Year: 2003 Vol. 69 Ed. 1 - (22º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 131 to 135

Malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa: literature review and report of two cases

Author(s):

Roberto E. S. Guimarães,

Helena M. G. Becker1,

Carlos A. Ribeiro,

Paulo F. B. T. Crossara,

Luís R. A. Brum,

Mônica M. O. Melo

Keywords: melanoma, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses.

Abstract:

Malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa is an undoubtedly rare and aggressive tumor, which charges patients above sixty years and does not have an association with sex. The nasal obstruction and epistaxis are the most related symptoms, although the presentation is late and unspecific, what delays the diagnosis and worsens the prognosis. The traditional approach has been the surgical treatment; the radiotherapy has also been used; however its effectiveness remains uncertain. The purpose of the present study is to report two cases of malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa and perform a literature review.

![]()

Introduction

Malignant melanoma of the nasosinusal mucosa is a rare tumor that represents 0.5 to 2% of the malignant melanomas altogether and it amounts to approximately 4% of all sinonasal region tumors1-4.

Since the first description by Lucke A. in 1869, according to Lund et al.4, malignant sinonasal melanoma has been recognized as an extremely aggressive tumor and is associated with short-term poor prognosis. Malignant sinonasal melanoma originates from melanocytes present in the nasal fossa mucosa and paranasal sinuses. They present great variations in volume and shape and three main histology types are recognized: epithelium cell melanoma, spindle cell melanoma and mixed melanoma1. Its microscopic aspect varies a lot from case to case, and also from area to area of the same tumor, with great diversity of cell shape, very evident nucleoli, hyperchromatic nuclei and high number of mitosis, with evident melanotic granules5.

The purpose of the present study was to review the literature about the topic and to relate two cases of the entity, one male and one female subject, aged 75 and 88 years, respectively. Both cases were diagnosed in the 1st semester of 2002 in the areas of Otorhinolaryngology and Clinical Pathology, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Literature Review

Differently from cutaneous malignant melanomas, mucous malignant melanomas do not originate from precursor lesions. They occur normally in more advanced age patients, after the 6th decade of life. The mean age of onset is 64 years1, 4 ranging from 23 to 93 years1, 6, 7. We can state that both genders are affected similarly, resulting in no apparent correlation with gender1, 4, 7, 8.

The most common symptoms observed in patients who have malignant sinonasal melanomas are nasal obstruction and epistaxis, either isolated or associated. In cases published so far, at least one of these symptoms was present. Other associated symptoms are rhinorrhea, rhinolalia, hyposmia, frontal-orbital headaches, facial pain, exophthalmia, and diplopia, in cases in which there was affection of the orbit. Few patients reported initial painful symptomatology. Some authors suggested that patients who presented epistaxis had better prognosis than those with isolated nasal obstruction1, 9.

In the nasal assessment, which involves anterior rhinoscopy and fibronasolaryngoscopy, polypoid masses are visible with blue-darkish pigmentation or in tones of light yellow or transparent color, in cases of amelanocytic melanomas1, 3, 4. The most frequent tumor locations at diagnosis are nasal septum and inferior and middle turbinates. The most frequent sinonasal location is the maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses; frontal and sphenoid sinuses are rarely affected1. The precise site of tumor origin is sometimes very difficult to determine owing to the extension of the lesion at diagnosis. It hinders the identification of satellite lesions, in addition, there are concomitant areas of amelanocytic melanoma in many cases4.

The rate of ganglionar neck metastases varies in the different studies published, ranging from 10 to 50% of the patients1, 2, 7, 9. Other sites frequently affected by metastases are the lungs, liver, brain, skin and orbit, among others. According to the literature, distant metastases affect 40 to 76% of the patients1, 6, 8. Owing to the possibility of having cutaneous metastases, it is recommended to carry out careful dermatological examination of patients affected by mucous melanomas1.

In most cases, the initial tumor presentation is unilateral. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging help stage the lesion, defining its local and regional extension and ruling out the existence of lesions involving the meninges, cerebral tissue and large vascular structures.

The definite diagnosis is made by histopathology and immunohistochemical studies of the lesion, using its biopsy specimen. In general, tumor cells are positive for protein S100, VIM and HMB45. Epithelial markers (CEA, EMA, cytokeratins) are negative1,4,5.

The first choice treatment for malignant sinonasal melanoma is, according to most authors, radical surgery with wide surgical margins that include resection of the bone adjacent to the lesion1, 5, 6, 10. In cases of ocular affection, the surgical treatment includes exenteration of the orbit and in the presence of palpable adenopathies, some authors recommend neck dissection even though it is not a procedure conducted systematically1, 2.

Malignant sinonasal melanoma is traditionally said to be radio-resistant, even though some studies have suggested the possible benefits arising from radiotherapy. Hardwood et al. (1982)11 demonstrated in their publication better local control after postoperative radiotherapy and Gilligan and Slevin (1991)3 demonstrated complete remission of the lesion in 79% of the patients treated with radiotherapy. Lund et al. (1999)4, however, did not confirm the addition of radiotherapy to prolong the survival of patients. The retrospective nature of the studies, lack of standardization in procedures and the small number of treated patients do not allow the safe definition of the role of radiotherapy in the treatment of malignant sinonasal melanoma.

Radiotherapy is recommended in patients whose surgery is contraindicated, when it is not possible to completely resect the lesion, when the safety margins are compromised, or when there are recurrences not controlled surgically.

Chemotherapy is used fundamentally as palliative care and is indicated in patients with metastatic forms of the disease. The most used drugs are Actinomycin D, Cimetidine associated with Interferon and Cisplatin. The latter, according to what was demonstrated in some studies, is useful in local recurrence when combined to radiotherapy1, 5. In addition to Interferon, Interleukin 2 and BCG are other possibilities of immunotherapy treatment.

The prognosis of nasal fossa melanoma is bad since it is a very aggressive tumor, normally diagnosed in advanced stages of the disease. Some authors pointed out that more than 50% of the patients do not reach 3 months of survival after diagnosis4. Some patients die within some weeks or moths after the initial presentation of symptoms, with quick spread of the disease, regardless of surgical treatment. Others survive for a long period of time with no clinical manifestations of the disease until something compromises the immune balance, which leads to aggressive short term recurrence. Others survive for longer periods, combined with local and cervical metastases that can be surgically controlled.

Case Report

Case 1

Male patient, aged 75 years old, came to the Ambulatory of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clinicas, UFMG in February 2001, with history of an episode of significant epistaxis on the right approximately 8 months before and sporadic posterior episodes of smaller intensity. He complained of ipsilateral progressive nasal obstruction that started concomitantly to the onset of nasal pyramid bulging on the right. The patient did not complain of pain or general status affections.

Upon physical examination, he presented nasal pyramid bulging on the right, extending as far as the maxillary region and mild proptosis on the right. Anterior rhinoscopy showed polypoid lesion, on the right nasal fossa, yellowish and with some darkened areas, occupying the nasal fossa in all its extension and causing partial destruction of the nasal septum with deviation to the left. Posterior rhinoscopy was not performed because the patient did not cooperate; otoscopy was within the normal range. We did not detect the presence of increased lymph nodes on the neck region.

Computed tomography of paranasal sinuses revealed presence of bulky mass of partially defined contours in the sinonasal cavity, predominantly on the right. The formation extended posteriorly, obstructing almost completely the ethmoidal cells associated with destruction of the papyraceous lamina on the right and extra-choanal post-septal and ipsilateral orbital invasion. Another abnormality was bone rarefaction on the posterior portion of the maxilla and vertical projection of the palate to the right with consequent extension of mass to the pterygopalatine recess and mastication space. The right ocular bulb was at proptotic position (Figure 1).

The diagnostic hypotheses made were inverted papilloma and neoplasm.

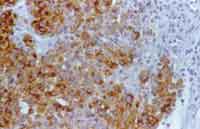

The pathology showed extensive areas of necrosis and large cell proliferation, with eosinophilic cytoplasm and hypertrophic, pleomorphic, hyperchromic nuclei with evident nucleoli. Chromatin was gross and granular, and the specimen presented hemorrhage and neutrophilia. Based on histology data, the hypothesis of melanoma was made. The immunohistochemical test showed positive result for S-100 protein, vimentin, HMB-45 and MART-1. EMA, AE1/AE3, desmin and LCA were negative (Figure 2). Based on immunohistochemical findings associated with histopathology analysis, we confirmed the diagnosis of melanoma.

Since it was a highly invasive lesion, we preferred radiotherapy treatment with 20 sessions of radiotherapy (180 Gy each) that provided initial improvement of nasal obstruction and epistaxis. After 4 months of post-radiotherapy evolution, he presented recurrence of nasal obstruction and epistaxis, increase of proptosis and bulging of the nasal pyramid. There was exteriorization of the lesion through the nasal vestibule on the right and increased size on the left nasal fossa, in addition to submandibular lymph node metastases on the same side.

To present, the patient is being administered chemotherapy of interferon, in order to reduce the tumor lesion and decrease nasal obstruction and epistaxis episodes.

Case 2

Female patient aged 88 years, Caucasian, came to the Ambulatory of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clinicas, UFMG in June 2001, with history of sporadic episode of epistaxis on the left nasal fossa with two months of evolution. She did not report nasal obstruction or orofacial pain. She reported bilateral hearing loss and vertigo.

Upon physical examination, we noticed a polypoid, bleeding and yellowish lesion that occupied the left nasal fossa on its middle and posterior thirds. The other areas of the ENT examination did not present abnormalities, and there were no neck region enlarged lymph nodes. The patient had anemia even though there was no general health compromise.

Computed tomography of paranasal sinuses revealed a soft tissue density mass obliterating the middle and inferior portions of the left nasal fossa and extending as far as the rhinopharynx. There was no bone destruction adjacent to the lesion (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Axial section CT scan showing extensive tumor mass in the right sinonasal cavity.

Figure 2. Malignant sinonasal melanoma. Section showing positive results of HMB-45. 400X.

Figure 3. Coronal section CT scan showing the lesion occupying the middle-inferior third of the left nasal cavity.

Figure 4. Axial section CT showing the lesion on the rhinopharynx on the left.

The diagnostic hypotheses were inverted papilloma and neoplasm.

The pathology revealed findings of undifferentiated neoplasm whose morphology suggested melanoma, with moderate quantity of cytoplasm cells, sometimes light in color, and central atypical nuclei with rare mitosis figures and frequent intra-nuclear cytoplasmatic pseudo-inclusions.

The immunohistochemical test revealed malignant neoplasia with airway pattern and morphologic characteristics of melanoma, with positive results for protein S-100, vimentin and HMB-45. Since it was a lesion that respected the anatomical limits of the nasal fossa with no invasion of adjacent bone structures, we decided for surgical treatment. The family refused any treatment owing to the advanced age of the patient.

Discussion

nasal fossa melanomas are rare tumors of poor prognosis that present late and non-specific symptomatology. They are normally unilateral in the initial phase and the main symptoms are nasal obstruction and epistaxis, as observed in the cases reported here. There is no correlation with gender and they normally affect patients in the 6th decade of life.

Most of the time, diagnosis is histopathological and made in advanced stages of the disease. The first line treatment is surgery, provided it is not contraindicated. There are discussions concerning efficacy of radiotherapy treatment, being that some authors defend their use only as a palliative measure that would mitigate the esthetical and functional damages4. In the first case described here, despite that, we decided for initial radiotherapy treatment owing to the extension of the local and regional lesion. There was temporary improvement and four months after, the patient experienced lesion recurrence, which confirmed the data from the literature. The association between chemotherapy and immunotherapy techniques is also inconclusive, requiring further studies to better understand the risk and prognostic factors.

CLOSING REMARKS

Nasal fossa melanoma, although rare, should be included in the differential diagnosis of unilateral neoplasia of nasal fossa, especially in the presence of nasal obstruction and epistaxis in elderly patients that present, in the physical examination, polypoid lesions of darkened or yellowish aspect in the nasal fossa.

The early diagnosis is extremely important, and it can determine better prognosis for the patient.

References

1. Enée V, Houliat T, Truilhé Y, Darrouzet V, Stoll D. Mélanomes malins des muqueuses naso-sinusiennes. Etude rétrospective à propos de 20 cas. Rev Laringol Otol Rhinol 2000;121(4):243-250.

2. Ghichard CH, Polonowski JM, Bost P, Russier M, Lefebvre B, Manipoud P, Irthum B, Gilain L. Mélano malins des Fosses Nasales et des Sinus. A propos de 4 cas. JFO 1997;46,1:27-31.

3. Gilligan D, Slevin NJ. Radical radiotherapy for 28 cases of melanoma in the nasal cavity and sinuses. Brit J Radiol 1991;64:1147-1150.

4. Lund VJ, Howard DJ, Harding L, Wei W. Management options and survival in malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa. Laryngoscope 1999;109:208-211.

5. García TM, Toledo MAA, Legaza ES, Báez JM, Galera GS, Domínguez MO. Melanoma epitelioide amelanótico de fosas y senos paranasales. Anales ORL Iber-Amer 1999;XXVI,4:393-400.

6. Lorre TR, Mullins AP, Spellman J, North JH, Hicks WL. Head and neck mucosal melanoma: A 32 year review. Ear, Nose & Throat J 1999;372-374.

7. Mane J, Stoll D, Delaunay MM, Traissac L. Mélanome des muqueuses ORL Rev Laringol Otol Rhinol 1992;113:179-183.

8. Vinel V, Dehesdin D, Marie JP. Mélanome des fosses nasales et des sinus. A propos d'une série de 7 cas. Rev Laringol Otol Rhinol 1990;111:61-64.

9. Crawford R, Tron V, Rivers R, Ma JK. Sinonasal malignant melanoma - A clinicopathologic analysis of 18 cases. Melanoma Research 1995;5:261-265.

10. Conley JJ. Melanomas of the mucous membranas of the head and neck. Laringoscope 1989;99(12):1248-1254.

11. Hardwood AR, Cumming BJ. Radiotherapy for mucosal melanomas. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys 1982;1121-1126.

1 Joint Professor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Ophthalmology and Speech Therapy and Audiology, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Pathology, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

3 Otorhinolaryngologist, Doctorate studies under course, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

4 Resident Physician in Otorhinolaryngology, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

5 Undergraduate, Medical School, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Affiliation: Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Ophthalmology and Speech Therapy and Audiology, Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Address correspondence to: Dr. Roberto Eustáquio Santos Guimarães - Avenida Pasteur, nº 88 4° andar Bairro Santa Efigênia, Belo Horizonte MG 30150-290 - Tel/Fax: (55 31) 3222-2891 - E-mail: rguimaraes@alcance.com.br

Article submitted on March 20, 2002. Article accepted on May 09, 2002.