INTRODUCTIONEncephalic abscesses, located in the brain and the cerebellum, and empymeas are rare infectious neurological diseases whose initial clinical manifestation can be simply headache. In a late phase, it can lead to death of individual by transtentorial herniation caused by intracranial hypertension or sepsis.

Early diagnosis, as well as etiology and location, are essential for the appropriate therapy. For early diagnosis, the physician must have in mind the possibility of such a neurological complication when facing infectious manifestations that apparently seem to be common, such as otitis and sinusitis, before the classical signals of intracranial hypertension. ENT diseases have long been considered the most common causes of cerebral abscess. In the literature, we found reports of otogenic foci in 30% to 40%1, 2, 3 and sinusal foci in 11%4 of the cases.

Despite the fact that advance in antibiotic therapy and imaging methods (computed tomography and magnetic nuclear resonance) have supported significantly early diagnosis and treatment, encephalic abscesses still present high mortality rates (up to 18.4%) and neurological sequelae5.

Many neurosurgical approaches have been proposed in the treatment of cerebral abscesses. However, as shown by the literature6, 7, 8,, only the approach of the abscess, with no elimination of the primary focus, is not the ideal intervention, because it predisposes to high rates of recurrence, since the primary infectious focus will continue to feedback the abscess area. Thus, it is important to first approach the primary focus - usually surgically, in an attempt to control it.

The purpose of the present study was to demonstrate the high incidence of Otorhinolaryngology diseases in cases of cerebral abscesses and empyemas, requiring specific ENT treatment for the control of the primary infectious focus.

MATERIAL AND METHODWe conducted a retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed with cerebral abscess and/or empyema and hospitalized at Hospital São Paulo – UNIFESP/EPM between 1987 and 2000, carried out in two steps. In the first step, we identified the hospitalized patients that had been admitted into the hospital from the emergency room of Otorhinolaryngology with diagnosis of cerebral abscess and empyema (infectious intracranial complication - IIC) resulting from otorhinolaryngological disease. In the second step, we identified patients with cerebral abscess and empyema (infectious intracranial complications) submitted to neurosurgical procedures (trepanation, craniotomy or stereotaxic surgery) at the operating room of the institution. After we identified the cases that were included in both lists, we analyzed the medical files tying to collect data about age, gender, underlying etiology, IIC, culture, antibiotic therapy used, ENT and neurosurgical procedures performed during hospitalization, length of stay, final sequelae and other relevant observations.

We gathered data on 67 patients with subdural abscess or empyema selected according to the methodology described above. Out of the total, 40 (59.7%) were related to ENT pathologies, whereas 27 (40.3%) were related to other etiologies.

RESULTSTable 1 synthesizes the etiologies found in 67 patients included in the study. Table 2 analyzes the patients with IIC and otorhinolaryngological etiology. In Tables 3 and 4 we present data about patients with otitis and sinusitis (which amounted to 90% of the otorhinolaryngological etiologies) concerning age and gender. In Tables 5 and 6 we analyze only the cases of otitis, sinusitis and non-otorhinolaryngological pathologies concerning type and site of IIC, results from the culture and antibiotic used. Finally, Tables 7 and 8 try to sum up the data of patients with otitis and sinusitis and surgical procedures performed (otorhinolaryngological and neurosurgical), sequelae and mortality.

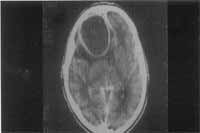

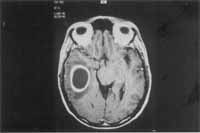

We also show some examples of illustrations: Figure 1 - frontal abscess as a complication of sinusitis (CT scan axial section); Figure 2 - cerebellar abscess as a complication of otitis (CT scan axial section); Figure 3 - temporal abscess as a complication of otitis (MRI axial section); Figure 4 - temporal abscess as a complication of otitis (MRI coronal section).

Table 1. Summary by etiology of intracranial complications.

All cases: 67 (100%)

• Otorhinolaryngological etiology: 40 (59.7%)

- Otitis: 25: (37.3%)

- Sinusitis: 11 (16.4%)

- Other ENT etiologies: 4 (6%)

• Non-ENT etiology: 27 (40.3%)

- Postoperative craniotomy: 8 (11.94%)

- Head trauma: 7 (10.4%)

- Ventricular shunt to hydrocephalus: 3 (4.5%)

- Heart disease: 3 (4.5%) Congenital: 2 / Endocarditis: 1

- Other infections: 3 (4.5%)

- Hydradenitis 1 (1.5%)

- Idiopathic: 2 (3%)

Table 2. Otorhinolaryngological Diseases - ETIOLOGY

All cases: 40 (100%)

• Otitis: 25 (62.5%)

- Cholesteatomatous otitis media: 20 (80%)

- Acute Otitis media: 5 (20%)

• Sinusitis: 11 (27.5%)

- Chronic Sinusitis: 7 (63.6%)

- Acute Sinusitis: 4 (36.4%)

• Tonsillitis: 2 (5%)

• Paranasal sinuses carcinoma: 1 (2.5%)

• Periodontal abscess: 1 (2.5%)

Table 3. Otitis and Sinusitis – Gender

• Otitis: 25 cases

- 11 female (44%)

- 14 male (56%)

• Sinusitis: 11 cases

- 1 female (9%)

- 10 male (91%)

Table 4. Otitis and Sinusitis – AGE (mean and variation)

• Otitis: 25.8 years (0.5 – 71 y)

- Cholesteatomatous otitis media: 27.4 years (09 – 66 y)

- Acute Otitis media: 19.7 years (0.5 – 71 y) *

* 6.8 years (if we exclude one 71 year-old patient)

• Sinusitis: 18.1 years (9 – 37 y)

- Chronic sinusitis: 21.6 years (14 – 37y)

- Acute Sinusitis: 12 years (9 – 15 y)

Table 5. Otitis, Sinusitis and Non-Otorhinolaryngological

INTRACRANIAL COMPLICATION (type and site)

• Otitis: 25 cases

- Abscesses: 25

- Cerebellar: 6 (24%)

- Temporal: 12 (48%)

- Temporal/parietal: 6 (24%)

- Temporal/frontal: 1 (4%)

- Empyema: 1 (associated with abscess)

• Sinusitis: 11 cases

- Abscesses: 8 Frontal: 5 (62.5%)

- Frontal/parietal: 2 (25%)

- Temporal/parietal: 1 (12.5%)

- Empyema: 3

• Non-otorhinolaryngological: 27

- Abscesses: 26 Parietal 9 (34.6%)

- Frontal: 7 (26.9%)

- Occipital: 2 (7.7%)

- Temporal/parietal: 2 (7.7%)

- Temporal/occipital: 1 (3.8%)

- Frontal/parietal: 1 (3.8%)

- No report of localization: 4 (15.4%)

- Empyemas: 2 * 1 associated with abscess

Table 6. Otitis, Sinusitis and Non-Otorhinolaryngological

CULTURES and PRIMARY ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

• Otitis: 25 cases – ceftriaxone + metronidazole

- Sterile: 14 (56%)

- P. mirabilis: 5 (20%)

- Enterococcus: 1 (4%)

- P. aeruginosa: 1 (4%)

- Pneumococcus: 1 (4%)

- H. influenza: 1 (4%)

- No culture: 2 (8%)

• Sinusitis 11 cases – ceftriaxone + metronidazole + vancomycin

- Sterile: 6 (54%)

- S. aureus: 3 (27,3%)

- S. viridans: 2 (18,2%)

- Enterococcus: 1 (9%) associated with S. aureus

• Non-Otorhinolaryngological

- S. aureus: 3

- Enterococcus: 1

- Criptococcus: 1

- Nocardia: 1

- Actinomices: 1

- Enterobacter: 1

- Aspergilus: 1

- Gram negative bacilli: 1

- BAAR: 1

Table 7. Otitis and Sinusitis – SURGICAL PROCEDURES

(Otorhinolaryngological and Non-Otorhinolaryngological)

• Otitis: 25 cases

- Otorhinolaryngological Procedures:

Yes: 19 (76%)

Radical Mastoidectomy: 17

Simple Mastoidectomy: 02 *

*1 AOM and 1 congenital cholesteatoma

No: 6 (24%) * 4 AOM and 2 deaths

- Neurosurgical Procedures:

Yes: 19 (76%) * 2 needed new approach

No: 6 (24%)

• Sinusitis: 11 cases

- Otorhinolaryngological Procedures:

Yes: 2 (18.2%)

No: 9 (81.8%)

- Neurosurgical Procedures:

Yes: 7 (63.6%) * 1 needed new approach

No: 4 (36.4%)

Table 8. Otitis and Sinusitis – SEQUELAE AND MORTALITY

• Otitis: 25 cases

- Sequelae: 7 (28%) Paresis VI pair: 3

- Dysmetria: 2

- Hemyparesis: 2

- Paresis VII pair: 1

- Dysarthria: 1

- Deaths: 3 (12%)

• Sinusitis: 11 cases

- Sequelae: 2 (18.2%) Seizures: 2

- Deaths: 2 (18.2%) *1 by concomitant leukemia

DISCUSSIONThe methodology employed in the present study - retrospective analysis of medical Tables - presented advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage is that it enabled us to gather a long list of patients with cerebral abscesses and empyemas (intracranial complications - IIC) from otorhinolaryngological etiology, events that are not very frequent in daily clinical practice, but which were significant in the 12-year experience of a reference center (40 cases). Since it was not a study that followed a protocol, useful information was lost throughout the service, and could not be considered. The purpose of describing a group of IIC from other etiologies than otorhinolaryngological was to define the role of otorhinolaryngological etiologies in the total. However, for operational reasons, we only listed those that had been submitted to surgery (since other specialists conducted treatment) and for this reason we could only infer the approximate number. Regardless of that, we could highlight the great importance of otorhinolaryngological diseases (approximately 60% of the cases) in the genesis of IIC, a fact confirmed by other authors2.

We noticed that in the group of patients with otorhinolaryngological diseases, otitis episodes were the main cause of IIC (62.5%), followed by sinusitis (27.5%) and other less expressive diseases (10% of the total). Considering only otitis, the group was in general formed of young subjects (3rd and 4th decades) with balance between the genders, slight predominance of male gender (56%), in accordance with the world literature4. Cholesteatomatous otitis (COM) was the most prevalent one with 80% of the cases and the other 20% were cases of acute otitis media (AOM), which affected younger patients. Thus, in accordance with the international literature, children have a greater risk of IIC during an episode of AOM, whereas COM was the most prevalent one1. In the group of sinusitis, in addition to the young age of patients, we could notice a clear predominance of male subjects (90%), which was also in accordance with the world literature5, 9, 10. We also noticed an balance between chronic (CS) and acute (AS) cases that there were, respectively, 63.6% and 36.4%, a fact inverted to what is seen in the world literature2, 9, which reported an incidence of 75% of acute cases. The other ENT pathologies were not very frequent (1 or 2 subjects in each pathology), which prevented us from making any further analysis.

We noticed that encephalic abscess was the most common IIC associated with otorhinolaryngological diseases with the presence, associated or not, of 4 cases of subdural empyema. The world literature is still uncertain whether the most frequent IIC would be encephalic abscess or meningitis2, 4, 9, 11, but we should bear in mind that cases of meningitis are sometimes not diagnosed because of the risk of herniation of the CSF puncture in patients with intracranial hypertension caused by the abscess9. As to location of abscess, we pointed out that most of them were close to the primary focus, predominantly frontal in sinusitis and temporal or cerebellar in otitis. This fact can be explained by the dissemination routes of infectious agents, which takes place through the venous system that interconnects the paranasal sinuses and the middle ear with the adjacent meninx, or by direct extension of bone erosion, fissures (congenital or acquired) and preexisting foramens1, 2.

As to patients with otorhinolaryngological diseases, the results of cultures showed a great number of negative cultures (over 50% of sterile results in both groups), even though we should refer to the fact that most patients had already started antibiotic therapy when the cultures were processed. In addition, we should assume that the material collected is not always properly handled (duration of processing, anaerobic means of culture are hardly available, etc.) and it can also influence this high rate of negative results. Despite that, culture should never be dispensed. The international literature provides that most IIC present a mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora without one prevalent germ, which indicates the use of wide spectrum primary antibiotic therapy, such as the association of ceftriaxone, metronidazole and vancomycin, later directed based on the culture results2, 10, 12.

Figure 1. Frontal abscess as a complication of sinusitis (CT scan axial section)

Figure 2. Cerebellar abscess as a complication of otitis (CT scan axial section)

Figure 3. Temporal abscess as a complication of otitis (MRI axial section)

Figure 4. Temporal abscess as a complication of otitis (MRI coronal section)

Most authors defend that in addition to antibiotic therapy we should solve the primary focus and drain the IIC as much as necessary2, 9. In our study, we noticed that most cases of otitis underwent otorhinolaryngological surgical intervention at the same hospitalization period (76%), except for cases of AOM (4) and those that progressed to death in short time and did not present clinical conditions to be submitted to a surgical procedure (2). The preferred otological surgery was radical mastoidectomy (17 out of 19) since they were cases of COM with IIC, and there were 2 conservative mastoidectomy surgeries (1 congenital cholesteatoma and 1 AOM). Sinusitis cases were treated initially with less aggressiveness and only 2 cases underwent surgical procedures (18.2%), which may be a result of greater number of acute processes. However, this conservative attitude has been reconsidered by us based on the literature that defends surgical drainage of the primary focus as a way to reduce length of hospital stay2, 5, 9, 10. In patients with otitis there were procedures of neurosurgical drainage (trepanation, craniotomy and stereotaxic puncture) in 76% of the cases, in 2 they did not succeed and had to be repeated. A similar percentage of patients with sinusitis underwent neurosurgical intervention (63.3%) and there was only one case of initial failure.

The rate of sequels was similar in the patients with otitis and sinusitis (28% and 18%, respectively) and related to the IIC site, similar to the reports in the literature, which range from 25 to 40%2, 3, 9. Mortality reached 12% of the cases of otitis (1 AOM and 2 COM), similar also to the group with sinusitis (18%), being that in the latter 1 case was resultant from the fact that the patient had acute M2 myeloid leukemia non-responsive to chemotherapy treatment.

CONCLUSION1. Infectious otorhinolaryngological diseases were responsible for a large number of cerebral abscess and empyema cases hospitalized in our center.

2. Most of the otorhinolaryngological cases with abscess and empyema were young subjects.

3. There was a tendency towards more male cases in the ENT group of abscesses, slightly in the otitis group and very evident in the sinusitis group.

4. The location of the abscess is 76% of the times was in the temporal lobe when the abscess was otogenic and 24% of the times, in the cerebellum. When it was sinusal, it was 87.5% of the times in the frontal lobe. It showed closeness between primary infectious focus and installation site of the encephalic abscess.

5. The preferred antibiotic therapy should be initially wide and directed later by the cultures, which should never be dispensed.

6. The resolution of the primary ENT focus should be conducted, either clinically and/or surgically, and in most cases it is preferably surgical.

REFERENCES 1. Ayyagari A, Pancholi VK, Kak UK, Kumar N, Khosla VK, Argawal KC, Gulati DR. Bacteriological spectrum of brain abscess with special reference to anaerobic bacteria. Indian J Med Res 1983;77:182-6.

2. Cawthorne T. Discussion on diagnosis and treatment of cerebral abscess. Proc R Soc Med 1945;38:438-40.

3. Garfield J. Management of supratentoreal intracranial abscess: a review of 200 cases. Br Med J 1969;2:2-11.

4. Clayman GL, Adanms GL, Paugh DR, Koopmann JR CF. Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institucional review- Laryngoscope 1991;101:234-9.

5. Kangsanarak J, Navacharoen N, Fooanant S, Ruckphaopunt K. Intacranial Complications of Suppurative Otitis Media: 13 years’ experience. Am J Otolaringol 1995;16(1):104-109.

6. Penido NO. Abscesso encefálico otogênico: tratamento e evolução. Tese de Mestrado, Escola Paulista de Medicina. São Paulo, 1992.

7. Penido NO, Borin A, Pedroso JES, Pessuto JMS. Complicações Intracranianas Sinusais. Rev Bras de Otorrinol 2001;67(1): 36-41.

8. Penido NO, Mota PH, Mascari DAS, FukudaY. Abscesso cerebral de origem otogênica. Relato de um caso. Acta Awho 1990;9: 32-5.

9. Ballenger JJ. Complicaciones de la otitis. In: Enfermidades de la nariz, garganta, oido, cabeza y cuello. 3a ed. Barcelona: Salvate; 1988. p. 1141-66.

10. Habib RG, Girgis NI, Abu El Ella AH, Farid Z, Woody Y. The treatment and outcome of intracranial infections of otogenic origin. J Trop Med Hug 1988;91:83-6.

11. Jones RL, Violaris NS, Chavda SV, Pahor AL. Intracranial complications of sinusitis: the need for agressive management. J Laryngol Otol 1995;109:1061-2.

12. Giannoni CM, Stewart MG, Alford EL. Intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1997;107:863-7.

13. Kangsanarak J, Fooanant S, Ruckphaopunt K, Navacharoen N, Teotrakul S. Extracranial and intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media. Report of 102 cases. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:999-1004.

14. Lerner DN, Choi SS, Zalzal GH, Johson DL. Intracranial complications of sinusitis in childhood. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1995;104:288-93.

15. Quijano M, Schuknecht HF, Otte J. Temporal bone pathology associated with intracranial abscess. ORL 1988;50:2-31.

16. Rosenfeld EA, Rowley AH. Infections intracranial complications of sinusitis, other than meningitidis, in children: 12-year review. Clin Infec Dis 1994;18:750-4.

1 Ph.D. in Medicine, UNIFESP/EPM.

2 Master in Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP/EPM.

3 Full Professor, Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, UNIFESP/EPM.

Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Federal University of São Paulo / Escola Paulista de Medicina.

Address correspondence to: Dra Norma Penido

Rua Rene Zanlutti, 160, ap 131 Chácara Klabin São Paulo – SP 04116-260

Tel. (55 11) 5573.1388 – Fax: (55 11) 3141.9878

Study presented at the II Congresso Triologico de Otorrinolaringologia da SBORL – Goiania, Brazil, 2001.

Article submitted on August 12, 2002. Article accepted on September 12, 2002