Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 4 - (5º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 471 to 477

Local disseminating pattern of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue

Author(s):

Francisco S. Amorim Filho1,

Josias A. Sobrinho1,

Abrão Rapoport1,

Antonio S. Fava1,

Marcos B. Carvalho1,

Neil F. Novo2,

Yara Juliano2

Keywords: Key words: spreading, squamous cell carcinoma, base of the tongue.

Abstract:

Aim: To analyse the local spreading pattern through clinical delimitation of primary lesion extension as well as subsites involvement. Study Design: clinical nonrandomized. Material and Method: Files of 290 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the base of the tongue from Department of Head Neck and Surgery and Otorhinolaryngology of Hospital Heliópolis, Hosphel, São Paulo, Brazil from 1977 to 2000, were analysed. They were staged through TNM from UICC, and then through thoygh K square text with Z x N (Cochran) tables for assessment of sites and size association of neoplasia in relation of medium line invasion. Results: Male predominance (8:1) in 6th decade (41,0%), 83,8% were alcohol and tobacco dependent and 4,7% without this habbit. About symptoms, odinophagia (37,6%), lymphonode (21,7%) and medium time between tho first sympton and diagnosis of 6 months 62,0%). About staging, T1-T2 (18,3%), T3 (32,4%), T4(50,7%). Concerning local spreading: valecula (25,3%), epiglotis (18,7%), glottis (2,7%), anteriorly to lingual V (22,4%) and postero-lateraly to pharyngoepiglotic fold (6,6%), piriform sinus (2,2%). About medium line involvement (66,2%), 42,2% were (T2), 54,2% (T3) and 82,9% (T4). Conclusion: the SCC in T4 stage reach the medium line of base of the tongue in 82,9%.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Malign tumors affecting the head and neck correspond to 10% of all human neoplasm, 40% of which are on the oral cavity and oropharynx; the base of the tongue is the second most affected site1. In 90 to 95% of the cases, these tumors are represented by squamous cell carcinoma 1-7. Males between 50 and 60 years of age are most commonly affected.8 80% of the cases result from environmental, occupational and immune factors, as well as diet, virus and genetics9,10. Therefore, the dominant risk factor, common to most patients with oropharynx cancer, is alcohol associated with tobacco consumption 1,7,11-17.

Cancer of the base of the tongue is silent and normally of asymptomatic onset. Subsequently, there is significant growth of the neoplasia, followed by odynophagia and swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)3,7,18-20. Neoplasia of the base of the tongue is usually, ulcerated and infiltrated, poorly-to-mildly differentiated4,21-23. These tumors spread to weak tissues through neurovascular structures of the head and neck, as well as through the rich draining lymph system, and may affect other sites on the oropharynx and adjacent tissue; there is high dissemination rate to cervical lymph nodes.

Oropharynx is an area of difficult access and visualization. Many of our patients and health care providers are not aware of the disease affecting this site; therefore, there is great number of cases underdiagnosed during early stages. As a result of late diagnosis, there is high mortality rate of patients in the economically active age group and treatments are aggressive and mutilating, often making the reintegration of patient and his family impossible. The purpose of the present study was to analyze local disseminating patterns of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, through clinical delimitation of the extent of the primary lesion, and sub-sites involvement.

Knowledge of the disseminating pattern of these tumors, and their natural history will enable the development of the most appropriate treatment plan to each patient.

METHOD

We analyzed medical files of 290 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the base of the tongue from the Department of Head and Neck Surgery and Otorhinolaryngology of Hospital Heliópolis, Hosphel, Sao Paulo, Brazil, from 1977 to 2000. The inclusion criteria were: presence of lesions primarily located at the base of the tongue and histopathology consistent with squamous cell carcinoma. All patients had detailed loco-regional evaluation, including anterior and posterior rhinoscopy, oroscopy, indirect laryngoscopy, bidigital palpation of the base of the tongue, and neck palpation. During the loco-regional physical examination, we tried to identify features of the primary lesion, topography, extent, dissemination to adjacent tissues and its borders (focusing on midline involvement). The patients were classified according to the TNM system (UICC 1998)24, globally accepted to stage squamous cell carcinoma.

Results were evaluated by chi-square distribution test for tables Z x N (Cochran), whose purpose was the study of associations between tumor size and affected sites compared to midline involvement.

RESULTS

Of the 290 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, there was higher incidence among males (89.3%), male-to-female rate was 8:1. The affected patients were predominantly aged 60 years (41%). Most of our patients (83.8%) smoked and drank alcohol, and there were few cases (13 patients) of non-smokers and non-alcohol consumers.

The most common early symptoms reported by our patients were pain during swallowing (37.6%) and lump on the neck (21.7%), and the average time between the first symptom and diagnosis was up to 6 months (62.0%).

As for the tumor's macroscopic features, most cases showed ulcerative-infiltrative lesions (76.5%), followed by the vegetative type (10.3%).

The histological grade common to most patients was moderately differentiated (52.4%) (Table 1). All patients were staged by TNM system (UICC, 1998), where 94 patients were on stage T3 (32.4%) and 147 patients on stage T4 (50.7%) (Table 2).

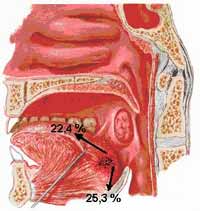

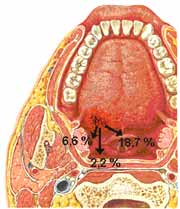

In our study, there were only three distant metastatic lesions, all affecting the lung. The squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue disseminated towards many sites of the oropharynx, as well as to other tissues. The posterior aspect of the oropharynx was the most affected one, when compared to other sub-sites. The primary tumor grew mainly towards the vallecula in 25.3% of the cases (Figure 1). On the opposite direction, the squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue grew towards the oral cavity, surpassing the lingual "V" and affecting the body of the tongue in 22.4% of the cases (Table 3).

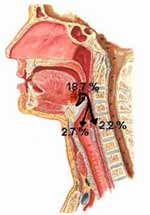

As the primary lesion grew towards the vallecula, the tumor of the base of the tongue also affected the lingual side of the epiglottis (18.7%). However, this invasion towards its laryngeal side and glottic area occurred in few cases (2.7%) (Figure 2).

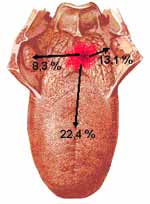

As for dissemination to lateral borders of the oropharynx, squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue affected the glossotonsillar fold in 122 cases, and the tonsil was subsequently affected in 24.4% of the cases (Figure 3).

Towards the postero-lateral part of the oropharynx, the primary tumor reached the pharyngoepiglottic fold in 61 cases and, subsequently, the pyriform sinus in 26 cases (Figure 4).

After studying whether the primary lesion surpassed or not the midline, we noticed that most cases of tumor of the base of the tongue (66.2%) invaded and surpassed the midline. Concerning the primary tumor size (T) and midline invasion, we noticed that advanced-stage lesions (T4) usually invaded the midline (Table 4). Comparing the different sites affected by the tumor of the base of the tongue and midline involvement, we noted that frequently, on different areas, the midline was invaded by the primary tumor (Table 5). As for the side affected by the tumor, there were no significant differences - the right side was slightly more affected (46.2%) than the left side.

DISCUSSION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue is considered a silent-growing lesion, whose onset is asymptomatic, affecting other areas of the oropharynx and even different tissues23; it is highly infiltrative and has dissemination potential to the neck, uni or bilaterally.

Late signs of tumors of the base of the tongue result from poor distribution of pain-sensitive fibers. When the patient shows symptoms, he already has disseminated cancer25. Upon initial presentation, the patient normally has advanced-stage disease and poor prognosis26.

We should know which are the most affected areas and local lymphatic channels to choose the most appropriate oncological treatment to these patients.

Men are more affected by this neoplasm than women, and one of the most important factors contributing to an unequal rate among men and women is excessive use of alcohol and tobacco by men. The most affected age group is about 60 years old8,23. In our study, the macroscopic findings of most patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue are ulcerative-infiltrative lesions. Muscles affected by the tumor, associated with swallowing of solid food and presence of local irritants (alcohol and tobacco) on the mucosa, create frequent irritation on this area, predisposing it to ulceration and pain during swallowing27.

The most common histological grade in our patients was moderately differentiated tumor. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas are most aggressive because they are more infiltrative, when compared to moderately and well-differentiated carcinomas3,28. Most of our patients are affected with advanced-stage tumors, T3 (32.4%) and T4 (50.7%)8,23,29. One of the contributing factors for the high rate of advanced cases is the location of the tumor on the base of the tongue, hindering direct visualization and access during physical examination of the area; often, health care providers are not able to see the primary lesion30,31. Assessment of the size of the primary tumor is important for diagnosis and choice of treatment. Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue may progress within the submucosa, in different directions and depths; as a result, it will become infiltrative and involve tongue muscles, towards weak tissues.

In our study, local disseminating patterns of the primary lesion were well documented; we noted that in most cases, the tumor grew towards the vallecula (25.3%), subsequently invading the lingual border of the epiglottis (18.7%).

Only few tumors spreading to the posterior aspect of the oropharynx and affecting the laryngeal aspect of the epiglottis invaded the glottic site (2.7%).

It is relatively common that lesions growing towards the vallecula and epiglottis may affect the pre-epiglottic space. The assessment of invasion at this site, deep in the vallecula, is only possible by CT scan.

When squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue grows towards the vallecula, there is higher chance that it will also affect the lingual aspect of epiglottis, rather than neighboring tissues or become restricted to the primary site.

The extent of the primary lesion on the oral cavity was noticed in 22.4% of the cases. In these cases, the tumor surpassed the lingual "V", subsequently invading the body of the tongue and infiltrating into deep muscles. As a consequence, tongue movement was decreased and the voice changed to "hot potato voice" type 2.

As for lateral growth, there was invasion of glossotonsillar fold in 13.1% of the cases, and in over half of these cases there was also involvement of the tonsil (8.3%). The lack of natural barriers between both structures enables dissemination to this site of the oropharynx. We may also note that when these tumors invade the anterior aspect of the tongue's muscles, they may grow laterally, invading the tonsils.

Through bidigital palpation, when there is invasion of glossotonsillar groove, it is possible to determine early infiltration into the tonsil. Postero-laterally, squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue affected the pharyngoepiglottic fold (6.6%) and, consequently, there was invasion of pyriform sinus in 2.2% of the cases. Less frequently, tumors of the base of the tongue affect the hypopharynx; in such cases, the lesion is on advanced stage and the prognosis is poor, but in most cases, its growth is limited to the borders of the oropharynx.

Tumor growth towards the opposite direction of the primary lesion, surpassing the midline of the base of the tongue, occurred in most patients with advanced-stage lesions. However, when we evaluated all our patients according to stage (T) of the primary lesion and midline involvement, we noted that with Chi-square test there was significant association between the size of the primary tumor and midline invasion. Most advanced-stage tumors (T4) affected the contralateral side in 83% of the cases.

As carcinoma grows, slowly and progressively, it frequently invades and surpasses the midline; that way, it affects even more the rich crossed draining lymph channels of the tongue, spreading tumor clots to contralateral lymph channels and affecting tissues opposite to the primary lesions.

When we evaluated the different areas affected by the tumor of the base of the tongue and midline involvement, we noted that with Chi-square test there was no significant association between the affected site and midline invasion. It is worth noting the great percentage of midline invasion among all sides invaded by the tumor.

We believe that midline involvement and subsequent dissemination to the opposite side of the primary lesion is a natural tendency of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, which affects the contralateral muscles and the rich crossed draining lymph channels of the base of the tongue.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue is an aggressive tumor, which benefits from difficult access and poor sensitive fibers on the area to grow unnoticed, early invading the deep muscles of the base of the tongue and its rich draining lymph channels, spreading neoplastic cells to neck lymph channels25.

As a result of lack of natural barriers on the oropharynx, the primary tumor easily grows to other sub-sites and tissues.

Detailed physical examination and bidigital palpation of the base of the tongue must be the routine procedure among patients over 40 years of age, with history of increased alcohol and tobacco use. In general, palpation is insufficient to detect the extent of the tumor of the base of the tongue; therefore, in some cases, palpation of patients under anesthesia is mandatory before any surgical procedure is started.

REFERENCES

1. Kanda JL. Epidemiologia, diagnóstico, patologia e estadiamento dos tumores da faringe. In: Carvalho MB, ed. Tratado de cirurgia de cabeça e pescoço e otorrinolaringologia. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2001.

2. Adamns GL. Cancer of the oropharynx. In: McQuarrie DG, Adamns GL, Shons AR, Browne GA, eds. Head and neck cancer-clinical decisions and management principles. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1986.

3. Kowalski LP, Franco EL, Torloni H, Fava AS, Andrade Sobrinho J, Ramos G, Oliveira BV, Curado MP. Lateness of diagnosis of oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: factors related to tumor, the patients and health professionals. Oral Oncol Eur J Câncer 1994; 30:167-73.

4. Civantos FJ, Goodwin Junior WJ. Cancer of the oropharynx. In: Myers EN, Suen JY, eds. Cancer of the head and neck. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1996.

5. Plasencia JD, Ramella ET, Ravello JA, Gavidia CG, Abanto WC, Acosta RV. Carcinoma epidermóide de cavidad oral y orofaringe. Diagnostico 1996; 35:14-21.

6. Schantz SP, Harrison LB, Forastiere AA. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. In: De Vitta JR VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997.

7. Seikaly H, Rassekh CH. Oropharyngeal cancer. In: Bailey BJ, Calhoum KH, Deskin RW, Johnson JT, Kohut RF, Pillsbury III HC, Tardy Junior ME. Head and neck surgery: otolaryngology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

8. Weber PC, Myers EN, Johnson JT. Squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1993; 250:63-8.

9. Day GL, Blot WJ, Austin DF, Bernstein L, Greenberg RS, Preston-Martin S, Schoenberg JB, Winn DM, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni Junior JF. Racial differences in risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer: alcohol, tobacco and other determinants. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85:465-73.

10. Boffetta P, Merletti F, Magnani C, Terracini B. A population-based study of prognostic factors in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol Eur J Cancer 1994; 30:369-73.

11. Keller AZ, Terris M. The association of alcohol and tobacco with cancer of the mouth and pharynx. Am J Public Health 1965; 55:1578-85.

12. Rothman K, Keller A. The effect of joint exposure to alcohol and tobacco on risk of cancer of the mouth and pharynx. J Chron Dis 1972; 25:711-6.

13. Rothman KJ, Garfinkel L, Keller AZ, Muir CS, Schottenfeld D. The proportion of cancer attributable to alcohol consumption. Prev Med 1980; 9:174-9.

14. Carvalho MB, Kanda JL, Andrade Sobrinho J, Kowalski LP, Rapoport A, Fava AS, Góis Filho JF, Chagas JFS. Estudo clínico dos tumores malignos da orofaringe. Rev Bras Cir Cab Pesc 1985; 9:13-27.

15. Brugere J, Guenel P, Leclerc A, Rodriguez J. Differential effects of tobacco and alcohol in cancer of the larynx, pharynx and mouth. Cancer 1986; 57:391-5.

16. Blitzer PH. Epidemiology of head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol1988; 15: 2-9.

17. Franco EL, Kowalski LP, Oliveira BV, Curado MP, Pereira RN, Silva ME, Fava AS, Torloni H. Risk factors for oral cancer in Brazil: a case control study. Int J Cancer 1989; 43:992-1000.

18. Tuyns AJ. A etiology of Head and Neck Cancer: Tobacco, Alcohol and Diet. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 1991; 46:98-106.

19. Carter RL, Pittam MR, Tanner NSB. Pain and dysphagia in patients with squamous carcinomas of the head and neck: the role of perineural spread. J Royal Soc Med 1982; 75:598-606.

20. Dicker A, Harrison LB, Picken CA, Sessions RB, O'Malley BB. Oropharyngeal cancer. In: Harrison LB, Sessions RB, Ki Hong, W, eds. Head and neck cancer: a multidisciplinary approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999.

21. Barrs DM, DeSanto LW, O'Fallon WM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil and tongue base region. Arch Otolaryngol 1979; 105: 479-85.

22. Rollo J, Rozenbom CV, Thawley S, Korba A, Ogura J, Perez CA, Powers WE, Bauer WC. Squamous carcinoma of the base of the tongue: a clinicopathologic study of 81 cases. Cancer 1981; 47:333-42.

23. Johansen LV, Grau C, Overgaard J. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the oropharynx, an analysis of treatment results in 289 consecutive patients. Acta Oncol 2000; 39:985-93.

24. TNM - Classification of Malignant Tumours (UICC). Wiley-Liss, Inc. 1997.

25. Nason RW, Anderson BJ, Gujrathi DS, Abdoh AA, Cooke RC. A retrospective comparison of treatment outcome in the posterior and anterior tongue. Am Jour Surg 1996; 172:665-9.

26. Perlmutter MA, Johnsons JT, Snyderman CH, Cano ER, Myers EN. Functional outcomes after treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 128:887-91.

27. Ruff T, Lenis A, Skinner OD. Carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Sur Clin Nort Am 1986; 66:659-71.

28. Shah JP. Patterns of cervical lymph node metastasis from squamous carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg 1990; 160:405-09.

29. Kraus DH, Vastola AP, Huvos AG, Spiro RH. Surgical management of squamous cell carcinoma of the base of tongue. Am J Surg 1993; 166:384-8.

30. Kurtulmaz SY, Erkal HS, Serin M, Elhan AH, Çakmak A. squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: descriptive analysis of 1,293 cases. The J of Laryngology and Otology 1997; 111:531-5.

31. Amorim Filho FS, Andrade Sobrinho J, Rapoport A, Carvalho MB, Novo NF, Juliano Y. Estudo de variáveis demográficas, ocupacionais e co-carcinogenéticas no carcinoma espinocelular da base de língua nas mulheres. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 2003; 69:472-8.Table 1. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, classification according to histological grade of primary lesion.

*Without further specificationTable 2. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, classification according to tumor size and local dissemination.Table 3. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, classification according to dissemination to other areas.Table 4. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, classification according to size of primary tumor and midline invasion.

Chi-square

X2 =43.922 X2=(3 gl; 5%) = 7.815

Chi-square Distribution

T1 Vs T1,T3,T4 X2=7.946

T2,T3 Vs T4 X2=34.006

(P<0.001)Table 5. Patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue, classification according to affected area and midline invasion.

X2=5.250 X2=(7 gl; 5%)=14.067

P=0.5000

Not significant

Figure 1. Dissemination of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Base of the Tongue towards the anterior and posterior aspect of the tongue.

Figure 2. Dissemination of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Base of the Tongue towards larynx and hypopharynx.

Figure 3. Dissemination of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Base of the Tongue towards anterior and lateral aspect of the tongue.

Figure 4. Dissemination of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Base of the Tongue towards the postero-lateral aspect of the tongue.