Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 5 - (20º)

Relato de Caso

Pages: 705 to 709

MIDLINE CERVICAL CLEFT

Author(s):

José V. Tagliarini1,

Emanuel C. Castilho2,

Jair C. Montovani3

Keywords: branchial region, abnormalities, surgery.

Abstract:

The midline cervical cleft is an unusual congenital anomaly of the ventral neck and fewer than 100 cases have been reported overall and the first described by Bailey in 1924. This anomaly is report in association with median cleft of lower lip, cleft mandible and tongue, and hypoplasia of other midline neck structures. Its considered an anomaly originated from the two first branchial arches. The treatment of this cleft is a vertical complete excision and a closure with multiple Z-plasty. Many authors recommend avoid linear closure and prefer multiple Z-plasty for evicted fibrosis and local retraction. In this paper we report 2 case of this anomaly and the literature is reviewed.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Congenital midline cleft of the neck is a rare anomaly of the ventral portion of the neck and there are nearly 100 cases reported in the literature 1-13, whose first case was described by Bailey in 1924 1. This defect is found in association with midline lower lip cleft, mandible and tongue clefts, and hypoplasia of other midline cervical structures. It is believed that it is a malformation of branchial arches 2. Since it is a rare pathology, difficult to diagnosis, we report two cases seen in our service and the review of the literature.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Congenital midline cervical cleft is a rare anomaly of the ventral portion of the neck that can have variable extension in the vertical direction of the mentalis region to the suprasternal furcula 3. About 100 cases were reported in the literature and approximately 50 of them were published in English 4. The cleft is present since birth, but it may be left unnoticed and then become apparent as the child grows 4, 5. It may vary in extension and width and according to a study of 12 cases, length ranged from 4 to 12 cm and width ranged from 6 to 14 mm 6.

There is controversy in the literature whether the anomaly represents a real cleft; Fincher and Fincher (1989) described it as a fake cleft because it does not present separation of skin flaps from the margins and extends partially through the skin layers 7. Even though the anomaly is not identified in most cases, it is frequently visualized during crying at birth, followed by rigidity and retraction, which turns it into a scar if not surgically corrected 2. The lesion affects more female subjects 3. Eastlack et al. (2000), in a comprehensive review, found approximately 100 cases and only 14 were male subjects 4. Çelinkursun et al. (2001) reported one more case of a 12-year-old male child 8. The aspect at birth is of a midline defect on the neck skin that seems to be a fold recovered by atrophic skin approximately 5mm wide and it occurs at any level between the mentalis and the sternal furcula. It is frequently observed as a small projection in the upper border of the cleft and there may be a sinus associated with the caudal portion that can drain mucoid material. There is always some subcutaneous thickness associated with the defect, such as a subcutaneous cord or string that can lead to neck folds 3. In severe cases, this fibrous cord may cause anterior cervical contracture that can be accentuated as the child grows up 1, 3.

In addition to local findings, the cleft can be associated with other head and neck anomalies, including lower lip, mandible, mentalis and tongue clefts 4, 9, delay in mandible development 4, and hypoplasia or absence of neck supporting structures such as the hyoid bone 4, 9, 10. There are some reports of the association with bronchogenic cysts 1, 4, 7, 11 and thyroglossus duct anomalies 4. Associated defects in other parts of the body include sternal cleft, midline abdominal fold or anomaly of abdominal raphe, midline hemangioma 4, as well as congenital heart diseases such as intracardiac anomalies or ectopias 4.

Histological findings of the lesions are not specific 3. The epithelium that recovers the anomaly is parakeratotic stratified epithelium and the most consistent finding is absence of epithelial annexes in the dermis 3, 4. Skin appendices of the lesion have normal epithelium and may contain cartilage or musculoskeletal tissue 4. The sinus or the fistula associated with the lesion is normally recovered by cylindrical or columnar pseudostratified epithelium and it frequently demonstrates association with seromucinous glands 7, 10. The fibrous cord that is under the cleft has different microscopic structure and it may include musculoskeletal bundles that are histologically similar to congenital torticollis 4.

The diagnosis of this defect is clinical. The clinical pathology findings, even though specific, may be associated with the clinical observation to help confirm the diagnosis 4. The treatment of the lesion consists of vertical excision of the lesion and defect repair resulting from resection. Most authors recommend not performing simple repair, preferring closure with the use of multiple z-plasty 1-14. Z-plasty is conducted rather than primary closure to reduce the risk of occurrence of scar contracture secondary to surgery, which can reduce mobility of the neck and cause anterior open bite with microgenia 6. Breton and Freidel (1989) used wide resection of the anomaly and repair of the defect by using myocutaneous flaps from major pectoralis muscle associated with genioplasty by symphysis osteotomy by propulsion 12. The surgery can be conducted, if possible, in the first months of life to prevent the onset of mandible exostosis secondary to traction caused by the fibrous cord 4. Early correction of the deformity can also prevent contractures and cosmetic deformities that may require late corrections 4.

Different pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed to explain midline cervical cleft: amniotic adherence and vascular anomalies that cause localized tissue ischemia, necrosis and scars; persistence of thyroglossus duct or cyst remains; compression of the cervical area by the pericardial roof in initial stages of embryonic development/ absence of mesenchymal tissue in the cervical midline, and persistence of mandible arch groove combined with deficient mesenchymal differentiation 6.

Any discussion on etiology of this abnormal and midline branchiogenic syndromes lead to review of the development of branchial arch pairs, especially the first (mandible) and second (hyoid) arches. The studies conducted in bird embryos demonstrated that virtually all tissue from the ventral portion of the neck is derived from the neural crest. Branchial arches, prominent in 4th and 5th-week embryos, normally grow medially with the migration of cell mass from mesoderm, resulting in midline fusion, whereas ectoderm is pulled outwards, flattening the ventral groove on the midline. Mesodermal growth failure or merger of branchial arches respond for the spectrum of branchial anomalies reported. Anomalies in cell migration time, deficient amount of cell derived from the neural crest, or anomalies of the interaction of these cells with the local environment may be responsible for failure in fusion. This observation suggests that if migration mesoderm along the second arch is deficient or delayed, it may lead to isolated cervical cleft. If there is major bilateral deficiency of the first arch, however, there is a list of complicated manifestations such as inferior gnathoschisis with mandible and tongue cleft, cervical cleft and absence of hyoid bone and other supporting structures of the neck. Branchial arches migrate towards the cephalocaudal region, with the mandible arch closed on the midline before the hyoid arch. Inferior arches occupy a more lateral position and migrate later. Thus, whatever the reason, mandibular arch does not complete its closure in the midline and then successive closure may occur in more caudal arches. Whether this pathogenic mechanism is absolutely true or not, it seems clear that all clefts of branchiogenic origin are related to the time period and intensity of mesodermic fusion 6.

CASE REPORT

Case 1:

Female 4-month-12-day old subject. The father reported in the initial visit that she had presented a small lump on the neck since her birth, not reporting discharge or anterior episodes of local infection. The clinical history comprised a child born of cesarean section, weighting 4,250 kg, no drugs were used during pregnancy and there were no prenatal infections. Upon physical examination, she presented midline lesion forming a cord, comprising atrophic skin that extended to the furcula of the region up to the submentalis area, where it formed a 5mm nodule and presented a small 2mm orifice in the submentalis region (Figures 1A and 1B). We ordered TSH and T4 dosages and they were normal. We conducted thyroid gland scintigraphy, which presented normal result. She remained undiagnosed for 5 years and after this period she was submitted to surgery by spindle incision of the skin orifice and subcutaneous dissection of the fistula on the submandibular region up to the level of the furcula (Figure 1C and 1D). Section of the end of the fistula at the level of the furcula through horizontal incision at this same level. To close the remaining wound we used multiple z-plasty technique to prevent recurrence of cutaneous cord. The lesion was referred to clinical pathology analysis that confirmed the diagnosis of fibrous cord adhered to the skin appendix (Figure 1E). The child was followed-up for 1 year with no signs of recurrence.

Case 2:

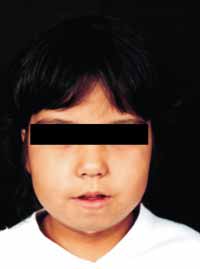

Male 4-month-old patient. According to the mother, since birth he had presented an opening on the neck with drainage of clear and transparent secretion. After being discharged from hospital using a cream that contained antibiotics, the drainage stopped and thin skin grew over the orifice, closing it. The child was born at term, weighting 3,150g. The mother reported that she had had gestational diabetes mellitus. Upon clinical examination, we detected midline cervical lesion recovered by shinny atrophic skin with subcutaneous cord that extended from the mentalis region to the sternal furcula (Figures 2A and 2B). The child presented mild mandibular retrognathia and open bite. At the age of 18 months, he was submitted to surgery with spindle excision of lesion and subcutaneous dissection of fistula of submandibular region up to the level of furcula, with section of the end of the fistula at this level. Upon closing the remaining defect, the technique used was multiple z-plasty (Figure 2C) to prevent fibrous retraction or recurrence of skin cord. Clinical pathology analysis of the lesion showed it was a fibrous cord adhered to the skin appendix, surrounded by lymphoplasmocytarian dense infiltrate (Figure 2D). The child remained in ambulatory follow-up for 3 months with good esthetical and functional results and after this period, the family gave up follow-up.

DISCUSSION

We reported midline cervical cleft cases to describe in the Brazilian literature this rare affection of the branchial system. Thus, the main goal is to prevent situations such as the one in the first case, in which the child was followed up for 5 years because there was no diagnosis. Early recognition of this malformation allows immediate treatment with better esthetical results, preventing the form of retrognathia that can result in the traction caused by cutaneous cord 6. We should also bear in mind the possibility of having other associated anomalies that should be identified before surgical treatment 1, 4, 7, 11. We agree with most authors that used multiple z-plasty in treating the cases rather than primary closure, given that the likelihood of recurrence of subcutaneous cord is smaller 1-11,13-14. The use of myocutaneous flap or major pectoralis muscle and genioplasty would be a treatment option for sequels or for cases of late diagnosis 12.

CONCLUSION

Midline cervical cleft is a rare embryonic defect, the embryonic mechanism responsible for its onset remains still quite controversial and we should bear in mind that it may be associated with other midline malformations. Early diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment prevents both sequels by delay in surgical treatment and neck contracture owing to incomplete excision. According to most authors, the repair should be performed with multiple z-plasty.

REFERENCES

01. French WE, Bale GF: Midline Cervical Cleft of the Neck with Associated Branchial Cyst. Am J Surg 1973; 125 (3): 376-81.

02. Minami RT, Pletcher J, Dakin RL. Midline cervical cleft: a case report. J Maxillofac Surg 1980; 8:65-8.

03. Maddalozzo J, Frankeel A, Holinger LD. Midline Cervical Cleft. Pediatrics 1992; 92:286-7.

04. Eastlack JP, Howard RM, Frieden IJ. Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft: Case Report and Review of the English Language Literature. Pediatr Dermatol; 2000; 17(2):118-22.

05. Nicklaus PJ, Forte V, Friedberg J. Congenital mid-line cervical cleft. J Otolaryngol 1991; 21(4): 241-3.

06. Gargan TJ, McKinnon MK, Mulliken JB. Midline Cervical Cleft. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985; 76(8): 225-9.

07. Fincher SG, Fincher GG. Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft with subcutaneous fibrous cord. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;101(3):399-401.

08. Çelinkursun S, Demirbag S, Öztük H, Sürer I, Sakarya MT. Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft. Clinical Pediatrics 2001; 40(6):363-4.

09. Maschka DA, Clemons JE, Janis JF. Congenital Midline Cervical Cleft Case report and review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995; 104:808-11.

10. Van der Staak FHJ, Pruszczynski M, Severijnen RSVM, Van der Kaa CA, Festen C. The midline cervical cleft. J Pediatr Surg 1991; 26(12): 1391-3.

11. Ayache D, Ducroz V, Roger G, Garabédian EN. Midline Cervical Cleft. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1997; 40(2-3):189-93.

12. Breton P, Freidel M. Bride Cervical Médiane Congénitale. Ann Chir Plast Esthét 1989; 34(1): 73-6.

13. Goldman NC. Congenital midline cervical cleft- A rare clinical entity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994; 111(1):148-9.

14. Andryk JE, Kerschner JE, Hung R, Aiken JJ, Conley SF. Mid-line cervical cleft with a bronchogenic cyst. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999; 47(3):261-4.

Figura 1A

Figura 1B

Figura 1C

Figura 1D

Figura 1E

Figura 2A

Figura 2B

Figura 2C

Figura 2D

*Assistant Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Medical School, Botucatu - UNESP.

** Otorhinolaryngologist, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Medical School, Botucatu - UNESP.

***Joint Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Medical School, Botucatu - UNESP.

Address correspondence to: José Vicente Tagliarini - Departamento de Oftalmologia, Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço - Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - Distrito de Rubiăo Júnior s/n - Botucatu - SP - CEP 18618-000 - Tel/Fax (55 14) 3811-6256 - E-mail: vicente@fmb.unesp.br

Study presented at 36o Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, in Florianópolis (SC), in 2002.