Year: 2000 Vol. 66 Ed. 4 - (7º)

Artigos Originais

Pages: 355 to 359

Perioperative Management of Sickle Cell Patients in Otolaryngologic Surgery.

Author(s): Marise P. C. Marques*.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, otolaryngologic surgery, sickling crises

Abstract:

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to standardize a medical and surgical perioperative protocol to management of homozygous sickle cell disease in otolaryngologic surgery. Material and Method: The judicious use of peroperative transfusion regimens to have S haemoglobin level fewer than 15% and a haemoglobin level greater than 10 mg/dL. The surgical procedures were under general anesthesia and hyperhydartation. The body temperature and oxygen saturation were monitorized, with avoidance of hypoxia, acidoses and cold. The operative technique for tonsillectomy was modified, and a total close of the tonsil's place was performed. Conclusion: Using this guidelines in five otolaryngologic cases, no complications was observed at the institution.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Sickle anemia is a form of hereditary hemolytic disease, predominant in black people and their descendents. It is due to a structural abnormality of b-globulin chain of adult (A) hemoglobin (Hb), resulting from the substitution of valine by glutamic acid formed by Hb S. Heterozygous state Hb AS is called sickle trace and homozygous Hb SS is called sickle anemia per se5,7,10.

The sickle phenomenon results from the aggregation of cells with Hb SS causing two types of phenomena: hemolysis and vasoconstrictive episodes, causing severe pain, renal failure, auto-splenectomy, hepatomegalia, cirrhosis, leg ulcers, pulmonary infarction, pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, cardiomegalia, chronic infections, priapism, bone marrow necrosis, hematuria, blindness and encephalic vascular accident (EVA). The phenomenon takes place preferably under conditions of hypoxia, dehydration, hypothermia, infection and acidosis. Normally, the higher the percentage of Hb SS erythrocytes, the more severe is sickle anemia2,5,10.

Auto-splenectomy predisposes the subject to infection by encapsulated bacteria, such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. Because of that, patients should be immunized against these germs. Since these microorganisms are very prevalent in upper airway infections, there is a high incidence of sinusitis, otitis and tonsillitis in this population. We should emphasize repetitive infections and chronic respiratory obstruction as aggravating factors of the progressive status of anemia5,10.

The purpose of this study was to raise the issue about the importance of otorhinolaryngologic surgical treatment in patients with sickle anemia. It is essential that the teams of hemotherapy, ENT and anesthesia work together in order to prevent complications. We proposed here a pre, peri and postoperative preparation of these patients.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

We conducted a prospective study of 5 homozygous patients for sickle anemia, divided into 4 female and 1 male patient, ages ranging from 8 to 18 years and mean age of 13,4 years. They had tonsil, adenoid and turbinate hypertrophy, determining obstruction and/or repetitive infections of upper airways.

All patients were submitted to routine preoperative exams, including CBC, coagulogram, percentage dosage of Hb SS, glicemia, seric urea dosage, exam of abnormal elements and sediments in urine and surgical risk directed by organic sequelae and anemia.

All patients had Hb SS index higher than 30%, with sickling crises. Owing to it, we maintained a scheme of hypertransfusion with personalized blood exchange, so that the percentage of Hb SS would not exceed 15, with Rh phenotyped blood and Kell antigens, screened for hemoderived-transmissible diseases by the Service of Hemotherapy of Institute of Hematology in Rio de Janeiro. As a preoperative preparation, all patients were submitted to exchange transfusion, up to the maximum level of 15% Hb SS and total hemoglobin higher than 10mg/dL.

Perioperatively, the patients were maintained in hyperhydration, with oxygen saturation higher than 95%, heated with thermal blanket or mattress. The surgery was carried out with hemostasia control.

After conduction of adenoidectomy, we placed a temporary packing in the rhinopharynx. If there was nasal posterior bleeding after the removal of the packing, we left a posterior packing with gauze and zinc oxide ointment in oil vehicle - a bacteriological substance.

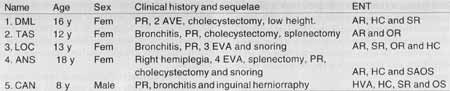

After the resection of each tonsil, their sites were completely closed with Vicryl 3-0. After the surgery in inferior turbinate - submucous cauterization or partial turbinectomy, nostrils were packed for 24 hours with synthetic foam, recovered by the middle finger of a latex surgical glove number 8, lubricated with zinc oxide ointment. Patients were maintained post6peratively with hyperhydration and we conducted a new CBC within the first 24 hours (Table 1).

RESULTS

All patients had history of upper airway obstruction and one patient had obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Four patients had repetitive tonsillitis and 3 had sinusitis and/or repetitive otitis. Three patients had already had EVA.

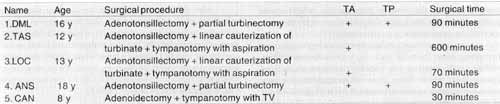

Four patients were submitted to adenotonsillectomy, two to partial inferior turbinectomy and two to linear cauterization of turbinate. Out of these, two undertook also tympanotomy with aspiration of both ears. The fifth patient was submitted to adenoidectomy with bilateral tympanotomy and placement of ventilation shunt on the inferior quadrant of tympanic membranes. The first four patients maintained anterior packing for 24 hours, and in two we also used posterior packing.

Surgical time varied from 30 to 90 minutes. There was no evidence of complications pre, peri or postoperatively related to the surgical act or the underlying disease. They were all discharged without anterior or posterior nasal packing 24 hours after the procedure (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Patients with sickle anemia manifest differently, from asymptomatic to severely compromised, with central nervous system (CNS) complications, severe hemolytic anemia and pain episodes. According to Adams et al., surgery in these patients is considered historically complicated, reaching perioperative complications rates of about 50%, normally associated with hypoxia, intravascular volume depletion, hypotension, hypothermia, infection and acidosis. Transfusion reactions, pain episodes, hemolytic crises, pulmonary embolism, fever related to atelectasia, urinary tract infection, thrombophlebitis and infection of surgical site, dehydration, jaundice, hepatitis, acute pulmonary syndrome and aloantibodies are the most common complications1,2,7,10.TABLE 1 - Summary of patients sample.

Key: Age in years, PR - repetitive pneumonia, SAOS - sleep obstructive apnea syndrome, HVA - adenoid hypertrophy, I AR - repetitive tonsillitis, HC - turbinate hypertrophy, SR - repetitive sinusitis, OR/OS - repetitive otitis / serous otitis.

TABLE 2 - Results.

Key: Age in years, TA - anterior packing, TP - posterior packing, TV - ventilation tube.

Monitoring of blood pressure and oxygen saturation is extremely important, and the concentration of oxygen of the inspired fraction should be kept at about 0.6 and, if needed, additional volumes of oxygen should be administered. When po2 falls to 80 mmHg, viscosity of Hb SS blood increases drastically2,7,10.

It is also important to prevent acidosis through alkalization with bicarbonate and/or hyperventilation, because an alkali mean deviates the oxygen dissociation curve to the left, avoiding deoxygenation of hemoglobin. Although they have not been used in our patients, they are good methods to prevent sickling episodes.

The use of perioperative heating, with thermal blanket or mattress and infusion of solutions at about 36.5° C also helps with prophylaxis. These resources were used with our patients in order to avoid hypothermia2,10.

An excellent measure is liquid hyperinfusion, calculated approximately 1.5 times more than needed, started about 12 hours preoperatively axed maintained peri and postoperatively for at least 24 hours. It is effective because hyperhydration reduces blood viscosity arid avoids microvascular agglutination. We conducted prophylactic antibiotic therapy with venous Cephatine one hour before and maintained it for 24 hours postoperatively to control bacteremia and avoid leukocytosis, another predisposing factor to sickling episodes, as recommended by several authors2,7,10.

Correction of anemia and reduction of percentage of red cells with Hb S reduce intravascular sickling episodes. The regimen of preoperative transfusion to keep the total level of hemoglobin between 10 and 12 mg/dL is considered a conservative regimen, whereas there are more aggressive regimens, with exchange transfusion to reduce levels of Hb SS to less than 15%, still considered controversial. Vichinsky et al., in 1995, showed that there was not an increase in perioperative complications with conservative treatment and that more aggressive treatments could lead to formation of aloantibodies and virus contamination, such as hepatitis and acquired human immunodeficiency (HIV). Koshy, et al., in 1995, showed that there is no association between preoperative levels of Hb A and complications, but that total levels of hemoglobin lower than 9.2 mg/ dL were related to complications. Adams et al. and Waldron et al. in 1999, did not recommend aggressive treatment as a way of preventing complications. Waldron et al. in 1999 came to similar conclusions in patients submitted to otorhinolaryngologic surgeries1,2,6,7,8,11.

It is known that patients with high level of fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) - 20 to 30% against the normal level of 2%, normally have a clinical course that is more benign, probably because there would be a dilution of Hb SS inhibiting polymerization. Many authors believe that careful preoperative care and perioperative care provided by the surgical team and the anesthesiologist are more important than any kind of transfusion therapy1,2,6,7,8,11.

In our patients we adopted the regimen of hypertransfusion with blood exchange for levels of Hb SS lower than 15%, because all of them had already had severe complications of the underlying disease and were already submitted to regimen of hypertransfusion with routine monthly exchange. The regimen of hypertransfusion with exchange is indicated when there is acute priapism, acute pulmonary syndrome with hypoxia, retina apoplexy, EVA and before cardiopulmonary angiography is performed. It is believed that transfusion with exchange reduces the risk of infections, because intakes away immunological components from the site of infection, removes bacteria and endotoxins, improving spleen function due to better microcirculation. In order to avoid contamination and formation of aloantibodies, transfusions are personalized, with Rh phenotyped blood and Kell antigens, and screened for hemoderived-transmissible diseases. Hypertransfusion without exchange suppresses the production of cells with Hb SS by the bone marrow, increases significantly blood viscosity, causes cardiac overload, iron overload and the blood in the bag may also trigger a crisis, because it is cold and acid, with high oxygen affinity-cells2,7.

An important complication that may be present postoperatively is acute pulmonary syndrome, responsible for more than 25% of deaths. The most common symptoms are fever, cough and thoracic pain, followed by tachydyspnea, stridor and hemoptisis. It is characterized by recent pulmonary infiltrate seen in thorax x-ray. The peak incidence of this affection is in children aged 2 to 4 years. It is more frequent in patients with genotype SS, low levels of Hb F and total hemoglobin. The microorganisms most frequently isolated in these cultures are S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. General anesthesia, leukocytosis, surgical time longer than 120 minutes, high risk surgeries and history of pulmonary disease are relevant factors. Since long surgical time is an aggravating and predisposing factor of acute pulmonary syndrome, this surgery should not be performed by prentices or inexperienced surgeons. None of our patients developed this syndrome3,4,9.

CONCLUSION

1. Patients with sickle anemia and surgical otorhinolaryngologic affections should be operated, provided that special preoperative care be taken.

2. It is paramount that ENT, anesthesia and hemotherapy teams work together in an integrated fashion.

3. Prophylaxis of hypoxia, hypothermia, dehydration, acidosis and infections are essential for prevention of hemolytic and/or vasoconstrictive crises.

4. Surgeries should be performed by experienced surgeons.

5. Levels of total Hb are more important that percentages of Hb SS in transfusion preoperative preparation.

6. Hypertransfusions should only be conducted to obtain levels of Hb SS lower than 15% in patients who already have a regimen of hypertransfusion with exchange, because of severe complications of sickle anemia.

7. Hypertransfusions should be personalized, with Rh phenotyped blood and Kell antigens, and screened for hemoderived-transmissible diseases.

REFERENCES

1. ADAMS, D. M.; WARE, R. E.; SCHULTZ, W. H.; ROSS, A. K.; OLDHAM, K. T.; KINNEY, T. R. - Successful surgical outcome in children with sickle hemoglobinopathies: the Duke University experience. J. Pediatr. Surg., 33: 428-32, 1998.

2. BISCHOFF, R. J.; WILLIAMSON III, A.; DALALI, M. J.; RICE, J. C.; KERSTEIN, M. D. - Assessment of the use of transfusion therapy perioperatively in patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Ann. Surg., 207(4), 434-8, 1988.

3. CHARACHE, S.; SCOTT, J. C.; CHARACHE, P. - "Acute chest syndrome" in adults with sickle anemia. Arch. Intern. Med., 139: 67-69, 1979.

4. DELATTE, S. J.; HEBRA, A.; TAGGE, E. P.; JACKSON, S.; JACQUES, K.; OTHERSEN, H. B. JR.- Acute chest syndrome in the postoperative sickle cell patient. J. Pediatr. Surg., 34: 18891, 1999.

5. FORGET, B. G. - In: Wyngaarden. J. B.; Smith, L. H. - Tratado de Medicina Interna, 16ª Edição, Rio de Janeiro, Ed Interamericana, 1984, 898-903.

6. KOSHY, M.; WEINER, S. J.; MILLER, S. T. et col and the cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Surgery and anesthesia in sickle cell disease. Blood, 86(10): 3676-84, 1995.

7. SCOTT-CONNER, C. E. H. & BRUNSON, C. D.- The pathophvsiologv of the sickle hemoglobinopathies and implications for perioperative management. Am. J. Surg., 168, 268-274, 1994.

8. VICHINSKY, E. P.; HABERKERN, C. M.; NEUMAYR, L. et col and the preoperative transfusion in sickle cell disease study group. A comparison of conservative and aggressive transfusion regimens in the perioperative management of sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med., 333(4): 206-13, 1995.

9. VICHINSKY, E. P.; STYLES, L. A.; COLANGELO, L. H.; WRIGHT, E. C.; CASTRO, O.; NICKERSON, B. and the cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: clinical presentation and course. Blood, 89(5): 1787-92, 1997.

10. VIPOND, A. J. & CALDICOTT, L. D. -Major vascular surgery in a patient with sickle cell disease. Case report. Anaesth, 53: 1199-1208, 1998.

11. WALDRON, P.; PEGELOW, C.; NEUMAYR, L.; HABERKERN, C.; EARLES, A.; WESMAN, R.; VICHINSKY, E. -Tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, and myringotomy in sickle cell disease: perioperative morbidity. Preoperative transfusion in sickle cell disease study group. J Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol., 21:129-35,1999.

* Physician and Preceptor of Medical Residence of the Service of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/ RJ.

Study conducted at the Service of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho (HUCFF), da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) /RJ.

Address for correspondence: Dra. Marise da Penha Costa Marques - Rua Santa Clara, 70/1101 - Copacabana - 22 041-010 Rio de Janeiro/ RJ - Tel/fax (55 21) 255-6365.

E-mail: marise@rionet.com.br

Article submitted on February 15, 2000. Article accepted on June 9, 2000.