Year: 2002 Vol. 68 Ed. 2 - (4º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 175 to 179

Children behaviour during videonasopharyngoscopy: evaluation of 105 patients

Author(s):

Domingos H.Tsuji 1,

Natasha A. Braga 2,

Luiz U. Sennes 3,

Saramira C. Bohadana 2,

Sônia Chung 4

Keywords: children nasofibroscopy.

Abstract:

Introduction and objectives: The purpose of the present study was to report the children's behaviour during the accomplishment of the videonasopharyngolaringoscopy and the efficiency of the routine adopted by the authors for its execution. In addition, we describe our routine that leads the best execution in the pediatric population. Study design: Prospective clinical randomized. Material and Method: The study was accomplished in 105 children and adolescents, whose mean age was 7,3 years (range, 1-15 years) who underwent nasal endoscopy and or pharyngolaryngoscopy with flexible endoscope. Results: It was impossible to perform the exam in only one child (success rate- 99,04%). The occurrence of nausea did not preclude a good evaluation of the larynx and it was present in 6,7% of the cases. Among the patients enrolled in the study 24,76% of the children cried in some phases of the exam. During the endoscopic examination 42,10% of the children whose age ranged from 0 to 5 years (group I); 20,93% of the patients between 6 and 10 years (group II) and 0,00% of the patients between 11 and 15 years (group III) cried. The nasal cavity was the area more related to its occurrence, corresponding to 80% of the children that cried during the examination. Conclusion: In conclusion, using the routine adopted by the authors, the flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy is a very efficient method and the patient's tolerance is proportional to his age.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades we observed great development and popularization of endoscope diagnostic methods in the field of otorhinolaryngology. Some of the relevant methods are nasal endoscopy and pharyngolaryngoscopy, which are carried out with flexible endoscopes known as nasofibrolaryngoscope and rigid endoscopes, usually the nasal and the laryngeal telescopes.

These assessment techniques are considered first choice methods when it is necessary to carry out visual inspection of the several structures of the upper airway tract, since it is not always possible to use traditional means such as anterior and posterior rhinoscopy, direct oroscopy and indirect laryngoscopy. The examination uses a flexible endoscope that is introduced by the nasal fossae to the pharyngolaryngeal region and allows an accurate evaluation of the upper airway tract including the endonasal structures, the velopharyngeal seal, tubae ostium, palatine and lingual tonsils, hypopharyngeal structures and all levels of the larynx1. Besides enabling static evaluation of the structures, nasopharyngolaryngoscopy makes it possible to analyze functional activities during speech, cry, and swallowing movements, which are key to patients with neuromotor disorders such as pharyngolaryngeal palsy and psychosomatic dysfunctions2,3,4.

The easiness to perform nasopharyngolaryngoscopy in adults makes it a commonly used method for this age. Nevertheless, its performance in children is not always simple, mainly because of its several difficulties resulting basically from lack of understanding, support and intolerance of these patients in face of the distress caused by the procedure. Therefore, the literature does not have relative and precise consensus about the indication of this examination in pediatric patients, especially about the right time to carry out the examination. This time may be postponed up to 6 months even in cases of persistent dysphonia 5.

In face of that, the authors found convenient to develop a study with its main purposes as follows:

1) To describe the routine and technique used by the authors and to evaluate efficiency in performing it;

2) To observe children's behavior during several steps of the performance of nasopharyngolaryngoscopy under topical anesthetic drugs on the nasal mucosa, with no administration of any sedatives; and

3) To determine the anatomical regions which are closely related to the uneasiness caused by the process.

MATERIAL and METHOD

Material

The present study was carried out based on the evaluation of the reaction of 105 children and teenagers (range 1-15 years) that underwent nasal and/or pharyngeal endoscopy in the endoscopy care unit of a private otorhinolaryngology clinic. All patients were referred to the examination by other doctors. Therefore, the investigator did not have any previous professional nor personal connection with the examined patients.

Tools

All endoscopies were carried out by the same investigator (DHT), who used a flexible endoscope of the brand Machida; model ENT-p III, with 3.2 mm diameter. This device was connected to a Panasonic GP-KS152 micro camera using a source of light Xenon Wite Lite, and the images acquired were recorded in a Panasonic VCR.

Preparation of the patient

The patient was requested to fast for 2 or more hours before the examination. All patients were escorted by their respective responsible guardians during the steps of the procedure. Topical anesthetic drug used in children was as follows: 2% lidocaine, with a 1:10,000 adrenaline concentration. This solution was applied in the nasal mucosa in two steps; first application between 5 and 7 minutes before the second application that was applied almost simultaneously at the beginning of the examination. The application was made by only one female professional who was highly skilled in dealing with children. It was made with a spraying bottle originally used to apply topical corticoid drugs. Patients were instructed to wait outside the examination room between the applications. The professional gave a brief explanation about the anesthetic drug administration at each step, showing the bottle containing medication and the spray that would be used in the nasal fossae; next, she placed a small amount of the drug on the patient's hand and whenever possible on the escort's hand.

After the second application, the doctor requested the patient's escort to provide a brief background on the need of the endoscopy, and then defined the major segment of the upper airways to be examined. Still, at this moment the doctor gave a brief explanation about the technique used, explaining to the patient's escort that the procedure normally does not cause any injuries or significant pain, but it might be uncomfortable enough to demand his/her support to refrain unexpected movements of the child. Next, immediately before the examination, additional information was provided to the child to show the device with the light beam on. At this moment, the doctor gently touched the child's arm or face with the device. If the child was too fearful, refusing to have even this first introduction to the device, the doctor touched the hand or arm of the patient's escort trying to show the device is safe and offers no risks. Then, if the child's age allowed, the doctor proceeded to a quick explanation on the examination itself. The information content, however, varied according to patient's level of understanding.

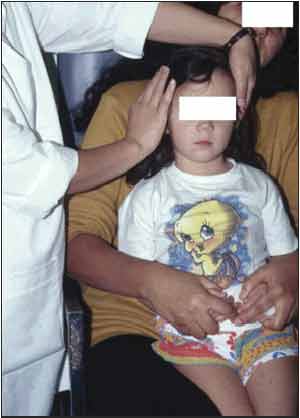

All examinations were carried out with the patient in the sitting position. Children younger than 8 year old were placed on the lap of his/her escort, which were oriented to immobilize the child's arms and legs. The doctor's assistant always immobilized the head of the patient (Figure 1). Children older than 10 years old were instructed to sit alone, having their heads gently immobilized by the assistant, only if necessary: for example, if they had any rejection movement.

If the objective of the examination was to evaluate rhinopharynx or pharyngolaryngeal region, the practitioner introduced the device through only one of the nasal fossa. Generally, the practitioner chose the apparently larger opening. Nevertheless, if it was not evident, the endoscope was introduced in one of the sides, and if any difficulty occurred during the process, the side was changed to prevent pain sensation. If the indication for the examination was due to nasal complaints, with suspicion of rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, epistaxis, polyposis and others, the endoscope was introduced bilaterally.

Patient's behavior

Child's cry was considered evident signal of emotional or physical distress, and its occurrence was evaluated in the pre-examination step (entrance in the room, first and second spray application) and during the examination itself. The anatomic part that generated such distress was described. For data analysis, patients were subdivided into three groups according to their age: Group I (0-5 years) Group II (6-10 years) and Group III (11-15 years).

Figure 1. Position adopted to restrain the child using child's mother hand and the assistant during flexible endoscopy.

RESULTS

The age of the 105 patients ranged from 1 to 15 years, and the mean was 7.3 years, with standard deviation of 3.72 years. All patients were escorted by their guardians with 92.3% of them being the patient's mother. In the total number of patient's analyzed in this study we were not able to carry out the procedure in only child (1 year old) due to agitation and lack of collaboration from the child and his/her escort. Therefore, these figures demonstrated that the performance of the examination was successful in 99.04% of cases. The presence of crying according to age, on the two steps of the procedure (pre and during exam) is explained in Tables 1 and 2.

Every time the reason for patient's referral to endoscopy was nasal complaints, the examination was carried out in both cavities, except in case of septum deviation that hindered the introduction of the device. This was the site with higher prevalence of crying (20 children, or 80% of the total 25 that cried during this step of the examination). This, however, did not make it impossible to have good view of the pathologies or anatomic structures. The larynx was examined only if necessary in a total of 44 children (42%), and not events were reported.

The occurrence of nausea did not prevent good evaluation of the larynx, and it was present in only 7 cases (6.66%), even without the use of anesthesia in the oropharyngeal region. Out of the total of 105 patients assessed in this study, 26 children (25%) cried in some moment of the procedure (including the pre exam and the exam steps) in. In the 20 children that cried after the device was introduced in the nose, 15 cried until the endoscope reached the rhinopharynx, and it decreased for 3 children until the end of the examination. Only two children began to cry after the device reached the rhinopharynx, and only one cried until the end of the procedure.

Table 1.

Table 2.

DISCUSSION

In adults, there is a consensus on indicating nasopharyngolaryngoscopy every time the otorhinological clinical picture requires the visualization of inaccessible structures through conventional methods (anterior and posterior rhinoscopy and indirect laryngoscopy). The same cannot be said about its indication for children, primarily due to difficulties to carry out this kind of examination at this age range. Such difficulties are basically lack of understanding and cooperation before and during the examination. Many times they force the doctor to postpone the examination and it might be improper management since it also delays the diagnosis. 4,5,6,7 On the other hand, it is essential to point out that not always the examination is innocuous as described in the literature 8,2,9. Therefore, the practitioner in charge should be thoughtful and careful in assessing the actual need for the procedure; distressing sensations such anxiety, fear, pain and nausea are key aspects that should not be neglected and might prevent the performance of the examination.

Because nasofibrolaryngoscopy is considered an examination that is easily performed and relatively comfortable for the patient, some authors mentioned that they do not use anesthetic drugs as part of their routine 1,8. Nevertheless, it is likely to find in the clinical practice that the level of tolerance during the procedure is quite variable and in some rare situations it is totally impossible to carry out the examination even in adults. This rejection as we have mentioned above, should be due to factors such as nausea, anxiety, fear, tactile distress and pain, which are maximized by anatomical changes such as narrow nasal cavities that makes it difficult to introduce the device and that are increasingly prominent in pediatric patients. These events make the success of the examination total unpredictable at this age range. Therefore, the authors decided to set a work routine with the purpose of improving examination efficiency and to mitigate failure rates in high demand services. The key steps used in the procedure routine were as follows:

1) Topical anesthesia and vasoconstriction drugs in all patients, except when contraindicated;

2) The help of the patient's escort to control children under 8 years of age;

3) Detailed explanation of the process to the child and his/her escort:

4) An assistant to restrain the head of the child; and

5) The examination is carried out by a skilled practitioner, specifically focused on symptom complaints.

The results found in this study, in which the success of the examination was reported in 99.04% of the patients, clearly proved that this set of measures adopted as a routine reached the desired results. In this study 24.76% of the children cried in some step of the examination. In both the pre exam and exam steps this event (crying) was inversely proportional to age, in other words, younger children demonstrated higher level of intolerance than older ones. This is certainly related to emotional immaturity of younger patients and due to the difficulty to introduce the device through narrow anatomical spaces.

The fact that some children cried early in the pre-exam step should be interpreted as the influence of emotional factors, such as fear and anxiety in face of the unknown, which are aspects that cannot be neglected. Still, cordiality and the explanation of the process to the patient and his/her escort helped to mitigate the problem. The increased frequency of crying during the introduction of the device through the nasal fossae (80% of the children cried during this step of the examination) is an indication that this is the region that generates higher level of distress for the child during the procedure. Therefore, topical anesthetic and vasoconstriction drugs are essential to mitigate the pain and distress, and consequently to increase the tolerance of the pediatric patient and the chances of the practitioner to carry out a successful endoscopy. On the other hand, contrary to what the authors expected, relevant nausea did not occur during the introduction of the device through pharynx and this made it possible to carry out static and dynamic inspections in all dysphonic patients without the need of pharyngolaryngeal topical anesthetic drug.

Assuming that the cry, in this case, is a signal of great distress that certainly would prevent spontaneous cooperation of the child, the authors considered that to restrain the child with the help of his/her escort or the practitioner's assistant is essential to prevent any injury of the anatomical structures, as well as damage of the piece of equipment. The data on Table 2 demonstrate that during the examination 42.10% of the children (range 0-5) and 20.93 of the children (range 6-10) cried. This fact led to the conclusion that from a practical point of view, all patients ranging from 0- 5 years should be restrained. Otherwise, success would not be achieved in almost half of the procedures carried out at this age group. In current practice, the authors chose to restrain children under 8 years of age since it was a facility they were referred to by other practitioners. This demanded great efficiency on our part to get the diagnosis. Conversely, in a conventional outpatient facility in which the doctor has increased personal connection with the patient, it is possible to decide initially to perform the examination with spontaneous collaboration of children older that 6 years, since according to our data only 1/5 of them would cry.

In children with low level of tolerance it is essential to perform the examination quickly and objectively, sometimes giving the impression that the ability to obtain the correct diagnosis could be affected. However, this can be compensated reviewing the images with "play-back" and slow-motion fast forward resources of the images in the VCR. Therefore, in our opinion the use of a set of equipment capable of generating and recording images with good quality is of utmost importance to carry out such examination.

In general, the performance of nasopharyngolaryngoscopy in pediatric patients is essential in several cases of clinical practice. Nevertheless, the tolerance of these patients to the procedure is considerably lower than that of adults, thus demanding careful and thoughtful indication.

CONCLUSION

The routine to perform nasofibrolaryngoscopy the authors adopted demonstrated high level of success. Children younger than 5 years of age revealed higher level of intolerance to the procedure. It made us conclude that they should be routinely restrained by their escorts or by the practitioner's assistant. Since nasal cavity is the part under major distress during the introduction of the device we recommended the use of topical anesthetic and vasoconstrictor drugs whenever possible.

REFERENCES

1. Hocutt J, Corey G, Rodney W. Nasolaryngoscopy for family physicians. AFP 1990; 42(5): 1257-1268.

2. Gray S, Smith M, Schneider H. Voice disorders in children. Pediatric Clinics of North American. 1996; 43(6): 1357-1385.

3. Handler S. Direct laryngoscopy in children: Rigid and flexible fiberoptic. Ent J 1995;74(2):101-105.

4. Kauffman I, Lina-Granade G, Disant F. La dysphonie chronique de l'enfant. Mise au point à la lumière d'une série perssonnelle de 64 cas. Pediatrie 1992;47:313-319.

5. Papsin B, Pengilly A, Leighton S. The developing role of a pediatric voice clinic: a review of our experience. The J Laryngol Otol 1996;110:1022-1026.

6. Rosen C, Anderrson D, Murry T. Evaluating hoarseness: Keeping your patient's voice healthy. Am Fam Physician 1998;57(11):2775-2782.

7. Sarfati J, Auday T. Evolution des dysphonies bénignes de l'enfant. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol 1996;117(4):327-329.

8. Olina M, Policarpo M, Aluffi P. Indicazioni e metodiche della fibroscopia rinofaringolaringea in età pediatrica. Minerva Pediatr 1996;48:341-343.

9. D'Antonio L, Chait D, Lotz W, Netsell D. Pediatric videonasoendoscopy for speech and voice evaluation. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg 1986;94(5):578-583.

1 Assistant, Ph.D., Discipline of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clinicas, Medical School of University of São Paulo, USP.

2 Ph.D., Otorhinolaryngologist, Medical School, USP.

3 Ph.D., Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, USP.

4 Otorhinolaryngologist graduated by Medical School, USP.

Study carried out by the Service of ENT Endoscopy, Hospital Paulista - São Paulo/ SP

Address correspondence to: Domingos H. Tsuji - Rua Peixoto Gomide, 515, cj. 145 - Cerqueira César CEP 01409-001 Sao Paulo - SP - Tel (55 11) 251.5504 Fax (55 11) 287.8230 - E-mail: dtsuji@attglobal.net

Article submitted on October 22, 2001. Article accepted on January 10, 2002.