Year: 2003 Vol. 69 Ed. 2 - (14º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 235 to 240

Analysis of the main etiology of hearing loss at "Escola Especial Anne Sullivan"

Author(s):

Suzana B. Cecatto[1],

Roberta I. D. Garcia[1],

Kátia S. Costa[1],

Tatiana R. T. Abdo[1],

Carlos E. B. Rezende[2],

Priscila B. Rapoport[3]

Keywords: hearing loss, deafness, child, etiology.

Abstract:

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine the etiology of hearing loss in students of "Escola de Ensino Especial Anne Sullivan" at São Caetano do Sul to make a comparison of the results with the literature. Methods: Retrospective study: we analyzed the medical history of 131 students in 2001, including the familiar anamnesis, otorhinolaryngological, psychological and audiological examination. Results: In the group, 67 (51%) were males and 64 (49%) females; 99% showed sensorineural hearing loss, 65% classified as profound. Etiological factors: in 24% no cause of hearing impairment could be determined; rubella was found in 22% of the children. The majority of the children had the suspicion and the diagnosis within 12 months old. Conclusions: The undefined etiology was the main finding, followed by congenital rubella. The diagnosis has to be made between 12 and 30 months.

![]()

Introduction

Hearing loss in children has a world prevalence of 1.5/1,000 live births, ranging from 0.8 to 2/1,000. It may be classified as sensorineural, conductive or mixed, uni or bilateral; symmetrical or asymmetrical; syndromic or non-syndromic, congenital, peri or post-natal; genetic or non-genetic; pre-lingual, peri-lingual or post-lingual. According to the Bureau International D' Audiophonologie (BIAP), hearing losses are classified as mild (20 to 40 dBHL), moderate (40 to 70 dBHL), severe (70 to 90 dBHL) and profound (over 90 dBHL). (1,2,3)

Early detection and rehabilitation are essential for speech and language development and other cognitive functions during school age. In addition, studies showed the existence of a critical period in the first years of life for speech acquisition. The absence of auditory stimulation during childhood can prevent the total development and maturing of central auditory pathways2, 3.

The present study analyzed the main causes of hearing loss among students of the special school for hearing and visually impaired children Anne Sullivan, located in São Caetano do Sul, and compared the data with those obtained in the international literature.

Material and Method

The municipal school Anne Sullivan teaches and stimulates children who has hearing and visual impairment, promoting literacy and social integration by teaching LIBRAS (Brazilian Sign Language) up to high school level. We conducted a retrospective study using the analysis of medical charts of all students who were enrolled in the school in the year 2001. We applied a protocol that gathered detailed information about family history, investigation of mothers' obstetric history, including gestation, delivery and other events, speech and hearing assessment and psychological profile, complete ENT examination and development and interaction of the patient and the family with society. In addition to such information, we studied the data from medical and speech and hearing assessments conducted at the time of the hearing loss suspicion up to confirmation with objective diagnostic exams.

We assessed the determinant causes and the contributing factors to hearing loss, gender distribution, age at suspicion and diagnosis, as well as degree of loss (chart 1).

Results

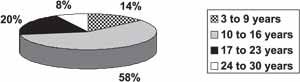

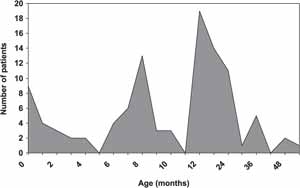

One hundred and thirty one patients were examined, being 67 male (51%) and 64 female subjects (49%). As to age, 14% of the cases were aged 3 to 9 years (19 children), 58% were aged 10 to 16 years (75 children), 20% were aged between 17 and 23 years (26 students), and 8% were aged 24 to 30 years (11 students) (Graph 1).

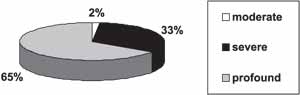

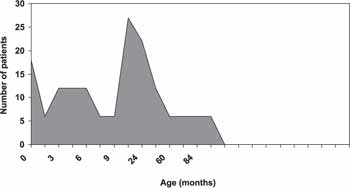

Sensorineural loss was the most frequently found, amounting to 99% of the cases. As to severity, 65% of the cases (85 students) had profound loss, 33% (44 students) had severe loss, and 2% (2 cases), moderate (Graph 2). There were no cases of mild loss.

Upon analyzing data concerning the identifiable causes, we compiled them in Table 1. Undefined etiology reached 25.2% of the cases and congenital rubella was found in 23.6%.

About 19.8% of the students (26 cases) presented multiple factors in the anamnesis comparing to pre and peri-natal periods (Table 2).

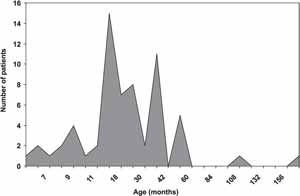

As to age at hearing loss suspicion, we observed two peaks, from 8 to 10 months and from 12 to 24 months of age. The diagnostic confirmation was made at 12 to 30 months in most of the children (Graphs 3 and 4) through the conduction of Brainstem Evoked Response Audiometry (BERA).

All studied children had fitted hearing aids. About 20% of the students (27 cases) had had the hearing aid for approximately 1 year after the diagnosis; 17% of the patients (22 cases) after 2 years and 14% of the students (18 cases) were fitted hearing aids when they were diagnosed (Graph 5).

Chart 1. Protocol - Hearing loss - Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University ABC

1. Name

2. Age

3. Gender

4. Type of hearing loss: sensorineural

conductive

mixed

5. Level: mild

moderate

severe

profound

6. Bilateral / Unilateral

7. Pregnancy/Delivery/Events

8. Causes:

a. Hereditary / congenital

b. Pre-natal: rubella / toxoplasmosis / syphilis / cytomegalovirus / herpes / abortion drugs / ototoxic drugs / measles

c. Peri-natal: hypoxia / prematurity / hyperbilirubinemia / delivery trauma / ototoxic drugs / noise

d. Post-natal: repetitive otitis / measles / meningitis / mumps / encephalitis / ototoxic drugs / head trauma / acoustic trauma / sepsis

9. Family history:

10. Age of suspicion:

11. Age of confirmation: Method:

12. Age of intervention:

13. Use of hearing aid:

14. Predominant type of communication:

15. Complete ENT examination:Table 1. Etiology of the hearing loss

Table 2. Pre-natal and peri-natal associated factors.

Graph 1. Age

Graph 2. Level of hearing loss.

Graph 3. Age of diagnostic suspicion.

Graph 4. Age at diagnostic confirmation.

Graph 5. Average interval from diagnosis to hearing aid fitting.

Discussion

According to Walch et al. (1), the history collected from parents about hereditary causes, pre, peri and post-natal episodes for the hearing loss cause is the most efficient method to try to define the hearing loss etiology of children. Similarly to our protocol, the history should include data about infections and use of drugs during pregnancy, data about birth (weight, asphyxia, hyperbilirubinemia), behavior and development of the child and the family status. In general, the cause can be classified into hereditary, acquired or unknown.

In many situations, even after a careful investigation, the precise hearing loss etiology can not be defined, as shown by Niehaus et al. (4) after the review of the literature from 1953 to 1995. Walch et al. (1) (44 % of the children with undefined cause) and Lima et al. (33 %) also found the same diagnostic difficulty.

In our retrospective study, the undefined etiology was the most frequent finding, amounting to 25.2% of the cases, confirming the described studies5. It is evident that in a significant number of hearing loss cases classified as of unknown etiology, they should in fact be cases of recessive heredity or even the result of subclinical virus infections, such as for example, cytomegalovirus 6.

Genetic and immune tests and liver and thyroid function tests should be required to reduce the large number of hearing losses classified as of unknown origin. High resolution computed tomography contributes to the diagnostic investigation, since it can detect 8 to 20% of the cases of ear malformation resultant from insults during the final gestational trimester1.

Congenital rubella is the main pre-natal cause of hearing loss owing to its teratogenic effects. The fetus is especially vulnerable to the effects of the virus in the first trimester of the gestation, which usually causes the triad of manifestations: congenital cataract, deafness and cardiac malformations1, 7. We realized in our study that congenital rubella amounted to 23.6% of the cases and it was the most expressive detectable cause of hearing loss, confirming the studies already developed in other developing countries5, 8, 9, 10, 11.

Other relevant etiologies were the association of pathogenic factors (19.8%), such as those described in Table 2 and meningitis was the most significant sensorineural post-natal etiology (Table 1). The incidence of meningitis varies in the literature from 6 to 22% 1, 5, 12, 13, 14, 15. Our study revealed 8.4% of relevance. Losses can be uni or bilateral, ranging from moderate to profound. The main pathogens involved are Meningococcus, Pneumococcus, Hemolytic B Streptococcus and Haemophylus influenzae.

The excessive use of ototoxic drugs, especially aminoglycoside antibiotics for the treatment of bronchopneumonia and enterocolitis can determine sensorineural hearing loss at expressive indexes. In our study, it amounted to 3% of the cases. Other antimicrobial agents could be also employed, but with fewer harmful effects16, 17, 18, 19.

Considering such factors, it is observed that some of the main causes of hearing loss in children such as rubella, meningitis and ototoxicity can be prevented. Using simple measures, such as vaccination programs, appropriate pre-natal guidance, and further information to healthcare professionals about prescription of ototoxic drugs, we can have prophylaxis of hearing loss.

Consanguinity did not show statistically significant incidence (2.3%), differently from the studied literature in which it occupies a highlighted position, especially in developed and Arabian countries20, 21, 22. Researchers believe that over 60% of the congenital cases are caused by genetic factors. In addition, a fraction of the post-lingual hearing loss also has genetic origin. Moreover, many studies estimate that one third to half of the human beings present a heredity component and, possibly, an associated genetic mutation1, 23.

Despite the low incidence in our study (1.5%) of repetitive otitis, if they are not early diagnosed and treated, they can compromise the cognitive development of the child24.

Hearing loss in children and adults is still a significant public health problem in Brazil, not only owing to its prevalence but also to the devastating consequences of late diagnosis and treatment.

Early detection became a priority in the United States since 1990, in which the diagnosis of hearing loss was considered ideal below 12 months of age, according to the document Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. (2,3) The Joint Committee for Infant Hearing (1994) and the European Consensus of Milan (1998) considered the age of three months as the ideal time for diagnosis. In the United States, the center Marion Downs National Center for Infant Hearing has especially dedicated to conducting universal screening in all newborns25. The purpose of such efforts is to provide to the child early rehabilitation and language and communication development.

The Council of the National Health Institute of the United States, in 1993, recommended audiological screening to all children admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit and to all children aged below 3 months using otoacoustic emissions (EOA) as initial exam, followed by BERA if EOA are abnormal1, 2, 3, 26, 27, 28.

Even though implying high cost, the screening methods are highly sensitive and non-invasive, in addition to enabling early detection of hearing loss. However, hearing loss early detection in developing countries has been inappropriate and delayed1, 5. In our study, we observed that the age in which patients suspected of hearing loss had two peaks: 8 to 10 months and 12 to 24 months, which is too late a phase to provide the appropriate development to children in the society. In addition, the diagnosis was confirmed by objective tests (BERA) only between 12 and 30 months of age in most children.

Unfortunately, we know that in Brazil there is no universal neonatal screening program in all hospitals and public maternity settings. A large percentage of pregnant women have no access to efficient pre-natal follow up.

The prevention of deafness has been proven to cost less than its treatment (hearing aid fitting or cochlear implant). In addition, the rehabilitation of these children to obtain auditory process development and social interaction is much more costly and demanding to the healthcare field than prophylaxis.

As to the period of hearing aid fitting, most students (20%) obtained the hearing aid only 1 year after the diagnostic confirmation of hearing loss. There were cases in which it took them 5 to 10 years to get the hearing aid. This fact can be explained by economic difficulties to buy and maintain the hearing aids by less privileged families.

All such data are certain to cause some indignation, especially when we realize that the most common cause of acquired hearing loss (congenital rubella, use of ototoxic drugs, meningitis, etc.) could be prevented, but in developing countries this is rarely done, as seen in our study. Another example is that in the Public Health system in Brazil sometimes the hearing aids distribution service is poor, flawed and slow.

Owing to the high percentage of unknown hearing loss causes, we suggest the development and application of a detailed questionnaire for healthcare institution to minimize these figures, followed by the conduction of early objective tests considering the potential impairment. Awareness of parents and professionals is essential (teachers, pediatricians, otorhinolaryngologists) for the children to be referred as early as possible to specialized institutions.

Conclusion

The hearing loss unknown etiology was the most representative one in the sample, followed by congenital rubella. Most of the acquired causes observed in students of the special school Ana Sullivan, as well as in Brazil, can be prevented. Currently, diagnosis and treatment (hearing aid fitting) are too late and do not enable development of the appropriate auditory processing of children.

References

1. Walch C, Anderhuber W, Köle W, Berghold A. Bilateral sensorineural hearing disorders in children: etiology of deafness and evaluation of hearing tests. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;53:31-8.

2. Brookhouser PE, Grundfast K M. In: Cummings CW et al. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: ed. Mosby; 1998. p.504-34.

3. Stelmachowicz PG, Gorga MP. In: Cummings CW. et al. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: ed. Mosby; 1998. p.401-17.

4. Niehaus HH, Olthoff E, Kruse E. Früherkennung und hörgerätversorgung unilateraler kindlicher schwerhörigkeiten. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol 1995;74:657-62.

5. Silveira JAM. Estudo da deficiência auditiva em crianças submetidas a exames de potenciais evocados auditivos. Etiologia, grau de deficiência e precocidade diagnóstica. [Tese de Doutorado] Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1992.

6. Lagasse N, Dhooge I, Govaert P. Congenital CMV-infection and hearing loss. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 2000;54(4):431-6.

7. Niedzielska G, Katsha E, Szymola D. Hearing defects in children born of mothers suffering from rubella in the first trimester of pregnancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;54:1-5.

8. Silva AA, Maudonnet O, Panhoca R. A deficiência auditiva na infância. Retrospectiva de dez anos. ACTA AWHO 1995;14(2):72-5.

9. Kadoya R, Ueda K, Miyazaki C, HidayaY, Tokugawa K. Incidence of congenital rubella syndrome and influence of the rubella vacination program for schoolgirls in Japan, 1981-1989. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148(3):263-8.

10. Schluter WW, Reef SE, Redd SC, Dyklwicz CA. Changing epidemiology of congenital rubella syndrome in the United States. J Infect Dis 1998;178(3):636-41.

11. Hinman AR, Hersh BS, Quadros CA. Rational use of rubella vaccine for prevention of congenital rubella syndrome in the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica 1998;4(3):156-160.

12. Jayarajan V, Rangan S. Delayed deterioration of hearing following bacterial meningitis. J Laryngol Otol 1999;113:1011-14.

13. Yeat SW, Mukari SZ, Said H, Motilals R. Post meningitic sensorineural hearing loss in children - alterations in hearing level. Med J Malaysia 1997;52(3):285-90.

14. Drake R, Dravitski J, Voss L. Hearing in children after meningococcal meningitis J Paediatr Child Health 2000;36(3):240-3.

15. Kapoor RK, Kumar R, Misra PK, Sharma B, Shukla R, Dnivedee S. Brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) in childhood bacterial meningitis Indian J Pediatr 1996;63(2):217-25.

16. Marlow ES, Hunt LP, Marlow N. Sensorineural hearing loss and prematurity Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2000;82:F141-4.

17. Sone M, Schachern P.A, Paparella MM. Loss of spiral ganglion cells as primary manifestation of aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Hear Res 1998;115(1-2):217-23.

18. Minja BM. Etiology of deafness among children at the Buguruni school for deaf in Dar es Salaam, Tanzânia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1998;42(3):225-31.

19. Borradori C, Fawer CL, Buclin T, Calame A. Risk factors of sensorineural hearing loss in preterm infants. Biol Neonate 1997;71(1):1-10.

20. Lui X, Xu L, Zhang S, Xu Y. Prevalence and aetiology of profound deafness in the general population of Sichuan, China. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107(11):990-3.

21. Zakzouk S. Consanguinity and hearing impairment in developing countries: a custom to be discouraged. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116(10):811-6.

22. Vartiainen E, Kemppinen P, Karjalainen J. Prevalence and etiology of bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment in a Finnish childhood population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1997;41(2):175-85.

23. Zakzouk SM, Al-Anazy F. Sensorineural hearing impaired children with unknown causes: a comprehensive etiological study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2002;64(1):17-21.

24. Ruben RJ. Persistency of an effect: otitis media during the first year of life with nine years follow-up. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;49:S115-8.

25. Ribeiro A, Castro F, Oliveira P. Surdez Infantil. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 2002;68(3):417-23.

26. Parving A. The need for universal neonatal hearing screening - some aspects of epidemiology and identification. Acta Paediatr Suppl 1999;432:69-72.

27. Isaacson G. Universal newborn hearing screening in an Inner-City, managed care environment. Laryngoscope 2000;110:881-94.

28. Eden D, Ford RPK, Hunter MF, Malpas TJ, Darlow B, Gourley J. Audiological screening of neonatal intensive care unit graduates at high risk of sensorineural hearing loss. N Z Med J 2000;113:182-3.

1 Resident physicians, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University ABC.

2 Otorhinolaryngologist, Hospital Estadual Santo André.

3 Physician, Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University ABC and Hospital Estadual Santo André.

4 Faculty Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University ABC.

Affiliation: Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, University ABC - Hospital Estadual Santo André - SP

Address correspondence to: Suzana Boltes Cecatto - Rua São Paulo, 2484 - São Caetano do Sul - São Paulo - CEP 09541-100

e-mail : suzanacecatto@yahoo.com.br

Article submitted on February 03, 2003. Article accepted on March 27, 2003.