Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 2 - (22º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 288 to 292

Fibrous displasia: Report three cases

Author(s):

Adriana L. Alves 1,

Fernando Canavarros 2,

Daniela S. A.Vilela 2,

Lídio Granato 3,

José D. Próspero 4

Keywords: fibrous dysplasia, recurrence, differential diagnostic, ossifying fibroma

Abstract:

Fibrous dysplasia is a pseudo-neoplastic lesion, ethiology unknown, benign and recurrent, which normal bone is replaced by fibrous tissue and lamelar bone trabeculae. The main differential diagnosis of the monostotic form on head and neck bones is Ossifying Fibroma which some consider another form of the same entity. The purpose of this study is to make a review of the main clinical, radiological and histopathological findings that contributes to the differential diagnosis. The recurrent behavior of Fibrous Dysplasia is essential to its surgical planning and it was also analyzed on this study. We have reported three cases followed at the ENT department of Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo evaluated based on the patients symptoms, physical exam, imaging findings and treatment. In all three cases, the diagnosis was confirmed based on histopathological findings. All of them had recurrences after surgical removal, diagnosed between first and eighth year of follow up. Due to Fibrous Dysplasia and Ossifying Fibroma similar clinical courses, the histopathological findings are essential to their differential diagnosis. The long term follow up of this pacients is necessary in order to make an early diagnosis of recurrences.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia is a benign pseudo-neoplastic damage of unknown origin. It represents about 2.5% of all bone tumors. Since it is considered a congenital defect of bone modeling, it is more frequently manifested in children and adolescents, with slow growth and tendency to stabilize after puberty, together with the skeleton. It presents high rate of recurrence, with values of about 37% in adults1. At microscopy, the presence of fibrous tissue with irregular osteoid sticks that remind us of Chinese symbols is characteristic of the pathology.

Owing to the preference of facial and cranial bones normally leading to deformities, it is a disease of special interest to Otorhinolaryngologists. Polyostotic forms in these regions determine bone leontiasis.

We described 3 cases of patients with recurrent fibrous dysplasia with diagnosis confirmed by pathology analysis.

Case Report

Case 1

Male, 9-year-old black patient, complaining of frontal acute headaches for two years, worse in the morning, sometimes followed by vomiting. The patient reported reduced visual acuity on the left. At the physical examination, the patient presented ocular globe proptosis on the left.

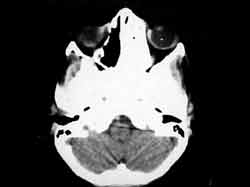

Paranasal sinuses CT scan showed irregular bone thickness in the frontal sinus on the left, ethmoidal sinus on the left and sphenoid sinus, with preserved optic nerve (Figure 1).

The patient was submitted to left frontal craniotomy to remove orbital tumor, whose pathology revealed fibrous dysplasia.

After 8 years, the patient started to present headaches again. Paranasal sinuses CT scan showed recurrence of the bone tumor with expansion into the ethmoid, sphenoid and frontal sinuses on the left.

The patient was submitted to frontoethmoidectomy and sphenoidectomy on the left to remove the tumor.

Pathology confirmed the previous diagnosis. The patient is currently on the second postoperative month and is asymptomatic and without signs of recurrence.

Case 2

Male, 8-year-old Caucasian patient, complaining of nasal bleeding and repetitive episodes of purulent conjunctivitis.

At physical examination, the patient presented hypertelorism, purulent secretion through the lachrymal sac on the left, large nasal basis and left nasal fossa filled with a burgundy tumor.

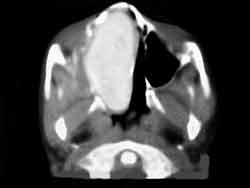

Paranasal sinuses CT scan revealed the presence of expansive mass in the left nasal fossa and ethmoid that was homogenous and with a frosted glass aspect (Figure 2).

The patient was submitted to surgery for removal of the tumor through transpalatine access.

Pathology diagnosed fibrous dysplasia.

Two years later, the patient returned with complaints of nasal obstruction associated with episodes of nasal bleeding, displacement of the ocular globe to the left and reduction of visual acuity.

At the physical examination, the patient presented hypertelorism, left eye proptosis, bulging of nasal pyramid to the left, displacement of the upper dental arch to the right and left nasal fossa filled with a burgundy tumor. Paranasal sinuses CT scan showed an expansive tumor occupying the left nasal fossa, medial wall of the left maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinuses, part of the sphenoid, medial pterygoid lamina on the left and medial and upper wall of the left orbit, reducing the orbital cavity and displacing the ocular globe to the left.

A new surgical intervention was performed with Degloving approach, and a great amount of dysplastic bone was found between the left orbit and the maxillary sinus and in the region of the ethmoid.

Pathology confirmed the previous diagnosis.

The patient is currently on the 18th postoperative month without complaints and with improved facial appearance.

Case 3

Female, 14-year-old Caucasian patient, complaining of nasal obstruction on the left for one year, followed by periorbital headache and left maxillary sinus region.

Upon physical examination, she presented hardened tumor, recovered by smooth and pink mucosa, painful upon touch, that occupied the whole roof of the left nasal fossa.

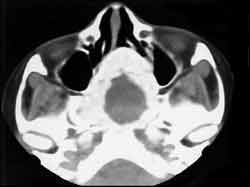

Paranasal sinuses CT scan showed the presence of an expansive mass with bone density in the region of the left nasal fossa, sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses (Figure 3).

The patient was submitted to surgery to remove the tumor, visualizing the invasion of the ethmoid, sphenoid sinuses on the left and left nasal fossa, extending up to the rhinopharynx.

Pathology diagnosed fibrous dysplasia.

On the 12th postoperative month, the patient reported complaint of nasal obstruction on the right. CT scan showed thickness and sclerosis of the sphenoid sinus walls, papyraceous laminae and vomer, with invasion into the CNS, involving the back of sella turcica and clinoid cell. She underwent a new surgery to have the tumor removed via Degloving. The pathology confirmed the previous diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia. The patient is currently on the 10th postoperative month, now asymptomatic and with normal physical examination.

Figure 1. CT scan axial sections of skull base showing dysplastic bone occupying the left nasal fossa, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses.

Figure 2. CT scan axial section of paranasal sinuses showing tumor of homogeneous density occupying the left nasal cavity with aspect of frosted glass.

Figure 3. CT scan axial section of paranasal sinuses showing tumor occupying the nasal fossae, deviating the septum and sphenoid sinuses to the right, with bone density around it and cystic content.

Figure 4. Histologic section showing dysplastic process characterized by fibrous proliferation with irregular size and shape neoformed bone sticks with variable mineralization, looking like Chinese characters.

DISCUSSION

Fibrous dysplasia is a rare, congenital, benign disease characterized by defects in bone modeling, with gradual replacement of normal bone by irregularly mineralized osteoid sticks. Some believe that it is a congenital developmental anomaly of mesenchymal tissue1.

It represents 2.5% of bone tumors and 7.5% of benign bone tumors1.

About 70% of the cases are manifested in the first decade of life, of slow growth and initially asymptomatic; they are stabilized after puberty, together with the skeletum2. They are more frequent in females and they are recurrent in about 37% of the cases in adults1.

Fibrous dysplasia is classified into two types: monostotic, when it affects one single bone or contiguous bones, and polyostotic, when affecting multiple bones. The polyostotic form, associated to the presence of hyperpigmented cutaneous spots an early puberty, in females, is called Albright's syndrome3.

The involvement of head and neck is common in about 10 to 30% of the monostotic forms and in 50 to 100% of the polyostotic forms1, 2. There are controversies concerning the preferential location. Some authors believe that it is the maxillary, followed by frontal and ethmoid sinuses1. Leed and Seaman, in 1962, identified the frontal and sphenoid bones as the most commonly affected sites4. In our cases, the most affected sinuses were ethmoid, sphenoid, frontal and maxillary.

Malignant transformation is noticed in less than 1% of the cases and this rate may reach 44% after radiotherapy1.

Fibrous dysplasia is normally asymptomatic owing to its slow growth but it sometimes manifests headache and pain.

Signs and symptoms are related to growth and craniofacial deformities, proptosis and other ocular complications are common, such as keratitis secondary to exposure, restriction of ocular movements leading to diplopia, epyphora, blepharoptosis and loss of visual field. The involvement of the sphenoid sinus may compromise the optic canal5. In only one of our cases, there was ocular compromise by extrinsic compression.

Radiologically, there are three forms of cranial fibrous dysplasia1:

· compact form: it is found in 50% of the cases. The bone is progressively replaced until it is homogenous, with an appearance of frosted glass. The lesions are found on the skull base, sphenoid body, roof of the orbit and smaller ala of the sphenoid.

· lytic form: more frequently found in the cranial bone structure and facial bones. CT scan shows irregular, radiolucent lesions surrounded by a high-density halo.

· mixed form: characterized by the presence of radiopaque areas alternated with radiolucent areas at the CT scan. This was the form observed in our three cases.

The pathology has distinguished two macroscopic presentations1:

· compact form: characterized by the presence of osteoid tissue that ossifies progressively and takes the aspect of mature bone.

· cystic form: presents one or more cavities surrounded by the alterations described above.

Microscopically, the appearance of both forms is the same. There is proliferation of fibrous tissue with progressive ossification and destruction of the affected bone. The bone trabeculate is immature, irregular in size, format and distribution, with absence of internal lamellar structure characteristic of normal bone tissue. Osteoid sticks are irregularly arranged, surrounded by osteoblasts in an arrangement that reminds us of Chinese characters (Figure 4). Pathogenesis, according to some authors, is the metaplasia of fibrous tissue.

Differential diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia is made with hyperostosis, osteoma, osteosarcoma, cordoma, hyperostotic meningioma, giant cell repairing granuloma, brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism, and ossifying fibroma. They may be differentiated by imaging techniques and, if in doubt, by pathology analysis.

Ossifying fibroma is the main differential diagnosis from the monostotic form of fibrous dysplasia, owing to their clinical, radiological and anatomic pathologic similarity.

In the head and neck, it is usually found on the mandible and maxilla but it can also be observed in the paranasal sinuses, orbit and cranial bone structures.

The process is characterized by ossification in lanes that suffer anastomosis, intertwined with fibrous proliferation. The nature of the process is still undefined, but some authors believe that it is a variant of the fibrous dysplasia.

It is normally more aggressive than fibrous dysplasia, but they are clinically identical2. Ossifying fibroma, at radiological analysis, presents a very well defined margin at CT scan, which facilitates its differentiation from fibrous dysplasia 6. Some authors disagreed and stated that all benign fibrous-bone lesions, including fibrous dysplasia and ossifying fibroma, showed well-defined margins at CT scan, hindering differentiation.

It is normally heterogeneous, and it may be uniloculated or multiloculated. It has eccentric growth but it seldom causes adjacent bone destruction.

Magnetic resonance does not help differentiation, because both present signs of low intensity in T1 and T2, being heterogeneous with contrast.

Pathology is used for the differential diagnosis of these lesions. In general, ossifying fibroma has a bone capsule that does not exist in the fibrous dysplasia 6.

Osteoid trabeculae are generally mature, with some osteoblasts in their borders, and they are important for the differential diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia bone trabeculae, normally immature6.

These histology findings are controversial since in most cases fibrous dysplasia that originates in cranial-facial bones tends to be more differentiated6. The difference between the entities is difficult because of lack of well-defined diagnostic criteria.

Treatment of both fibrous dysplasia and ossifying fibroma is surgical, aiming at complete removal owing to the possibility of recurrence and because they are not radiosensitive. Malignant transformation is rare in both cases.

Ossifying fibroma, despite its slow growth, may have a more aggressive local behavior. Fibrous dysplasia presents benign behavior and radical surgery is not always justifiable. Removable may be hindered by the absence of delimitation between the tumor and normal bone tissue, and it is usually economical to prevent mutilations. Recurrence of fibrous dysplasia is more frequent than of ossifying fibroma. Recurrence occurred in our three cases.

Closing Remarks

Fibrous dysplasia is a disease that affects young subjects. It has a benign behavior with slow and asymptomatic growth, but depending on its location, it may invade and cause compression of important skull base and orbit structures. These characteristics should not be forgotten during the surgical planning. Since it is a recurrent tumor with poorly defined limits, it is important to remove as much tissue as possible, but the surgery should be economical to avoid mutilations and functional deficits. Radiotherapy should be avoided owing to the risk of malignant transformation and because it is inefficient.

In the head and neck, differential diagnosis of the monostotic form should be done with ossifying fibroma. Owing to similar clinical and radiological behavior, pathology is essential for differentiation. The permanent follow up of patients is essential in order to diagnose early any recurrence of the disease.

References

1. Jan M, Dweik A, Destrieux C, Djebbari Y. Fronto-orbital sphenoidal fibrous dysplasia. Neurosurgery 1994;34(3):544-547.

2. Bailey BJ. Head and Neck Surgery-Otolaryngology. 2nd ed. vol. 1; Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998.

3. Paparella MM, Shumrick DA, Gluckman JL, Meyerhoff WL. Otolaryngology. 3rd. ed. vol. 2. Philadelphia: W.B. Sauders Company, 1991.

4. Mueller DP, Dolan KD, Yuh WTC.- Imaging case study of the month fibrous dysplasia of the sphenoid sinus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992;101:100-101.

5. Weisman JS, Major USAF, Hepler RS, Vinters HV. Reversible visual loss caused by fibrous dysplasia. Am J of Ophthal 1990;110(3):244-249.

6. Nakagawa K, Takasato Y, Ito Y, Yamada K. Ossifying fibroma involving the paranasal sinuses, orbit, and anterior cranial fossa: case report. Neurosurgery 1995;36(6):1192-5.

1 Post-Graduate studies in Otorhinolaryngology under course, Medical School, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.

2 Resident Physicians, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.

3 Director of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.

4 Full Professor of Pathology, Medical School, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.

Address correspondence to: Departamento de Otorrinolaringologia da Santa Casa de São Paulo

Rua Dr Cesário Mota Júnior, 112 - Pavilhão Conde de Lara - 4º andar - Tel (55 11) 3226-7235 - Fax: (55 11) 2228405

Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, presented as a free communication at the 35º Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, held in Natal, RN, on October 16 - 20, 2000.

Article submitted on September 6, 2001. Article accepted on November 20, 2001.