IntroductionThe concern with the quality of life of cancer patients has been increasing over the last decades. Little evolution occurred in terms of survival rate, but many of the techniques were developed with the purpose to mitigate the impact of routine practices on such patients. In larynx and hypopharynx cancer the speech impairment is the most important therapeutic sequel hindering the patient to come back to normal social life. In spite of all major developments in chest surgeries, in partial and subtotal laryngectomy and in radiotherapy and chemotherapy protocols, total laryngectomy remains the most common procedure in the treatment of advanced stage tumors.

Traditional speech rehabilitation techniques in patients that have undergone laryngectomy demonstrated significant disadvantages that could not be overlooked if the goal is to provide better chances of patient re-adaptation to social-family environment. The learning of esophageal speech is not always achieved and success rates may be hindered, if we use as denominator not those patients under training, but all patients subjected to laryngectomy. We know that a significant share of our patients will not be able to undergo speech therapy sessions due to geographical, social and economic issues. Also, in good technical results the voice obtained often have an unpleasant sound and has limited expression potential. The use of electronic larynx does not require intensive training and rehabilitation is obtained in a high percentage of patients, but the quality is poor and the sound produced by the patient is robot-like. The speech does not have patterns and misses emotional content. The patient is dependent on the device and it has also a high cost of use.

These deficiencies have encouraged research methods to get as closer to the ideal situation as possible. Expectations are as follows: to achieve rehabilitation that enables the acquisition of good quality voice in an increased number of patients that not affect cancer therapy; to prevent aspiration in such a way that the patient could be kept only in oral feeding; to be widely recommended, and make the use of hands in vocalizing unnecessary; to occur at the earliest stage possible requiring minimal care and post-operative training; to have low cost and to be compatible with post-operative radiation when it is indicated; and not to require the use of prosthetic devices. This ideal technique does not exist yet.

The surgical alternatives of speech rehabilitation could be divided into three groups: subtotal laryngectomy, tracheoesophageal shunts with prosthetic devices and tracheoesophageal shunts without prosthetic devices. We highlighted in subtotal laryngectomy the near total laryngectomy proposed by Pearson in 19802 and the supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy or cricohyoidoepiglottopexy3. In spite of providing satisfactory outcomes with good quality of voice, these techniques should be clearly and precisely indicated and their use is limited only to some laryngectomy-selected patients4.

The second group uses valve prosthetic devices in the tracheoesophageal shunt after total conventional laryngectomy as advocated by Blom-Singer5 and Paje6. These techniques became very popular in the USA due to its simplicity and easiness to be learned. However, specific care should be given to patients with prosthetic devices and it requires periodical change with consequent increase in cost. Patient low social-educational level and money restraints have limited considerably the application of such techniques in our environment.

Among the tracheoesophageal shunts without using valve prosthetic devices, Amatsu's technique is the most interesting one. The neo-sphincter mechanism that is created during the making of the shunt7 decreases aspiration risk. The quality of rehabilitation achieved is considerably higher than that achieved with conventional techniques8. Still, the procedure could be performed in practically all laryngectomy candidate patients. It is completely contraindicated if there is involvement of the trachea due to subglottis extension of neoplasm9. Other related contraindications are decreased lung reserve to the extent of not having enough airway pressure to produce the voice and in case the patient is not motivated to use the voice.

Because of the low costs of the technique and the good outcomes achieved since the beginning of our study in 199110, tracheoesophageal shunt of Amatsu became our primary alternative for speech rehabilitation in patients that have undergone laryngectomy 11. The objective of this paper is to review our experience with the technique within this 10-year period.

Material and MethodFifty-four patients (54) underwent Amatsu tracheoesophageal shunt from 1991 to 2000 together with total laryngectomy. Three (3) patients were female and fifty-one (51) were male from 30 to 78 years old (mean age was 59 years). All patients were diagnosed with upper airway-digestive tract squamous cell carcinoma; 10 originated in the pyriform sinus; 02 in the retrocricoid region; 06 in the supraglottis region; 01 in the subglottis; 16 in the glottis; and 19 were transglottic tumors.

With reference to the "American Joint Committee on Cancer" (AJCC) staging of 199212 three (3) patients were stage II, 17 stage III, 24 stage IV and in 10 cases data were not enough to make an accurate staging. In terms of primary lesions (T), 05 were T2, 18 were T3, 21 were T4 and in 8 cases it was not possible to make the staging. In terms of neck (N), 32 were N0, 5 were N1, 4 were N2, 2 were N3 and in 9 cases it was impossible to make the staging. The major reasons that hindered the correct staging were secondary alterations from previous treatment and incomplete data in the patient's chart.

Eighteen (18) patients received radiation as a first treatment. Then, due to lack of control or tumor recurrence the patient was referred to salvage surgery.

Thirty-three (33) patients underwent neck dissection, 18 unilateral and 15 bilateral. Five (5) patients needed myocutaneous pectoral flap and one (1) patient needed deltopectoralis flap. Twenty (20) patients received post-operative additional radiation therapy.

The technique has 6 basic steps: making of the posterior tracheal flap, bilateral elevation of the flap to the muscle wall of the esophagus, latero-lateral tracheoesophageal anastomosis, making of the tracheoesophageal shunt, approximation of the esophagus muscle flaps and the closing of the hypopharynx performed as follows:

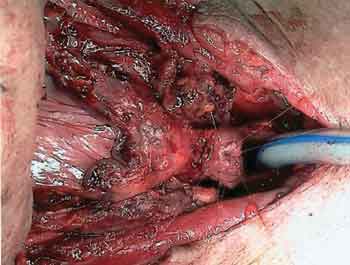

1) Making of the posterior tracheal flap (Figure 1): After ablative surgery, the posterior part of the trachea is spared (it corresponds to a membranous portion) from the cricoid until the fourth tracheal ring, using caution to keep the posterior tracheal flap fixed to the esophagus. The size of this flap is approximately 2.5 cm wide and 4 cm long. The inferior circle of the tracheostoma is sutured to the skin at this time.

2) Elevation of the bilateral flap of the esophagus muscle wall. The exposure of the lateral wall of the esophagus by blunt dissection of the thyroid lobes. Making of a muscle flap encompassing both the longitudinal layer and the circular layer of the esophagus, with caution not to violate the mucosa. This flap should be 5mm wide by 15 mm long with inferior pedicle.

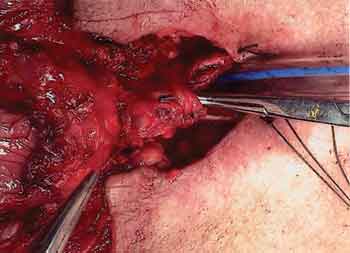

3) Latero-lateral tracheoesophageal anastomosis (Figure 2): With the first finger placed against the posterior wall of the tracheal flap through pharyngotomy, make a 8 mm longitudinal incision beginning 3 mm of the upper rim of the flap. The esophagus mucosa undergoes traction with this incision, and then it is opened and sutured to the tracheal mucosa with simple 5-0-catgut.

4) Making of tracheoesophageal shunt: The lateral rim of the trachea posterior flap is sutured together in the supero-inferior direction making a tube covered with mucosa between the tracheoesophageal anastomosis and the tracheostomy.

5) Approximation of the muscle flaps of the esophagus (Figure 3). The muscle flaps of the esophagus are sutured over the shunt in an inferior position to the tracheoesophageal anastomosis creating a sphincter mechanism. Three to four sutures are used with single nylon 3-0, and the first suture is attached to the shunt.

6) Closing of the hypopharynx: At this step, the hypopharynx is closed in the conventional way, after placement of the nasogastric tube.

The parameters studied were: death, post-operative fistula, local infections, vocalization through the shunt, management of unsuccessful cases and number of surgeries performed in the two sets of 5 year-periods studied.

Figure 1. Making of the posterior tracheal flap (Figure 1): After ablative surgery, the posterior part of the trachea is spared (it corresponds to a membranous portion) from the cricoid until the fourth tracheal ring.

Figure 2. Latero-lateral tracheoesophageal anastomosis (Figure 2): The esophagus mucosa is pulled with this incision, and then it is opened and sutured to the tracheal mucosa with simple 5-0-catgut.

Figure 3. Sphincter mechanism: The muscle flaps of the esophagus are sutured over the shunt in an inferior portion to the tracheoesophageal anastomosis.

One (1) patient died in the early post-operative period due to clinical problems. Fifteen patients had post-operative fistula and four patients had local infection. Therefore, we had the incidence of 36% post-operative local infection processes. All evolved to good outcome.

Seven patients were lost during follow-up and could not be assessed for functional results of the technique. Thirty-two patients developed vocalization through the shunt totaling 70% of the patients that could be assessed. The quality of vocal rehabilitation achieved was increasingly higher than that obtained with non-surgical methods, as reported in the former study. 11,13 The unsuccessful cases were subjected to other rehabilitation techniques without any limitations.

Ten patients had shunt aspiration during oral intake. In most of the cases the aspiration occurred only during fluid intake and was easily controlled by feeding education (fluid intake in small amounts) and by shunt compression during swallowing. Only two patients had to close the shunt surgically. The option of closing the shunt was due not only to aspiration, but also to the fact that both did not have good speech rehabilitation with the technique. Surgical occlusion was performed in outpatient setting under local anesthetic drug.

The division of the study time period by two demonstrated that 36 cases were performed in the first 5 years and 18 cases in the last 5 years.

DiscussionWide indication of the technique was evidenced in our material and it included patients with a broad age range with different clinical staging that have undergone radiation, and were candidates to neck dissection and/or post-operative additional radiation.

Local infections occurred mainly with those patients with primary tumors of the hypopharynx or extended to it, or to patients that received former radiation treatment, known as a risk for such complications14.

The studied group had high rate of advanced stage IV tumors (55%). Most of the patients (70%) underwent radiation, 33% received former radiation and 37% received additional post-operative radiation. Neck dissection related to laryngectomy was performed in 61% of the patients. Six patients (11%) needed a distant flap rotation for reconstruction. In spite of all these limiting factors to any speech rehabilitation technique, the success rate achieved with this technique was 70%, which was highly satisfactory in our opinion. Prevalence of aspiration was 22%, but significant prevalence of aspiration requiring surgical repair was about 4%.

In our opinion, the major advantages of this technique were the following: wide indication, good voice quality, high success rate, low aspiration rate, additional radiation compatibility, does not require the use of prosthetic device and is an easily learned process. 13

Major disadvantages were the following: need to use the hands for vocalization, and the procedure is only performed primarily with laryngectomy. If the patient had undergone laryngectomy in another health care center, it was not possible to secondarily make the shunt. The use of the hands during speech could be eliminated with the use of tracheostoma valves. 15

The decrease of the performance of the procedure in our service comparing the first 5-year experience with the last 5-year term could be credited to several factors. There was higher indication and performance of partial and subtotal procedures such as supracricoid laryngectomy and CO2 laser endo-oral procedures. Moreover, the protocols to spare the organ associated to chemotherapy and radiation increased in our center16. Another key factor was the change in patient's profile care in our service with a decrease in public health care patients and increase in the private health care patients. The increase in social-economic status of the treated population dropped the rate of advanced stage tumors indicated to laryngectomy.

ConclusionIn face of the good results achieved and the few complications, the Amatsu tracheoesophageal shunt remains after 10 years of its introduction in our service as the major speech rehabilitation technique for laryngectomy patients.

REFERENCES 1. Leonard R. Speech Rehabilitation. In: Donald P. Head and Neck Cancer, Management of the Difficult Case. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1984.

2. Pearson BW, Woods RD, Hartman DE. Extended hemilaryngectomy for T3 glottic carcinoma with preservation of speech and swallowing. Laryngoscope 1980;90:1904.

3. Laccourreye H, Laccourreye O, Weinstein G, Menard M, Brasnu D. Supracricoid laryngectomy with cricohyoidopexy: a partial laryngeal procedure for selected supraglottic and transglottic carcinomas. Laryngoscope 1990;100:735.

4. Vieira MBM, Maia AF, Ribeiro JC. Reabilitação Vocal Após Laringectomia "Near Total". Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia 1993;59(2):109.

5. Singer M. Vocal rehabilitation following laryngeal cancer. In Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Shuller D. (ed.) Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. St. Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1986.

6. Panje WR. Prosthetic vocal rehabilitation following laryngectomy. Ann Otol 1981;90:116.

7. Amatsu M, Makino K, Tani M, Kinishi M, Kokubu M. Primary Tracheoesophageal Shunt Operation for Postlaryngectomy Speech with Sphincter Mechanism. Ann Otol 1986;95:373.

8. Amatsu M, Kinishi M, Jamir J. Evaluation of Speech of Laryngectomees after the Amatsu Tracheoesophageal Shunt Operation. Laryngoscope 1984;94:696.

9. Amatsu M. A one stage surgical technique for postlaryngectomy voice rehabilitation Laryngoscope 1980;90:1378.

10. Vieira MBM, Maia AF, Ribeiro JC, Bernardes GS. Shunt traqueoesofágico de Amatsu: Resultados Preliminares. Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia 1993;59(3):189.

11. Vieira MBM, Maia AF, Ribeiro JC. Speech rehabilitation after laryngectomy with the Amatsu tracheoesophageal shunt. Auris Nasus Larynx 1999;26:69-77.

12. Weymuller EA. Head and neck cancer staging. In: Cummings C, Fredrickson J, Harker L, Krause C, Shuller D (eds.). Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Up date I. St. Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1995. p.1-10.

13. Vieira MBM, Maia AF, Ribeiro JC, Bernardes GS, Gama ACC. Reabilitação vocal com o shunt traqueoesofágico de Amatsu em pacientes de língua portuguesa. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço 1994;18(2/3):69.

14. Conley JJ. Oropharyngocutaneous fistula. In Conley JJ (ed.). Complications of head and neck surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders Company; 1979.

15. Blom ED, Singer MI, Hamaker RC. Tracheostoma valve for postlaryngectomy voice rehabilitation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1982;91:576.

16. Wolf GT et al. Induction Chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 1991;324(24):1685.

1 Head of the Clinic of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Hospital Felício Rocho.

2 Clinical Director, Hospital Felício Rocho.

3 Assistant Physician, Clinic of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Hospital Felício Rocho.

4 Resident Physician, Clinic of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Hospital Felício Rocho, Belo Horizonte.

Address correspondence to: Avenida do Contorno, 9215 Sala 802 - 30110-130 - Belo Horizonte - MG - Tel (55 31)291.8288 - Fax (55 31) 337.5398

Article submitted on October 30, 2001. Article accepted on May 23, 2002