Year: 2001 Vol. 67 Ed. 1 - (6º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 43 to 49

Myofunctional and Cephalometric Evaluation of Mouth Breathers.

Author(s):

Fabiana C. Pereira*,

Suely M. Motonaga**,

Patrícia M. Faria***,

Myriam A. N. Matsumoto****,

Luciana Y. V. Trawitzki****,

Soraia A. Lima******,

Wilma T. Anselmo Lima*******.

Keywords: mouth breathers, cephalometry, myofunctional changes, cranial morphology

Abstract:

Introduction: Mouth breathers assume new postures in order to compensate and make breathing possible. As a consequence, they develop important skeletal and myofunctional changes during facial growth. Aim: The aim óf the present study was to evaluate the changes in facial morphology detected in a group of mouth breathers compared to a group of children with the same age who were predominantly nasal breathers, as well as the myofunctional changes occurred in the mouth breather-group. Material and method: The children were evaluated by an otorhinolaryngologist to determine the breather groups (mouth, mixed or nasal), by an orthodontist who performed facial cephalometric analysis, and by a speech therapeutist for myofunctional evaluation. Thirty-five children aged seven to 10 years were divided into two groups, Le. 20 mouth breathers and 15 nasal breathers. The cephalometric changes most commonly found in mouth breathers when compared to nasal breathers were maxillary and mandible hypoplasia and increased gonial angle, with mandible rotation down and backward. Results: The most common myofunctional oral changes detected in mouth breathers were half-open lip and lower tongue position, lip, tongue and cheek hypo tonicity, and tongue interposition between the arcades during deglutition and phonation. Conclusion: The morphological changes of the facial pattern detected in mouth breathers led us to conclude that craniofacial and myofunctional alterations exist in these patients at an early age, even before the growth spurt of adolescence. These data emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary diagnosis and early treatments in order to prevent the harmful effects of long-term mouth breathing in children.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

At birth, the face is underdeveloped when compared to the cranium - during the first years of life, facial growth is responsible for the alteration of craniofacial proportion. In this phase, however, nasal breathing may be compromised by different factors, leading to extremely important facial alterations in children 15,18.

Respiratory pathway is lined with lymphoid tissue, forming the lymphatic ring of Waldeyer, consisting mainly of lingual, palatine, pharyngeal and tubarian tonsils, in addition to lymphoid tissue. This tissue us subject to hypertrophy between the age of 2 and the adolescence; the hypertrophy, associated with the small volume of airflow at this age, may result in obstruction of the airways16. This fact is more common at the pharyngeal tonsil, because of its increased size in a narrow airway. In addition, allergic rhinitis that leads to nasal obstruction may also result in mouth breathing at this age range. Among all the other affections that may be observed, these two affections are the main causes of oral breathing, in many occasions presented together.

If the child has mouth breathing during the period of facial growth, it results in posture and praxia alterations, compromising normal facial morphology14, 15.

In mouth breathers, since there is not the appropriate airflow going through the nasal fossae, the nasal mucosa is hypertrophied, pale and hypofunctioning. In addition, the nasal hypoflow leads to hypoplasia of maxillary sinuses and narrowing of nasal fossae.

Maxillary hypoplasia may be due to two factors: passage of insufficient airflow through the nasal fossae and absence of pressure of the tongue against the hard palate 14,15. It is tridimensionally represented as follows: transversally, the palate is narrow, sometimes too high (maxillary endognatia), resulting in deviation of jaw in order to stabilize the bite. Anterior-posteriorly, maxillary hypoplasia is expressed by mandibular pseudo-prognatism. Vertically, the absence of tongue pressure against the palate results in insufficient vertical, growth of alveolar processes, leading to dental infra occlusion.

In order to, have such breathing posture, the mouth breather should keep the mouth open almost all the time. It requires stretching the head forward 14,17 and it modifies muscle stimuli, resulting in bone modeling disorders during growth¹°.

Linder-Aronson¹° reported increase in anterior facial height (total and inferior), increase of the inclination of mandibular plan, facial retrognatism, mandibular hyperdivergence with rotation of growth to the posterior plan, opening of gonial angle, alterations in the axial inclinations of incisors, extension of the head and lowering of the hyoid bone. Hultcrantz 6 reported high incidence of open bite in mouth breathers, in addition to posterior-inferior rotation of mandible. Oulis16 emphasized the anterior and inferior position of the tongue, posterior and inferior rotation of the mandible and high incidence of cross bite and dental alterations (horizontal and vertical).

According to Marchesan ¹², the most common speech and articulation alterations are facial muscle hypotonia, especially of mandible elevators, alteration of lip, cheeks and supra-hyoid muscles tone, and anterior placement of the tongue at rest, modifying mastication, swallowing and phonation functions, by placing the tongue anteriorly on the two former functions and anterior and laterally on the latter function. Bianchini¹ stated that there is increased tone of perioral muscles in order to offset hypotonia of mandible elevator muscles, minimizing swallowing difficulties.

Limme9 referred that different tongue positions, based on personal experiences of praxia and gnosia, could be related to the great dimorphism observed in these children. Therefore, the tongue goes down and by propulsion it leads to mandibular hyper-propulsion, increasing the sagittal development of mandible or even mandibular prognatism; the tongue in retropropulsion leads to mandibular underdevelopment with mandibular retrognatism; anterior positioned tongue results in dental occlusion or deviations in teeth inclination, especially the incisors. The altered tongue position would also result in phonation and swallowing disorders, marking strongly the deviations present in the craniofacial growth.

Marchesan¹² reported that atypical swallowing is a consequence of bad posture and low tonicity of speech organs; according to Bianchini¹, atypical swallowing is not only a result of the factors listed above, but also of the increase in height of the anterior facial region, rotation of mandible, anterior placement of tongue, and open bite, hindering lip closure.

Nevertheless, Humphreys et al, Gwynne-Evans et al.5 and Leech8, in transversal and longitudinal studies did not observe craniofacial alterations in mouth breathers. These authors believe that the findings were a result of the difficulty in quantifying nasal obstruction and determining objectively the mode of breathing. Moreover, it is not defined how much oral breathing would be necessary to create a cause relation between nasopharyngeal obstruction and dental malocclusion.

Owing to the controversy described in the literature concerning breathing patterns and craniofacial growth, especially in children, we decided to conduct complete otorhinolaryngologic, orthodontic and speech assessment of children aged 7 to 10 years who had mouth breathing.

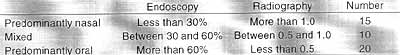

The purpose of our study was to assess facial morphology, using a cephalometric analysis of facial pattern, in a group of mouth breathing children who were aged 7 to 10 years, comparing them to children of the same age range who used to breathe through the nose. We also investigated the presence of oral myofunctional alterations in mouth breathers.TABLE 1 - Classification of children according to type of breathing pattern.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The Disciplines of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - Universidade de São Paulo, Division of Speech and Hearing Pathology Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto, FMRP - USP, and the Clinic of Orthodontics, Faculdade de Odontologia, Ribeirão Preto USP, assessed together 35 children aged between 7 and 10 years.

In the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, children were submitted to clinical, radiological and endoscopic assessment - some children refused to undergo the endoscopic exam. We assessed all anatomical alterations, such as septal deviation, hypertrophy of inferior turbinate, and size of palatine and pharyngeal tonsils.

Nasofibroscopy was performed in order to check the percentage of obstruction of the sinus by size of adenoid; paranasal sinuses x-rays were conducted to check the obstruction of the sinus by the adenoid using Cohen a Konak¹ method (comparing amplitude of airflow with thickness of soft palate, according to the description of the method), and they were divided into 3 groups (Table 1):

1) Nasal breathers: children with no evident clinical signs of nasal obstruction, endoscopy showing adenoids obstructing at most 30% of the sinus and/or radiography with airflow/palate ratio higher than 1.0;

2) Mixed breathers: children with few unimportant clinical signs of nasal obstruction, endoscopy showing adenoids obstructing between 30% and 60% of the sinus and/or radiography with airflow/palate ratio between 0.5 and 1.0;

3) Mouth breather: children with marked clinical signs of nasal obstruction, endoscopy showing adenoids obstructing at least 60% of the sinus and/or radiography with airflow/ palate ratio lower than 0.5.

The same children were submitted to cephalometric profile assessment, measuring the following angular measures, comparing growth and position of maxilla and mandible with the cranium (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Evaluated points, lines and angular measures.

SNA: intersection of lines SN (sella-nasal) and NA (nasal sub-spinal); expresses the degree of protrusion or retrusion of maxilla in relation to the skull base.

2) SNB: intersection of lines SN and NB (nasal-supramental); expresses the degree of protrusion or retrusion of the-mandible in relation to the cranium.

3) ANB: intersection of lines NA and NB; expresses the anterior-posterior relation between maxilla and mandible.

4) SNGoGn: intersection of lines SN and GoGn (Steiner mandibular plan); expresses the degree of inclination of mandibular plan in relation to the anterior base of the cranium.

5) Axis SNGn (or Y-SN): intersection of lines SN and SGn; expresses the direction of facial growth.

6) 1.SN: axial inclination of upper central incisor in relation to line SN.

7) IMPA: inclination of lower incisor and mandibular basis (Tweed mandibular plan).

8) 1.I axial inclination of incisors.

In addition to angular measures, we considered the following linear measures:

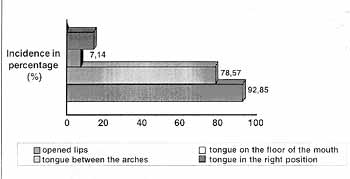

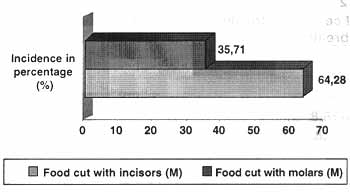

Graph 1. Incidence of myofunctional alterations found in mouth breathers concerning posture of tongue and lip.

1) MSC: palatal plan: it is the height of the first molar in relation to the palatal plan.

2) MIC: mandibular plan: it is the height of the first lower molar in relation to Steiner mandibular plan.

All findings were analyzed according to the non-parametric statistical test of Mann-Whitney.

Fourteen mouth breathers were submitted to the assessment of myofunctional characteristics conducted by the speech pathologist. There was no control group in this analysis. The studied parameters were:

1) Habit of prolonged suction (digit, bottle or pacifier), classified as those who had it for more than 2 years.

2) Lips and tongue posture.

3) Tonicity of lips (upper and lower lips), tongue and buccinator, mentalis and masseter muscles, through muscle palpation conducted by 2 observers that followed the same criteria.

4) Mastication: we gave to patients a piece of a roll to observe the cut of food with incisors and molars, and check lip closure during this action.

5) Swallowing: we observed if the subject had tongue or lip thrusting during swallowing.

6) Phonation: we observed if the subjects had tongue thrusting during phonation and which phonemes were affected by it.

These data were analyzed according to percentage of frequency among mouth breathers.

RESULTS

ENT evaluation

At clinical and endoscopic exam, we excluded the children who had mouth breathing and alterations that were not pharyngeal tonsil hypertrophy, but associated with it, such as allergic rhinitis, septal deviation and palatine tonsil hypertrophy.

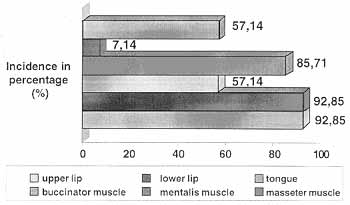

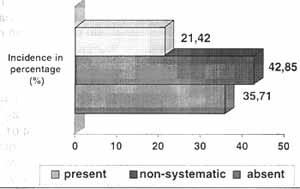

Graph 2. Incidence of myofunctional alterations found in mouth breathers concerning reduced tonicity.

We evaluated 45 children - 15 of them were predominantly nasal breathers and 30 were mouth breathers, showing pharyngeal tonsil hypertrophy as the only cause of nasal obstruction. Children were aged between 7 and 10 years and 18 were girls and 17 were boys.

They underwent endoscopy and sinus radiography and were divided into 3 groups: nasal breathers, mild or mixed mouth breathers and moderate to severe mouth breathers (Table 1). Children in group 2 were excluded from the analysis to enable clear differentiation of groups.

Myofunctional evaluations

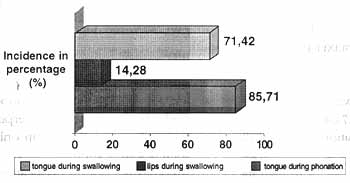

Results concerning myofunctional characteristics of mouth breathers are described in Graphs 1 to 5.

Regarding habits, the 14 mouth breathers (that belonged to group 3) presented 11 (78.57%) who used a bottle, 6 (42.85%) who used a pacifier and one child (7.14%) who had sucked the thumb for more than 2 years. Only 2 of them (14.28%) had no associated habit for a prolonged time.

Among mouth breathers, 13 (92.85%) maintained open lips; in 11 (78.57%) the tongue remained on the floor of the mouth, and in one (7.14%), it remained between the arches; two children (14.28%) had the appropriate tongue posture (Graph 1).

Lip hypotonia (upper and lower lips) was observed in 13 (92.85%), whereas tongue hypotonia was found in 8 (57.14%) mouth breathers. As to muscles, we observed hypotonicity of buccinator in 12 (85.71%) cases, of masseter in 8 (57.14%) and of mentalis in only one case (7.14%) among mouth breathers. Eleven children (78.57%) presented the expected tonicity (Graph 2).

Graph 3. Incidence of myofunctional alterations found in mouth breathers concerning cut of food during mastication.

Out of the total number of children, nine (64.28%) mouth breathers cut the food with the incisors, and five (35.72%) with molars (Graph 3). Lip sealing was observed in 5 children (35.72%), non-systematic sealing in six cases (42.85%) and not present in three children (21.42%) (Graph 4).

During swallowing, there was tongue thrusting in 12 cases (85.71%) and lip thrusting in two cases (14.28%). As to speech, we observed tongue projection for linguodental phonemes in 10 (71.42%) subjects; the most common speech mistakes were: /n/ /l/ /t/ and /d/ in 90% and /s/ and /z/ in 60% of the children.

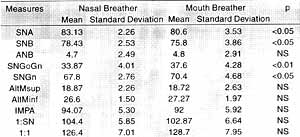

Cephalometric Assessment

The results found in each studied group (mouth and nasal breathing), as well as their comparisons are shown in Table 2.

As we can see, as to anterior posterior growth we may conclude that there was statistically significant difference (p+0.05) between values of SNA (that evaluates the growth of maxilla in relation to the skull base) and SNB (that evaluates mandibular growth based on the skull base); however, there was no difference in ANB (that compares the growth of mandible and maxilla) between the two populations.

As to vertical growth, there was statistically significant difference between the populations in both parameters, SNGoGN (inclination of mandibular plan): p 0.01 and SNGn (direction of facial growth): p 0.05.

However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups when it came to position and inclination of teeth, both for incisors and molars.

Graph 4. Incidence of myofunctional alterations found in mouth breathers concerning labial closure.

Graph 5. Incidence of myofunctional alterations found in mouth breathers concerning tongue interposition during swallowing (D) or phonation (F).

DISCUSSION

Myofunctional alterations

According to Bianchini¹, Felicio³, Marchesan¹³ and Weckx and Weckx18, a mouth breather subject has a head and neck posture that is different from that of a nasal breather, in addition to presenting difference in soft tissues, such as the lips (normally opened) and the tongue (generally on the floor), necessary to force the airflow into the oropharynx and not the nasal fossae.

Alterations of positioning of facial soft tissue for mouth breathing lead to alterations in tonicity of lips, tongue and mastication muscles1,13. In our study, tonicity of lips and facial muscles was very reduced. Hypotonicity of tongue was frequent (57.14%), but less than lips (92.85%) or cheeks (85.71%) hypotonicity. This fact may be due to prolonged use (more than 2 years) of milk bottles and pacifiers by most of the children.TABLE 2 - Mean values and standard deviation of cephalometric measures in nasal breather and mouth breather patients.

Limme9, Weckx and Weckx18 and Oulis16 described praxia alterations in mouth breathers, among them tongue thrusting¹², as well as lip interposition during swallowing and phonation. In the present study, tongue interposition was frequent both- for swallowing (85.71%) and phonation (71.42%), especially for linguodental phonemes; lip interposition during swallowing was less frequent, present in only 14.28% and it was not considered significant.

The high incidence of lip closure during mastication, systematic or not, may be explained by the fact that the patient was being observed by the examiner, automatically occluding the lips. However, the fact that it was non-systematic in most children shows us that this is another key praxia alteration in the study, compatible with the data from Marchesan¹².

Cephalometric alterations

Limme9 and Linder-Aronson¹° said that soft tissue praxia and tonicity alterations, consequences of the wrong posture of mouth breathers, result in disorders of the balance defined by the forces of the facial bones, which modify the pattern of craniofacial growth.

We may state, based on these results, that the group of mouth breathers when compared to the control group had a reduction in growth of both maxilla (SNA) and mandible (SNB) in relation to the skull, but there was no difference between maxilla growth in relation to mandible (ANB).

The reduction in maxillary growth may be due to three factors:

1. Inadequate airflow passage through the nasal fossa, resulting in nasal and paranasal sinuses hypoplasia;

2. Reduction of facial muscle tonicity, especially of buccinator muscle;

3. The reduction of the pressure made by the tongue against the palate.

These factors are known to stimulate maxillary growth in the three planes: transversal, anterior-posterior and vertical. It is important to point out that using SNA we can evaluate only the anterior-posterior growth of the maxilla, but not its transversal and vertical axes .

Reduced mandibular growth at the sagittal plan may be a result of positioning and tonicity of facial and tongue muscles, once the hypotonicity and lower posture of tongue, observed in the present study, promoted reduction of mandibular growth stimuli. In addition, another characteristic that could support the lack of stimuli to mandibular growth would be incorrect swallowing model. In the present study we observed that the growth pattern of mandible was altered, with predominance of vertical growth as opposed to sagittal growth (reduced SNB), a characteristic that was detected by the angular measures SNGoGn and SNGn.

As to anterior-posterior position between maxilla and mandible (ANB) there was no statistically significant difference between the groups of nasal and mouth breathers, because anterior growth was reduced in both maxilla and mandible.

A possible explanation for this finding would be the lower position of the tongue (floor of the oral cavity), which promotes underdevelopment of the mandible, following the underdevelopment of the maxilla.

The predominance of vertical growth of the face, associated with more inclination of the mandibular plan in relation to the anterior base of the cranium was more evident in mouth breathing children. The difference between the two groups, regarding mandibular growth with posterior-inferior rotation, was a statistically significant difference. This characteristic occurs because mouth breathing cause hypotonia of facial muscles and, consequently, lowering and posterior rotation of the mandible. It is important to point out that there was no increase in the anterior growth of mandible (reduced SNB), but rather exacerbated posterior rotation associated with more inclination of mandibular plan in relation to anterior basis of skull.

In previous studies, Linder-Aronson¹°, Limme9 and Oulis16 mentioned alterations in the inclination or position of teeth, incisors (more commonly) or molars. In our study, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in any tooth-related measures, be it incisor or molar. This fact may explain the high incidence of anterior teeth used to cut food, because overjet, common in mouth breathers, was not noticed in this group of children.

CONCLUSION

Cephalometric alterations more commonly found in mouth breathers are related to maxillary and mandibular hypoplasia and to the predominance or facial vertical growth, because of increased rotation of mandible back and downwards.

As to myofunctional alterations, the most common were open lip posture and tongue on the floor of the mouth, lip, tongue and mastication muscles hypotonicity and tongue interposition during swallowing and phonation.

These skeletal facial alterations were found in mouth breathing children aged between 7 and 10 years and guided us to the conclusion that there are myofunctional and craniofacial alterations in these age range patients, even before the growth spurt of adolescence. This fact reinforces the importance of having multidisciplinary diagnosis and early treatment to prevent the harmful effects of prolonged mouth breathing in children.

REFERENCES

1. BIANCHINI, E. M. G. - A cefalometria nas alterações miofuncionais orais: diagnóstico a tratamento fonoaudiológico. Carapicuíba- pró-Fono, São Paulo, 1995: 107.

2. COHEN, D.; KONAK, S. - The evaluation of radiographs of the nasopharynx. Clin Otolaryngol, 10: 73-78, 1985;

3. FELÍCIO, C. M. - Fonoaudiologia aplicada a casos odontológicos: motricidade oral a audiologia. Ed Pancast, São Paulo, 1999: 243.

4. FREEMAN, G. L.; JOHNSON, S. - Allergic diseases in adolescents. I: description of survey: prevalence of allergy. Am J Dis Child, 107: 549-559,1967;

5: GWYNNE-EVANS, E.; BALLARD, B. C. - Discussion on the mouth-breather. Proc R Soc Med, 51: 279-285, 1959;

6. HULTCRANTZ, E.; LARSON, M.; HELLQUIST, R. et al. The influence of tonsillar obstruction and tonsillectomy on facial growth and dental arch morphology. Int. J. Ped. Otorhinolaryngol., 22:125-134,1991;

7. HUMPHREYS, H. F.; LEIGHTON, B. C. - A survey of anteroposterior abnormalities of the jaws in children between the ages of two and five and a half years of age: Br. Dent. J., 88: 3-15, 1950;.

8. LEECH, H. L. - A clinical analysis of orofacial morphology and behavior of 500 patients attending an upper respiratory research clinic. Dent. Practit., 9: 57-68, 1958;

9. LIMME, M. - Consequences orthognatiques et orthodontiques de la respiration buccale. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. belg., 47: 145-155,1993;

10. LINDER-ARONSON, S. - Adenoids: Their effects on mode of breathing and nasal airflow and their relationship to characteristics of the facial skeleton and the dentition. Acta Otolaryngol Supp 265: 1-132,1970;.

11. LINDER-ARONSON, S. - Naso-respiratory function and cranio-facial growth. In: Monograph n° 9, Cranio-facial Growth Series, p. 87-119. Ed. J. A. Mc Namara, Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1979.

12. MARCHESAN, I. - Avaliação a terapia dos problemas da respiração. In: Marchesan I et al. Fundamentos em Fonoaudiologia: aspectos clínicos da motricidade oral. Ed Guanabara Koogan, São Paulo, 23-26, 1998;

13. MARCHESAN, I.; KRAKAUER, L. H. - A importância do trabalho respiratório na terapia miofuncional. In: Marchesan I et al. Tópicos de Fonoaudiologia vol II. Ed. Lovise. São Paulo, 155-160 1995;

14. MORRISON, W. W. - The relationship between nasal obstruction and oral deformities. Int. J. Orthod., 17 453-458. 1931;

15. O'RYAN, F.; GALLAGHER, D. M.; LABANC, J. P.; EPKER, B. N. - The relation between nasorespiratory function and dentofacial morphology: a review. Am. J. Orthod., 82(5): 403-410, 1982;

16. OULIS, C. J.; VADIAKAS, G. P. et al. - The Effect of hypertrophic adenoids and tonsils on the development of posterior crossbite and oral habits. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 18-(3): 197-201, 1994;

17. SOLOW, B.; GREEVE, E. - Cranio-cervical angulation and nasal respiratory resistance. In: Monograph n° 9, Cranio-facial Growth Series, p. 87-119. Ed. J. A. Mc Namara, Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1979.

18. WECKX, L.; WECKX, L. - Respirador bucal: causas a conseqüências. Rev. Bras. Med., 52: 863-74 1995;

*Resident Physician of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto, FMRP - USP.

**Master studies under course at the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto, FMRP - USP.

***Master studies under course at the Discipline of Orthodontics, Faculdade de Odontologia, Ribeirão Preto - USP.

****Ph.D. Professor of Faculdade de Odontologia de Ribeirão Preto - USP.

*****Assistant Speech and Hearing Pathologist of the Division of Speech and Hearing Pathology of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto, FMRP - USP.

******Speech and Hearing Pathologist graduate at the Division of Speech and Hearing Pathology of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto, FMRP - USP.

*******Ph.D. Professor of the Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery at FMRP - USP.

Study presented at 35° Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, which received a special citation.

Article submitted on August 15, 2000. Article accepted on October 20, 2000.