INTRODUCTIONThe first descriptions of amyloidosis date back from the beginning of 1840. Virchow was the first one to define the substance amyloid, assuming there was similarity with starch or pulp APUD 1.

Amyloidosis is characterized by abnormal extracellular deposition of amyloid in different tissues and organs, normally associated with dysfunction of the involved tissue or organ 2. The cause is still unknown 2.

In the studies by Kyle and Bayrd APUD 1, mean age of impairment was 61 years, with male predominance (63% men and 56% women), which was also confirmed by Kerner et al.1.

Amyloidosis may be divided into systemic and localized forms. Even though there had not been a satisfactory division for the systemic classification, it was divided into 2: (1) primary, (2) amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma (MM), (3) secondary. (4) hereditary-familiar amyloidosis.

Primary amyloidosis is a systemic form without identifiable cause factor. Secondary amyloidosis refers to systemic amyloidosis concomitantly to chronic diseases such as tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, among others.

Other subclasses of systemic amyloidosis affect patients with MM, who are affected by high incidence of amyloidosis (10 to 20%).

In the localized form, which is extremely rare 3, there is no evidence of systemic amyloidosis or chronic underlying disease. They are sites already described as possible amyloid deposits: bladder, tongue, skin, Waldeyer's ring, hard palate, salivary glands, peripheral nerves, larynx, lungs, among others 4 APUD 1. Tongue (63%) and larynx (19%) are the preferred sites for head and neck amyloidosis, as reported by Kerner et al.1.

There is no satisfactory treatment for systemic amyloidosis 2, and the literature suggests tongue reduction when amyloidosis macroglossia is present 5.

CASE REPORTMale 71-year-old patient born in Sao Paulo, reported history of swallowing difficulties initially with solid foods, which had quickly progressed to paste and liquid foods as well, associated with weight loss (12Kg). Six months later he showed progressive increase of submentalis region volume, with softened consistency associated with macroglossia and difficulty to protrude the tongue. He presented as underlying disease only systemic arterial hypertension that was under clinical control with daily use of PO diuretics. His brother had died of consequences of tongue cancer. The physical examination showed submentalis mass extending to the bilateral submandibular regions, of softened consistence, mobile during swallowing, associated with diffuse increase of the tongue (macroglossia), with no other color or nodular lesion associated (Figures 1 and 2). Diagnostic hypotheses were tongue malignant tumor, amyloid accumulation disease, localized vascular disease or systemic disease such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency. The patient was treated with corticoids and pentoxyphilline and there was no reduction of tongue volume or submentalis/submandibular mass. Laboratory tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL) and abnormal renal function (urea: 103 mg/100ml, Creatinin:1.7 mg/100ml). Serology for hepatitis B and C were negative. Protein electrophoresis showed increase in gamma globulin (total Proteins: 5.8 g%, albumin: 2.8 g%; 1 globulin: 0.3 g%, 2 globulin: 0.6 g%, globulin: 0.6 g% and gamma globulin: 1.5 g%). 24-hour proteinuria was 0.48 g/l - 816 mg/24h, with urine culture and renal ultrasound without abnormalities. Electrocardiogram showed anterior-superior left division blockage, septal inactive zone, left ventricular overload, and affections to anterior ventricular repolarization. Neck Computed Tomography (CT scan) showed significant and symmetrical increase of the tongue especially in the posterior region, with no focal lesions, taking to lower displacement of all structures below the tongue (Figure 3). These findings were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck (Figure 4). No vascular affections were identified. Vitamin B12 values (192.0 pg/mL), folic acid (2.7 ng/mL) and blood TSH were within the normal range. We conducted tongue biopsy and the findings were pinkish substances, distributed among muscle fragments, suggestive of amyloid substances (Figure 5). He presented birefringence under polarized light microscopic visualization when stained with Congo red (Figure 6). We performed abdominal fat aspirate, which showed presented of amyloid substances, which confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. Finally, the patient was submitted to myelogram and there were no indications of MM.

DISCUSSIONOral manifestations of amyloidosis were described in 39% of the cases of this disease 6. Amyloid deposits on the tongue of patients with MM are frequent and may lead to macroglossia (increase in tongue volume) 6, 7, which is the most frequent oral finding in these cases. The first signal of primary amyloidosis may be increased tongue volume 8. Tongue color may be pale and, occasionally, reddish 9.

The main finding in the physical examination of our patient was macroglossia. The submandibular mass found was in fact the result of the exuberant macroglossia, probably leading to swallowing difficulties.

The diagnosis of amyloidosis should not be the first one to be considered when in view of a case of macroglossia. Other diseases, such as tongue malignant tumor, vascular diseases or systemic etiology such as hypothyroidism or vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency should always be investigated. In fact, some diseases may occur more frequently than amyloidosis, but a 71-year-old patient coincides with the epidemiological pattern for amyloidosis. Weigh loss and presence of submandibular mass could have been caused by malignant disease, but it was excluded based on CT scan and MRI findings. Finally, tongue biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of amyloidosis and abdominal fat aspirate showed that it was systemic amyloidosis. Systemic etiologies such as folic acid, vitamin B12 deficiency or hypothyroidism were excluded based on the normal results of laboratory tests.

In 1935, Kramer and Som APUD 3, in a literature review, identified 95 cases of amyloid deposits in the upper aerodigestive and lower respiratory tracts, and larynx was affected in 36 patients, tongue in 16 patients, larynx and tongue in 8 patients, trachea in 13 patients, tracheobronchial tree in 4 patients, nose in 6 patients, and there were few cases of oral, pharynx and lung affections.

Kerner et al.1 observed that tongue and larynx were the preferred sites for head and neck amyloidosis, finding 59% of patients with tongue amyloidosis and associated MM.

Tongue biopsy leads to diagnosis of amyloidosis, but it does not define its subtype and the systemic or localized form, which is important information for survival 1. Localized form, which is extremely rare 3, has better prognosis than the systemic form.

The differential diagnosis between the systemic and localized form of amyloidosis may be made through abdominal fat aspirate or rectal biopsy 10.

In the studied patient, we preferred to perform abdominal fat aspirate rather than rectal biopsy because it is a simpler procedure, consisting of removal of fatty tissue from the anterior wall of the abdomen through fine needle aspiration 10. These two procedures were positive in 75% to 90% of the patients with systemic amyloidosis 1. As shown, amyloid substance in the abdominal fat aspirate led to the conclusion that it was systemic amyloidosis.

Amyloid deposits have some characteristics: they are eosinophilic in hematoxylin-eosin staining and present birefringence under polarized microscopic light when stained in Congo red. This is the simplest and most accepted criterion for diagnosis of amyloidosis 11. Under electron microscopy, these proteins have fibrous appearance 12.

After the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis, it is important to know its characteristics: whether it is primary or secondary and also if it is associated with multiple myeloma. There is considerable difference in survival of patients with systemic or localized amyloidosis 1,with or without MM. In Mayo Clinic, it was observed that the mean survival was 15 months in patients with amyloidosis without MM and 5 months in cases associated with MM APUD 1.

Secondary amyloidosis was excluded since the patient did not present any chronic disease such as tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn's disease.

More than half of the cases of systemic amyloidosis are associated with MM, but only 6 to 15% of the cases of MM have associated amyloidosis 13.

Kyle and Bayrd APUD 1 reported incidence of 26% of macroglossia by amyloidosis in patients with MM.

Reinish et al.9 reported 54 cases of oral amyloidosis in patients with MM. Tongue was affected in all of the patients with oral amyloidosis. In most cases, pain was the main symptom, followed by dysphagia and speech difficulties.

Xerostomia is a result of amyloid deposits in the tongue and salivary glands, and it may be the cause of dysphagia 7.

Even though protein electrophoresis showed increase in gamma globulin, which could have indicated MM, myelogram was normal and excluded this disease.

Renal disease is the main cause of death among patients with amyloidosis APUD 1 and the patient in our case report already showed some signals of cardiac and renal involvement.

In the literature, surgical reduction of the tongue is suggested when there is macroglossia 5. Kerner et al.1 treated some of their patients with macroglossia resulting from amyloidosis with glossectomy, with proper scarring and improvement in quality of life, since speech and feeding skills were restored. Dendy et al.14 presented a case of a 62-year-old female subject with macroglossia resulting from primary amyloidosis submitted to resection of two anterior thirds of the tongue, with very satisfactory results. According to Reinish et al.9, since tongue lesions frequently recur, requiring successive resections, surgical intervention should be considered only for extreme cases of macroglossia that may take to airway obstruction.

We decided not to conduct any surgical procedure in our patient since the literature has no consensus about quality of life improvement and because of high morbidity of the patient. He is currently being followed up by the medical team with wait and see approach.

CONCLUSIONEven though amyloidosis is not the main diagnostic hypothesis that should be considered when facing a patient with macroglossia, this disease should not be forgotten, given that clinical support is essential to control the possible associated diseases, such as renal or cardiac failure and MM.

Moreover, more studies are required to define the possible benefits and consequences of surgical procedures used to treat macroglossia.

REFERENCES1. Kerner MM, Wang MB, Angier G, Calcaterra TC, Ward PH. Amyloidosis of the Head and Neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121:778-82.

2. Wong CK, Wang WJ. Systemic Amyloidosis. A Report of 19 Cases. Dermatology 1994; 189:47-51.

3. Simpson GT, Strong MS, Skinner M et al. Localized amyloidosis of the head and neck and upper aerodigestive and lower respiratory tracts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1984; 93:374-9.

4. Pizov G, Soffer D. Amyloid tumor (amyloidoma) of a peripheral nerve. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1986; 110:969-70.

5. Westermark P, Stenkvist B. A new method for the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1973; 182:522-3.

6. Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Kurtin PJ et al. Laryngeal amyloidosis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992; 106:372-7.

7. Reinish EI, Raviv M, Srolovitz H, Gornitsky M. Tongue, primary amyloidosis, and multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77:121-5.

8. Babajews A. Occult multiple myeloma associated with amyloidosis of the tongue. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1985;23:298.

9. O'Doherty DP, Neoptolemos JP, Bouch DC, Wood KF. Surgical complications of amyloid disease. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:281.

10. Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Amyloidosis (AL) clinical and laboratory features in 229 cases. Mayo Clin Proc 1983; 58:665.

11. Raubenheimer EJ, Dauth J, de Coning JP. Multiple myeloma presenting with extensive oral and perioral amyloidosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986; 61:492.

12. Hawkins PN, Lavender JP, Pepys MB. Evaluation of systemic amyloidosis by scintigraphy with 123I-labeled serum amyloid P component. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:508-13.

13. Franklin EL, Gorevic PD. The amyloid diseases. In: Fougereau, M & Dausett J (eds.) Immunology 80. Progress in Immunology IV. London: Academic Press; 1980. p. 1219-30.

14. Dendy RA, Davies JR, Gorst DW. A tongue resection in macroglossia due to primary amyloidosis. 1989; 27: 329-33.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Note macroglossia; it was associated with submentalis/submandibular mass, with no color changes or nodular lesions on the tongue.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. When the patient opened his mouth, it was possible to see marked macroglossia.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Axial section CT scan of the neck with soft part windows showing macroglossia, especially on the posterior region (arrow), with no nodule lesions.

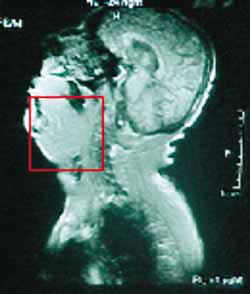

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Sagittal section of MRI showing macroglossia that led to inferior displacement of structures localized under the tongue.

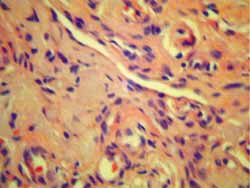

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Biopsy of the tongue stained with hematoxylin-eosin: pink substance distributed between muscle fragments suggesting amyloid substances.

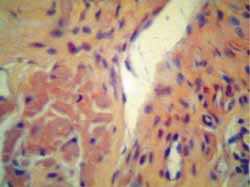

Figure 6.

Figure 6. Tongue biopsy stained in Congo red: birefringence under polarized light microscopic view.