INTRODUCTIONOsteomas are benign neoplasms and the most common tumor in the paranasal sinuses. The incidence varies from 0.43% to 3%4, 5, and it is normally located in the frontal sinus (57%)6, followed by ethmoidal, maxillary and, rarely, sphenoid sinuses.

Etiology of osteomas is controversial and still unknown, and the most widely accepted theories are embryological, traumatic and infectious. According to the embryological theory, osteomas are originated in the suture lines between the areas of endochondral and membranous ossification. The bones that form the skull base originate from the endochondral ossification; the orbital portion of the frontal bone, the lateral portion of the sphenoid bone and the skull bones originate from the membranous ossification6. The traumatic theory suggests that osteomas are originated from small bone sequestration resultant from injury. According to the infectious theory, there is a secondary osteogenic stimulus to the infectious process.

The clinical picture of fronto-ethmoidal osteomas is a result of its slow growth and depends on its location. Most of them are found in simple facial x-rays, and only 10% are symptomatic7. The most common symptom is frontal headache or facial pain, followed by signs or symptoms related to growth within the limits of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses (diplopia, proptosis, esthetical deformity, sinusitis, amaurosis, intracranial aerocele and meningitis).

In the present paper, we present a group of 9 patients with frontal and ethmoidal osteomas, aiming at discussing clinical presentation, diagnosis and the surgical techniques most appropriate to manage the disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODWe conducted a prospective clinical study with a group of nine patients with radiological and histopathological diagnosis of frontal or ethmoidal sinus osteoma, operated on at Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual de São Paulo - Francisco Morato de Oliveira, and at Hospital São Luiz - São Paulo - SP, between 1995 and 1999. We recorded age, sex, most frequent symptoms, complementary tests: simple x-rays and paranasal sinuses computed tomography (Figures 1 and 2), location, size, surgical technique, treatment complications and progression (Table 1).

Table 1. Data of patients with fronto-ethmoidal osteoma.

We noticed that out of 9 studied cases, four were male and five were female subjects, ages ranging from 12 to 55 years, mean age of 39.55 years. In this group, three patients had history of sinusitis (33.3%). The most frequent symptom was headache (88.8%), followed by nasal obstruction and diplopia. The most frequent location was frontal sinus (66.6%), and osteomas were predominantly smaller than 3cm (55.5%). Smaller tumors were more frequent in the frontal sinus (80%) and when larger than 3cm, 50% of them were in the ethmoidal sinus.

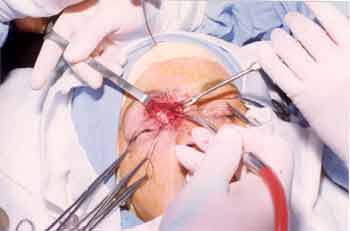

For tumors located in the frontal sinus, the preferred surgical approach was frontal bone osteoplasty technique, from a coronal or supraciliary incision (Figure 3). For anterior ethmoidal sinus tumors, owing to size of lesion, we used external ethmoidectomy, starting from Lynch incision (Figure 4). The occurrence of postoperative sequela (hyposmia and diplopia) was observed in one case, probably a result of the location of the osteoma in the anterior ethmoidal sinus and the size of the lesion (> 3cm). This case had already reported preoperative diplopia.

Figure 1. Computed tomography, paranasal sinuses, axial section, showing frontal sinus osteoma located close to nasofrontal duct (Case 6).

Figure 2. Computed tomography of paranasal sinuses, axial section, showing anterior ethmoidal sinus compressing the papyraceous lamina and the orbital content (Case 7).

Figure 3. Osteoma located on the inferior and medial region of frontal sinus, after sinusectomy through osteoplasty technique (Case 6).

Figure 4. Removal of ethmoidal osteoma using Lynch incision (Case 7).

Osteomas are benign tumors, of slow growth and mature bone tissue aspect. It is the most common benign nose and paranasal sinuses tumor8. Its incidence is rare and unknown, since most of the cases are asymptomatic and left undiagnosed. Childrey, in 1939, based on a serial analysis of 3,510 simple x-rays of paranasal sinuses found an incidence of 0.43%1. Mehta and Grewal (1963) assessed 5,086 paranasal sinuses simple x-rays in subjects with sinusal symptoms and found osteoma-suggestive lesions in 1% of this population (50 cases)4, 8. Earwalker in 1993 studied 1,500 paranasal sinuses CT scans and found 46 (3%) radiological lesions compatible with osteomas, but only two subjects were symptomatic5.

They are more frequent in males, ranging from 1.3:1 to 2.6:18, 9, and the literature does not present any reason to justify this prevalence. In our sample, we noticed greater frequency in female patients, in a 0.8:1 ratio. The most common age for presentation is between the second and fourth decades of life8,9. In our series, it varied from 12 to 55 years, mean age of 39.55 years.

As to site of origin, the frontal sinus is the most frequent one (80%)5, followed by ethmoidal, maxillary and, more rarely, the sphenoid sinus8, 9, 10, 11. We observed in our patients that 66.6% were cases of frontal sinus osteoma.

Etiology of osteomas is controversial and not fully understood yet, but there are three classical theories: embryological, traumatic and infectious. According to the embryological theory, tumors are originated from the junction between endochondral bones (orbital portion of the frontal bone, lateral portion of sphenoid major ala, and skull base bones) and membranous bones (bones that form the skullcap). As a result, osteomas tend to be formed in the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses6. The traumatic theory proposed that osteomas are formed by small bone sequestration resultant from injury, based on the fact that 30% of the cases have history of head trauma8, 9. Chronic infection has been suggested as a possible factor for the origin of osteomas, based on the stimuli to fibroblast proliferation. However, high incidence of sinusal infection compared to the rarity of osteomas makes this theory less probable than the other two8, 12. There is a condition in which we can see the association of intestinal polyposis and tendency to malignant transformation, dermoid cysts, paranasal sinuses fibromas and osteomas, denominated Gardner's syndrome. It is a hereditary autosomal dominant disease with complete penetration and variable expression, and it should be considered whenever we face a case of osteoma 13.

Histopathologically, osteomas are classified as compact or spongy, and they may occur in specific cases, with variable proportion and predominance of one or the other component. Compact osteomas originate from membranous ossification and spongy ones from endochondral ossification8. They present a trend of slow growth, estimated in 1.16mm/year, ranging from 0.44 to 6.0mm/year10.

Most of the osteomas are asymptomatic and clinical presentation of these lesions depends basically on site of origin. The most frequent symptoms are frontal headache or facial pain, followed by mucopurulent rhinorrhea. Other symptoms are present when the osteoma exceeds the limits of the frontal or ethmoidal sinus, leading to orbital complications (diplopia, proptosis, palpebral ptosis, fugax amaurosis, epiphora, and acquired Brown's syndrome), which are not frequent despite the two third of cases that suffer extension up to the orbit14, 15. There is a series of reports of cases of intracranial complications resultant from fronto-ethmoidal osteomas such as meningitis, cerebral abscess, CSF leak, intracranial mucocele and pneumoencephalus 11, 16, 17. Frontal sinus osteoma, when close to the nasofrontal duct, can produce mechanical obstruction, regardless of its size18. We observed in our series that of the three cases with history of sinusitis, two had frontal sinus osteomas with implantation close to the nasofrontal duct (medial implantation), with diameter below 3cm. Headache was the most common symptom, reported in 88.8% of the cases.

According to the literature, it is believed that when the tumor originates from the ethmoidal sinus, the diagnosis is early, owing to smaller size of the sinus and easy access to adjacent structures (orbit and skull)7.

Diagnosis is made based on radiological exam (simple x-ray or paranasal sinuses CT scan). The preferred exam is CT scan, which provides more precise information about size and location of lesion and supports surgical preparation14.

Differential diagnosis includes fibrous osteomas, fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, osteoblastoma, giant cell tumor, osteosarcoma, mucocele, calcified intrasinusal meningioma, hematoma or polyp. Some metastatic tumors (prostate, lung and thyroid cancer) can simulate an osteoma owing to its osteoblastic activity18.

Surgical indication of frontal and ethmoidal sinus osteomas were revised by Savic and Djeric, in 1990, based on the assessment of 61 cases followed up from 1970 to 198819. Small osteomas located in the frontal sinus, laterally to the nasofrontal duct, and asymptomatic are clinically followed for intervals of six months to one year, assessing the growth based on radiological exams17, 19, 20. Surgical treatment is reserved for the following situations:

- osteoma that extends beyond the limits of the frontal sinus;

- when there are signs of growth in serial radiological exams;

- located in the low and medial regions of frontal sinus, adjacent to nasofrontal duct;

- located in the ethmoidal sinus, regardless of size, owing to the risk of obstructing the nasofrontal duct and extending to the orbit;

- associated to signs of chronic sinusitis;

- frontal sinus osteoma in patients with headache, after excluding other causes to the symptom.

Access routes for the surgical treatment depend on location, extension and size of osteomas. For localized lesions of the frontal sinus, the frontal sinus osteoplasty technique is advocated17, 19, described in 1894 by Kocher, Hajek and Schonborn, and spread by Goodale and Montgomery in the 1950 and 1960's21. The location of the coronal or supraciliary incision influences both the intra-operative and the final result. In coronal incisions, there is greater rate of bleeding, but it is preferable from an esthetical standpoint. Supraciliary incision is indicated in bald subjects or those with history of family baldness20, 22. After opening of frontal sinus, we should perform complete removal of osteoma, under the risk of experiencing local recurrence of tumor, despite the low rate of growth. In frontal sinus cases, we decided to follow osteoplasty technique and did not observe intra-operatively complications and had satisfactory esthetical result. We did not obliterate the frontal sinus with fat, as advocated by some authors20.

In the case of osteoma located in well pneumatized frontal sinus we can use an endoscopic approach that enables appropriate visualization and resection from lateral access23.

For ethmoidal and fronto-ethmoidal osteomas, with orbital extension, we can use external ethmoidectomy with Lynch incision19. This was the technique chosen in the three cases assessed by us. Osteomas that are extended deeply towards the anterior cranial fossa, of large dimensions, can be removed from craniofacial approach, with the support of a neurosurgeon6, 19, 24.

Nasal endoscopic surgery has been recently used in the treatment of small ethmoidal osteomas, without extrasinusal extension, or frontal osteomas located in the inferior and medial portion of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus25-27.

CONCLUSIONSParanasal sinuses osteomas are benign tumors, of slow growth that can occasionally be found in asymptomatic patients that are submitted to radiological exams for other reasons.

Owing to the possible complications resultant from its growth and location, surgical indications are made in the following cases: osteoma that extends beyond the limits of frontal sinus; when it presents signs of growth in serial radiological assessments; located in low and medial regions of the frontal sinus, close to the nasofrontal duct; located in the ethmoid sinus, regardless of size, owing to the risk of obstruction of the nasofrontal duct and extending into the orbit; when associated to signs of chronic sinusitis or frontal sinus osteoma in patients with headache, after exclusion of other causes.

Small osteomas located in the frontal sinus, laterally to the nasofrontal duct and asymptomatic, should be clinically followed up, at six-month to one year intervals, assessing the growth based on radiological exams.

REFERENCES1. Childrey JH. Osteomas of the sinuses, the frontal and sphenoid bone. Arch Otolaryngol 1939;30:63-72.

2. Shady JA, Bland LI, Kazee AM, Pilcher WH. Osteoma of the frontoethmoidal sinus with secondary brain abscess and intracranial mucocele: case report. Neurosurgery 1994;34(5):920-23.

3. Rappaport JM, Attia EL. Pneumocephalus in frontal sinus osteoma: a case report. J Otolaryngol 1994;23(6): 430-36.

4. Mehta BS, Grewal GS. Osteoma of the paranasal sinuses along with a case of an orbito-ethmoid osteoma.. J Laryngol Otol 1963;77:601-610.

5. Earwalker J. Paranasal sinus osteomas: a review of 46 cases. Skeletal Radiology 1993;22:417-23.

6. Chang SC, Chen PK, Chen YR, Chang CN. Treatment of frontal sinus osteoma using a craniofacial approach. Ann Plast Surg 1997; 38(5): 455-59.

7. Boysen M. Osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. J Otolaryngol 1978;7(4):366-70.

8. Atallah N, Jay MM. Osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol 1981;95(3):291-304.

9. Samy LL, Mostafa H. Osteoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses with a report of twenty one cases. J Laryngol Otol 1971;85(5):449-69.

10. Koivunen P, Lopponen H, Fors AP, Jokinen K. The growth rate of osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol 1997;22(2):111-4.

11. Hardwidge C, Varma TRK. Intracranial aeroceles as a complication of frontal sinus osteoma. Surg Neurol 1985;24:401-4.

12. Gillman GS, Lampe HB, Allen LH. Orbitoethmoid osteoma: case report of an uncommon presentation of an uncommon tumor. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;117(6):218-20.

13. Jones K, Korzcak P. The diagnostic significance and management of Gardner's syndrome. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 1990;28:80-84.

14. Vowles RH, Bleach NR. Frontoethmoid osteoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1999;108(5):522-4.

15. Biedner B, Monos T, Frilling, Mozes M, Yassur Y. Acquired Brown's syndrome caused by frontal sinus osteoma. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus 1988;25(5):226-29.

16. George J, Merry GS, Jellett LB, Baker JG. Frontal sinus osteoma with complicating intracranial aerocele. Aust N Z J Surg 1990;60:66-8.

17. Shady JA, Bland LI, Kazee AM, Pilcher WH. Osteoma of the frontoethmoidal sinus with secondary brain abscess and intracranial mucocele: case report. Neurosurgery 1994;34(5):920-3.

18. Noyek AM, Chapnik JS, Kirsh JC. Radionuclide bone scan in frontal sinus osteoma. Aust N Z J Surg 1989;59:127-32.

19. Savic DL, Djeric DR. Indications for the surgical treatment of osteomas of the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol 1990;15(5):397-404.

20. Smith ME, Calcaterra TC. Frontal sinus osteoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989;98(11):896-900.

21. Goodale RL, Montgomery WW. Anterior osteoplastic sinus operation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1961;70:860-80.

22. Fobe LP, Melo EC, Cannone LF, Fobe JL. Surgery of frontal sinus osteoma. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2002;60(1):101-5.

23. Al-Sebeih K, Desosiers M. Bifrontal endoscopic resection of frontal sinus osteoma. Laryngoscope 1998;108(2):295-8.

24. Blitzer A, Post KD, Conley J. Craniofacial resection of ossifying fibromas and osteomas of the sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg 1989;115(9):1112-5.

25. Namdar I, Edelstein DR, Huo J, Lazar A, Kimmelman CP, Soletic R. Management of osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Rhinol 1998 12(6):393-8.

26. Huang HM, Liu CM, Lin KN, Chen HT. Giant osteoma with orbital extension, a nasoendoscopic approach using an intranasal drill. Laryngoscope 2001;111(3):430-2.

27. Schick B, Steigerwald C, el Rahman el Tahan A, Draf W. The role of endonasal surgery in the management of frontoethmoidal osteoma. Rhinology 2001;39(2):66-70.

[1] Doctorate studies under course, Head and Neck Surgery and Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP-EPM. Assistant Physician, Service of Otorhinolaryngology, HSPE-FMO.

[2] Cooperating Physician, Division of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clinicas, FMUSP. Former resident, Service of Otorhinolaryngology, HSPE-FMO.

[3] Ph.D. in Medicine, FMUSP. Member of the Post-Graduation Course, Service of Otorhinolaryngology, HSPE-FMO. Otorhinolaryngologist at Hospital São Luiz.

Affiliation: Service of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual - Francisco Morato de Oliveira - São Paulo - SP. Hospital São Luiz - São Paulo - SP.

Address correspondence to: Romualdo S. L. Tiago - Rua Estado de Israel 493, ap 51

Vila Clementino - São Paulo-SP - 04022-001 - Tel. (55 11) 5084-7725. - E-mail: romualdotiago@uol.com.br