INTRODUCTIONThe introduction of functional endoscopic sinuses surgery has renewed the interest in rhinosinusal surgery. Despite the principle that says that the surgical procedure should be oriented to the opening of the ostia, in order to restore natural mucociliary clearance, many issues related to the pathophysiology of rhinosinusitis remain unanswered7, leading to different researches in this field.

Stammberger in 1986, proposed that the obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex (OMC), regardless of anatomical configuration or hypertrophied mucosa, could cause block and stagnation of secretions, becoming infected or perpetuating the infection18. These affirmations are based on studies that showed the direction of the ciliary transport to the natural ostium18.

However, there is no appropriate controlled investigation to demonstrate that the surgical application of these affirmations would lead to better results concerning conventional surgery. One significant point to be considered is whether the presence of anatomical variations, causing obstruction of OMC, are more prevalent in the symptomatic group with confirmed disease than in the control group.

The paucity of studies in this area is really amazing. Some do not differentiate symptomatic from asymptomatic groups11. Few comparative studies have been carried out and they have not shown consistent association between anatomical variation that may cause OMC obstruction and rhinosinusitis13,21.

One of the key problems in the test to validate the surgical technique, based on Stammberger's proposal18, is that rhinosinusitis is not a condition, not even a spectrum of manifestations of the condition, but rather a conjunction of several pathological processes. The purpose of the present study was to compare the presence of various anatomical variations associated with OMC in patients with and without chronic rhinosinusitis, evaluating the importance of these variations in the genesis of the chronic inflammation of the paranasal sinuses.

MATERIAL AND METHODThe studied sample consisted of patients submitted to computed tomography scan (CT scan) between January 1993 and July 1998. We analyzed 200 CT scans of patients who did not have primary or acquired immunosuppression, transplantation of any organ, or severe congenital malformations9. The CT scans followed the technical protocol of the Service of Radiology for orbit exams, with overlapped sections of 3 or 5 mm, or 2-3 mm sections in the paranasal sinuses protocol, with recordings at the axial and coronal sections and intravenous contrast, if not contraindicatedl6. The CT scans were performed with two devices: Philips model Tomoscan LX/C, matrix 512 x 512 and General Electric, model CT MAX, matrix 320 x 320. The tests were selected based on the following division: in the first group, we analyzed the CT scans of patients who had orbital disease. In this first stage, we selected 100 CT scans of patients who had no complaints of chronic nasosinusal disorder (information collected through medical files of patients). Orbital CT scan was chosen because nasal and paranasal structures are evidenced in them and it is easy to identify variations. Therefore, the first analyzed group comprised patients who could have anatomical variations of OMC, but without any kind of nasal and/or sinusal pathology. The second group of studied patients was selected from 100 paranasal sinuses CT scans with patients who had chronic rhinosinusitis confirmed by clinical history and endoscopic examination, reported in the medical file filled in at the Ambulatory of Rhinosinusology. Therefore, we had two main arms: the first one (group 1) comprised 100 CT scans with and without abnormalities of OMC, but with no chronic rhinosinusitis; and the second group (group 2) comprised 100 CT scans with or without OMC abnormalities but with confirmed chronic rhinosinusitis. We conducted axial and coronal sections in both groups20. The study included data concerning: (1) gender, (2) age range in intervals - 0-10 up to 81-90; the youngest patient was 8 years of age, whereas the oldest was 81 years, and (3) OMC variations.

RESULTSAfter the analysis of the CT scans, we accounted the results according to the groups. The 100 CT scans from group 1, without rhinosinusitis, but with of without anatomical variations, belonged to 38 men and 62 women. The distribution by age range fell within 30 and 40 years. In this group, the distribution of patients was 49% normal patients with variation and 51 % normal patients without OMC variation.

Each alteration was counted only once if bilateral, and it was associated if contra or ipsilateral. The most common variations for patients in group 1 are listed in Table 1. There were also multiple findings, as shown in Table 2. Figures 1-5 represent some of the anatomical variations found in group 1.

As to group 2, gender distribution was 45 % women and 55% men. Age range was 30-55 years. In the 100 paranasal sinuses CT scans of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis we noticed the presence of 52% of patients with diseases and variations and 48% of patients with chronic condition but no OMC variation. Distribution of variations is shown in Table 1. This group also had multiple findings, as shown in Table 2. Figures 6-8 show some of the findings for group 2.

TABLE 1 - Percentage of anatomical variation of OMC and its distribution in groups 1 and 2.

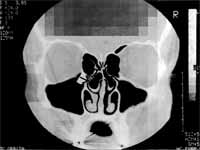

Figure 1. Bilateral bullous concha and normal paranasal sinuses in group 1 patients. Coronal section.

Figure 2. Hyper aired Agger nasi and normal paranasal sinuses in group 1 patients. Coronal section.

Figure 3. Haller's cell on the left and normal paranasal sinuses in group 1 patients. Coronal section.

Figure 4. Bilateral bullous concha and hyper pneumatized ethmoidal bulla on the right, with normal paranasal sinuses in group 1 patients. Coronal section.

Figure 5. Presence of bullous concha with velamentum of its interior and normal paranasal sinuses in group 1 patients. Coronal section.

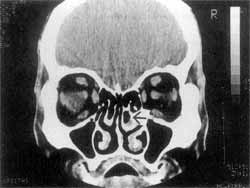

Figure 6. Right bullous concha with maxillary and fronto-ethmoidal velamentum in group 2 patients. Coronal section.

TABLE 2 - Percentage distribution of multiple findings of anatomical variations found in groups 1 and 2.

The main differences concerning presence of chronic rhinosinusitis or not were bulky middle concha and agger nasi hyper aeration. Respectively, the variation bulky middle concha was most frequently found with rhinosinusitis, presenting statistically significant difference (Chi-square = 3.36; p = 0.05) between the group with rhinosinusitis and the group without rhinosinusitis. The anatomical variation agger nasi hyper aeration presented statistically significant difference when comparing the group without rhinosinusitis and the group with rhinosinusitis (chi-square = 5.50; p = 0.01). The remaining variations were equally distributed among the two groups, because paradoxical curvature of the middle concha and hyper pneumatized ethmoidal bulla presented the same number of variations in the two groups (no statistically significant difference for both variations according to Fischer's exact test = 0.99). Bullous concha had variation of 1% between groups (group 1 found 19% of the CT scans with bullous concha and group 2 had the variation present in 20% of the cases), with no statistically significant difference (Chi-square = 0.01, p=0.99). The presence of Haller's cells had a 3% difference between the groups (12 % in group 1 and 9 % in group 2), but there was no statistically significant difference (Chi-square = 0.21; p = 0.64).

Figure 7. Paradoxical curve of middle concha and maxillary and ethmoidal velamentum in group 2 patients. Coronal section.

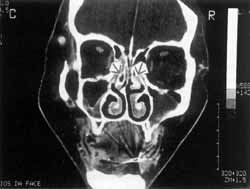

Figure 8. Paradoxical curve of right middle concha and left bullous concha with maxillary-ethmoidal velamentum in group 2 patients. Coronal section.

Table 2 shows the percentage distribution of multiple findings of anatomical variations found in groups 1 and 2, which were statistically similar.

DISCUSSIONChronic rhinosinusitis may be predisposed by different factors, and an anatomical variation of OMC is one of them. The question being answered here is whether this hypothesis is essential for the genesis of the chronic disease or if it is only one further factor. To come up with an answer, we analyzed the CT scans (200) of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and patients without the pathology (orbital CT scans ordered because of ophthalmic conditions). The results of this study revealed presence of anatomical variations in nearly half of the tests. Patients with history of chronic rhinosinusitis could present obstruction of OMC as a triggering factor of the disease. Nasal mucosa conditions (allergic rhinitis and others)14 and deficiency in clearance of secretion, are conditions accepted to explain the chronic sinusal process3. Variations of OMC, which obstruct the air passage in the ostiomeatal area, are found in different sizes and shapes.

In our study, bullous concha was the main variation of OMC: 20% of the 200 CT scans presented it. Among them, chronic rhinosinusitis and concha bullous was found in 10% of the 200 cases, data- similar to those reported by Bolger et al.2 and Jones et al.7. Therefore, we may infer that such anatomical variation requires a patient-to-patient analysis in order to be identified as pathophysiological basis, because neither our study nor the ones reported here presented statistically significant differences.

Projection of infraorbital ethmoidal cell, Haller's cell, may have clinical significance because it causes recurrent maxillary rhinosinusitis. Studies demonstrated variable frequency of alterations, showing rates of 20%2 to 34%17. These high rates may represent higher sensitivity of the test and it is an excellent CT scan technique, accounting for the detection of small and delicate structures. In our sample, findings were equivalent to 10 % of the cases and only 4% simultaneously had chronic rhinosinusitis, as opposed to 3% found by Jones et al.7.

Hyper pneumatized ethmoidal bulla is a rare variation, but it had not been properly studied for a long time4. This varied form of ethmoidal bulla may be found unilateral or bilaterally, at rates ranging from 2.5 %2 to 12%4. In our sample of 200 CT scans, we reached a percentage of 4% (eight cases, four of them - 2 % - with chronic rhinosinusitis and four of them - 2 % - without chronic rhinosinusitis, as opposed to 5 % reported by Jones).

The most anterior cell of ethmoid - agger nasi, if presented hyper aired may be a triggering factor for obstruction of ethmoid-frontal recess and originate chronic rhinosinusitis1z, especially the frontal type. We found a total of 8% (16 cases) of patients with this kind of CT scan finding and only 1.5 % (or three cases) developed chronic disease, that is, the proportion of cases with agger nasi hyper aeration and chronic rhinosinusitis was smaller than the group without rhinosinusitis; as a result, this variation may be considered not preponderant in the genesis of chronic rhinosinusitis, since the literature reports a 10% variation.

Bulky middle concha, without pneumatization, was considered a possible agent of chronic rhinosinusitis, as well as variation from normal range. We excluded pneumatization of middle concha (either small or large). We noticed that the alteration was present in 14% (or 28 cases). Among the 28 CT scans of patients who had middle concha hypertrophy, chronic rhinosinusitis was found in 67% of the patients. Some authors found in their studies 47%10 to 52%5 of bulky middle concha in patients with rhinosinusitis15,16. The statistical analysis of our study showed that the presence of bulky middle concha was statistically greater in the group with chronic rhinosinusitis. Although many authors report that bulky middle concha is a anatomical variation, it is important to point out that chronic rhinosinusitis itself may be a factor that stimulates the concha mucosa, which would explain the incidence obtained in group 2 of our study.

The presence of paradoxical curvature of middle turbinate as a causal factor of OMC obstruction, and therefore, the cause of chronic rhinosinusitis, was also evaluated. We detected this finding in 2 % of the cases (four patients), two of them without rhinosinusitis and two with rhinosinusitis. It is suggested that it is not a very frequent variation, but if present, it may induce chronic rhinosinusitis (50% of the CT scans with paradoxical curvature of middle turbinate showed chronic rhinosinusitis). There were findings of 11% and 12%, half of them causing chronic rhinosinusitis7,9.

The findings were recorded as single (unilateral or bilaterally) or multiple. We detected 14 cases of multiple findings, and bullous concha was the most frequently associated alteration. The presence of a miscellaneous of variations does not necessarily predispose to chronic rhinosinusitis, because in 57% of the cases there was no chronic condition.

It is believed that the intrinsic disease of nasal and paranasal mucosa, interfering at the level of clearance, could be a more important factor for the genesis of chronic rhinosinusitis than anatomical variations of OMC7. Our study confirmed this thought. These results seem to disagree with the hypothesis of Stammberger18, which related narrowing of OMC as an etiological factor for the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis15,19.

However, this study was concentrated mainly on the radiological bone structure and not on the presence or absence of any contact mucosa in the ostiomeatal area. It is likely that mucosal edema and obstruction are important in the pathogenesis of rhinosinusitis, especially in cases in which the disease persists. Based on these data, we suggest that paranasal sinuses CT scan becomes an integral part of the investigation tools employed in cases of chronic sinusal pathology, because it is the method that better presents evidence of OMC, supporting the surgical procedure in the region8.

Counting on good clinical history, physical examination and CT scan, diagnostic and surgical management will be more precise and the objectives will be met1. Intra and post-operative analyses among radiologists confirm the previous CT scan findings, increasing the use of CT scan concerning variation of OMC.

The results obtained here revealed that chronic rhinosinusitis is not entirely caused by obstructive mechanical factors, but by mucociliary clearance problems19, favoring the non-elimination of secretions and leading to chronic rhinosinusitis11,22.

CONCLUSIONSBased on the results reported here, we concluded that:

The presence of anatomical variations of ostiomeatal complex does not necessarily mean presence of chronic rhinosinusitis. In 200 CT scans studied, approximately 50% of them presented some variation, but only 25% had concomitant chronic rhinosinusitis.

Bullous concha was the most frequently found variation, but the percentage of cases that presented this variation was similar in both groups, opening the discussion for its true role in the etiology of chronic paranasal sinuses disorders.

Intrinsic variations of nasal and paranasal mucosa may influence more significantly than OMC variations.

REFERENCES1. BERTRAND, B. - Relationship of Chronic Ethmoidal Sinusitis, Maxillary Sinusitis, and Ostial Permeability Controlled by Sinusomanometry: Statistical Study. Laryngoscope, 102: 1281- 1284, 1992.

2. BOLGER, W E.; BUTZIN, C. A.; PARSONS, D. S. Paranasal Sinus Bony Anatomic Variations and Mucosal Abnormalities: CT Analysis for Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Laryngoscope, 101: 56-64, 1991.

3. COOK, E R.; NISHIOKA, G. J.; DAVIS, W E.; MCKINSEY, J. P. - Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Patients with Normal Computed Tomography Scans. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 110: 505-509, 1994.

4. GUMUSBURON, E.; AYKUT, M.; MUDERRIS, S.; ADIGUZEL, E. - The Uncinate Bulla. Ollajimas Folia Ana J. Jpn., 73: 101-103, 1996.

5. GWALTNEY, J. W; PHILLIPS, D.; WILLER, D.; RIKER, D. - Computed Tomographic Study of the Common Cold. The New England Journal of Medicine, 330: 25-30, 1990.

6. JIANNETTO, D. F.; PRATT, M. F. - Correlation Between Preoperative Computed Tomography and Operative Findings in Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Laryngoscope, 105: 924-927, 1995.

7. JONES, N. S.; STROBL, A.; HOLLAND, I. - A Study of the CT Findings in 100 Patients with Rhinosinusitis and 100 Controls. Clin. Otolaryngol, 22: 47-51, 1997.

8. JORGENSEN, R. A. - Endoscopic and Computed Tomographic Findings in Ostiomeatal Sinus Disease. Arch Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 117: 279-287, 1991.

9. KAREN, H. C.; GERARD, A. W; BLALLE, S. - CT Evaluation of the Paranasal Sinuses in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Populations. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 104: 480-483, 1991.

10. KATZ, R. M.; FRIEDMAN, S.; DIAMENT, M.; SIEGEL, S. C. - A Comparison of Imaging Techniques in Patients with Chronic Sinusitis (X-ray, MRI, A Mode Ultrasound). Allergy Proc., 16: 123-127, 1995.

11. KENNEDY, D.; ZINREICH, S. J.; ROSENBAUM, A. G.; JOWNS, M. E. - Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Arch. Otolaryngol., 111: 576-582, 1985.

12. LANE. F. J.; SMOKER, W R. K. - The ostiomeatal Unit and Endoscopic Surgery: Anatomy, Variations, and Imaging Findings in Inflammatory Disease. Am. Jour. Roentgen, 159: 849-857, 1992.

13. LINUMA, T; HIROTA, Y; KASE, Y - Radio Opacity Office Paranasal Sinuses. Conventional Views and CT. Rhinology, 32:134-136, 1994.

14. NEWMAN, L.; PLATTS, T A.; PHILLIPS, D.; HAZEN, K. - Chronic Sinusitis Relationship of Computed Tomographic Findings to Allergy. Asthins and Cosinophiliajama, 271: 363-366, 1994.

15. OLUWOLE, M.; RUSSEL, N.; TAN, L.; GARDINER, Q.; WITITE, E - A, Comparison of Computed Tomographic Staging Systems in Chronic Sinusitis. Clin. Otolaryngol, 21: 91-95, 1996.

16. SAUNDERS, N. C.; BIRCHALL, M. A.; ARMSTRONG, S. J.; KILLINGBACK, N. - Morphometry of Paranasal Sinus Anatomy in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Arch Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 124: 656-658, 1998.

17. STACKPOCE, S.; ECLELSTEIN, D. - The Anatomic Relevance of the Haller Cell in Sinusitis. American Journal of Rhinology, 11: 219-223, 1997.

18. STAMMBERGER, H. - Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery - Concepts in Treatment of Recurring Rhinosinusitis. Part I and Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery Concepts in Treatment of Recurring Rhinosinusitis. Part II - Surgical Technique. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 94: 143-156, 1986.

19. SCRIBANO, E.; ASCENTI, G.; CASCIO, F.; VALLONE, A. - The Computed Tomographic Semiotics of Ritino-Sinusal Inflammatory. Radiol. Med. (Torino), 88: 569-575, 1994.

20. VEKEN, P J.; CLEMENT, P A. R.; KAUFMAN, L.; DERDEM, P - CT Scan Study of the Incidence of Sinus Involvement and Nasal Anatomic Variations in 196 Children. Rhinology, 28: 177-184, 1990.

21. ZINREICH, S. J. - Paranasal Sinus Imaging. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 103: 863-869, 1990.

22. WEBER, A.; MAY, A.; ILBERG, C.; HALBGUTH, A. - The Value of High-Resolution CT Scan for Diagnosis of Infectious Paranasal Sinuses Disease and Endonasal Surgery. Rhinology, 30: 113-120, 1992.

* Master in Otorhinolaryngology, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, FMRP-USE

** Ph.D., Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, FMRP USP

*** Ph.D., Professor, Department of General Medicine, FMRP USE

Master Thesis Dissertation, presented and approved by Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo. Financial Support: CAPES.

Address correspondence to: Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - Avenida Bandeirantes, 3900-14049-900 Ribeirão Preto/SP.

Article submitted on March 29, 2000. Article accepted on April 26, 2001.