Year: 2013 Vol. 79 Ed. 1 - (22º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 121 to 121

Esophageal perforation in closed neck trauma

Author(s): Agnaldo José Graciano1; Adrian Maurício Stockler Schner2; Carlos Augusto Fischer3

DOI: 10.5935/1808-8694.20130022

Keywords: blunt wounds; esophageal perforation; neck injuries.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal perforation is rare in blunt neck injuries, but it carries a 20% mortality rate. This high mortality rate is caused by delays in diagnosis because of not considering the injury in these circumstances, preventing proper treatment to be carried out before severe complications ensue.

Here, we provide an example and the basis for its recognition and management, according to data from the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

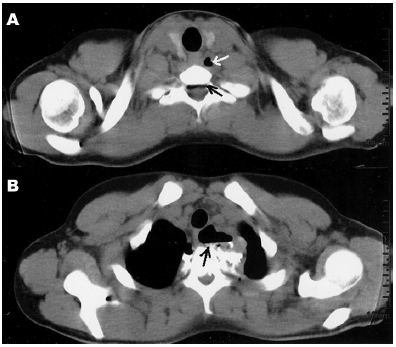

A 17 year-old male came to our clinic complaining of pain and vomits upon swallowing for about one week after having fell from a bicycle and having his body turned on its neck axis. He was assessed twice in other clinics, and was prescribed analgesics and anti-vomiting medication, without improvements. He was submitted to a CT scan, which showed neck emphysema and pneumorachis (Figure 1 A-B), and an MRI scan confirmed he also had a ligament injury between T1 and T2 and a blood workup showed mild leukocytosis. Although the gastric endoscopy did not show injuries, immediate exploratory neck surgery was indicated, which revealed a 1.5 cm esophageal rupture in the neck-chest transition area, and rupture of muscles and intervertebral ligaments. The esophagus was sutured and the neck was drained. The patient was submitted to antibiotic treatment and parenteral nutrition with resolution of the perforation, without other complications.

Figure 1. A: CT scan showing neck extraluminal air (clear arrow) and air in the spinal canal (dark arrow). B: Extensive air collection in contact with the esophageal wall.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal perforations have been increasingly seen because of a raise in the number of diagnostic and treatment endoscopies, and its incidence has been estimated to be 3.1:1000,000/year1. Today, 60% of the perforations are iatrogenic, secondary to endoscopic and neck/chest procedures, 15% are spontaneous (Boerhaave's syndrome), more commonly seen in the thoracic or abdominal portions of the esophagus, and only 2% to 15% are caused by neck trauma. Most of the trauma-induced esophagus injuries are located in the neck (57%), followed by the its thoracic and abdominal portions, caused by firearm (78.8%) or blunt weapons (18.5%) and only 2.7% are associated with blunt neck traumas2.

In blunt neck injuries, it is important to suspect of esophageal perforations in situations involving fast acceleration and deceleration associated with neck hyperextension with the esophagus being pushed against the spine.

The most common symptom is odynophagia, complained by 70% to 92% of the patients. Special attention must be given to pain, vomit and dyspnea upon deglutition (Mackler's triad) - in 25% of the patients. Although not very specific for esophageal injuries, thoracic and/or neck subcutaneous emphysema and pneumorachis (air in the spinal canal) hints at the possibility of rupture of some structure which had air3.

When there is a suspicion of esophageal perforation, complementary tests must be carried out immediately, because there is an increase in the occurrence of severe complications when the investigation and treatment happen 24 hours after the injury and, after such time, mortality may reach up to 60% in cases of late treatment.

The test-of-choice is esophagography, yielding between 90% and 100% sensitiveness. Water-soluble contrasts (Gastrografin®) are preferable, due to a lesser risk of mediastinal inflammatory reaction, more commonly associated with the use of barium contrasts. Nonetheless, its use does not detect small neck esophageal perforations in up to 50% of the cases, favoring the use of barium contrast medium in some institutions4. Stiff esophagoscopy was the second most utilized exam in a study involving 405 patients from 34 trauma centers in the US, followed by flexible endoscopy - which may be associated with esophagography in cases of suspicion of esophageal injury with an initially-normal radiographic exam, boasting up to 100% specificity5.

The most recommended initial approach is primary esophageal suture, utilized in about 80% of the cases, associated with neck drainage, antibiotic treatment and enteral or parenteral nutrition6.

FINAL REMARKS

Esophageal perforation is rare in blunt neck injuries, but it should be suspected in high-speed injuries with neck over-extension.

REFERENCES

1. Vidarsdottir H, Blondal S, Alfredsson H, Geirsson A, Gudbjartsson T. Oesophageal perforations in Iceland: a whole population study on incidence, aetiology and surgical outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58(8):476-80.

2. Asensio JA, Chahwan S, Forno W, MacKersie R, Wall M, Lake J, et al.; American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Penetrating esophageal injuries: multicenter study of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50(2):289- 96.

3. Søreide JA, Viste A. Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:66.

4. Wu JT, Mattox KL, Wall MJ Jr. Esophageal perforations: new perspectives and treatment paradigms. J Trauma. 2007;63(5):1173-84.

5. Arantes V, Campolina C, Valerio SH, de Sa RN, Toledo C, Ferrari TA, et al. Flexible esophagoscopy as a diagnostic tool for traumatic esophageal injuries. J Trauma. 2009;66(6):1677-82.

6. Sepesi B, Raymond DP, Peters JH. Esophageal perforation: surgical, endoscopic and medical management strategies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(4):379-83.

1. MD, MSc in Sciences (Otorhinolaryngologist and Head and Neck Surgeon - Hospital São José e Centro Hospitalar Unimed - Joinville - SC).

2. MD (Chest Surgeon - Hospital São José e Centro Hospitalar Unimed - Joinville - SC).

3. MD (Head and Neck Surgeon and Maxillo-Facial Surgeon - Hospital São José e Centro Hospitalar Unimed - Joinville - SC).

Centro Hospitalar Unimed - Joinville - Santa Catarina.

Send correspondence to:

Agnaldo José Graciano

Rua 3 de Maio, nº 58, sala 104. Centro

Joinville - SC. Brazil. CEP: 89201-030.

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System - Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on November 15, 2011.

Accepted on February 3, 2012. cod. 8904.

All rights reserved - 1933 /

2025

© - Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico Facial