IntroductionCongenital absence of the nose, also called by the term arhinia or congenital nasal atresia, is a very rare malformation rarely described in the medical literature2. It is normally associated to other malformations, especially of the central nervous system, and present high rate of mortality7.

The first case was described in 1903 by Wahby12, who noticed the absence of nasal bones and pre-maxilla upon the examination of a skull of the collection at the Museum of the University of Cambridge. Since then, about twenty cases of the malformation have been reported in the medical literature7 in English.

According to Rosen10, congenital absence of the nose can be classified as arhinia and total arhinia, being the former characterized by absence of the nasal pyramid and the latter by absence of the nose associated to agenesis of the olfactory system.

Each case of arhinia deserves careful study because it is a very rare malformation that still does not have clearly defined etiology and treatment.

Case reportThis is the case report of a black male child aged 2 years. The child had been seen in a different service and was referred to us for thorough assessment of facial malformation.

The mother, aged 35 years, had other 6 children with no malformation or other significant affections. Even though she had not had prenatal follow-up, she did not refer events during the 40-week gestation. She did not refer consanguinity with the father, previous diseases (diabetes, arterial hypertension, endocrinopathies), alcohol abuse, smoking, previous abortions and cases of malformation in the family.

The delivery was on February 16, 1997, spontaneous and vaginal, and the newborn cried right after birth, then progressing to cyanosis and respiratory difficulties, immediately submitted to orotracheal intubation. Upon the physical examination, he presented complete absence of the external nose and bilateral microphthalmia. For the first month of life, he remained under intensive care, early tracheostomized, in order to prevent respiratory complications, since the hospital had no resources to perform definite repairing surgery.

In April 1999, the 2-year-old child was seen in our service and we noticed (Figure 1): complete absence of nasal pyramid, replaced by a flat and smooth structure of hardened consistency, high hard palate, normal lips and labial filter, normal otoscopy, bilateral microphthalmia and absence of motor or cognitive deficit. He presented amaurosis, but audiometric, feeding and communication assessments were normal.

During the follow up, we removed the tracheostomy canulla 2 months after receiving the patient, and the tracheostoma healed spontaneously. We performed radiological studies using paranasal sinuses computed tomography scan (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Paranasal sinuses CT (Figures 2 and 3) showed agenesis of nasal pyramid; residual nasal cavity observed as a small space on the superior portion of the maxillary bone filled with soft part density material; high hard palate with a small cleft and presence of soft palate limited by a tiny nasopharyngeal space posteriorly. We also noticed absence of naso-lachrymal ducts, paranasal sinuses and bone failures in the skull base. Ocular globes had reduced dimensions with deformities of the posterior walls and calcification on the left. In the topography of the lachrymal sacs we found two cystic formations of approximately 1.5cm, suggesting the diagnosis of mucocele.

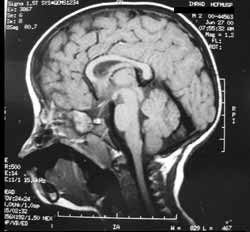

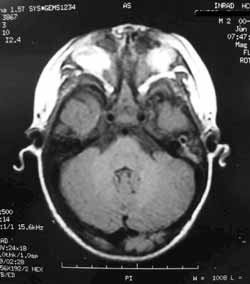

MRI of the face and skull (Figures 4, 5 and 6) showed, in addition to the above mentioned deformities, lowering of the basal frontal gyrus on the topography of the ethmoid fovea, with the remaining encephalic structures without deformities.

Right now, the child is waiting for joint surgery by the teams of Otorhinolaryngology and Plastic Surgery, in order to reconstruct the external nose and to create an airway communication up to the rhinopharynx.

Figure 1. Photograph of the child in profile.

Figure 2. Computed tomography of paranasal sinuses: coronal section at bone window.

Figure 3. Computed tomography of paranasal sinuses: axial section at bone window.

Figure 4. Magnetic resonance imaging of the face: sagittal section at T1.

Figure 5. Magnetic resonance imaging of the face: coronal section at T2.

Figure 6. Magnetic resonance imaging of the face: axial section at T1.

The first development of the face starts from the beginning of the 4th week of embryological activity around the stomodeum (primitive mouth), which is located on the 1st branchial arch. Fronto-nasal prominence (FNP), situated right above the stomodeum, originates the nose and the frontal region of the face. By the end of the 4th week, there are bilateral thick portions of ventral-lateral ectoderm of FNP (nasal placodes) and through the proliferation of mesenchyma on the margins of the placodes, a structure in horseshoe shape is formed, which can didactically be divided into medial and lateral nasal prominence. On the center of the placode, we can notice a depression known as nasal fossula, which represents the beginning of the nostril and the nasal cavity. The naso-lachrymal duct develops as of the thickness of the ectoderm (in a rod shape) on the floor of the naso-lachrymal sulcus, which deepens into the mesenchyma joining the lachrymal sac to the nasal cavity. Between the 7th and the 10th weeks there is the fusion of the medial nasal prominence, forming the upper lip filter, and the formation of primitive choanae through the nasal fossulae, which deepen and originate the oronasal membrane8.

According to Meyer7, arhinia is the result of a failure in the development of nasal placodes. The naso-lachrymal ducts are initially formed, but they end in a dead end, since they can not communicate with the nasal cavity. The palate assumes an arched and high aspect not only because of lack of nasal cavity, but also because of absence of nasal septum growth, which contributes to normal formation of secondary palate. The olfactory epithelium, as predictable, is not formed in the absence of nasal fossula invagination, leading to hypoplasia of olfactory bulbs and anosmia.

Associated ocular deformities are rare and probably caused by the underdevelopment of the naso-lachrymal system13. The exact etiology of this associated malformation is not clear and maybe it is even more complex, since there are literature reports of isolated arhinia2, 4, 7, 11.

DiscussionEven though there are some theories based on embryology that explain congenital absence of the nose, no etiological cause has been convincingly explained so far. According to a study of 12 arhinia cases, Cohen3 noticed that the main associated factors were maternal diabetes (2 cases), polyhydramnios (2 cases), chromosome 9 anomaly (2 cases) and history of maternal bleeding at the beginning of the gestation (2 cases). As to our patient, we can not assure there was a chromosome 9 anomaly because we did not perform karyotype studies; however, we are positive he did not present any of the other factors, similarly to the case reported by Cole4.

It is important to notice that following the classification suggested by Rosen10, we can define our case as total arhinia, since there was no signs of formation of olfactory bulbs and nerves.

The imaging studies are extremely important to analyze the congenital absence of the nose. Diagnosis can be made before delivery, as demonstrated by Cusick5 in serial ultrasound exams that indicated the defect upon the study of the profile of the fetus. CT scan can show bone abnormalities and delimit the margins for the surgical act, whereas MRI helps in the differentiation of the soft part tissues, which occasionally are mistaken by encephalocele. The first assessment using these two exams happened in 19894 and since then, all cases have been studied with them.

Some anatomical abnormalities seen in our patient had already been described, especially the anterior bone stenosis 1, 4, 7, 9, hypoplastic nasal cavity4, high palate4, 7, 9 and cleft palate13, naso-lachrymal duct agenesis6, 9, paranasal sinuses hypoplasia 4, 9, and microphthalmia 13. Other characteristics present in the medical literature, however, were not found in our case: bone cleft on the cribrosa lamina and sphenoid plan4 and presence of maxillary sinus7. The unique findings in our patient consisted of two cystic formations located on the topography of the lachrymal sacs, which we suspected of mucocele and calcifications found inside the left ocular globe.

In general, face and skull MRI demonstrate normal parameters of the central nervous system, except for the olfactory system, which is hypoplastic most of the times1.

As to treatment, since the first attempt of surgical correction2, most authors have decided to perform esthetical and functional repairing surgical treatment or only to restore physiological airways (neo-cavity)4. Many authors prefer to address the anatomical problem differently, instead of having a tracheostomy. This first approach is normally performed in the first month of life, with reports that vary from 15 days4 to 2 months13.

The surgical technique is still not fully defined yet and varies significantly, as we could notice in the reports by Meyer7 and Mühlbauer9. The former conducted nose reconstruction in three surgical times, being the first one the creation of the external nose, using a cutaneous flap from the frontal region with inferior basis, positioned over the nasal agenesis, in order to recover the graft of costal cartilage that sustained the neo-septum structure. The second intervention was made 45 days later and it opened bone passages, leaving a septum between them except in the choanal region, which were connected to communicate. The last surgery was made in order to expand the nasal fossae. Mühlbauer9, in turn, first implanted 2 expanders under the skin of the agenesis region. Two months later, we opened the nasal fossae and proceeded to the reconstruction of the nasal pyramid in one surgical time. His technique started with bone drilling, forming two cavities. Right after, he made two incisions in the expanded skin, in order to design the nostrils and the columella, and a flap of frontal bone plus periosteum was placed on the defected region, in order to maintain the architecture of the external nose.

The current trend is to treat surgically all cases before school age, because even though the patients can be fed and breathe using the oral route6, we should try to minimize future psychological traumas that could definitely arise from it.

closing remarks Arhinia is an extremely rare malformation that is normally manifested by significant respiratory difficulty, requiring quick life support intervention (orotracheal intubation or tracheostomy). Radiological investigation helps the determination of the exact anatomical abnormalities and consists of paranasal sinuses CT and face and skull MRI. This developmental defect can pose risk to the life, but surgical approach can be elective since the child adapts to oral breathing.

REFERENCES1. ALBERNAZ, V.S.; CASTILLO, M.; MUKHERJI, S.K.; IHMEIDAN, I.H. - Congenital arhinia. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.; 17(7): 1312-4, 1996 Aug.

2. COHEN, D.; GOITEIN, K. - Arhinia. Rhinology; 24: 287-292, 1986.

3. COHEN, D.; GOITEIN, K. - Arhinia revisited. Rhinology, 25: 237, 1987.

4. COLE, R.R.; MYER III, C.M.; BRATCHER, G.O. - Congenital absence of nose: a case report. Int. J. Pediatric Otolaryngol.; 17: 171-178, 1989.

5. CUSICK, W.; SULLIVAN, C.A.; ROJAS, B.; POOLE, A.E.; POOLE, D.A. - Prenatal diagnosis of total arhinia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol.; 15(3): 259-61, 2000 Mar.

6. GALETTI, R.; DALLARI, S.; BRUZZI, M.; VINCENZI, A.; GALETTI, G. - Considerazioni di fisiopatologia respiratoria a proposito di un casi di arinia. Acta Otorhinol. Ital.; 14: 63-69, 1994.

7. MEYER, R. - Total external and internal construction in arhinia. Plast. Reconstr Surg.; 99 (2): 534-542, 1997.

8. MOORE, K.L.; PERSAUD, T.V.N. - Embriologia clínica, Quinta edição, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Guanabara Koogan S. A., 1994, 177-213.

9. MÜHLBAUER, W.; SCHMIDT, A.; FAIRLEY, J. - Simultaneous construction of an internal and external nose in an infant with arhinia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.; 91 (4): 720-725, 1993.

10. ROSEN, Z. - Embryological introduction to congenital malformations of the nose. Int. Rhinol.; 1: 10, 1963.

11. SMITH, D.W.; DICKSHEET, S. - Reconstruction of agenesis of the external nose secondary to congenital hypertelorism. Clinics Plastic. Surg.; 8 (3): 615-618, 1981.

12. WAHBY, B. - Congenital absence of the nose and premaxilla. J. Anat. 38: 49, 1903.

13. WEINBERG, A.; NEUMAN, A.; BENMEIR, P.; LUSTHAUS, S.; WEXLER, M.R. - A rare case of arhinia with severe airway obstruction: case report and review of the literature. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.; 91 (1): 146-149, 1993.

[1] Resident Physician, Discipline of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

[2] Post-Graduate studies under course, Discipline of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

[3] Ph.D., Professor, Discipline of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

[4] Associate Professor, Discipline of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

Study conducted at the Division of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas, Medical School of the University of São Paulo.

Address correspondence to: Daniel Chung

Av. Dr. Enéas de Carvalho Aguiar, 255 - 6°andar - sala 6021

05403-000 - São Paulo - SP - Tel: (55 11) 3069-6288 Fax: (55 11) 270-0299.