Year: 1974 Vol. 40 Ed. 2 - (73º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 420 to 426

The Management of Orbital Complications Arising From Infections of the Frontal and Ethmoidal Sinuses

Author(s):

Rinaldo F. Canalis, M. D.,

Mark E. Krugman, M. D., and

Horst R. Konrad, M. D.

![]()

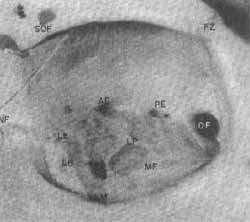

Orbital complications may develop during any phase of an inflammatory process involving the paranasal sinuses. They occur most commonly in the course of infections of the frontoethmoidal complex. Our aim is to discuss the management of orbital disease secondary to acute, sub-acute, and chronic infections of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the medial orbital wall is important to understand the pathogenesis of these complications. Medially, the orbit is separated from the ethmoidal cells by the thin lamina papyracea, lacrimal bone and the investing periosteal and mucoperiosteal layers. This wall presents the anterior and posterior ethmoidal foramina and the lacrimo ethmoidal, lacrimo maxillary, and sphenoethmoidal sutures (Figure 1). Occasionally, it may present areas of congenital dehiscence1.

Figure 1: Anatomy of the medial orbital wall. For orientation purposes note SOF: supraorbital foramen, FZ: Zygomaticofrontal suture and NF: Nasofrontal suture. Among -the structures clinically important note the lacrimoethmoidal fissure (LE) running vertically at the function of the lacrimal bone (LB) and the lamina papyracea (LP) of the ethmoid sinus; the anterior and posterior ethmoidal foramina (AE) and (PE); the vertical sphenoethmoidal suture (not marked) running immediately anterior to the optical foramen (OF); the junction of the orbital process of the maxilla with the ethmoidal bone (ME) and the lacrimomaxilfary fissure (LM).

The mode of orbital invasion varies according to the stage of the sinus infection and its initial location. The orbital venous system plays a key role in the spread of infections arising from the sinuses. This system is formed by several rich plexuses totally devoid of valves that establish a free two-way communication between the nasal mucosa, the ethmoidal cells and the orbit. Venous obstruction, phlebitis and direct entry of bacteria into the surrounding structures initiates a sequence of events that may range from mild edema to the formation of an abscess and intracranial extension. Orbital complications secondary to sub-acute and chronic sinus infections are often the sole manifestation of an exacerbation. The same steps of extension operative in the acute process may be important in their development. Other factors such as advanced osteitis, osteomyelitis, and bone destruction may predominate and alter the course of the disease. Previous surgical procedures, common in these cases, frequently disrupt the normal anatomy and can also act as moditying factors.

Report of Cases

Complications Arising From Acute Sinusitis

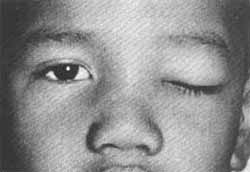

Case 1: A 7 year old boy presented with a 12 hour history of indolent left periorbital swelling (Figure 2). A respiratory infection preceeded this symptom by 48 hours.

Figure 2: Acute periorbital edema in a 7 year old boy presenting with radiographical evidence of left acute ethmoidal sinusitis (Case 1).

The patient's temperature was 370 C orally. The affected eye was only mildly painful to palpation. Vision was normal and extraocular movements were intact. The nasal mucosa was erythmatous and covered by a scant exudate. Culture of these secretions greve Diplococcus Pneumoniae. The white blood count was 11.000/ml. Plane radiographs demonstrated left ethmoidal opacifications. The patient was treated with oral Penicillin, decongestants and topical nasal vasoconstrictors. He was followed as an outpatient on a daily basis. He was symptom free five days after initiation of therapy.

Case 2: A 59 year old man was admitted to the hospital because of intestinal obstruction. A nasogastric tube was placed preceeding Laparotomy and maintained thereafter. On the third post-operatory day, he complained of left ocular discomfort. Mild edema was noted at the inner cantus of the eye which rapidly progressed to the entire orbit (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Orbital cellulitis complicating an acute suppurative process of the left ethmoid sinus. Note the marked swelling and chemosis present. The patient still has an indwelled nasogastric tube that probably played an important role in the development of his sinus infection (Case 2).

A moderate degree of proptosis and some limitation of ocular motion were present. Radiographs showed diffuse opacification of the ethmoidal sinuses. Cultures were positive for penicillinase producing Staphylococcus Aurqus. Treatment consisted of Methicillin, topical vasoconstrictors and removal of the nasogastric tube. The patient recovered promptly.

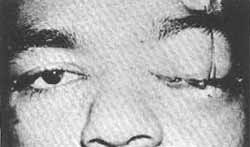

Case 3: A 23 year old man was hospitalized with a three day history of nasal congestion and pain across the dorsum of the nose. The day prior to his admission he had noted left periorbital swelling which rapidly worsened (Figure 4). He was afebrile. The nasal mucosa was red and swollen. The eye was proptosed and ocular motion was slightly decreased. Diplopia was- present on upward gaze. Visual acuity was intact. Radiographically, there was opacification of the left ethmoid and maxilfary sinuses (Figure 5). The patient was placed on intravenous Penicillin and his eye function and degree of proptosis were frequently reevaluated. Treatment did not chanqe his status. Sinus radiographs repeated 48 hours later demonstrated progression of the disease.

Figure 4: A 23 year old patient (Case 3) with a subperiostal and periorbital abscess immediately before surgical exploration.

Figure 5: Roentgenograms on Case 3 demonstrating extensive, isolated suppurative disease of the left ethmoidal air cells.

The patient was then taken to the Operating Room where through a brow incision, his left orbit and ethmoidal sinuses were explored. A subperiostal and periorbital abscess containing approximately 5 cc. of pus was found. The structures of the medial wall of the orbit, including the lamina papyracea, were intact. The sinus mucosa was edematous and polypoid in appearance. The ethrnoidal cells were exenterated and the cavity was drained into the nose. Cultures of the abscess grew Diplococcus Pneumoniae sensitive to Penicillin. Following operation, the patient recovered gradually and without sequelae.

Comment

The use of antibiotics has produced a decline in the frequency of orbital complications of acute sinus disease. However, they are by no means rare and their management requires expert clinical judgement and agressiva therapy. In the early phases, periorbital edema first appears at the inner cantus of the eye, it .rapidly extends to the superior eyelid, anal then generalizes to the periorbital. In this stage, pain is usually absent and there is no functional impairment. Case 1 exemplifies these early changes well. After cultures are taken, the patients are placed on oral antibiotics and decongestants and re-evaluated at 24 hour intervals. Initially, Penicillin is used if no allergy to the drug is present. This choice is based on the fact that most acute sinus infections are caused by a Penicillin sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus or by F`neumococci2. Exceptions to this are hospitalized patients such as Case 2 where a Penicillinase producing Staphylococcus may be suspected or young children where the incidence of Hemophilus influenzae is relatively high. Most patients will improve rapidly with this mode of therapy. Failure to respond, or lack of treatment will determine progression to a stage of frank orbital cellulitis with bacterial infiltration of the orbital contents. Pain, chemosis, fever, and a variable degree of proptosis are present. Ocular excursion is normal or slightly impaired. Vision is usually not affected. Cases 2 and 3 illustrate this more advanced form of complication. Hospitalization and high doses of parenteral antibiotics are mandatory. The general condition of the patient, degree of proptosis, and state of ocular function are followed closely. Lack of improvement or worsening of symptoms should alert the clinician to the possibility of subperiosteal or periorbital abscess and the need for surgical exploration. Case 3 is a clear example of this unfavorable evolution and is especially interesting in that failure to respond took placa in spite of the use of high doses of the appropriate antibiotics. The inability to obtain effective antibiotic levels in an area of impaired vascular supply and bacterial extravasation is likely to be the determining factor in this therapeutic failure. The integrity of the medial orbital wall as found at surgery stresses the importance of the orbital venous plexuses in the development and progress of these complications. The possibilities of further retrograde phlebitisi visual impairment and intracranial extension are present throughout the course of the infection and their avoidance is the prime responsibility of the surgeon caring for these patients.

Complications Arising From Sub-acute and Chronic Sinus Intection

Case 4: A 47 year old man presented with a four month history of severa frontal headaches and nasal congestion. His past history was remarkable in that he had repeated bouts of sinusitis when a child. His otolaryngological exaro was essentially normal, however, Roentgenograms showed total opacification of his frontal sinuses. A course of antibiotics and decongestants failed to produce improvement of his symptoms. A surgical exploration via an osteoplastic flap was then elected. Pus was present in the sinus. The mucosa was polypoid and edematous. The frontal bone appeared to be normal. The sinus mucosa was stripped and the cavity obliterated with abdominal fat. Cultures of the contents of the sinus grew Actinobaciflus Malleii and Klebsiella Aerobacter, both sensitive to Cephaloridin. The patient was maintained on this antibiotic throughout his hospitalization. He did well except for an area of circumscribed infection in the surgical wound that was healed when he was discharged on the 14th post-operatory day. Ten days later he noted swelling of his left eye which worsened rapidly. The periorbital tissues were edematous and tender, but only mildly erythematous. Vision and extraoccular movements were normal. A fluctuant area was noted in the left frontal region. The patient was again hospitalized, placed on intravenous Gentamycin and the abscess was drained. Culturas grew Hemophilus Scrophulus. The patient improved and was discharged five days after drainage only to be readmitted nine days later with an oral temperature of 390C, forehead swelling and right periorbital edema. The eye was proptotic but functionally intact. Radiographs demonstrated loss of definition of the bone flap margin and irregularity of the inner aspects of the same (Figure 6). With the presumed diagnosis of osteomyelitis of the frontal bone, the area was surgically re-explored. The anterior wall of the frontal sinus was found to be necrotic. The diseased bone was removed and the sinus collapsed. The patient was maintained on antibiotics for approximately six weeks after surgery. He has recuperated fully and is assymptomatic.

Figure 6: Osteomyelitis of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus (Case 4). Note irregular appearance of the posterior limits of the anterior sinus wall and areas of decreased density in the wall itself.

Case 5: A 30 year old stuntman was transferred from another hospital with right periorbital swelling present for six weeks. He had a history of multiple allergies, asthma and hay fever since childhood. Recently, he had needed several intranasal polypectomies and bilateral antral operations. At examination, his temperature was 39° C orally. His right eye was proptotic and inferiorly displaced. Vision and ocular motion were intact. Roentgenograms showed opacification of all sinuses and erosion of the right frontal sinus and partial destruction of the right orbital roof (Figure 7). Under antibiotic coverage, a trephine of the right frontal sinus was done and a large volume of purulent material drained. Cultures grew E. Coli sensitive to Gentamycin. The patient was then treated with this drug.

Figure 7: Pansinusitis with marked chronic changes of the frontal, sinus in Case 5. Note the indistinct limits of the voluminous frontal sinus and the area of decreased density present in the right roof of the orbit (at the left of the reader).

His acute problem resolved, the frontal sinuses were explored via an osteoplastic flap. Dehiscences were noted at the right floor and posterior walls of the frontal sinus. Pus and polyps were present and evacuated, the mucosa was entirely removed and the cavity obliterated with abdominal fat. Initially, the patient did well, however, four weeks after obliteration, the right orbital cellulitis recurred, and the trephine site spontaneous1y re-opened, and drained. Cultures again grew E. Coli, now sensitive to Chioramphenicol. The frontal sinuses were then re-explored and the infected fat implant removed. In addition, a right ethmoidectomy was performed and drainage established into the nose by means of a silastic tube. The patient was then maintained on Chloramphenicol for approximately four months. During this time, it became evident that chronic osteomyelitic changes were present at the base of his skull (Figure 8), and while further therapy was planned, he again developed right periorbital cellulitis and a periorbital abscess. The frontal sinus was once more explored and the diseased bone of the anterior and posterior tables removed. The cavity was then collapsed. The patient recovered rapidly and is now free of disease.

Comment

Most of the current complications of paranasal sinusitis are secondary to subacute or chronic infections3. Their mode of presentation, clinical course and therapeutic requirements differ considerably from complications occurring in the course of acute sinusitis. Orbital disease in these cases is usually part of other complicating factors such as osteomvelitis, pyocele formation, and longstanding allergic changes. Management is complex, longterm and requires a clear understanding of the underlying sinus problem. Of primary importance is the extent and nature of the disease affecting the sinuses.

Figure 8: Severe osteomyelitic changes of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus (Case 5). Extension into the floor and base of the skull present at exploration are not well demonstrated here.

A history of chronic sinusitis, allergies and previous operations in a patient presenting with an acute orbital process carries a guarded prognosis. It requires hospitalization and aggressive antibiotic therapy. Plane Roentgenograms are obtained on admission, though we find laminograms to define best the limits of the disease and presence of associated complications. Brain scanning, cerebral angiography, and orbital venography are useful when intracranial extension is suspected. An ophthalmologist evaluation is initially obtained and vision, degree of exophthalmos and extraocular motility are closely followed in order to evaluate progression of orbital disease to orbital venous thrombosis, orbital apex syndromeg or cavernous sinus thrombosis. Evaluation of signs of meningial and intracranial involvement is also necessary. The bacteriology of these problems is often complicated by the presence of a mixed flora, drug resistance and the need for prolonged use of potentially toxic antibiotics. In these aspects of the problem an Infectious Disease Specialist may be of invaluable help. The surgical approach to be undertaken has to be carefully planned to eradicate disease and permit drainage if maintenance of a functional cavity is considered. For disease limited to the frontal sinuses, obliteration via an osteoplastic flap appears to give satisfactory results4, 5. In complicated cases such as the ones presented, multiple accessory procedures proceeding or following the major operatory approach may be indicated. Drainage operations of the sinuses have little to offer in the longterm management of these advanced problems since re-obstruction is practically the rule in the presence of chronically ill mucosa. They play a roll in the temporary management of the seriously ill patient. Obliteration still plays an important rote though the risk of persistent infection is high and osteomyelitis is a serious hazard. When it occurs, radical bone resection and collapse are the only choices.

Summary and Conclusion

Our experience in the management of orbital complications of acute and chronic infections of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses has been reviewed. Five recent cases were used to illustrate these challenging clinical problems. There are important differences between the complications of acute sinusitis and those arising during the course of chronic sinus disease. Currently, orbital extensions of sinus infections appear to be more prevalent in the presence of chronic sinusitis or untreated acute sinusitis since the prompt use of an effective antibiotic usually cures acute sinusitis rapidly and without sequelae. In general, orbital infections secondary to acute sinusitis have the same bacteriological features of primary sinus infections. They usually represent all isolated complication and respond well to conservative measures. They carry an excellent prognosis. Conversely orbital infections occurring during the course of chronic or subacute sinusitis usually represent one of multiple complicating facets of a chronic problem. Their ultimate outlook depends on the extent of the underlying process and associated changes. Bone disease, loculated infection and irreversible mucosaˇ changes aggravate the prognosis. Management is complex and longterm and may require the assistance of specialties outside otolaryngology. The primary attack on the disease is surgical, however, a complex bacteriological picture is often the case and requires longterm, closely supervised antibiotic therapy.

Bibliography

1. Wiliamson-Noble, F. A.: Disease of the Orbit and Its Contents Secondary to Pathological Conditions of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses, Ann. Roy. Col Surg, Engl., 15:46, 1954.

2. Catlin, F. I. Et al.: Bacteriology of Acute and Chronic Sinusitis, South Med. J., 58:1497.

3. Quick, C. A. and Payne, E.: Complicated Acute Sinusitis, Laryngoscope, 82: 1248 - 1263, 1972.

4. Goodale, R. L. and Montgomery, W. W.: Experiences with the osteoplastic Anterior Wall Approach to the Frontal Sinus, Arch. Otolaryngology, 68:271-283, 1958.

5. Mozolewski, F.: Osteoplastic Approach to the Frontal Sinus a New Method Acta. Otolaryng. (Stockholm) 52: 27-30, 1960.

6. Kronschnabel, E. F.: Orbital Apex Syndrome Due to Sinus Infection, Laryngoscope, 84: 353-371, 1974.

All rights reserved - 1933 /

2025

© - Associação Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico Facial