INTRODUCTIONCleft lip and/or palate (CL/P)(OMIM 119530) represents the most common of the congenital facial anomalies, making up approximately 65% of all craniofacial malformations1. The incidence of CL/P is approximately 1 in every 500-2,000 live births, varying according to geographic location, race and the very social and economic situation of the population studied2,3. In Brazil, there are only a handful of studies as to the incidence of CL/P, and they vary considerably. According to Brazilian epidemiological surveys, the incidence of CL/P varies between 0.19 to 1.54 for every 1,000 births4-6. It is not known whether this epidemiological difference is real or associated with methodological differences6.

70% of the affected individuals develop non-syndromic CL/P, in other words, without association with other malformations and without behavioral and/or cognitive changes. The remaining 30% are associated with Mendelian disorders (dominant autosomal, recessive autosomal or x-linked), chromosomal, teratogenic or sporadic conditions which include multiple congenital deffects7,8. Even being a common congenital defect, CL/P etiopathogeny is still uncertain9. This is mostly a reflex of the complexity and diversity of the molecular mechanisms involved in embryogenesis, with the participation of multiple genes and the influence of environmental factors10,11.

It is widely accepted that CL/P has a multifactorial etiology, with genetic and environmental components. Among the environment risk factors for CL/P we stress: maternal diet and vitamin supplements, alcohol ingestion, smoking, the use of anti-seizure medication in the first quarter of gestation and maternal age9,11. As to the genetic contribution for CL/P, so far, there are numerous genes investigated, but very few clearly associated with CL/P, such as the PVRL1 (Poliovirus receptor related-1)12, TGF-b3 (Transforming growth factor beta 3)13, MSX1 (Msh homeobox 1)14, TBX22 (T-box 22)15, FGFs (Fibroblast growth factor)16, PTCH (Patched)17, and the IRF6 (Interferon regulatory factor 6)7.

Clinically speaking, CL/P is classified in four groups based on its location in relation to the incisive foramen, as follows: pre-foramen clefts, or simply: labial fissures (LF), post-foramen fissures (PF), trans-foramen fissures or lip-palate fissures (LPF), and rarely facial fissures18. The limited knowledge on the very etiology of CL/P makes it difficult even to describe and to distinguish between the varied forms of presentation of these malformations.

Thus, because of the scarcity of national studies, the goal of the present study was to describe and analyze the clinical traits of the uncommon and rare cases of CL/P in a reference center for craniofacial deformities.

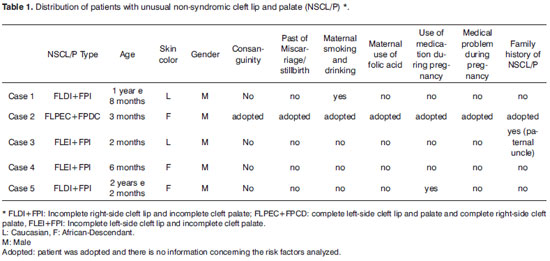

MATERIALS AND METHODSWe carried out a retrospective study between the first semester of 1992 and the 1st semester of 2009, in a reference Ward for craniofacial deformities in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. We assessed the clinical charts from the patients seen during this time interval. The fissure distribution is seen on Table 1. We can notice that of the 778 CL/P cases, only 5 (0.64%) were uncommon, which had an anatomical behavior different from that of usual classifications, in other words, (1) CL: including unilateral or bilateral, complete or incomplete pre-foramen; (2) CLP: including unilateral and bilateral trans-foramen clefts, and pre and post foramen clefts; (3) CP: including all complete or incomplete post foramen clefts and (4) Others: here we find the rare facial clefts18. From this scientific investigation we excluded syndromic patients with CL/P or those who had other uncommon disorders associated with the clefts.

From the clinical charts, besides classifying the CL/P, we also collected the following information: age, gender, a past of consanguinity, maternal smoking and alcohol beverage drinking, the use of medication during pregnancy, use of folic acid in the pre-gestational period and in the first quarter of pregnancy, a past of miscarriages and/or stillbirths, maternal diseases and a Family history of CL/P. all the five patients with unusual CL/P were clinically assessed by two professionals trained in the aforementioned institution. This study was carried out in accordance with the principles established by resolution 196/88 from the National Health Council of the Ministry of Health, besides being approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of our University.

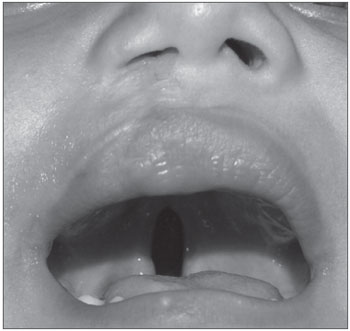

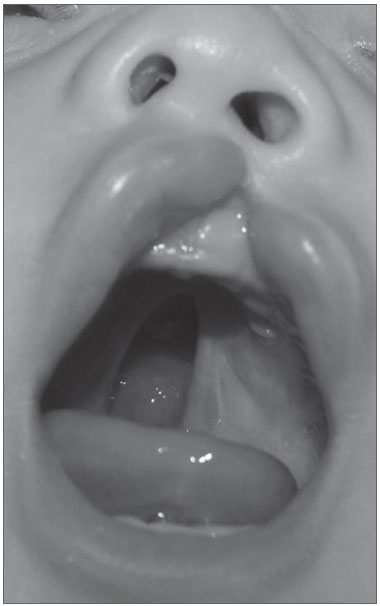

RESULTSAccording to Table 1, of the 778 cases of CL/P, seen between the first semester of 1992 and the end of the first semester of 2009, only 5 (0.64%) patients had unusual CL/P. on this same Table we see that all the 5 patients were males and, the mean age at first consultation in visit to our center was 1 year (varying between 2 months and two years and two months). As far as skin color goes, 3 patients were of brown skin and 2 were whites. Considering the type of cleft, 2 patients had incomplete direct cleft lip associated with the incomplete palate cleft (Fig. 1); 2 had incomplete left cleft lip plus incomplete palate cleft (Fig. 2) and 1 had complete left-side palate cleft plus a complete right-side palate cleft.

Figure 1. Patient with incomplete right-side cleft lip associated with incomplete cleft palate. Notice that the cleft lip has already been operated.

Figure 2. Patient with incomplete left-side cleft lip associated with incomplete cleft palate.

Mean maternal and paternal ages during gestation in these cases of unusual CL/P was of 26 years for both; we excluded the clinical information from 1 patient who had been adopted, thus making it impossible to collect information. There was no past of consanguinity between the couples, maternal ingestions of alcohol and smoking, use of medication during pregnancy, miscarriage and/or stillbirth past and maternal diseases among the five cases of unusual CL/P we analyzed (Table 1). Nonetheless, one case (case 3) was positive for the family history of CL/P. In such case, a paternal uncle had complete bilateral CL/P. All the five patients, as well as family members, were seen at the health care facility and are currently under multi-professional clinical follow up.

DISCUSSIONNumerous epidemiological studies have shown that CL/P has a unique distribution and the incidence of these anomalies varies among the different populations assessed19-23. Thus, the Asian population, ancestors of American natives and northern Europeans have a higher incidence of CL/P1,20 and, contrasting that, Africans and their descendants have a higher incidence of CL alone20. In most of the studies, CLP is the most common among NSCL/P19,20,23,24(Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip/Palate) cases. Nonetheless, the prevalence of CL and CP vary according to the population studied19,22,25-27. A reduced share of the patients with NSCL/P (1-3.6%) had uncommon forms of bilateral clefts, thus encompassing numerous combinations of CL with different degrees of severity in both sides, such as associations of incomplete CL on one side and complete CLP on the other side22,27,28. Thus, in the present study, because of the scarcity of national studies, uncommon and rare forms of CL/P were described and analyzed.

Of the 778 cases of NSCL/P diagnosed in a Reference Ward in Minas Gerais, Brazil, in the 17 year period, only 5 (0.64%) patients had uncommon forms of these anomalies. A study assessing 803 Brazilian patients who were not operated for CL/P, with or without additional malformations and without recognizable syndromes, found a prevalence of 1.9% of bilateral clefts with unusual associations22. In two other studies assessing 835 Mexican patients and 1,669 Iranian patients with CL/P, the uncommon clefts were found in 1% and 3.6% of the cases, respectively27,28. Nonetheless, differently from these papers analyzed, the present study included only NSCL/P, in other words, without alterations or associated syndromes. Thus, the reduced prevalence found in the present study compared to literature indexes22,27,28 can reflect the methodological difference employed in these populations analyzed.

All the 5 patients affected by unusual NSCL/P were males. Considering the relationship between cleft type and patient gender, most of the studies show that CLP is more frequent in males29,30. Nonetheless, considering CL and CP alone, the epidemiological investigations showed controversial results6,25,27,28. Partially corroborating the results found in the present study, as far as gender is concerned, González et al. (2008)27 found the occurrence of unusual CL/P in males, with only one exception.

Bilateral clefts have a relevant morphological variation, with different combinations, but most with limited frequency and, rarely, reported in the literature22. The forms of clinical presentation of the unusual NSCL/P found in the present study were, respectively, incomplete left-side CL associated with incomplete CP (2 cases, 40%); direct incomplete CL associated with incomplete CP (2 cases, 40%) and complete left-side CL/P and complete CP (1 case 20%). It is worth noticing that the most severe form of extension of these NSCL/P was associated in only one case.

Comparing the three major types of NSCL/P (CL, CLP and CP), the distribution of unusual CLP by type (unilateral/bilateral), extension (complete/incomplete) and laterality (right/left), is partially in agreement with the literature because of the predominance of incomplete left-side CL, complete left-side CLP and, incomplete CP in the populations investigated22,24,25,27.

Among environmental risk-factors for CL/P we stress, consanguinity, smoking, alcohol ingestion, use of medication during pregnancy, insufficient ingestion of folic acid in the pre-gestational period and in the first quarter of pregnancy, a past of miscarriage and/or stillbirth, maternal diseases and family history of clefts9,31. Nonetheless, in the present scientific investigation we did not find a positive association between these variables and the uncommon NSCL/P. We stress that no mother reported the use of vitamin supplementation or the ingestion of folic acid in the pre-gestational period and/or on the first quarter of pregnancy and only one patient had positive Family history of orofacial clefts. Having in mind the reduced prevalence of unusual NSCL/P in the different populations, the present study confirms the rarity of such malformations in the Brazilian population, besides stressing the importance of describing and assessing these rare cases in an attempt to better understand their etiopathogeny.

CONCLUSIONThe present study assessed 5 rare or unusual cases of NSCL/P in a Brazilian population and confirmed the limited prevalence of such alterations. The clinical types of these fissures were incomplete unilateral lip fissure associated to incomplete palate fissure and complete unilateral cleft lip and palate and complete cleft palate, and they were all seen in male individuals. Moreover, the unusual NSCL/P cases were not associated to the risk factors evaluated. Investigations concerning the rare forms of NSCL/P may enable a better understanding of the etiopathogeny of orofacial clefts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTFundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (Fapemig) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)(HMJ).

REFERENCES 1. Gorlin R, Cohen M, Hennekam R. Syndromes of the head and neck. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

2. Mitchell LE, Beaty TH, Lidral AC, Munger RG, Murray JC, Saal HM et al. Guidelines for the design and analysis of studies on nonsyndromic cleft lip and cleft palate in humans: summary report from a Workshop of the International Consortium for Oral Clefts Genetics. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39(1):93-100.

3. Slayton RL, Williams L, Murray JC, Wheeler JJ, Lidral AC, Nishimura CJ. Genetic association studies of cleft lip and/or palate with hypodontia outside the cleft region. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003;40:274-9.

4. Nagem Filho H, Moraes N, Rocha RGF. Contribuição para o estudo da prevalência das más formações congênitas lábio-palatais na população escolar de Bauru. Rev Fac Odontol São Paulo. 1968;6:111-28.

5. Loffredo L, Freitas J, Grigolli A. Prevalência de fissuras orais de 1975 a 1994. Rev Saúde Pública. 2001;35(6):571-5.

6. Martelli-Júnior H, Orsi Júnior J, Chaves MR, Barros LM, Bonan PRF, Freitas JA. Estudo epidemiológico das fissuras labiais e palatais em Alfenas - Minas Gerais - de 1986 a 1998. RPG. 2006;13(1):31-5.

7. Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, Daack-Hirsch S, Nepomuceno B, Ribeiro L et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:769-80.

8. Paranaíba LMR, Martelli-Júnior H, Swerts MSO, Line SRP, Coletta RD. Novel mutations in the IRF6 gene in Brazilian families with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22(4):507-11.

9. Vieira AR. Unraveling human cleft lip and palate research. J Dent Res. 2008;87:119-25.

10. Carinci F, Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Zollino I, Pezzetti F. Human genetic factors in nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate: An update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolar. 2007;71(10):1509-19.

11. Martelli DRB, Cruz KW, Barros LM, Silveira MF, Swerts MSO, Martelli-Júnior H. Maternal and paternal age, birth order and interpregnancy interval evaluation for cleft lip-palate. RBOt. 2009 (in press).

12. Sozen MA, Suzuki K, Tolarova MM, Bustos T, Fernandez Iglesias JE, Spritz RA. Mutation of PVRL1 is associated with sporadic, non-syndromic cleft lip/palate in northern Venezuela. Nat Genet. 2001;29:141-2.

13. Vieira AR, Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Cooper ME, Marazita ML, Murray JC. MSX1 and TGFB3 contribute to clefting in South America. J Dent Res. 2003;82:289-92.

14. van den Boogaard MJ, Dorland M, Beemer FA, van Amstel HK. MSX1 mutation is associated with orofacial clefting and tooth agenesis in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;24:342-3.

15. Braybrook C, Doudney K, Marcano AC, Arnason A, Bjornsson A, Patton MA et al. The T-box transcription factor gene TBX22 is mutated in X-linked cleft palate and ankyloglossia. Nat Genet. 2001;29:179-83.

16. Riley BM, Mansilla MA, Ma J, Daack-Hirsch S, Maher BS, Raffensperger LM et al. Impaired FGF signaling contributes to cleft lip and palate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4512-7.

17. Mansilla MA, Cooper ME, Goldstein T, Castilla EE, Lopez Camelo JS et al. Contributions of PTCH gene variants to isolated cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:21-9.

18. Spina V. A proposed modification for the classification of cleft lip and cleft palate. Cleft Palate J. 1973;10:251-2.

19. Vanderas AP. Birth prevalence of cleft lip, cleft palate and cleft lip and palate among races: a review. Cleft Palate J. 1987;24(5):147-53.

20. Moosey PA, Little J. Epidemiology of oral clefts: An international perspective In: Wyszynski DF, editor Cleft lip and palate: From origin to treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. p127-58.

21. Wantia N, Rettinger G. The current understanding of cleft lip malformations. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18(4):147-53.

22. Freitas JA, Dalben GS, Santamaria M Jr, Freitas PZ. Current data on the characterization of oral clefts in Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18:128-33.

23. Jaruratanasirikul S, Chichareon V, Pattanapreechawong N, Sangsupavanich P.Cleft lip and/or palate: 10 years experience at a pediatric cleft center in Southern Thailand. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45(6):597-602.

24. Martelli-Junior H, Porto LCVP, Barbosa DRB, Bonan PRF, Freitas AB, Coletta RD. Prevalence of nonsyndromic oral clefts in a reference hospital in Minas Gerais State, between 2000-2005. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21(4):314-7.

25. Shapira Y, Lubit E, Kuftinec MM, Borell G. The distribution of clefts of the primary and secondary palates by sex, type, and location. Angle Orthod. 1999;69(6):523-8.

26. McLeod NMH, Urioeste MLA, Saeed NR. Birth prevalence of cleft lip and palate in Sucre, Bolivia. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:195-8.

27. González BS, López ML, Rico MA, Garduño F. Oral clefts: a retrospective study of prevalence and predisposal factors in the State of Mexico. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(2):123-9.

28. Rajabian MH, Sherkat M. An Epidemiologic Study of Oral Clefts in Iran: Analysis of 1669 Cases. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000,37(2):191-6.

29. Menegotto BG, Salzano FM. Epidemiology of oral clefts in a large South American sample. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1991;28(4):373-6.

30. Puhó EH, Szunyogh M, Métneki J, Czeizel AE. Drug Treatment During Pregnancy and Isolated Orofacial Clefts in Hungary. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44(2):194-202.

31. Zeiger JS, Beaty TH. Is there a relationship between risk factors for oral clefts? Teratology. 2002;66(3):205-8.

1. MSc in Stomatology -State University of Campinas - Unicamp; PhD student in Stomatology - Unicamp.

2. PhD in Oral Diagnosis - University of São Paulo - USP, Professor of Stomatology - University of Alfenas.

3. MSc in Health Sciences -State University of Montes Claros - Unimontes, Professor of Semiology - Unimontes.

4. PhD in Stomatology - State University of Campinas - Unicamp, Adjunct Professor - State University of Montes Claros - Unimontes.

5. Resident Physician in Plastic Surgery - Professor at the Medical Sciences School - University of Alfenas.

6. MSc in Health - University of Alfenas; Professor at the Dentistry School - University of Alfenas.

7. PhD; Full Professor.

Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde (CCBS) - Universidade Estadual de Montes Claros, Unimontes, Minas Gerais, Brasil

Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro, s/n Vila Mauricéia

Montes Claros MG 39400-000

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - Fapemig

Paper submitted to the BJORL-SGP (Publishing Management System - Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology) on January 11, 2009

and accepted on February 1, 2010. cod. 6758