Year: 2000 Vol. 66 Ed. 5 - (12º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 500 to 504

Vocal Fold Paralysis in Children.

Author(s):

Claudia A. Eckley*,

André C. Duprat**,

Maria F. P. Carvalho***,

Branca Liquidato***,

André F. Moreira****,

Henrique O. Costa*****.

Keywords: vocal fold paralysis, dysphonia, childhood

Abstract:

Introduction: Vocal fold (VF) paralysis in childhood presents in a distinctly from that of adults mostly because of the smaller size of the infantile larynx, but also because the causes are frequently related to congenital abnormalities or birth traumas. It is the second most common cause of stridor in childhood, thus it must be diagnosed and treated early and adequately to secure the airway and feeding. Objectives: Report the authors' experience in the diagnosis and treatment of children with uni or bilateral vocal fold paralysis comparing the difficulties encoutered to those reported in literature. Material and methods: Seventeen children (seven boys and 10 girls) were diagnosed and treated for VF paralysis from July,1994 to February, 2000. Diagnosis was made based on history and fibreoptic examination of the larynx and upper airways. Results: Eight patients presented unilateral VF paralysis and nine had bilateral paralysis. Paralysis was mostly secondary to surgical correction of congenital heart deformities (40%) followed closely by congenital or acquired central nervous system abnormalities (30%). The majority of children were treated conservatively. Three of the four patients who eventually were submitted to laryngeal surgery were only operated after a 1-year follow-up period. Four cases resolved spontaneously after a mean 15-month follow-up period. The average follow-up period was 3,1 years. Discussion and conclusions: Flexible endoscopy has made possible a non-invasive diagnosis and follow-up of laryngeal VF paralysis in children. Whenever possible conservative or reversible treatment should be augmented in order to allow spontaneous recovery of the vocal fold paralysis.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The study of pediatric population with laryngeal alterations is object of great interest and importance, not only because the mechanisms that cause abnormalities differ, but also clinical and therapeutic approaches are diverse.

Vocal fold paralysis in childhood was described for the first time by Taylor, in 1882. Between 30's and 60's, some isolate studies of vocal fold paralysis in childhood were reported4,11,12,19,28; however, only after 1975 reports became more frequent, probably due to a larger number of diagnosed cases after the development of flexible optical fibers, which enabled the performance of non-invasive exams in children and even newborns. The other potential cause for increased number of laryngeal paralysis diagnosis was the increasing incidence of low weight birth and multiple malformed newborns that did not use to survive in the past.

Vocal fold paralysis is the second most frequent cause of stridor in newborns - laryngomalacea is the first one1,3,27. In spite of being uncommon in newborns and infants, it may result in high morbidity if present. If bilateral, the extension is even more severe and may generate respiratory failure (when in adduction) or aspiration presentations (when in abduction). Unilateral cases may be present with dysphonia or weak cry, but similarly to the adult population, children seem to be oligosymptomatic9,10,14,30. However, even an event of unilateral paralysis may lead to respiratory failure in newborns or infants; that is why early precise diagnosis is so important.

Differently from the causes of vocal fold paralysis in adults, normally due to surgical traumas, tumors or neurological dysfunction, paralysis in children have completely different causes, divided into congenital and acquired uni or bilateral causes.

The most common congenital causes are malformations of central nervous system. The congenital malformation most mentioned in the literature is Arnold-Chiari malformation, frequently associated with meningoencephalocelus and hydrocephalus11,25. Cardiovascular diseases and malformations are the second most common causes of vocal fold paralysis in childhood5,8,15,25. Cardiomegalia secondary to interseptal defect or Fallot tretalogy may elongate left recurrent laryngeal nerve. Large vessels anomalies, such as the case of dilated carotid artery, persistence of ductus arteriosus or vascular ring, may also result in laryngeal paralysis7,24.

Generally speaking, neurological disorders are more associated with bilateral paralysis, whereas unilateral modalities are more related to birth or surgical traumas after correction of cardiac impairment22,29. Left recurrent laryngeal nerve is more vulnerable than the right one because its path is longer and goes around the aorta arch.

Acquired causes include infectious, toxic, metabolic, idiopathic and traumatic events. Toxic, infectious, or metabolic causes have been more rarely reported. CNS viral infections with Epstein-Barr20,26 or other virus are reported as isolate cases25. Meningitis, encephalitis and poliomyelitis are the most well-known causes of vocal fold paralysis8. Toxic reactions to anti-malaria drugs11, chemotherapic agents3,4,11, and organophosphate insecticides23 have been more rarely described as causes of vocal fold paralysis.

Traumatic causes, as mentioned above, may be a result of birth or surgical trauma, after repair of cardiac or esophageal malformations, among others. Cranial trauma during birth and hypoxia are well-known causes of laryngeal paralysis.

Idiopathic paralyses after viral infections are controversial, but they seem to disappear spontaneously after 2 to 6 months of follow-up and they rarely require tracheotomy to maintain the airways.

As the child approaches teenager years, incidence of vocal fold paralysis decreases and etiologies become closer to those of adult population.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The symptoms most commonly related to vocal fold paralysis in children are: stridor, cyanosis, apnea, difficulty to suck, leading to aspiration, intercostal retraction, dysphonia and other alterations of cry and speech.

Laryngeal stridor, cyanosis and apnea are more frequently related to children who have paralysis on both vocal folds. Dysphonia and cry and speech alterations are more common in unilateral paralysis. Difficulties in feeding and intercostal retraction are equally reported in uni and bilateral paralysis22.

In children, cry may not be altered and cause a high frequency stridor, not necessarily related to acute respiratory distress. These cases are normally followed by suprasternal and epigastric retraction. When there is prolonged obstruction, fatigue may take to respiratory failure, requiring orotracheal intubation or tracheotomy.

The degree of aspiration, especially of liquids, helps to locate the lesion as above or below the origin of superior laryngeal nerve. However, with time, most of the patients who have superior laryngeal nerve impairment find adaptation mechanisms to control aspiration episodes, and then this criterion is not valid anymore.

Respiratory obstruction is obviously the most severe symptom, revealed by stridor, cyanosis, dyspnea, retraction and movement of nasal ala. The existence of reduced laryngeal dimensions in childhood, associated with a flaccid immature organ, results in risk of edema and significant respiratory obstruction in any episode of upper airway infection. In fact, in cases in which paralysis is unilateral, or in bilateral cases with large glottic chink, initial symptoms may be present only after an episode of acute upper airway infection.

The objective of the present study was to report the experience of our service in diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal paralysis in children.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

In the period between July 1994 and February 2000, 17 pediatric patients were diagnosed and treated with vocal fold paralysis in our service. The mean age of the group was 8.4 years, ranging from 2 weeks to 14 years. Ten patients were girls and 7 were boys. Nine patients had bilateral paralysis and 8 had unilateral paralysis.

All patients were diagnosed through nasofibrolaryngoscopic exam, conducted under topic ambulatorial anesthesia. It enabled assessment of laryngeal mobility and sensitivity.

Patients were followed up for an average period of 3.1 years, ranging from 1 month to 6 years.

RESULTS

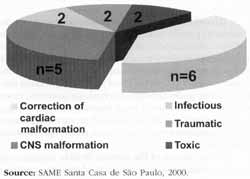

The most common cause of paralysis was surgical repair of congenital or acquired cardiac malformation (40%), followed by CNS alteration (30%). Figure 1 shows distribution of patients according to etiology of paralysis. There was no statistically significant difference in etiologies of the paralysis between the group of patients younger than 4 years (8 patients) and those older than 4 (9 patients).

The most common symptoms of presentation in infant population (younger than 1 year) was laryngeal stridor and cyanosis. In older children, the most common symptom was dysphonia, especially in case of unilateral paralysis. For most children, symptoms were reported immediately after the event (surgical, infectious or traumatic) that caused the paralysis.

Out of 8 patients who had unilateral vocal fold paralysis, 5 had it paralyzed on median or paramedian position, responding well to speech therapy. Three patients with unilateral paralysis in abduction did not produce significant improvement in vocal quality after an average period of 1 to 5 months of speech therapy. Two of these patients were submitted to thyroplasty and had improvement of vocal quality, without impairment of respiratory pattern. The other patient had severe cardiopathy and all surgical procedures were contraindicated, even under topic anesthesia.

Only two out of 9 patients with bilateral vocal fold paralysis were submitted to laryngeal surgery. One patient who was 12 years old had adducted bilateral vocal fold paralysis caused by acute intoxication by organophosphate insecticides. The patient was initially submitted to emergency tracheostomy and was later conservatively followed-up for 13 months. In this period, decannulation was not possible and he was finally submitted to left cordectomy and arytenoidectomy to enable decannulation. The other patient, who had adduction bilateral paralysis, was diagnosed at 2 months of age when he came to the Emergency Room with respiratory failure. The patient was submitted to primary bilateral cordectomy, and managed to stabilize the respiratory symptoms. The other 3 patients with bilateral vocal fold paralysis were also tracheostomized, all of them temporarily (6 months to 1 year), during the acute phase after the onset of paralysis. Two of these patients improved spontaneously, enabling decannulation; the third one was submitted to tracheoplasty to correct subglottic stenosis (caused by prolonged orotracheal intubation), and after it the patient was also decannulated.

Figure 1: Etiologies of laryngeal paralysis.

Partial or total spontaneous regression of paralysis occurred in 4 cases. Three of them,, mentioned above, had bilateral vocal fold paralysis. One of them remained with left vocal fold paresis and normalized right vocal fold after 16 months. The others improved mobility of both vocal folds, achieving phonatory and respiratory compensation with speech therapy. The fourth case was of unilateral (right) paralysis.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Every newborn, infant or child who have symptoms of cyanosis, stridor, aspiration or weak cry, any esophageal, heart or CNS anomaly, should be considered as risk population for vocal fold paralysis, and should be properly assessed. However, assessment of such younger children is a challenge, because even when using flexible nasofibroscope, it is very difficult to see the paralysis, especially if unilateral. Nevertheless, nasofibrolaryngoscopy is still the preferred diagnostic exam for these cases.

If possible, we should try to palpate arytenoid, in order to assess its passive mobility, since congenital or traumatic fixation of cricoarytenoid joint, posterior laryngeal membranes and congenital fusion of vocal folds may only be differentiated from paralysis through this maneuver30. This is the reason why so many authors still prefer direct laryngoscopy using rigid laryngoscope under anesthesia to evaluate suspected cases. We should be very careful when inserting the rigid laryngoscope, because it may fix the vocal fold, giving the impression that it is a paralysis when in face there is no laryngeal mobility impairment.

In the opinion of the authors, flexible laryngoscope provides enough visualization of vocal fold mobility, and it has the advantage of being performed when the child is awaken, in more physiological conditions. It is especially important in children who are severely sick and to whom a general anesthesia would pose a major risk to their general health.

The main limitation in the use of flexible laryngoscopy in children is lack of collaboration from the patient. It forces the exam to be shortened and hinders visualization of larynx. In addition, it is not possible to perform passive mobilization of laryngeal structures when using this technique.

Swallowgrams may assist in determining associated pharyngoesophageal alterations, or gastroesophageal reflux, revealing the diagnosis of several congenital vascular malformations6. Laryngeal CT scans are less specific and the characteristic signs of vocal fold paralysis are anterior position of arytenoid on affected side, ipsilateral dilation of pirifom sinus and bowing of thyroid cartilage, associated with dilation of ventricle on the same side. CT scan of central nervous system is indicated to exclude malformations and other neurological abnormalities.

Electromyography of cricothyroid and thyroarytenoid muscles is the gold standard for diagnosis of laryngeal mobility in adults, providing information to differentiate paralysis and paresis from other laryngeal structural alterations, as well as about prognosis. However, its use is very limited in children, because it depends on general anesthesia. The reports of the use of this diagnostic technique in children are very scarce and there is not normal range standardization for children18. In our sample, two patients were submitted to laryngeal electromyography. They were both pre-teenagers and collaborated with the exam, which was important for case intervention, since we obtained data about the degree of denervation of laryngeal muscles.

Treatment of laryngeal paralysis is influenced by several factors, including type of paralysis (uni or bilateral), degree of respiratory obstruction and aspiration, and also by the cause of paralysis. Other factors to be considered are association with other neurological deficits (swallowing and breathing), likelihood of spontaneous recovery, life expectancy and patient's mental potential, among others. Etiological diagnosis was defined in 92% of our cases.

Treatment priorities are to maintain good airway status and appropriate nutrition. Tracheotomy is necessary in 50% to 80% of the children with bilateral vocal fold paralysis, and in only 20% of the children with unilateral paralysis2,6,16,17,21,25. In our sample, 13% were tracheostomized (all had bilateral paralysis), and they remained with the cannula for an average period of 6.8 months. Nasogastric tubes and gastrotomies may be temporarily necessary in cases of bilateral paralysis, until the child acquires appropriate swallowing techniques. Aspiration is less present in cases of unilateral paralysis. Minimal degrees of aspiration may be noticed, despite their asymptomatic nature.

Spontaneous recovery of paralysis may take place in average between 6 months to 1 year after its onset25, and then are reports of cases that recovered after 3 years. There is mom likelihood of recovery in cases of intoxication, infection, or it cases of stretching or compression of laryngeal nerves, without direct section or lesion. Therefore, invasive and irreversibly treatments should be postponed to give time to spontaneous recovery. Four of our patients had improvement or total recovery of laryngeal paralysis within 18 months.

It is difficult to define the right time to intervene it children with laryngeal paralysis; however, once breathing and nutrition are guaranteed, other corrective measures may be postponed for at least 1 year after onset of paralysis.

REFERENCES

1. BERKOWITZ, R. G.-Laryngeal Electromyography Finding in Idiopathic Congenital Bilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis. Ann. Otol Rhinol. Laryngol., 105: 207-212, 1996.

2. BIGENZAHN, W.; HOEFLER, H. - Minimally Invasive Laser Surgery for the Treatment of Bilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis Laryngoscope, 106:791-793, 1996.

3. BOEY, H. P.; CUNNINGHAM, M. J.; WEBER, A. L. - Central Nervous System Imaging in the Evaluation of Children with True Vocal Cord Paralysis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 104: 76-77 1995.

4. CAVANAGH, F. -Vocal Palsies in Children. J. Laryngol. Otol. 69: 399-418, 1955.

Cohen, S. R.; Geller, K. A.; Buns, J. W.; Thompson, J. W. - Laryngeal Paralysis in Children. A Long-term Retrospective Study. Ann Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 91: 417-424, 1982.

5. DEDO, D. D. - Pediatric Vocal Cord Paralysis. Laryngoscope, 89: 1378-1384, 1979.

6. FAN, L. L.; CAMPBELL, D. N.; CLARKE, D. R.; WASHINGTON R. L.; FIX, E. J.; WHITE, C. W. - Paralyzed Left Vocal Cord Associated with Ligation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus. J. Thorac. Surg., 98: 611-613, 1989.

7. FRIEDMAN, E. M. - Role of Ultrasound in the Assessment of Vocal Cord Function in Infants and Children. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 106.- 199-209, 1997.

8. GAUDEMAR, I.; ROUDAIRE, M.; FRANCOIS, M.; NARCY, P.Outcome of Laryngeal Paralysis in Neonates: A Long Term Retrospective Study of 113 Cases. Int. J Ped. Otorhinolaryngol., 34:101-110, 1996.

9. GENTILE, R. D.; MILLER, R. H.; WOODSON, G. E. - Vocal Cord Paralysis in Children 1 Year of Age and Younger. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 95:622-625, 1986.

10: GENTILE, R. D.; MILLER, R. H.; WOODSON, G. E. -Vocal Cord Paralysis in Children 1 Year of Age and Younger. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 95.- 622-625, 1986.

11. GRAHAM, M. D. - Bilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis Associated with Meningomyelocele and the Arnold-Chiari Malformation. Laryngoscope, 73: 85-92, 1963.

12. HEATLY, C. A. -The Larynx in Infancy. A Study of Chronic Stridor. Arch. Otolaryngol., 29: 90-103, 1939.

13. HIRANO, M.; TANAKA, S.; TANAKA, Y.; HIBI, S. Trancutaneous Intrafold Injection for Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis: Functional Results. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 99: 598-604, 1990.

14. HOLINGER, L. D.; HOLINGER, P. C.; HOLINGER, P. H. Etiology of Bilateral Abductor Vocal Cord Paralysis. A Review of 389 Cases. Ann. Otol., 85:428-436, 1976.

15. KOPPEL, R.; FRIEDMAN, S.; FALLET, S.-Congenital Vocal Cord Paralysis with Possible Autossomal Recessive Inheritance: Case Report and Review of Literature. Am. J. Med. Gen., 64: 485-487, 1996.

16. LEVINE, B. A.; JACOBS, I. N.; WETMORE, R. F.; HANDLER, S. D. - Vocal Cord Injection in Children with Unilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis. Arch. Otolaryngol., H & N Surg., 121: 116-119, 1995.

17. LEVY, R. B. - Experience with Vocal Cord Injection. Ann Otol 85: 440-450,1976.

18. Liquidato, BM; Eckley, C. A.; Alves, A. L.; Rossi, H.; Bezerra, H. Paralisia de Pregas Vocais em Crianças e Adolescentes. Em: Laringologia a Voz Hoje. Behlau, M. Revinter, RJ, pgs. 293-296, 1997.

19. NEW, G. B.; CHILDREY. J. H. -Paralysis of the Vocal Cords. A Study of Two-Hundred and Seventeen Medical Cases. Arch. Otolaryngol., 16 (2): 143-159, 1932.

20. PARANO, E.; PAVONE, L.; MUSUMECI, S.; GIAMBUSSO, F.; TRIFILETTI, R. R. - Acute Palsy of the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Complicating Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Neuro pediatrics, 27. 164-166, 1996.

21. REMACLE, M.; LAWSON, G.; MAYNÉ, A.; JAMART, J. -Subtotal Carbon Dioxide Laser Arytenoidectomy by Endoscopic Approach for Treatment of Bilateral Cord Immobility in Adduction. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 105: 438-445, 1996.

22. ROSIN, D. F.; HANDLER, S. D.; POTSIC, W. P.; WETMORE, R. F.; TOM, L. W. C. - Vocal Cord Paralysis in Children. Laryngoscope, 100: 1174- 1179, 1990.

23. SILVA, H. J.; SANMUGANATHAN, P. S.; SENANAYAKE, N. Isolated Bilateral Laryngeal Nerve Paralysis: A Delayed Complication of Organophosphorus Poisoning. Human & Experimental Toxicol, 13:171-173, 1994.

24. THOMPSON, J. W.; STOCKS, R. M. - Brief Bilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis after Insecticide Poisoning. Arch Otolaryngol, H&N Surg., 123: 93-96, 1997.

25. TUCKER, H. M. - Vocal Cord Paralysis in Small Children: Principles in Management. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 95: 618-621, 1986.

26. WOODMAN, D.; PENNINGTON, C. L. -Bilateral Abductor Paralysis: 30 Years Experience with Arytenoidectomy. Ann. Otol., 85: 437-439, 1976.

27. WOODSON, G. E.; MILLER, R. H. -The Timing of Surgical Intervention in Vocal Cord Paralysis. Otolaryngol, H&N Surg., 89: 264-267, 1981.

28. WORK, W. P. - Paralysis and Paresis of the Vocal Cords. A Statistical Review. Arch. Otolaryngol., 34: 267-282, 1941.

29. ZAPLETAL, A.; KURLAND, G.; BOAS, S. R.; NOYES, B. E.; GREALLY, P.; FARO, A.; ARMITAGE. J. M.; ORENSTEIN, D. M. - Airway Function Tests and Vocal Cord Paralysis in Lung Transplant Recipients. Ped. Pneumol., 23: 87-94, 1997.

30. ZBAR, R. I. S.; CHEN, A. H.; BEHRENDT, D. M.; BELL, E. F.; SMITH, R. J. H. - Incidence of Vocal Fold Paralysis in Infants Undergoing Ligation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus. Ann. Thorac. Surg., 61: 814-816, 1996.

* Assistant professor of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo/ SP.

** Professor and Instructor of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo/ SP.

*** Post-graduate studies under course at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo/ SP.

**** Resident of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo/ SP.

***** Joint Professor of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo/ SP.

Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo. Presented as free communication at I Congresso Triológico Brasileiro.

Address for correspondence: Dra. Claudia A. Eckley - Rua Sabará 566, cjt° 23 - Higienópolis - 01239-011 São Paulo/ SP - Tel/fax: (55 11) 257-2686.

Article submitted on May 24, 2000. Article accepted on July 13, 2000.