Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 5 - (4º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 602 to 607

Comparative study of histological and immunohistochemical aspects of spontaneous cholesteatomas of the external ear canal and acquired cholesteatoma of the middle ear

Author(s):

Fernando de Andrade Quintanilha Ribeiro1,

Celina Siqueira Barbosa Pereira2,

Renata de Almeida3

Keywords: cholesteatoma, external ear canal, middle ear, CK16, KI-67.

Abstract:

Introduction: A comparative analysis between the histological and the immuno histochemical (Ki-67 and CK-16) characteristics of spontaneous cholesteatomas of the external ear canal and acquired cholesteatomas of the middle ear was carried out. Material and Methods: Fragments of external ear canal cholesteatomas were submitted to histological and immunohistochemical studies to evaluate the expression of CK-16 and of the nuclear antigen Ki-67 in the matrix cells. Results were compared to the same studies in acquired cholesteatomas of the middle ear. Results: Histological and immunohistochemical aspects studied were identical in both types of cholesteatomas studied. Discussion: This study suggests that cholesteatomas of the external ear canal are caused by na abnormal behavior of the cells of the epithelium of the external canal with hyperproliferative properties. This potential could be explained by the presence of CK-16 at a location where these markers are not usually found. The hyperproliferative characteristic of the external ear canal cholesteatoma is possible due to the presence of the K-67 nuclear antigen in the epidermal suprabasal cells. It is possible that the disease is caused by an interaction between CK-16 and the cytocines (TGF-alpha),which are present in the subepithelial connective tissue undergoing na inflammatory process. Conclusions: The histological (presence of epithelial cones) and immunohistochemical (expression of CK 16 and the nuclear antigen KI-67) characteristics of both the external ear canal and the acquired middle ear cholesteatomas are identical.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The epidermis of the EAC (external auditory canal) similarly to the retroauricular one is commonly used as immunohistochemical control in acquired middle ear cholesteatoma. It is widely known that Ki-67 nuclear antigen is present only in few basal layer cells; however, the expression of this antigen is marked in cholesteatoma affecting also suprabasal layers. Cytokeratin 16 (CK16) is present only in juxta-tympanic portions, but it is frequently found in all middle ear cholesteatoma cases.

Cytokeratin 16 and ki-67

Cytokeratins are proteins present in the cytoplasm of intermediary filaments that form cytoskeleton of epithelial cells. Twenty different cytokeratins, characteristic of a certain type of epithelia 1, have been described. Cytokeratin 16 is present in the cells of hyperproliferative epithelium, such as verruca vulgaris, actinic keratosis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, carcinoma verrucosus, squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas2. Cytokeratin is absent in normal skin, except for the areas under pressure or friction, such as plantar and digital pulp of the thumb, and in epithelial cells of hair folicule3.

Ki-67 is an antigen present in cell nuclei during multiplication phase (late G1 , S, G2 phases and M cell cycle). This antigen could be demonstrated through immune histochemical reactions, using the antibody also known as Ki-67, or MIB1, MIB2 and MIB3 antibodies, which are considered equivalent to Ki-67 antibody. These antibodies normally react as antigens present in nuclei of the basal layer cells of the epithelium, which is a layer that has proliferative capacity and originates keratocytes that migrate to other layers of the epidermis4,5.

Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of the epidermis of external auditory canal.

External auditory canal is lined by squamous stratified keratinized epithelia with hairs, modified sebaceous and sweat glands (ceruminous) on its external third. The epithelium and a small amount of subepithelial connective tissue rest over cartilage and bone structure.

Some authors demonstrated cytokeratin 16 expression in an specific area of the external ear: in the inferior portion and juxta-tympanic portion of the external auditory canal, and epithelial cell in the stressed portion of the tympanic membrane near the fibrocartilaginous ring3. In the other regions of the external auditory canal the expression is similar to that found in healthy skin, or in other words, in epithelial cells of hair follicles present in the external portion of the canal.

With regard to Ki-67 nuclear antigen, it was found in less than 1% of the basal layer cells of the EAC and tympanic membrane epithelium6.

Histological immunohistochemical characteristics of middle ear cholesteatoma

Acquired middle ear cholesteatoma is a disease characterized by the presence of keratinized stratified squamous epithelium inside its cavity, normally recovered with simple pavement epithelium with areas of pseudostratified ciliated columnar and simple cubical epithelium. This disease is normally related to epithelial desquamation and secondary infection followed by bony erosion, and may evolve to intra and extracranial complications. With regard to histology, cholesteatoma frequently presents areas with acanthosis and growth cones in which cells invaginate between basal cell layer and the inflamed perimatrix.

Presence of cytokeratin 16 was demonstrated in cholesteatoma matrix in suprabasal layers of the epithelium, which is typical hyperproliferative epithelium. The expression of antinuclear antigen K-67 was approximately two to three times higher in basal cells of the cholesteatoma basal matrix than in the external auditory canal7. The antigen was also found in suprabasal cells including the most apical ones, indicating hyperproliferative stage of epithelial cells8.

The higher the acanthosis and growth cone formation, the greater the expression of cytokeratin 16 and nuclear antigen Ki-67 will be in the matrix of acquired middle ear cholesteatoma.8 This relation is even higher in increased levels of perimatrix inflammation, suggesting that production of local inflammatory mediators (cytokines) increases the production of keratinocytes9. Several authors have already reported large amounts of TGF- in cholesteatoma cells. The TGF- is a cytokine that increases gene transcription of cytokeratin 16, activating keratinocytes proliferation 10. Not only TGF- , but also several other cytokines have been abundantly found in middle ear cholesteatoma compared against the epidermis of the external auditory canal. Cytokines are proteins produced by cells that trigger effects in other closer or distant cells, generating a cascade effect responsible for the inflammatory process. It may cause vasodilation, osteolysis, cell migration and granulation tissue formation. Recent studies reported the interaction between the cytokines, located in perimatrix, and their receptors, probably present in the matrix cells of cholesteatoma, which has a role to play in the aggressiveness of the disease11,12.

Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of external auditory canal cholesteatoma

The cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal is a relatively rare disease characterized by its aggressive and infiltrating behavior in the skin of the external auditory canal. Its etiology is controversial and has been described as caused by traumatic or congenital stenosis with desquamation of restrained, pressured or infected skin that can extend to the canal, causing the collapse of the tympanic membrane and invading the tympanic and mastoid portions. It may be more circumscribed or reported as necrotizing osteitis (benign necrotizing external otitis) 13,14; in such case, its etiology is related to singular tympanic bone vascular anatomy and if not properly treated, it can lead to circumscribed necrosis of the canal skin and bone. It could also be misinterpreted as other diseases such as obliterating keratosis (Keratosis obturans)15. In our opinion, cholesteatoma of external auditory canal is a spontaneous aggressive behavior of the canal skin. This behavior may lead to bone erosion and could be localized (normally in the inferior portion of the canal) or diffuse. The aggression may be confined to the canal or invade the tympanic cavity and mastoid. Several studies have reported such characteristics 16-18, but few trials evaluated immunohistochemistry of this skin19. These recent studies reported the present of TGF-? cytokine and EGF receptor in suprabasal layers of cholesteatoma matrix, as well as positive MIB1 cells in basal and suprabasal layers, typical of hyperproliferative tissues.

OBJECTIVE

To conduct histological and immunohistochemical study in spontaneous cholesteatoma fragments of the external auditory canal and compare the results with those obtained for acquired middle ear cholesteatomas.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Samples were collected from patients (25 years of age) presenting events of otorrhea since childhood, with worsening over the past years. The patient reported that in those former events, otorrhea was treated with lavage and dressings. Symptoms had worsened for one year, with constant and fetid otorrhea on the right ear, followed by hearing loss. Physical evaluation showed abundant desquamation of the right ear, upon its removal, it revealed enlarged canal, with perforation of the flaccid portion of the tympanic membrane. Left ear had desquamation retention of the inferior portion of the canal with normal tympanic membrane. Computed Tomography scan (CT scan) of the right ear presented irregular enlargement of the external auditory canal (Figure 1), and also erosion of ossicular chain. The same irregular canal enlargement was present on the left ear with normal tympanic cavity (Figure 2). The patient had undergone right side radical mastoidectomy, since it presented not only erosion of the canal but also skin migration to middle ear and mastoid. Left ear was operated on afterwards and localized erosion of the tympanic bone was found. Local debridement with homologous retroauricular skin flap was performed. The material collected was sent to analysis.

The collected material was fixed in 10% formaldehyde and processed through current techniques with paraffin inclusion and blocks were cut in 3mm thick sections by using a rotatory microtome, and then sent to histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Sections were stained in hematoxylin and eosin and sent to histological analysis. Non-stained slides and slides previously coated with organosilane adhesive were submitted to immunohistochemistry analysis by immunoperoxidase procedure performed in three steps and amplification system used was avidine-biontine-peroxidase, without previous tripsinization. Monoclonal antibodies were anti-Ki-67 clone Ki-S5 (Dako, Denmark) and keratin 16 (hyperproliferation-related keratin) Ab-1 clone LL025 (Neomarkers, USA).

RESULTS

Histological and immunohistochemical results were compared with previous sections made from fragments of acquired middle ear cholesteatoma8.

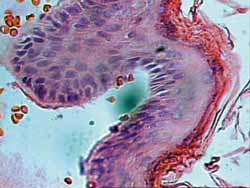

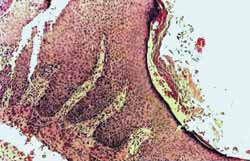

Histological evaluation evidenced keratinized stratified pavement type epithelium, with acanthosis sites and basal layer hyperplasia, forming epithelial cones (Figure 3) similar to those found in acquired cholesteatoma of the middle ear (Figure 3a).

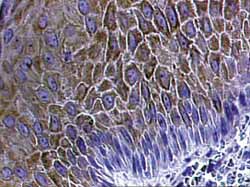

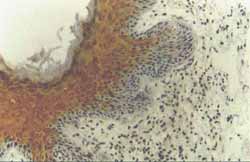

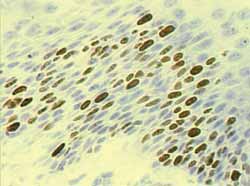

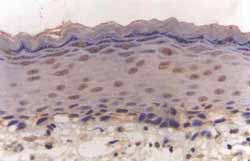

Immunohistochemical findings were that anti-cytokeratin 16 antibody strongly reacted with suprabasal matrix cells of the cholesteatoma of external auditory canal, similarly to those found in middle ear cholesteatoma (Figure 4, Figure 4a). Nuclear Ki-67 antigen was found in almost all basal cells of the matrix and also in several cells of suprabasal layers indicating enhanced keratinocytes proliferation, identical to those occurring in acquire cholesteatoma of middle ear (Figure 5, Figure 5a).

DISCUSSION

Conventionally, most of the authors agree that the etiology of the cholesteatoma external auditory canal could result from acquired stenosis (surgical or accidental), or even from congenital stenosis, and with retention of epithelial desquamation due to pressure or infection, it could result in canal erosion, membrane perforation or migration to middle ear. Localized stenosis could be reported as benign necrotizing external otitis and its etiology is related to deficient vascular features of the tympanic bone. In our opinion, the real cholesteatoma of external auditory canal, the one that occurs spontaneously, presents erosive characteristics due to the presence of intrinsic biomolecular factors, similar to those of the middle ear cholesteatoma.

Therefore, the epidermis of the external auditory canal does not express cytokeratin 16 under normal conditions, except in the inferior or juxta-tympanic portion, or in epithelial cells of hair follicles. As to Ki-67, it was found in less than 1% of the basal layer cells of the external ear portion of external ear.

Cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal, however, presents immunohistochemical characteristics that are quite different from those of the normal epidermis that covers this structure, but they are very similar to those characteristics of acquired middle ear cholesteatoma; in other words, it is formed by hyperproliferative epithelium. With regard to histology, the presence of acanthosis, basal layer cell hyperplasia and epithelial cone formation had some similarities with cholesteatoma of middle ear. Immunohistochemistry had marked expression of antibodies anti-CK16 and KI-67, typical hyperproliferative epithelia were also identical to those found in cholesteatoma of middle ear. In our opinion benign necrotizing external otitis would also be a more localized type of EAC cholesteatoma. Probably, this hyperproliferative potential would begin with the interaction of cytokeratin 16 and its cells with cytokines present in sub-epithelial inflammatory reactions, which would work as a triggering factor for such behavior.

New immunohistochemical studies must be conducted in order to properly differentiate and classify all the diseases of the EAC epidermis.

CONCLUSION

The epithelium of the external auditory canal cholesteatoma presents the same histological (epithelial cones) and immunohistochemical characteristics of acquired middle ear cholesteatoma, with presence of CK16 and of nuclear Ki-67 antigen in suprabasal layers, which are typical in hyperproliferative epithelia.

REFERENCES

1. Moll R, Franke WW, Schiller DL. The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell 1982; 31: 11-24.

2. Weiss RA, Eichner R, Sun TT. Monoclonal antibody analysis of keratin expression in epidermal diseases: a 48- and 56- kDalton keratin as molecular markers for hyperproliferative keratinocytes. J Cell Biol 1984; 98: 1397-405.

3. Broekaert D & Boedts D. The proliferative capacity of keratinizing annular epithelium. Acta Otolaryngol 1993; 113: 345-8.

4. Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker H, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol 1984; 133: 1710-5.

5. Brown DC & Gatter KC. Monoclonal antibody Ki-67: its use in histopathology. Histopathology 1990;17: 489-503.

6. Ergün S, Zheng X, Carlsöö B. Antigen Expression of epithelial markers collagen IV and Ki-67 in middle ear cholesteatoma. An immunohistochemical study. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1994;114: 295-302.

7. Sudhoff H, Bujía J, Fisseler-Eckhoff A, Holly A, Schulz-Flake C, Hildmann H. Expression of a cell-cycle-associated nuclear antigen (MIB1) in cholesteatoma and auditory meatal skin. Laryngoscope 1995; 105: 1227-31.

8. Pereira SB, Almeida CIR, Vianna MR. Imunoexpressão da Citoqueratina 16 e do Antígeno Nuclear Ki-67 No Colesteatoma Adquirido da Orelha Média. Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia 2002; 68:453-60.

9. Mayot D, Béné MC, Perrin C, Faure GC. Restricted expression of Ki-67 in cholesteatoma epithelium. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993; 119: 656-8.

10. Jiang CK, Magnaldo T, Ohtsuki M, Freedberg IM, Bernerd F, Blumenberg M. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor specifically induce the activation and hyperproliferation associated keratins 6 and 16. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1993; 90: 6786-90.

11. Yamamoto-Fukuda T, Aoki D, Hishikawa Y, Kobayashi T, Takahashi H, Koji T. Possible involvement of keratinocyte growth factor and its receptor in enhanced epithelial-cell proliferation and acquired recurrence of middle-ear cholesteatoma. Lab Invest. 2003 Jan; 83(1):123-36.

12. Alves ALRibeiro FAQ. O papel das citocinas no colesteatoma adquirido da orelha média:revisão da literatura. Revista Brasileira de O.R.L. Aceito para publicação em 04/01/2004.(cód. Ident.:04.01x10.)

13. Youngs R, Kwok P, Hawke M. Benign osteitis of the external auditory meatus. J Otolaryngol 1988 Oct; 17(6): 302-7.

14. Kumar BN, Walsh RM, Sinha A, Courteney-Harris RG, Carlin WV, Benign necrotizing osteitis of the external auditory meatus. J Laryngol Otol 1997 Mar; 111(3):269-70.

15. Persaud R, Chatrath P, Cheesman A. Atypical keratosis obturans. J Laryngol Otol 2003 Sep; 117(9): 725-7.

16. Vrabec JT, Chaljub G. External canal cholesteatoma. Am J Otol 2000 Sep; 21(5): 608-14.

17. Pachoal JR, Maunsell RC. Spontaneous cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2001; 122(4): 269-72.

18. Naim R, Riedel F, Hormann K. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Int J Mol Med 2003 May; 11(5): 555-8.

19. Adamczyk M, Sudhoff H, Jahnke K. Immunohistochemical investigations on external auditory canal cholesteatomas. Otol Neurotol 2003 Sep; 24(5): 705-8.

Figure 1. Right ear CT scan study with diffuse erosion of the external auditory canal.

Figure 2. Left ear CT scan in which it is also possible to see large diffuse erosion of external auditory canal.

Figure 3. Epithelium of fragment of cholesteatoma of external auditory canal, with evident hyperproliferative basal layer forming epithelial cones. Perimatrix is not present in this histological section (HE X 600).

Figure 3a. Section of fragment of middle ear cholesteatoma showing matrix with severe hyperplasia of basal cell layer, forming wide epithelial cones invading the perimatrix. Acanthosis and keratin lamellas are also evident. Presence of dense lymph-hystiocitarian infiltrate in the perimatrix (HE X 100).

Figure 4. Anti-CK16 antibody reaction markedly positive in suprabasal layers of the cholesteatoma of EAC epithelia (IH X 400).

Figure 4a. Anti-CK16 antibody reaction markedly positive in suprabasal layers of the matrix of middle ear cholesteatoma. Presence of acanthosis and hyperplasia of basal layer of the matrix forming wide cones invading the perimatrix (IH X200).

Figure 5. Antigen KI-67 reaction markedly positive in nuclei of basal layer cell of the EAC cholesteatoma epithelia extending itself to suprabasal layer (IH X 600).

Figure 5a. Antigen KI-67 reaction markedly positive in nuclei of basal layer cell of cholesteatoma of middle ear extending itself to the suprabasal layer (IH X 400).