Year: 2011 Vol. 77 Ed. 6 - (18º)

Artigo de Revisão

Pages: 799 to 804

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo without nystagmus:diagnosis and treatment

Author(s): Gabriella Assumpção Alvarenga1; Maria Alves Barbosa2; Celmo Celeno Porto3

Keywords: therapeutical approaches, diagnosis, vertigo.

Abstract:

Nystagmus tests to diagnose BPPV are still relevant in the clinical evaluation of BPPV. However, in everyday practice, there are cases of vertigo caused by head movements, which do not follow this sign in the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the turn test. Aim: To characterize BPPV without nystagmus and treatment for it. Materials and methods: A non-systematic review of diagnosis and treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) without nystagmus in the PubMed, SciELO, Cochrane, BIREME, LILACS and MEDLINE daases in the years between 2001 and 2009. Results: We found nine papers dealing with BPPV without nystagmus, whose diagnoses were based solely on clinical history and physical examination. The treatment of BPPV without nystagmus was made by Epley maneuvers, Sémont, modified releasing for posterior semicircular canal and Brandt-Daroff exercises.Conclusion: From 50% to 97.1% of the patients with BPPV without nystagmus had symptom remission, while patients with BPPV with nystagmus with symptom remission ranged from 76% to 100%. These differences may not be significant, which points to the need for more studies on BPPV without nystagmus.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is one of the most frequent vestibular disorders. Its incidence varies between 11 and 64 cases per 100 thousand inhabitants1.It predominates in the age range between 50 and 55 years in idiopathic cases2 and it is rare in childhood3.It is more frequently seen at older ages because of the degeneration of statoconia, arising from demineralization, shown by means of histopathology studies4.

According to Weider et al.5, the first to describe BPPV was Busch, in 1882. After the first description, the papers considered important were published by these authors: Adler in 1897 and Báràny6 in 1921.

As far as etiopathogeny is concerned, Schuknecht7 and Schuknecht & Ruby8 called cupulolithiasis the deposit of these particles in the posterior semicircular canal. Hall et al.9 suggested that these particles would be floating, which is called canalithiasis. Gans10 stated that everyone has an amount of free statoconia in their semicircular canals. Nonetheless, the body is normally able to totally absorb the calcium within a few hours or days, without triggering symptoms. These would be triggered when the body meolism has difficulties in absorbing calcium. In the presence of these free calcium carbonate particles in the semicircular canals coming from the fractioning of the otoliths in the utricular macula and in enough quantity to activate the nerve endings, vertigo is triggered during head movement, thus characterizing BPPV.

The most often involved semicircular canal in the BPPV is the posterior11, nonetheless, there may be otolith deposits in the lateral and anterior semicircular canals12.

Among the causes associated with BPPV, the most common are head injury (17%) and vestibular neuritis (15%). Other causes include vertebrobasilar ischemia, labyrinthitis and surgical complications from middle ear intervention and after prolonged rest. Nonetheless, most of the cases seem to be idiopatic2.

For diagnostic purposes, the positioning nystagmus investigation enables the localization of the side and that of the damaged canal and the distinction between canalithiasis and cupulolithiasis, being important to guide the most indicated rehabilitation exercises for each case, a fundamental part of treatment12.

Dix & Hallpike13 were responsible for eslishing the objective criteria for BPPV diagnosis. They described a maneuver which helps evaluate vertigo and positioning nystagmus and proposed the name of BPPV for this disorder which included this symptom and sign. These authors described that upon the maneuver, nystagmus would be triggered after a latency time, disappearing after the maneuver is repeated two or three times; nonetheless, the diagnosis of BPPV was only considered in the presence of nystagmus.

The Dix and Hallpike maneuver have a positive predictive value of 83% and negative predictive value of 52% for the diagnosis of posterior and anterior semicircular canal BPPV, and a common mistake is not to perform it in patients complaining of vertigo or dizziness14,15-16. The Brandt-Daroff test, or the turn test is used to look for lateral canal positional nystagmus12,17. In general, it is not recommended to order image complementary exams, vestibular tests, or both in patients clinically diagnosed with BPPV, unless it is uncertain or when there are other signs and symptoms in the BPPV tests17.

Nystagmus in these cases is considered important to characterize the BPPV until current days. Nonetheless, in the clinical practice, there are cases of vertigo caused by movements such as: laying down, turning from one side to the other in bed, fast head movements horizontally and bending over, without nystagmus in the Dix -Hallpike maneuaver18,19.

BPPV studies2,20-22, two systematic reviews among them2,20, approached the BPPV treatment without mentioning the diagnostic difficulty in the absence of nystagmus.As reported by Silveira & Munaro23, there is a shortage of studies on this subject. On BPPV studies2,20; in general, the patients who did not have nystagmus are taken off the study, especially when the study aims at proving treatment when the lack of this signal characterizes the study outcome.

Treatment with exercises and vestibular rehabilitation repositioning maneuvers depend on the identification of the damaged canal and are not specific for each one of them12. Upon nystagmus and detecting the semicircular canal involved, the canalith repositioning maneuver has been proven efficient (especially that of Epley for the posterior semicircular canal)1,20. Nonetheless, in the absence of nystagmus, would it be possible to diagnose and treat BPPV?

Given the aforementioned, added to the scarce publications on BPPV without nystagmus, also called subjective or atypical, this non-systematic review is fully justified and its goal is to characterize the BPPV without nystagmus, as well as the treatment approach in such situations.

METHODOLOGY

We searched for papers in the following daases: MEDLINE, BIREME, SCIELO, LILACS, PUBMED starting from the keywords which characterized the topic: BPPV, lack of nystagmus, diagnosis and treatment, in Portuguese, English and German.

The selection criteria for studies were: published between 2001 and 2009; clinical studies with adults and literature reviews with emphasis in the diagnosis and treatment of BPPV without nystagmus. Added to this review is the summary, in English of a paper in Chinese24, available at PUBMED. One of the papers corresponding to the criteria of this study25 was not found.

RESULTS

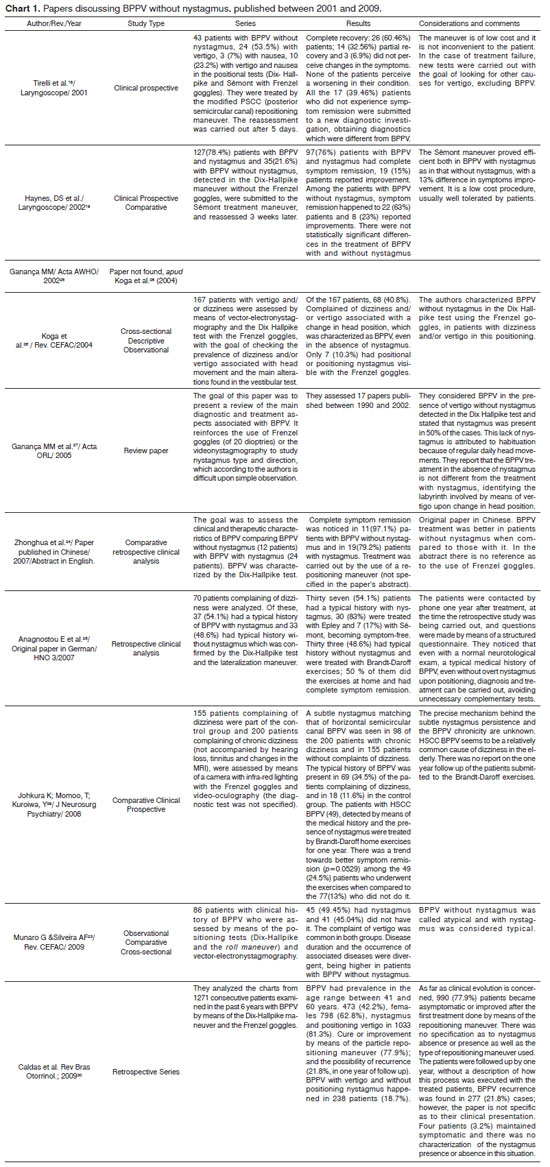

Of the ten listed papers, we found nine18,19,23-30 (Chart 1).

DISCUSSION

As we can see on Chart 1, in the studies with BPPV without nystagmus, one was a bibliography review study27, two were observational cross-sectional studies23,26, three were retrospective clinical analyses24,28,30 - one comparative24 and three prospective clinical analyses18,19,29, two of which were comparative19,29.

BPPV without nystagmus is characterized by the clinical exam in which the patients complaining of brief BPPV spells without nystagmus and/or nausea associated with changes in head position did not have positional and/ positioning nystagmus18,19,23-30.

Caovilla & Ganança31 state that the possible results from the Dix-Hallpike test in BPPV with and without nystagmus are: positive objective, when there is nystagmus associated with vertigo, positive subjective when there is only vertigo and negative in the absence of nystagmus and vertigo.

We found three probable explanations for the absence of dizziness and positioning nystagmus in head movement which would enable symptom and ocular phenomenon elimination at that time. The patients could have minimum calcium carbonate particles stuck to the cupule or floating in the affected semicircular canal, enough to cause nausea and/or vertigo, but not enough to cause nystagmus. In this situation, the affected labyrinth would be the one on the same side of the maneuver from which the patient reported dizziness seating down. Before treating the patient, the maneuver can be negative for BPPV in a first assessment and positive in another one, on the same day or in a different day. Many BPPV cases did not have positioning nystagmus or dizziness at the time of the maneuver, which does not rule out the diagnostic maneauver18,19,27.

Another explanation for the BPPV without nystagmus was proposed by Johkura, Momoo & Kuroiwa29. They perceived that among elderly citizens with chronic dizziness of unknown cause, without nystagmus in the conventional assessment using Frenzel goggles, diagnosis is very difficult. After investigating 200 elderly with dizziness, in whom they used an infrared camera and video-oculography, they found a faint positional ageotropic horizontal nystagmus, compatible with horizontal semicircular canal (HSCC) BPPV in 98 patients. It is also stressed that the mechanism of this mild nystagmus in the elderly is unknown, and they are also not eligible to make up for the balance disorder caused by this BPPV. These authors consider that the prevalence of this mild nystagmus is high and its history matches that of BPPV in the elderly, suggesting that the HSCC BPPV is one relatively common cause of chronic dizziness considered of unknown cause in the elderly.

Gans10 presents a third explanation based on a change in the calcium metabolism and the consequent non-absorption of free otoliths, which would increase their quantity in the semicircular canals and enable the triggering of vertigo upon head movement.

They did not present nystagmus in the diagnosis of BPPV in cross-sectional studies23,26 and prospective18,19,29 and retrospective24,28,30 cohorts in 9.6% to 89.7% of the patients with a mean value of 42% of the patients -, which is similar to the one found in the Ganança et al.27 bibliographic review, which considered nystagmus present in 50% of the patients.

Dix-Hallpike was the one most used in the studies18,19,23,24,26- 28,30, with Frenzel goggles18,26,27,30 for the diagnosis of BPPV, with or without nystagmus and its characteristics. It is very difficult to recognize the positioning nystagmus type and direction upon simple observation, because this ocular phenomenon is mild and short lasted. The use of the Frenzel goggles (20 dioptries) or videonystagmography (VNG) enables the proper identification of the positioning nystagmus, allowing the pinpointing of the semicircular canal involved in the BPPV. The Frenzel goggles and the VNG rule out the inhibiting effect of the eye fixation on the vertical and horizontal nystagmus, this happens because the rotational nystagmus is not inhibited by eye fixation.

The treatment of BPPV without nystagmus was carried out by means of the Epley28 and Sémont19,28 maneuvers, the Brandt-Daroff28,29 exercises and the Modified Posterior Semicircular Canal Maneauver18. Nonetheless, two studies did not mention the maneuvers utilized24,30.

As far as treatment for BPPV patients without nystagmus is concerned18,19,24,28, 50 to 97.1% of the patients (mean value of 67.64%) had remission.

In the studies19,24,28 which compared treatment results from patients with and without nystagmus, symptom remission was 17% greater among patients with nystagmus. Haynes et al.19 did not find a significant difference (13%) among patients with and without nystagmus. On the other hand, Zhonghua et al.24 stated that the patients without nystagmus had a significantly higher improvement when compared to the patients who had BPPV with nystagmus (17.9%).

In the three prospective studies, there were no similarities in the follow up of these patients. One reassessed the patients after 5 days18, another reassessed them after 3 weeks19 and the third29, after one year.

Most of the BPPV cases, with or without nystagmus responded favorably to vestibular rehabilitation physical therapy procedures. Ganança et al.27 stated that vertigo upon head position change enables the identification of the labyrinth involved in the BPPV without nystagmus. Failures can happen because of the movement of crystals to another semicircular canal, creating another BPPV variant.

CONCLUSION

BPPV without nystagmus is characterized by vertigo and/or nausea in the absence of nystagmus, especially in the Dix-Hallpike and in the Sémont, Brandt-Daroff tests or in the turn test or lateralization maneuver. Frenzel goggles with infrared camera were not used in all the patients, but they may be useful.

The treatment of BPPV without nystagmus may be carried out based on the typical history of BPPV and signs found upon physical examination, with vertigo. One should treat the side on which the signs were triggered by means of the Epley and Sémont maneuvers and the Brandt-Daroff exercises, or even, by means of the modified freeing maneuver for the posterior semicircular canal.

Symptom remission among patients with BPPV without nystagmus who were treated was of 67.64%, with a subtle difference for patients with nystagmus (13% to 17%), which suggests the need for BPPV treatment, even in patients without nystagmus.

REFERENCES

1. Maia RA, Diniz FL, Carlesse A. Manobras de reposicionamento na vertigem paroxística posicional benigna. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2001;67(5):612-6.

2. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo - a systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(6):440-5.

3. Baloh RW, Honrubia V. Childhood onset of benign positional vertigo. Neurology. 1998;50(5):1494-6.

4. Walther LE, Westhofen M. Presbyvertigo-aging of otoconia and vestibular sensory cells. J Vestib Res. 2007;17(2-3):89-92.

5. Weider DJ, Ryder CJ, Stram JR. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: analysis of 44 cases treated by canalith repositioning procedure of Epley. Am J Otol. 1994;15(3):321-6.

6. Barany R, cited by Dix R, Hallpike CS. Diagnose von Krankheitserscheinungen im Bereiche des Otolithenapparates. Acta Otolaryngol. 1921;2:434-7.

7. Schuknecht HF. Cupulolithiasis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90(6):765-78.

8. Schuknecht HF, Ruby RR. Cupulolithiasis. Adv Otorhinolaryngol.1973;20:434-43.

9. Hall SF, Ruby RRF, McClure JA. The mechanics of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol. 1979;8(2):151-8.

10. Gans R. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a common dizziness sensation. Audiology Online serial on the internet.2002 Apr. Disponível em: URL: http://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/article_detail.asp?article_id=386.Acesso em 14 dez 2009.

11. Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003;169(7):681-93.

12. Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ. Avaliação e tratamento dos pacientes com vertigem posicional paroxística benigna. In: Herdman SJ, editor. Reabilitação Vestibular, 2ª ed., São Paulo: Manole; 2002. p.447-71.

13. Dix R, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1952;61(4):987-1016.

14. Gordon CR, Zur O, Furas R, Kott E, Gadoth N. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Harefuah. 2000;138(12):1024-7.

15. Labuguen RH. Initial evaluation of vertigo. Am Fam Physician.2006;73(2):244-51.

16. Viirre E, Purcell I, Baloh RW. The Dix Hallpike test and canalith repositioning maneuver. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):184-7.

17. Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(5 Suppl 4):S47-81.

18. Tirelli G, D´Orlando E, Giacomarra V, Russolo M. Benign positional vertigo without detecle nystagmus. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(6):1053-6.

19. Haynes DS, Resser JR, Labadie RF, Girasole CR, Kovach BT, Scheker LE, et al. Treatment of benign positional vertigo using the Semont manouver: efficacy in patients presenting without nystagmus. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(5):796-801.

20. Hilton M., Pinder D. La Maniobra de Epley (reposicioamiento canalicular) para el vértigo posicional paroxístico benigno (Cochrane Revisión).The Cochrane Library: The Cochrane Daase of Systematic Reviews, 2007.

21. Van der Velde GM. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo Part II: A qualitative review of non-pharmacological, conservative treatments and a case report presenting Epley's "canalith repositioning procedure", a non-invasive bedside manoeuvre for treating BPPV. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1999;43(1):41-9.

22. López-Escámez J, González-Sánchez M, Salinero J. Meta-análisis del tratamiento del vértigo posicional paroxístico benigno mediante maniobras de Epley y Semont. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1999;50(5):366-70.

23. Munaro G, Silveira AF. Avaliação vestibular na vertigem posicional paroxística benigna típica e atípica. Rev CEFAC. 2009;11(1):76-84.

24. Zhang JH, Huang J, Zhao ZX, Zhao Y, Zhou H, Wang WZ, et al. Clinical features and therapy of subjective benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi.

2007 Mar;42(3):177-80.

25. Ganança MM. Se à manobra de Dix-Hallpike o paciente só apresenta tontura e sem nistagmo quando volta à posiçäo sentada, devo considerar como positivo para VPPB? Acta AWHO 2002;21(2) apud Koga KA, Resende BD, Mor R. Estudo da prevalência de tonturas/ vertigens e das alterações vestibulares relacionadas à mudança de posição de cabeça por meio da vectoeletronistagmografia. Rev CEFAC.

2004;6(2):197-202.

26. Koga KA, Resende BD, Mor R. Estudo da prevalência de tonturas/ vertigens e das alterações vestibulares relacionadas à mudança de posição de cabeça por meio da vectoeletronistagmografia computadorizada. Rev CEFAC. 2004;6(2):197-202.

27. Ganança MM, Caovilla HH, Munhoz MSL, Silva MLG, Ganança FF, Ganança CF. Lidando com a Vertigem Posicional Paroxística Benigna. Acta ORL. 2005;23(1):20-7.

28. Anagnostou E, Mandellos D, Patelarou A, Anastasopoulos D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with and without manifest positional nystagmus: an 18-month follow-up study of 70 patients. HNO. 2005;55(3):190-4.

29. Johkura K, Momoo T, Kuroiwa Y. Positional nystagmus in patients with chronic dizziness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(12):1324-6.

30. Caldas MA, Ganança CF, Ganança FF, Ganança MM, Caovilla HH. Clinical features of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75(4):502-6.

31. Ganança MM, Caovilla HH. Reabilitação Vestibular Personalizada. In: Ganaça MM, editor. Vertigem tem cura? São Paulo: Lemos Editorial; 1998. p.197-225.

1. MSc student in Health Sciences - Federal University of Goiás, Professor at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás.

2. PhD. Adviser at the Graduate Program in Health Sciences - Universidade Federal de Goiás, Full Professor - Nursing School - Universidade Federal de Goiás.

3. PhD. Adviser at the Graduate Program in Health Sciences - Universidade Federal de Goiás, Emeritus Professor - Medical School - Universidade Federal de Goiás.

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System - Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on June 6, 2010.

Accepted on August 11, 2010. cod. 7144.