Year: 2001 Vol. 67 Ed. 1 - (5º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 36 to 41

Intracranial Complication of Sinusitis.

Author(s):

Norma O. Penado*,

Andrei Borin**,

José E. S. Pedroso***,

Jurandy M. S. Pessuto****.

Keywords: sinusitis, intracranial complications, cerebral abscess, subdural empyema

Abstract:

Introduction: Although there is a great development in diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis, the intracranial complications are still present. Objective: The objective of this study is to demonstrate the importance to always keep in mind the possibility of those complications. The early diagnosis and the best treatment not only of the intracranial complication, but also the sinunasal primary focus are necessary to minimize the sequelae and to reduce the permanence inside the hospital. Material and method: In research realized between 1991 and 1999 in our Service we detected 11 cases of intracranial complications related to acute or chronic sinusitis. In this retrospective study we discriminate the otorinolaryngology and neurosurgery diagnosis, results of cultures, treatment and sequelae. Literature revision was compared with our cases.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Infectious acute or chronic sinusitis is very frequent and generally has a benign behavior. However, it is an entity that has potential complications when the disease spreads into adjacent structures. The most frequent sinunasal complication involves the orbit (cellulite and intraorbital abscess), and secondly, the intracranial region 1,7.

Courville has already described the potential of intracranial complications5 in 1944. Bluestone and Steiner reported an 11%, incidence of intracranial complications in 38 patients admitted to the hospital with frontal sinusitis in 1965¹. Currently, despite technological advances in diagnosis and treatment, either clinical or surgical, we still observe a large number of complications, and an estimated incidence of 3.7% reported by Clayman et al.¹. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention define prognosis of these patients, reducing both morbidity and mortality.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

We conducted a retrospective study of cases managed by our service who had intracranial complications related with acute or chronic sinusitis in the period between January 1991 and December 1999. We analyzed medical files aiming at collecting data about: age, gender, etiological diagnosis, result of bacterial cultures, antibiotic therapy, ENT and neurosurgical procedures used, length of hospital stay, sequelae at discharge and other relevant information. We conducted a review of the literature in the past 10 years.

RESULTS

In the eight-year period there were 11 cases of intracranial complications (ICC) related with chronic or acute sinusitis, as shown in Table 1.

The age of patients ranged from 9 to 37 years, mean age of 18 years. There was a predominance of male patients (10 cases) and one female patient. As to progression of sinusitis, we found a balanced situation - 7 chronic cases and 5 acute ones.

The most frequent ICC was cerebral abscess found in 8 cases (six frontal, one fronto-parietal and one temporoparietal cases), followed by subdural empyema in 4 cases.

Six patients presented sterile cultures. In cases with positive culture, we found Staphylococcus aureus (3), Streptococcus viridans (2) and Enterococcus (one associated with Staphylococcus aureus).

Antibiotic therapy employed in all cases combined vancomycin, ceftriaxone, metronidazol, amicacyn and imipenem.

In seven cases, the neurosurgical procedure of drainage via cranial trepanation was performed, and in two patients it was repeated. In four cases no surgical procedures were performed. Two cases were submitted to intervention of the primary sinusal focus, one with maxillary punch and the other with bilateral sinusectomy (anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy, plus middle antrostomy and opening of the frontal recess).

Nine cases out of 11 were discharged within 14 to 60 days (mean of 34.8 days) and two cases had sequelae of convulsive seizures. The other two patients died, one because of ventriculitis and the other because of recurrence of acute myeloid leukemia (m2), non-responsive to chemotherapy.

Two young patients were drug users, with negative HIV, and another manifested pharmacodermia to vancomycin during treatment.

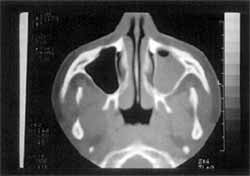

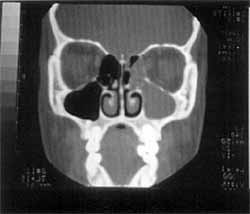

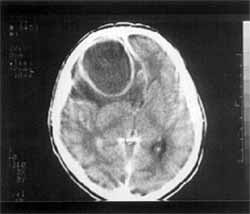

We presented some CT scans of patients in Figures 1 to 6.

DISCUSSION

Complications of acute or chronic sinusitis are defined as any extension of the local disease into the adjacent structures. Both chronic and acute sinusitis pray result in intracranial complications (ICC), but the literature reports a 75% predominance of acute sinusitis¹ ³. In our series, we found a balance between the two, showing a trend towards the predominance of chronic processes

The most common complication of sinusopathy is in the orbit, followed by intracranial compromise¹. The incidence of ICC in sinusopathy is difficult to assess because there is no estimate of its occurrence in the population. However, most cases of acute or chronic sinusitis that require non-elective hospitalization are due to orbital complications (first cause) and intracranial complications (second cause). Gianonni et al.³ found that 5.9% of all cases of meningitis and intracranial abscesses were related with sinusitis. Other authors1, 5 reported that of all sinusitis that require non-elective hospitalization, 3.0 to 3.7% of them were caused by ICC.

As to pathophysiology of ICC in sinusopathy, they may occur by two different paths: (1) retrograde thrombophlebitis of veins that connect the paranasal sinuses and the brain and are not valves (diploic and communicating veins), or (2) direct extension of the infectious pathology through, the anatomical paths, with dehiscence (traumatic or congenital) and erosion of sinus wall and existing foramens³.TABLE 1 - Patients with acute and chronic sinusitis associated with intracranial complications

Figure 1. CT scan, at coronal section, showing pansinusitis.

Figure 2. CT scan, at axial section, showing subdural empyema

Figure 3. CT scan at axial section, showing subdural empyema

Figure 4. CT scan at axial section, showing left maxillary sinusitis

There are at least 5 types of ICC that may be present in the same patient:

1) Cerebral abscess is reported as the most common type of ICC; in sinusal cases, it is mainly related to the frontal lobe¹ ³, and, we observed the same in our series. The clinical picture starts with cerebritis, clinically associated with headache. Next, there is a quiescence and asymptomatic phase of coalescence until it defines its classic image of expansion into the cerebral parenchyma, resulting in headache and leth argy. The final phase is intraventricular or subdural rupture, dramatically progression to coma or death. They may be treated clinically or by neurosurgical drainage, the preferred approach by most authors¹ ³.

2) Meningitis is reported as the second most common cause of ICC¹. Generally speaking, management is clinical³. We should keep in mind that when performing CSF punch as an attempt to define the diagnosis before we exclude endocranial hypertension there is the risk of herniation ¹.

3) Epidural empyema is rarely referred, although it has a high prevalence in some series³. It requires surgical drainage. In our series, we did not detect this affection.

Figure 5. CT scan, at corona! section, showing maxillary and ethmoidal sinusitis

Figure 6. CT scan, at axial section, showing antral abscess.

4) Subdural empyema generally has multiple locations; some authors believe that its occurrence is correlated with a high risk of sequelae³. In some articles, it is referred as the most prevalent complication4. In our series it was present in 4 cases out of 11.

5) Venous sinus and cavernous sinus thrombosis are rare; nevertheless, they are the most severe ICC³. We detected only one case in our series.

The predominance of male cases may be found in all studies, ranging from 60 to 78% 1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The same was observed in our series, with a ratio of 10:1. As to age range, we noticed that the literature reported a high incidence of younger people in the second and third decades of life1,3,6,7, followed by a second peak in the fifth and sixth decades³. This fact has not been fully explained yet but it is thought that it may be due to the peak of vascularization and sinusal growth that takes place in this population 1,5. The same was noticed in our series, mean age of 18 years, even with the presence of a 37-year-old patient who classified away from standard deviation.

Clinically, in addition to signs of sinusopathy, such as anterior and posterior rhinorrhea, cough and nasal obstruction, we should point out the presence of fever and late signs, such as vomiting, lethargy, mental confusion, convulsive seizures, neck rigidity, hemiparesis and coma. In most cases, patients have already followed a routine treatment for sinusitis but present a bad evolution of the case, with fever and headache, which are the triggering elements to start investigating ICC1,3,7. Whether there is leukocytosis or not does not seem to be important for the diagnosis¹. Adjuvant factors, such as diabetes, renal failure and allergic rhinitis may be noticed in up to 42% of the cases¹.

Initial imaging studies are CT scans, with or without contrast¹ ³. However, it may initially fail. Therefore, if patients still manifest clinical suspicion, they should repeat CT scan or undergo MRI, which seems to be more sensitive to early diagnosis of small cranial affections 2,7.

In general, authors advocate surgical treatment of sinusal focus as an attempt to reduce treatment duration and the risk of sequelae 1, 3, 4, 5. We may employ radical procedures, such as exenteration or cranialization of frontal sinus, or conservative approaches, such as endoscopic surgery, the main trend today.

We found data concerning length of hospital stay only in the study conducted by Gianonni³, with a mean of 31 days, close to our mean of 34.8 days. However, in our series, only a small number of sinusal interventions were performed (2 in 11), differently from most other studies.

The antibiotic therapy initially recommended by the literature is an association of a third generation cephalosporin; metronidazol and vancomycin3,5, and it is reviewed after the result of the culture and maintained for 3 to 8 weeks3, 5; it starts with endovenous medication and progresses to oral administration as the patient recovers. A large number of germs have been described but we may list the. predominance of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, Haemophylos influenza and other gram-negatives and anaerobes 3,4,5. Studies show that 21% to 50% of the cultures may be negative1,6,7. Our results were similar to these, with a high rate of negative cultures, probably because patients were already under antibiotic treatment when we collected the culture samples. Despite the fact that nasal swab culture is worthless, cultures obtained by nasal punch, sinusotomy and paranasal sinuses lavage have good correlation with the culture obtained from ICC drainage 6.

Sequelae, such as ataxia, convulsive seizures, cranial nerve paralysis and aphasia, are present in 25% to 40% of the cases1, 3, 4. Mortality is rare, but present; in our service, it was 18%. However, in one of the cases, it was caused by recurrence of leukemia (underlying disease) and not ICC. Nevertheless, we plan to have a more aggressive approach in future cases.

CONCLUSION

We concluded that:

1) despite being rare, ICC caused by sinusopathy are present in our days with considerable morbidity and mortality; they should be considered emergency cases and managed with multidisciplinary aggressive treatment.

2) the group that is most exposed to ICC resultant from sinusopathy are male young people below 20 years of age.

3) patients generally present nonspecific symptoms and the ENT should be careful when treating cases of sinus pathology that do not respond to clinical treatment and manifest fever and headache.

4) CT scan is the main complementary exam for diagnosis, but it may fail in the initial phase; it should be repeated if the clinical hypothesis of ICC still persists.

5) initial antibiotic therapy employed in such cases should involve third generation cephalosporin, metronidazol and vancomycin; considering the most frequent microorganisms in these complications, the therapy is later adjusted to attack the identified germs, if possible.

REFERENCES

1. CLAYMAN, G. L.; ADANMS G. L.; PAUGH, D. R.; KOOPMANN JR., C. F. - Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institutional review. Laryngoscope, 101: 234-9, 1991

2. CONLON, B. J.; CURRAN, A.; TIMON, C. V. - Pitfalls in the determination of intracranial spread of complicated suppurative sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 110: 673-5, 1996

3. GIANNONI, C. M.; STEWART, M. G.; ALFORD, E. L. Intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope, 107: 863-7, 1997

4. JONES, R. L.; VIOLARIS, N. S.; CHAVDA, S. V.; PAHOR, A. L. - Intracranial complications of sinusitis: the need, for aggressive management. J. Laryngol. Otol., 109: 1061-2, 1995

5. LERNER, D. N.; CHOI, S. S.; ZALZAL, G. H.; JOHSON, D. L. - Intracranial complications of sinusitis in childhood. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 104: 288-93, 1995

6. MORTIMORE, S.; WORMALD, P. J.; OLIVER, S. - Antibiotic choice in acute and complicated sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 112: 264-8, 1998

7. ROSENFELD, E. A.; ROWLEY, A. H. - Infections intracranial complications of sinusitis, other than meningitis in children: 12-year review. Clin. Infec. Dis., 18: 750-4, 1994

** Doctorate Degree in Medicine at Escola Paulista de Medicina/UNIFESP.

** Master Degree in Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery under course at Escola Paulista de Medicina/UNIFESP.

*** Master Degree in Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery at Escola Paulista de Medicina/UNIFESP.

**** ENT Physician.

Study presented at 35° Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, which received a special citation.

Affiliation: Escola Paulista de Medicina- Universidade Federal de São Paulo - Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Human Communication Disorders.

Address for correspondence: Norma Penido - Rua Rene Zanluci, 160 - Apt° 131 - 04116-260 São Paulo /SP - Tel: (55 11) 5573-1388 - Fax: (55 11) 5081-4451.

Article submitted on August 15, 2000. Article accepted on October 20, 2000.