Year: 2004 Vol. 70 Ed. 1 - (2º)

Artigo Original

Pages: 14 to 23

Histopathology of maxillary sinus lamina propria in chronic rhinosinusitis

Author(s):

Sabrina Maria de Castro Sarreta 1,

João Vicente Dorgam 1,

Bruno Beltrão de Souza 1,

Maria Dolores Seabra Ferreira 2,

Valder Rodrigues de Melo 3,

Wilma T. Anselmo-Lima 4

Keywords: chronic rinossinusitis, histopatology, mucosa, surgery

Abstract:

Chronic rhinosinusitis is defined in a simplified manner as chronic inflammation of the rhinosinusal mucosa. Aim: In an attempt to understand the reason for treatment failure. Study design: Case-control. Material and method: We decided to study the ultrastructural inflammatory changes detected in the lamina propria of the maxillary sinus of 13 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasosinusal polyposis submitted to surgical treatment. Biopsies of the superolateral wall of the maxillary sinus were obtained from these patients during the surgical act and, after preparation, were observed by transmission electron microscopy. Results: Analysis of the data obtained showed five patterns of inflammatory response in the lamina propria studied. Acute inflammatory process - 1 case; non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory process - 5 cases; chronic inflammatory process - 2 cases; disorganized inflammatory process - 4 cases; indeterminate inflammatory process - 1 case. Analysis of the results showed that the lamina propria of the maxillary sinus of these patients was infiltrated with inflammatory cells without the predominance of any particular cell element. Glandular elements were not observed in the cases studied and fibrosis was noted in almost half of them, of varying intensity and preferentially localized immediately below the epithelium. Conclusion: In the situation observed the inflammatory process did not follow the normal stages of evolution and showed marked disorganization, with difficulty in progressing to resolution of the picture, thus explaining the difficulties of patients refractory to clinical and surgical treatment.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CR) associated with nasosinusal polyposis (NP) is a disease that impairs the quality of life of millions of people all over the world. Despite the advance obtained in clinical and research areas, its exact pathophysiology is still unknown. Inflammations are reactions to vascularized connective tissues, morphologically characterized by the discharge of liquids and blood cells into the interstitium. The essential morphological element in inflammation is cell exsudate. Physical, chemical or biological aggressors can trigger an inflammatory process. Since it is a dynamic process, its morphological aspects modify with time 1.

The pathological agents that act over the tissues and induce release of substances are named mediators, which act on the existing receptors of microcirculation and leukocyte cells, producing hemodynamic affections and plasma exsudate, and blood cells into the interstitium. The action of the inflammatory agent can produce tissue damage. When the action of the agent is over, mediator release is reduced, microcirculation recovers the original hemodynamic status and liquid and exsudated cells go back to the blood circulation, normally through lymphatic vessels. Depending on the extension of the tissue lesion and the affected organ, there are healing and regeneration phenomena 1.

There are inflammatory agents that can maintain inflammation for a long time, since they act repetitively and are difficult to eliminate or because they induce immune responses to antigens. Under such circumstances, inflammatory responses persist as a result of continuous generation of mediators that stimulate cell exsudate. After some time, there is connective and vascular tissue neoformation to repair destructive lesions, whereas exsudate cells suffer many affections. Inflammatory reaction takes a chronic course and can last variable periods of time, normally inducing progressive lesions 1, 2, 3. The inflammatory process can be divided into stages or steps, one after the other, but many times there is overlapping during the process. The stages are: a) irritation; b) vascular affections; c) plasma and cell exsudate; d) degenerative and necrotic lesions; e) connective and vascular repairing proliferation, and in chronic cases, f) modifications of the exsudate cells. The capacity to repair inflammatory lesions depends on the type of inflammation and genetic elements of subjects. In persistent chronic inflammations, the repairing phenomena take place at the same time as exsudative, changing and productive phenomena, making part of the whole process 1.

The modifications of the exsudate cells after migration to the interstitium represent a productive phenomenon of inflammation. They are more easily observed in chronic cases and normally are associated with repairing phenomena 1.

Among exsudated cells, polymorphonuclear and eosinophils have very short life, and when it comes to inflammatory focus, they have already suffered the whole differentiation process, reason why they die some few hours after the exsudate. Lymphocytes of inflammatory focus can suffer differentiation. Lymphocytes T can proliferate and be activated acquiring the morphological aspect of immune-blast cells; lymphocytes B differentiate into plasmocytes, which are occasionally very numerous in some inflammations. These transformations indicate that there is effective participation in cell immune and humoral response in the inflamed tissue and that it influences the progression of inflammations 1. Monocytes accumulate in the interstitium attracted by chemotactic factors and then they are activated, transforming into macrophages with greater phagocytarian and microbiocide power. The accumulation of macrophages in the inflammatory focus is owed to the persistence of chemotactic stimuli. The macrophages produce the main tissue lesions in chronic inflammations, both by harmful action of free radicals produced and the enzymes excreted, as well as production of growth factors for endothelium and fibroblasts, which induce healing connective-vascular neoformation 1.

Endothelial cells are activated in chronic inflammations, especially in those related to immune mechanisms. As a consequence, they expose the membrane of adhesion molecules necessary for exsudation of leukocytes to chemotactic stimuli generated. Mast cells of the connective tissue can increase the number of chronic inflammations - by unknown mechanisms - and little is known about their role in these inflammations1,2,3.

The purpose of the present study was to conduct an ultrastructural histological assessment of maxillary sinus lamina propria of patients with CR associated with NP to better understand the progression of the inflammatory process in this pathology.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study group comprised 13 patients who had CR associated with NP, seen in the Ambulatory of Rhinosinusitis of our discipline. There were six male and seven female subjects. Ages ranged from 11 to 73 years, mean age of 43.23 years. The control group comprised 4 cadavers submitted to necropsy by the Service of Death Investigation, Department of Pathology, F.M.R.P-USP, with no previous history of rhinosinusitis and non-infectious cause of death. When submitted to nasofibroscopy, they did not present anatomical abnormalities or respiratory pathology suspicions.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, HCFMRP-USP, as provided by process number 1930/97, and we included only patients with CR associated with NP, refractory to any and all clinical treatment, submitted to surgical treatment by the same team of Rhinosinusitis. All patients presented paranasal sinuses CT scan with 50 to 100% of the maxillary sinuses occupied by mucous thickness and/or effusion and/or polyps. Tomographic opacification extended to ethmoid, sphenoid and frontal sinuses at variable degrees. We excluded patients with other diseases correlated with NP, such cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary diskinesia, immunodeficiency, acetyl-salicylic acid intolerance, and severe asthma.

Maxillary sinus mucosa was collected during the surgical act, when patients were under general anesthesia in the operating room after cleaning of maxillary sinus. After ostium opening, we removed secretion, cysts and/or polyps; biopsy was conducted in the thickened mucosa of the superior-lateral wall with a curved Blakesley-Wilde clamp, preserving as much as possible the upper portion. The same was taken for fixation in a solution of glutaric aldehyde at 3.0% in Sorensen buffer for 3 to 4 hours. The samples directed to test under transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were divided into fragments that were even smaller and after being washed with buffer, they were soaked in a solution of osmium tetroxide at 1.0% in a Sorensen buffer of 0.1 Molar for 2 hours at 4o C of temperature. Dehydrated, fragments were infiltrated and included in Araldite Resin 6005, sectioned with an ultra-microtome (Reichert UltraCut S) at initial thickness of 0.5 micrometer and mounted in histological slides. The sections were stained with toluidine blue solution at 1.0% in borax and kept for light microscopy. After analysis and selection of sections of fragments to light microscopy (LM), the blocks were adjusted and submitted to ultra-fine section (60-70 nanometer) that were recovered in copper grids, and submitted to a process of contrast with uranil acetate and lead citranate, observed and electro-photographed with Microscope Philips 208 operated at 80 Kv in Kodak 4489 plates at variable magnifications. Lamina propria of maxillary sinus of each grid was assessed concerning general characteristics and distribution of cellularity.

Semi-fine sections stained with toluidine blue served as the basis for the LM study. Based on them, we made the classification of epithelial type of mucous layers based on number of cell layers (simple, stratified or pseudo-stratified) and type of most superficial cell (squamous, columnar). They were photomicrographed with a photomicroscope Zeiss with objectives Apo 40 or PlaApo 63 with Kohler light.

RESULTS

We studied the maxillary sinus lamina propria of four cadavers as control group and 13 patients in the study group using TEM. Many samples of each cadaver were exhaustively analyzed. The lamina propria of the delicate basal membrane was very thin, comprising loose tissue with some spread leukocytes. Next we describe the findings of each patient in the studied group.

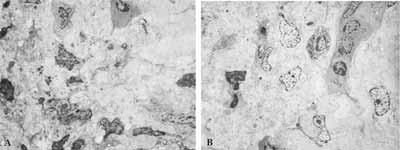

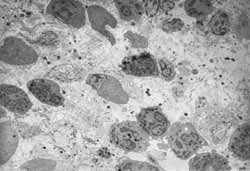

Case 1: Chronic inflammatory process (late response). We detected marked aggression to the tissue, with diversity and abundance of cell figures tending to mononuclear predominance and absence of allergic process representatives. We observed presence of elements of destruction and cleaning and fibrosis of lamina propria close to the epithelium (Figure 1).

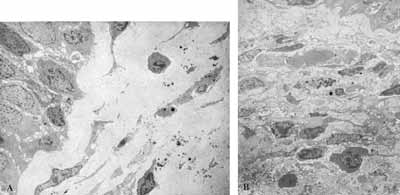

Case 2: Indeterminate inflammatory process. There was great diversity of the picture, which presented areas at different stages of inflammatory process together with normal areas. We clearly observed lamina propria fibrosis. We did not see any inflammatory infiltrate cell predominating over the others (Figure 2).

Case 3: Non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory process. The inflammatory process moved towards chronicity and resolution of processes, with fibrosis present in the lamina propria. The interstitium presented many cell debris. There was no predominance of a cell element over the others (Figure 3).

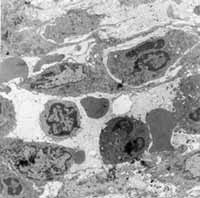

Case 4: Acute inflammatory process. There was marked predominance of neutrophils among the inflammatory cells, with rare elements of chronic process. There were few and discreet areas of fibrosis seen in this case (Figure 4).

Case 5: Non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory process. We found in this case large amounts of eosinophils and fibroblasts that were extremely activated. The response to intercellular elements pointed towards resolved chronic inflammatory picture, whereas the response to cell elements showed acute inflammatory picture (Figure 5).

Case 6: Non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory process. In this case, we observed a great diversity of cell population, without predominance of any type of inflammatory cell (presence of macrophage, plasmocyte, rare lymphocyte and absence of neutrophil) and absence of interstitial organization. There is presence of cell debris areas disseminated and alternated with areas of scarce cell population (Figure 6).

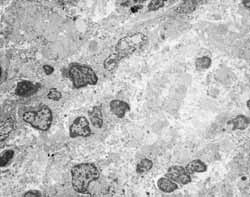

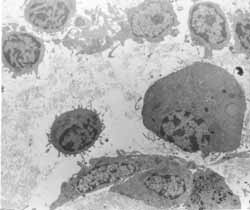

Case 7: Disorganized inflammatory process (anarchical). Acute and chronic inflammatory processes were present simultaneously in this case. It was observed that the cell population of the allergic process as well as of the inflammatory process was mixed together, without any predominant cell (Figure 7).

Case 8: Non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory process. We observed marked cell diversity, with presence of acute and chronic elements of inflammatory process. There was no predominance of cell elements over the others. The area of lamina propria close to the epithelium was intensively collagen-rich (Figure 8).

Case 9: Disorganized inflammatory process (anarchical): Here the mixed picture showed slight predominance of allergic processes over the inflammatory one. Plasmocytes were more abundant among cell population (Figure 9).

Case 10: Disorganized inflammatory process (anarchical): There was great cell diversity in this case, with lamina propria rich in macrophages and fibroblasts. We could see non-definition of intercellular substance.

Case 11: Chronic inflammatory process (late response): There was tendency to organization and fibrosis in this case, but with present cell activity. We could see large quantities of collagen in the interstitium, which presented many areas of cell debris. Cell destruction was massive, with presence of cell anarchical distribution. We observed great cell diversity and presence of activated plasmocytes, slight tendency to mononuclear cell predominance.

Case 12: Non-acute non-chronic inflammatory process. Inflammatory response in this case was aggressive, with presence of macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasmocytes, presenting no predominance of one over the other. The interstitium presented cell debris. We detected areas with collagen deposition moving towards organization and resolution of the inflammatory process (late aspect, chronic).

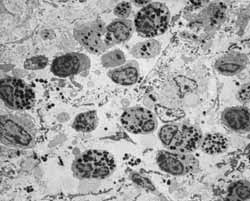

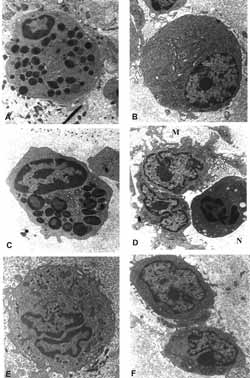

Case 13: Disorganized inflammatory process (anarchical). We observed disorganization of inflammatory process with presence of great cell element diversity. We did not find any inflammatory cell predominating over the others. We detected a mixed picture, in which inflammatory response predominated slightly over the allergic response (Figure 10).

DISCUSSION

Many factors are related to pathophysiology of CR. Much has been said about epithelial affections and mucociliary clearance in CR, but little has been studied about lamina propria of sinusal mucosa affected by chronic inflammatory processes. The cases that served as control group presented thin lamina propria, as described in the literature, completely different from patients in which we observed five types of inflammatory responses. Acute inflammatory process: 1 case; non-acute non-chronic inflammatory process - 5 cases; chronic inflammatory process - 2 cases; disorganized inflammatory process - 4 cases; indeterminate inflammatory process - 1 case. The most frequent types of response, the non-acute non-chronic inflammatory type and disorganized inflammatory process, despite being classified separately, presented similarities: great diversity of cell elements, without predominance of any cell series. In most of the situations, we observed associated elements of acute and chronic phase. In non-acute non-chronic process normally there is discrepancy between interstitial and cellular responses (acute or chronic) of inflammation. In the disorganized process, in addition to diversity of acute and chronic elements, we also saw an unexpected combination between representatives of allergic and non-allergic inflammatory responses.

In cases in which we can see a non-acute non-chronic inflammatory process, there is tendency to chronicity and resolution of inflammatory picture. In cases classified as disorganized inflammatory process, there is major non-definition of picture.

The two cases that show chronic inflammatory process presented evident signals of resolution of the picture. The inflammatory response apparently evolved within the expected levels, based on the sequence of events of the inflammatory process. They also showed cell abundance (chronic picture cellularity, tendency to mononuclear predominance), but the process was organized and we could see fibrosis in two cases.

We classified one of the cases as acute inflammatory process owing to neutrophilic predominance of cell infiltrate. The cells are normally associated with acute inflammation 1, 4. Many authors talk about types of histology alterations in CR and predominance of neutrophils can fall within one of these types.

The case judged to be indeterminate inflammatory process was hard to classify, since even in this patient we could observe different histology pictures side by side, without predominance of one over the other 5.

There were no glands on the lamina propria in any of the cases, probably owing to the fact that the location of the biopsy was the maxillary sinus (superior-lateral wall of the region is normally deprived of glands), which in this sinus tend to be found only around its natural ostium 6, 7.

Emphasizing cellularity of lamina propria of the maxillary sinus in the cases of CR, we can say that our evident findings of great diversity of cell elements agree with that of the world literature. In general, we hear about predominance of mononuclear leukocytes, but there is always the presence of polymorphonuclear granulocytes. Tos & Mogensen, (1984)8 studied the histology of 47 samples of maxillary sinus of 38 patients with CR and found in all cases different grades of infiltrate variations by leukocytes and plasmocytes. In few patients great leukocytarian infiltration was the predominant finding of lamina propria, whereas others presented eosinophil infiltration. Comparing this study with our data, we detected leukocytarian infiltration as the main histopathological finding of lamina propria in many of the patients. This cell infiltration, in 7 of our 13 cases (53.84%), showed great cell diversity, with varied grades of infiltration by lymphocytes and plasmocytes (as well as the patients by Tos & Mogensen). A predominantly eosinophilic infiltrate was seen in only one of our cases (7.69%).

A great increase in number of inflammatory cells of the lamina propria was detected in all patients studied by Stierna & Carlsöö5 (1990). The cells were mainly lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and occasionally polymorphonuclear granulocytes, which indicates the chronic nature of inflammatory response. Our data agree in part to findings of precious studies. We also detected great cell infiltration, but we did not managed to distinguish predominant cells in most of them (53.84%). Plasmocytes and polymorphonuclear cells were predominant, each one in one of our cases, which are the same cells as those reported by the authors referred above.

In this study, we defined direct relation between intensity of cell infiltration and intensity of lamina propria edema. Subepithelial thickness (interpreted as basal membrane hyalinization) is frequently associated with increase in number of eosinophils. In our case, we did not detect this association.

In the study by Forsgreen et al. 6 (1993) we found lymphocytes and monocytes as the predominant inflammatory cells in the infiltrate, even though polymorphonuclear granulocytes (such as neutrophils and eosinophils) have also been detected. We also found polymorphonuclears, but we did not reproduce the findings of mononuclear predominance, seen in only two cases (15.38%). Similarly to Stierna & Carlsöö5 (1990), they detected mucosa thickness (subepithelial) was closely related with quantity of inflammatory cells.

Demoly et al. (1998)9 found sinusal mucosa infiltrated with eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. There was no difference between these two groups, analyzing the infiltration by activated eosinophils and macrophages, but they observed increase in number of lymphocytes T and intraepithelial mast cells in the group of atopical subjects. Based on the study above referred, we can say that allergy is not responsible for eosinophilia of cell infiltrate in CR in all situations, which can justify the incompatible findings of presence of inflammatory and allergic elements together, such as in some of our cases classified as disorganized inflammatory process.

Ghaffar et al. (1998)10 stated that previous studies had demonstrated two different mechanisms involved in tissue eosinophilia in CR. In sinusal mucosa of patients with atopia, the increase in RNAm to Il-4 and IL-5 was potentially involved with increase of eosinophils in the tissue. The high expression of RNAm to Gm-CSF and IL-3 was correlated with density of tissue eosinophils in patients with allergic and non-allergic CR. Lee et al. (1998)11, in their study, also stated that there were different mechanisms for eosinophils in allergic and non-allergic patients.

Summing up, we detected a very wide diversity of cell elements in all cases, without predominance of any type of inflammatory process cell over another in 7 out of 13 cases, or 53.85%. In two cases (15.39%) there was mononuclear predominance; in one case, neutrophilic predominance (7.69%); in one case, eosinophilic predominance (7.69%), in one case plasmocyte predominance (7.69%), and in the last case, macrophage predominance (7.69%).

The organization of the interstitium and the presence or not of fibrosis in maxillary sinus lamina propria of patients with CR shows that inflammation tends to move towards process resolution.

The population of monocytes and macrophages is essential in repairing the normal tissue and the remaining cells of the wound site for some days and even weeks. In chronically inflamed sinusal mucosa, the continuous activation of monocular cells promotes proliferation of fibroblasts and development of fibrosis. By action of secreted cytokines, monocytes and macrophages participate in the debridment of microbiocidal processes and coordination of events involved in tissue repair 12.

In the study by Ghaffar et al.(1998) 10, already referred by us, the authors appointed the mast cells and eosinophils as the main producers of IL-6. Both epithelial and subepithelial expression of IL-6 in this study was greater in patients with CR associated with NP than in the control group. There was no difference between allergic and non-allergic patients, since production of IL-6 by mast cells is independent from the granulation phenomenon. The production of IL-6 is induced by IL-3, GMN-CSF and bacterial polysaccharides. This cytokine is appointed as an inductor of fibroblast proliferation, deposition of collagen and reduction of collagen rupture. All these actions contribute to the formation of fibrosis.

In our study, even though the number of cases did not allow a definite conclusion, we detected that fibrosis was more frequently found in cases with higher organization of interstitium and tendency to process resolution.

In cases classified as disorganized inflammatory process, we did not notice fibrosis in any of the patients, nor signals of process resolution. Maybe those are the cases in which we cannot progress to cure, regardless of appropriate treatment. To reach such a conclusion, we have to carry on with further studies, conducting postoperative histology follow-up. In cases classified as chronic inflammatory process, fibrosis was present in two studied patients, in association with mononuclear predominant infiltrate, showing a clear tendency to organization of interstitium and resolution of inflammatory process.

Out of five cases classified as non-acute and non-chronic inflammatory processes, three biopsies showed presence of fibrosis of maxillary sinus lamina propria. These cases have already shown some tendency to resolution of the picture, even though there was no definition of cellularity of the inflammatory process. In patients with predominance of neutrophilic cellularity, we observed mild fibrosis, which is in accordance with scarcity of monocytes, macrophages and eosinophils.

In some of our cases, especially cases 1 and 8, we detected fibrosis located in the lamina propria area, close to the epithelium, on the basal membrane region. According to Forsgren et al. (1996)12, thickness of basal membrane reflects an increase in deposition of collagen below the normal basal membrane and it is common in pathological situations in which epithelial cells are supported by the membrane, presenting accelerated processes of exfoliation and cell renovation. This thickness is frequently seen in asthmatic and /or atopic patients, which is in accordance with the observation by Stierna & Carlsöö, (1990)5 that subepithelial thickness is a finding more associated with increase in eosinophils, a cell related to allergic conditions. These authors interpreted this thickness as basal membrane hyalinization. It is important to point out that in our cases 1 and 8, in which we could see subepithelial fibrosis, there was no eosinophilic predominance.

Tissue affections observed in CR are consistent with biological activity of chemical mediators derived from inflammatory cells. Maybe this is the key to understanding disorganization of inflammatory process in some patients with CR, which could explain the difficulty to definitely cure the condition, even with the appropriate therapy (including surgical treatment). The regulation of the organization of inflammatory process events is essential for its resolution, be it by normal tissue repair or healing process. We analyzed the studied cases and observed that in most of the patients (9 out of 13 - 69.23%) there was disorganization of inflammatory picture.

Some authors call attention to the concept of differentiation of the microenvironment in nasal airway inflammation 13, 14. These studies can and should be correlated with studies of the chronically inflamed sinusal mucosa. The mechanism of regulation of inflammatory processes both in rhinosinusal mucosa with chronic inflammation and in nasal polyps should be similar, since these pathologies are very frequently associated. Many authors place chronic inflammation of nasosinusal mucosa as the main factor associated with formation of polypoid lesions 14, 15, 16. There is evidence that this hypothesis of microenvironment of inflammation in the airways is under some type of genetic and systematic control, or at the level of nasal airway. Since cytokines are intimately related to regulation of inflammatory process, they are probably submitted to genetic regulation, interfering with the progression of nasosinusal inflammatory process.

The study of inflammatory process of lamina propria of sinuses affected by chronic inflammation, in our opinion, should serve as a guideline correlating the aspects of inflammatory signals with levels of cytokine expression and picture progression, both histological and molecularly, after treatment. Based on it, we can improve our understanding of the evolution of the whole process, and maybe allow intervention at different steps to resolve the condition.

CONCLUSIONS

1) Maxillary sinus lamina propria in the studied patients was filled with increased infiltration of inflammatory cells, without specific predominance of one cell element over the others. We did not observe glandular elements on the maxillary sinus lamina propria, and fibrosis was detected in nearly half of the cases, of mild to moderate intensity, some times preferentially located right below the epithelium;

2) Most of the cases showed disorganization of the inflammatory process on maxillary sinus lamina propria. In the studied conditions, the inflammatory process did not follow normal evolution steps, rarely taking to complete resolution of the condition.

Figure 1: A- Chronic inflammatory process with predominance of mononuclear cells (2000X). B- Chronic inflammatory process with presence of fibrosis in the interstitium (2000X).

Figure 2: A- Lamina propria with marked fibrosis and few elements of inflammatory cell infiltrate (2000X). B- Lamina propria with marked inflammatory cell infiltrate (2000X).

Figure 3: Inflammatory infiltration without specific cell predominance in the lamina propria (2000X).

Figure 4: Acute inflammatory process with neutrophilic predominance on the lamina propria (2000X).

Figure 5: Lamina propria with large population of eosinophils (2000X).

Figure 6: Abundant inflammatory infiltrate on the lamina propria, with great cell diversity (3200X).

Figure 7: Lamina propria infiltrated with different inflammatory cells (3200x).

Figure 8: A- Area of subepithelial fibrosis (2000X). B- Marked and diversified inflammatory infiltrate on the lamina propria (2500X).

Figure 9: Atypical respiratory epithelium. A- LM: lamina propria with rich cellularity and predominance of plasmocytes (63X); B- TEM: the same lamina showing rich cellularity (2,000X); C- TEM: plasmocytes in larger magnification - arrows (3,200X).

Figure 10: TEM: diversified cell population found on the lamina propria of patients. A- eosinophil; (6,300X) B- plasmocyte; (6300X). C- mast cell; (10,000X) D- macrophage and neutrophil (6,300X) (M and N); E- macrophage; (10,000X) F- lymphocyte (6,300X).

REFERENCES

1. PEREIRA, F.E.L.; BOGLIOLO,L. Inflamações. In: BRASILEIRO FILHO, G., ed. Patologia geral. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara, 1993. Cap. 7, p. 111-143.

2. BAMBIRRA, E.A.; PAULINO, UU.H.M.; TAFURI, W.L.; PEREIRA, F.E.L.; BOGLIOLO,L. PEREIRA, F.E.L. Noções de imunopatologia. In: BRASILEIRO FILHO,G., ed. Patologia geral. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara, 1993. Cap. 9, p. 186-208.

3. PEREIRA, F.E.L. Etiopatogênese geral das doenças. In: BRASILEIRO FILHO, G., ed. Patologia geral. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara, 1993. Cap. 3, p. 19-44.

4. RUDACK, C.; STOLL, W.; BACHERT, C. Cytokines in nasal polyposis, acute and chronic sinusitis. American Journal of Rhinology, v. 12, n. 6, p. 383-8, 1998.

5. STIERNA, P.; CARLSÖÖ, B. Histopathological observations in chronic maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol, Stockholm, v. 110, p. 450-8, 1990.

6. FORSGREN, K.; STIERNA, P.; KUMLIEN, J.; CARSÖÖ, B. Regeneration of maxillary sinus mucosa following surgical removal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v. 102, p. 459-66, 1993.

7. EDELSTEIN, D.R.; BUSHKIN, S.C. Applied nasal physiology. In: ANAND, V. K.; PANJE, W.R. eds. Practical endoscopic sinus surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 18-9, 1993.

8. TOS, M.; MOGENSEN, C. Mucus production in chronic maxillary sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol, Stockholm, v. 97, p. 151-9, 1984.

9. DEMOLY, P.; CRAMPETTE, L.; LEBEL, B.; CAMPBELL, A.M.; MONDAIN, M.; BOUSQUET, J. Expression of cyclo-oxygenases 1 and 2 proteins in upper respiratory mucosa. Clinical and Experimental Allergy, v. 28, p. 278-83, 1998.

10. GHAFFAR, O.; LAVIGNE, F.; KAMIL, A.; RENZI, P.; HAMID, Q. Interleukin-6 expression in chronic sinusitis: Colocalization of gene transcripts to eosinophils, macrophages, T lymphocytes, and mast cells. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, v. 118, n. 4, p. 504-11, 1998.

11. LEE, C.H.; RHEE, C-S.; MIN, Y-G. Cytokine gene expression in nasal polyps. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v. 107, p. 665-70, 1998.

12. FORSGREN, K.; FUKAMI, M.; PENTTILÄ, M.; KUMLIEN, J.; STIERNA, P. Endoscopic and Caldwell-Luc approaches in chronic maxillary sinusitis: A comparative histopathologic study on preoperative and postoperative mucosal morphology. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v. 104, p. 350-7, 1996.

13. ALLEN, J.S.; EISMA, R.; LA FRENIERE, D.; LEONARD, G.; KREUTZER, D. Characterization of the eosinophil chemokine rantes in nasal polyps. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v. 107, p. 416-20, 1998.

14. BERNSTEIN, J.M.; GORFIEN, J.; NOBLE, B. Role of allergy in nasal polyposis: A review. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, v. 113, p. 724-32, 1995.

15. DAVIDSSON, A.; DANIELSEN, A.; VIALE, G.; OLOFSSON, J.; DELL'ORTO, P.; PELLEGRINI, C.; KARLSSON, M.G.; HELLQUIST, H.B. Positive identification In Situ of mRNA expression of IL-6, and IL-12, and the chemotactic cytokine RANTES in patients with chronic sinusitis and polypoid disease. Acta Otolaryngol, Stockholm, v. 116, p. 604-10, 1996.

16. PARK, H-S.; KIM, H-Y.; NAHM, D-H.; PARK, K.; SUH, K-S.; YIM, H-E. The presence of atopy does not determine the type of cellular infiltrate in nasal polyps. Allergy and Asthma Proc, v. 19, p. 373-7, 1998.

*Master studies under course, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, FMRP-USP.

**Technician in the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy, Cellular and Molecular Biology and Pathogenic Bioagents.

***Ph.D., Professor, Department of Surgery and Anatomy, FMRP-USP.

****Associated Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, FMRP-USP.

Study presented at II Congresso Triológico de Otorrinolaringologia da SBORL, Goiania-2001.

Address correspondence to:

Prof Dra. Wilma T. Anselmo-Lima - Departamento de Oftalmologia, Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço do HCFMRP-USP, Avenida Bandeirantes n.º 3900 - CEP: 14049-900 Ribeirão Preto - SP -Tel (0xx16) 602-2862- fax: (0xx16) 602-2860.