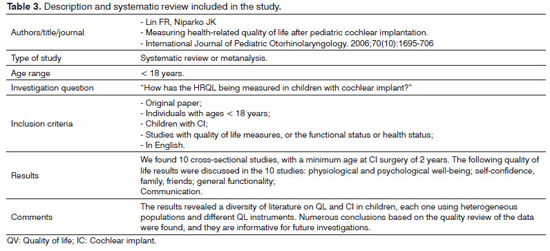

At the end, 10 papers met the inclusion criteria3,7,11,17,19-24. Of these 10 papers included in this revision, 8 were classified as cross-sectional studies3,11,19-24, one was characterized as a high quality non-randomized controlled trial7, classified as level 2b according to the ASHA criteria, and one was a systematic revision17 (Tables 2 and 3).

A systematic review is described on Table 2 with the authors' names, the year of publication, the journal chosen for publication, type of study, the age group included in the papers examined by the authors, the search string, the inclusion criteria for selecting the studies and the results found.

This set of papers was submitted to data evaluation, and the relevant information from each paper (number of participating subjects, age upon CI, duration of use, mean age of the subjects, object of the study, questionnaires used and conclusion), as well as classification vis-à-vis the degree of recommendation, gathered in tables to facilitate consultation and access during the presentation and result discussion (Table 3).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The cochlear implant (CI) surgery impact on the children and adolescents with severe and/or profound hearing loss extends to beyond the improvement in hearing and language skills, and in speech production and perception. This impact also involves other aspects of the child's daily life, such as physical, psychological and social well-being19.

Considering the interest to investigate which were the main quality-of-life aspects described in the literature and to check which factors were associated with this measure in children and youngsters using CI, this study involved a systematic survey of the literature in this field.

The results showed a difference among the studies investigated, considering the age upon evaluation, age of surgery, CI use duration, and the instruments used to assess quality of life. These results were also found in the systematic review carried out by Lin & Niparko17.

From the qualitative analysis of the studies, it was possible to notice that the main aspects of quality of life raised in the studies selected for this systematic review were: physical well-being; emotional well-being; self-esteem; family; friends; school; satisfaction with the CI; social aspects; mobility; self-care; pain; telephone use; speech understanding; hearing environmental sounds; communication; self-sufficiency; use of the devices; attitudes of the others and self-confidence.

Thus, both aspects of health-related quality of life (physical, psychological and social well-being)20 and specific aspects of this population of CI users (family, friends, school, satisfaction with the CI, telephone use, speech understanding, listening to environmental sounds and use of the devices) were investigated.

Although the generic instruments of health-related quality-of-life evaluation are much too general vis-à-vis the investigated aspects, which cannot enable the investigation of issues of particular interest for a given condition (for instance, telephone use), some studies currently show that these bear enough sensitivity, given the ample impact that the hearing loss has on the life of a child3. Another advantage of this type of instrument is the ability of being able to compare the multidimensional aspects that make it, in different groups of children20.

Moreover, currently few specific and standardized HRQL assessment tools are available for the pediatric population with hearing loss. It was only in December of 2011 that a tool intended for the assessment of quality of life in children with hearing loss was published, called "Hearing environments and Reflections on Quality of Life (HEAR-QL)"25. This questionnaire was not translated into Portuguese until the final analysis of this study.

Thus, we recommend that these two types of assessment should be used in order to perform a HRQL assessment in children with hearing loss, as complementary to the clinical results. The two instruments are needed to completely understand the CI impact instead of compartmentalizing this intervention into an auditory phenomenon only20.

In relation to the analysis of the quality-of-life measure-related factors in children and youngsters with CI, one of the evaluated aspects was the child's age upon surgery. The qualitative analysis of the studies which ran this analysis made it possible to consider that children who were submitted to surgery in earlier ages make a more positive analysis of their quality of life.

Although each study evaluated children at different ages, research in this field show that children implanted earlier reach a better auditory perception, better, incidental language acquisition and better speech inteligibility1,8. The early development of these skills can improve the children's communication with their parents and at school, thus bringing about better social performances, reflected on quality of life assessments.

As to the duration of use, of the three studies that ran this analysis, two found a positive correlation between the total HRQL score and the duration of the CI use, and those children using it longer had a more positive assessment of their HRQL. This aspect has also has been relevant in the results obtained from children26. Children using it longer and more effective may have a better speech perception and intelligibility performances; and just like the age upon implantation, the more effective communication may bring about benefits for other aspects of life.

Thirty children using CI for a period of 10 to 14 years were assessed in a prospective and longitudinal study as to their speech perception and intelligibility. The results showed that 87% of the children used the implant effectively, and after 10 years of use, 60% could speak on the telephone, and 77% developed speech intelligibility near that of their normal hearing counterparts27.

Some studies7,20,21 found a significantly inverse correlation between the child's chronological age and the HRQL evaluation, in which the younger children made a more positive classification of their HRQL than the older children. The groups of children evaluated in these studies had ages varying between 4 and 16 years and, in the three studies, the younger children had been submitted to the CI surgery earlier than the older children, and these findings can be justified vis-à-vis quality of life.

This early identification and prevention of the hearing loss may have provided for a faster and more complete acceptance, recover of hearing and, consequently, of the CI in the lives of the younger children. That is, the CI use within the children's day-to-day activities enables them to embody the device as part of themselves, instead of being something that distinguished them from their normal-hearing colleagues7.

Both for children and their parents, the speech perception results were correlated with quality of life, and these findings may indicate that their perceptions regarding the well-being of the CI users are influenced by factors that go beyond hearing and communication capacity28. Moreover, today, advances in the CI hardware, software and speech processing technology have had a direct impact on the performance and success associated with speech understanding, and such factors should be always considered, since they may in such a way impact the QL results.

As to the differences in quality-of-life evaluations among children using the CI, their parents and children with hearing, the data did not allow for conclusions in relation to these comparisons.

In some fields, such as auditory rehabilitation - where the problems are of complex and intervention cannot be done in definitive groups (control group versus case group), it is possible to include in the systematic review those studies with limited methodological characteristics, at least for the methodological standards adopted by high scientific evidence studies29. Consequently, these studies could be susceptible to a restricted analysis, but they should not be discarded.

We must consider the different ages at which the surgery was carried out, and the duration of CI use in each study must be considered a limitation, given the well-established association between the development of hearing and language skills and these variables and, therefore, the heterogeneity of these factors may result in a population with broad results vis-à-vis language skills17.

FINAL REMARKS

Further studies must be done, using HRQL assessment tools which enable result comparison among clinics and countries, and which may lead to a better understanding of the criteria used to select candidates for the surgery, the needs for rehabilitating children with CI, besides enabling access to the clinics, allowing the children with CI to develop their true potential in all aspects of their lives.

REFERENCES

1. Geers AE. Speech, language, and reading skills after early cochlear implantation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(5):634-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.5.634 PMid:15148189

2. Daya H, Ashley A, Gysin C, Papsin BC. Changes in educational placement and speech perception ability after cochlear implantation in children. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29(4):224-8. PMid:11003074

3. Huber M. Health-related quality of life of Austrian children and adolescents with cochlear implants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(8):1089-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.018 PMid:15946746

4. Davis E, Waters E, Mackinnon A, Reddihough D, Graham HK, Mehmet-Radji O, et al. Paediatric quality of life instruments: a review of the impact of the conceptual framework on outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(4):311-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0012162206000673 PMid:16542522

5. Kelsay DM, Tyler RS. Advantages and disadvantages expected and realized by pediatric cochlear implant recipients as reported by their parents. Am J Otol. 1996;17(6):866-73. PMid:8915415

6. Brouwer CN, Maillé AR, Rovers MM, Grobbee DE, Sanders EA, Schilder AG. Health-related quality of life in children with otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(8):1031-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.013 PMid:16005345

7. Warner-Czyz AD, Loy B, Roland PS, Tong L, Tobey EA. Parent versus child assessment of quality of life in children using cochlear implants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(10):1423-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.07.009 PMid:19674798 PMCid:2891383

8. Nicholas JG, Geers AE. Personal, social, and family adjustment in school-aged children with a cochlear implant. Ear Hear. 2003;24(1 Suppl):69S-81S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.AUD.0000051750.31186.7A PMid:12612482

9. O'Neill C, O'Donoghue GM, Archbold SM, Normand C. A cost-utility analysis of pediatric cochlear implantation. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(1):156-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200001000-00028

10. Huttunen K, Rimmanen S, Vikman S, Virokannas N, Sorri M, Archbold S, et al. Parents' views on the quality of life of their children 2-3 years after cochlear implantation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1786-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.038 PMid:19875180

11. Archbold S, Sach T, O'Neill C, Lutman M, Gregory S. Outcomes from cochlear implantation for child and family: parental perspectives. Deaf Educ Int. 2008;10(3):120-42.

12. Matza LS, Swensen AR, Flood EM, Secnik K, Leidy NK. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children: a review of conceptual, methodological, and regulatory issues. Value Health. 2004;7(1):79-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.71273.x PMid:14720133

13. Bess FH, Dodd-Murphy J, Parker RA. Children with minimal sensorineural hearing loss: prevalence, educational performance, and functional status. Ear Hear. 1998;19(5):339-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003446-199810000-00001 PMid:9796643

14. Wake M, Hughes EK, Collins CM, Poulakis Z. Parent-reported health-related quality of life in children with congenital hearing loss: a population study. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(5):411-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1367/A03-191R.1 PMid:15369416

15. Barton GR, Bankart J, Davis AC. A comparison of the quality of life of hearing-impaired people as estimated by three different utility measures. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(3):157-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14992020500057566 PMid:15916116

16. Eiser C, Morse R. The measurement of quality of life in children: past and future perspectives. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22(4):248-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200108000-00007

17. Lin FR, Niparko JK. Measuring health-related quality of life after pediatric cochlear implantation: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006:70(10);1695-706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.05.009 PMid:16806501

18. http://www.asha.org/Publications/leader/2005/050524/f050524a.htm#3 (acesso em 12/9/2012).

19. Anmyr L, Olsson M, Larson K, Freijd A. Children with hearing impairment-living with cochlear implants or hearing aids. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(6):844-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.03.023 PMid:21514963

20. Warner-Czyz AD, Loy B, Tobey EA, Nakonezny P, Roland PS. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who use cochlear implants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(1):95-105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.10.018 PMid:21074282

21. Loy B, Warner-Czyz AD, Tong L, Tobey EA, Roland PS. The children speak: an examination of the quality of life of pediatric cochlear implant users. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(2):247-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.045 PMid:20115983 PMCid:2852181

22. Schorr EA, Roth FP, Fox NA. Quality of life for children with cochlear implants: perceived benefits and problems and the perception of single words and emotional sounds. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(1):141-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0213)

23. Sach TH, Barton GR. Interpreting parental proxy reports of (health-related) quality of life for children with unilateral cochlear implants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(3):435-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.011 PMid:17161471

24. Incesulu A, Vural M, Erkam U. Children with cochlear implants: parental perspective. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(4):605-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00129492-200307000-00013 PMid:12851553

25. Umansky AM, Jeffe DB, Lieu JE. The HEAR-QL: quality of life questionnaire for children with hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2011;22(10):644-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.22.10.3 PMid:22212764 PMCid:3273903

26. Bakhshaee M, Ghasemi MM, Shakeri MT, Razmara N, Tayarani H, Tale MR. Speech development in children after cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(11):1263-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00405-007-0358-1 PMid:17639444

27. Beadle EA, McKinley DJ, Nikolopoulos TP, Brough J, O'Donoghue GM, Archbold SM. Long-term functional outcomes and academic-occupational status in implanted children after 10 to 14 years of cochlear implant use. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(6):1152-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000180483.16619.8f PMid:16272934

28. Clark JH, Wang NY, Riley AW, Carson CM, Meserole RL, Lin FR, et al. Timing of cochlear implantation and parents' global ratings of children's health and development. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(4):545-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182522906 PMid:22588232

29. Hyde M. Evidence-Based Practice, Ethics and EHDI Program Quality. In: Seewald RC, Bamford JM, (eds). A Sound Foundation through Early Amplification: Proceedings of the Third International Conference. Stäfa, Switzerland: Phonak AG; 2005. p.281-301.

1. Doctor in Sciences - School of Public Health of the University of São Paulo; Speech and Hearing Therapist, Specialist in Laboratory - School of Dentistry of Bauru - USP.

2. Master in Sciences School of Dentistry of Bauru - University of São Paulo (FOB-USP); Speech and Hearing Therapist.

3. Specialist in Clinical and Educational Audiology - Craniofacial Anomalies Hospital (HRAC-USP); Speech and Hearing Therapist - Hearing Impaired Patients' Association, Parents, Friends and Users of Cochlear Implants (ADAP - Bauru).

4. Specialist in Clinical and Educational Audiology - Craniofacial Anomalies Hospital (HRAC-USP); Speech and Hearing Therapist - HRAC-USP.

5. Full Professor - Department of Speech and Hearing Therapy - Dentistry School of Bauru - University of São Paulo (FOB-USP) and Coordinator of the CPA-HRAC-USP.

6. PhD in Public Health; Professor - Department of Epidemiology - School of Public Health of the University of São Paulo - FSP/USP.

Department of Epidemiology - School of Public Health - University of São Paulo (USP). Audiological Research Center - Hospital of Craniofacial Anomalies Rehabilitation - University of São Paulo - Bauru Campus.

Send correspondence to:

Marina Morettin

Rua Silvio Marchione, nº 3/20. Bauru - SP. Brazil

CEP: 17043-900. Caixa Postal: 620

E-mail: mmorettin@usp.br

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System - Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on September 26, 2012.

Accepted on November 2, 2012. cod. 10481.