INTRODUCTIONThe control of airways to keep ventilation assistance and to facilitate hygiene of the tracheobronchial tree is the basis of all treatment approaches for respiratory failure. The first record of artificial resuscitation in children was described in the Old Testament, when Elias, upon making mouth-to-mouth breathing, tried to revive a child who had probably suffered from a septic chock². One of the methods to control respiratory airways - tracheotomy - has been known for probably 3,500 years. Throughout all these years, it has been reported as a life-salving technique that is hated due to its aggressiveness².

Between 1,000 and 2,000 BC, the sacred book of Hindi medicine, Rig-Veda, mentioned it. Eber papyrus, dated 1,550 BC, described a incision similar to a tracheotomy in a man who had a fatty tumor on the neck, removing it without damaging the nerves. The Chinese book, Huang Ti Nei Ching Sû Wen, contains references to the technique. One of the most widely known procedures in the world history was reported by Alexander the Great (10BC), who made an incision with his sword on the trachea of a soldier because of a tracheal lumen obstruction caused by a bone. Probably the first tracheotomy as we know today was made by Asclepiades of Bithynia (100 BC). Aretaeus (100 BC), in his book The Therapeutics in Acute Diseases, described the tracheotomy but did not use it because of its aggressiveness. Coehus Auselilianus, in the V century BC, describe it as a fantastic, futile and irresponsible surgery. Antyluss, from Rome (340 AD), and later Paulus Aegineta, in the VII century, described tracheotomy as an incision on the third and fourth cervical tracheal rings. The Middle Age, similarly to what happened with literature, has little to add in terms of sciences and not much is known about surgeries up to the 15th century. In the 16th century, as a result of the scientific awakening, Berviens, a physician from Florence, reported as case of tracheotomy. From then on, science and art flourished: Guilielmo de Saliceto and Ambroise Paré, in France, conducted a number of tracheotomies in patients with angina. Bolondi, in Bologna, made a permanent tracheotomy due to a tracheal stenosis post-laryngeal abscess. Serratorius, in 1590, placed a metallic cannula of tracheotomy in a patient. Vesalius (1547) and Robert Hooke (1667) conducted experimental tracheotomy in dogs and placed a cannula in their trachea.

However, the surgery still remained controversial. Fabricius d'Aquapendente initially believed it was a terrible procedure, and only years later he changed his mind and started to conduct the surgery. The dramatic aspect inherent to the surgery, both life-salving and heroic, motivated a number of artists to use it. Flaubert, in his book Sentimental Education, described a tracheotomy in a child with diphtheria. Toulouse, in his picture Peon, portrayed a tracheotomy. After that period, there seemed to be no further doubts as to the advantages of tracheotomy as a life-salving technique - and a number of case reports were published. Nicolas Habicot, in 1620, described four successful tracheotomies, one of them performed in a 14-year-old boy. The boy had swallowed a bag of gold coins to avoid being mugged, and when the volume pushed the esophagus, it obstructed the trachea. After the tracheotomy, Habicot pushed the bag of coins further into the stomach and recovered it through the rectum. Caron (1766) conducted a tracheotomy in a 7-year-old boy to remove a grain of bean. Ancheu (1782) and Chevalier (1814) performed tracheotomies in pediatric patients²². George Martin (1770) described a double cannula of tracheotomy, a detail that contributed to improve the use of the technique and to reduce complications.

Goodall²², upon reviewing the literature, found until 1825 only 28 reports of tracheotomies in children. In the same year, Bretonneau published a description of a tracheotomy in a 5-year-old girl with diphtheria, a procedure that influenced the course of history of the surgery and the disease. Trosseau (1833) reported that he had saved 50 out of 200 children with diphtheria by performing tracheotomy. The surgery then became the reference for life and death, became more popular, but still presented high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Fortunately, in the 20th century, immunizations started to be used and reduced the incidence of upper airway infections, among them diphtheria. At that time, indications of tracheotomy in children became more rare. New concepts, such as intubation for ventilation support started to be used and required the surgery.

The discussion evolves around when and why to do it. The answer is not easy, because the denomination of the surgery per se, tracheotomy or tracheostomy is subject to controversy. According to Hotaling et al. (1992)¹³, both terms are indistinctly used by the literature. If we are to attain to the etymology of the word, tracheotomy derives from the Greek word tome (cut), and tracheostomy, comes from the word stomum (make a mouth or opening). The International Organization of Technical Terms defined the cut of an orifice in the trachea as a tracheotomy; and tracheostomy as the performance of a real orifice. In addition, the cannula used for such a procedure is called tracheostomy cannula. In our service, we use the term tracheotomy. Nevertheless, the key aspect is to know when to indicate and how to perform it well.

Currently, the main indications of tracheotomy may be summarized as obstruction of upper airways, ventilation assistance and pulmonary hygiene. Despite the fact that these indications have been maintained throughout the previous decades, incidence has changed and continues to evolve1,2,6,16. In the 60's and 70's, for example, infectious obstruction of the upper airways was the main indication. However, the reduction of the incidence of epiglottitis and diphtheria by vaccination resulted in the reduction of the number of tracheotomies conducted due to obstruction of upper airways22. At the end of 80's and beginning of 90's, prolonged tracheal intubation, with no estimate of extubation, and intubation sequelae (laryngeal stenosis), especially in preterm and low-birth weight babies, became the main indications for the procedure22. Other causes, such as vocal fold paralysis, either idiopathic or secondary to traumas, or manifestations of CNS, such as Arnold Chiari's syndrome, facial affections (Pierre Robin, Treacher Collins, Franceschetti etc.) may lead to respiratory discomfort and require intubation and/or tracheotomy1,16.

Recently, the increase in survival rates of children with complex problems, especially transplanted and oncologic patients, has created new populations of patients that require tracheotomy22. Arcand and Line (1988) observed a reduction in the number of tracheotomies in pre-term babies (newborns below 30 weeks of gestation) that required assisted ventilation, and attributed the finding to anesthesiologists, neonatologists, and nursing teams who have become more skillful in intubating these children, especially those with craniofacial disorders.

In infants and older children, infectious diseases such as severe tonsillitis, peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis and croup are the affections that most commonly cause obstruction of upper airwaysl8. In the case of croup and epiglottitis, they may be managed with orotracheal intubation, whereas cases of papillomatosis or severe subglottic stenosis require tracheotomy: In cases of laryngeal or tracheal foreign body, the use of a bronchoscope may help to guarantee the airway. In children with nasal or pharyngeal obstruction, oral and nasal intubation may be enough22. For children who need minimal ventilation support, CPAC may be an alternative for intubation or tracheotomy.

Therefore, when should we perform a tracheotomy? The answer is not an easy one, because we know that preterm and newborns may tolerate an endotracheal tube for a number of weeks or months, with little modifications of laryngotracheal mucosa and cartilage. In our opinion, tracheotomy should be performed if there is no estimate of extubation, in cases of excessive secretion in the airways, in order to facilitate pulmonary hygiene and to prevent an obstruction of the lumen of the cannula, or in children with psychomotor restlessness and history of spontaneous extubation. The exact timing depends on the experience of the clinical and surgical team, but the average time varies from 7 to 15 days after intubation.

As to tracheotomy, it should be performed in a surgical room, with ventilation monitoring, if possible supported by an anesthesiologist. In patients with history of chronic hypoxia, the first or second breathing of the patient may befollowed by apnea, caused by physiological dennervation of peripheral chemoreceptors, and by the sudden increase in PO2 and decrease in PCO2. In such cases, the hypoxia is responsible for stimulating the respiratory center and it is necessary to remove excessive CO2 in order to enable restoration of central chemoreceptors.

The advantage of tracheotomy over intubation is that it reduces death space and facilitates respiratory airway hygiene. However, it is not free of complications, whose severity depends on patients' age and status, primary disease, inflammatory lesions of tracheal mucosa, skills of the surgical team, material of the cannula, type of cuff and type of ventilators (pressure and volume).

To Arjmand1, complications may be divided based on time: early, intermediate and late. Kohai (1998)15, on the other hand, divide them into early and late complications. Early complications are: apnea, hemorrhage, surgical lesions of adjacent structures (esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve and cricoid cartilage), pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. Intermediate complications are: tracheitis, tracheobronchitis, tracheal erosion, hemorrhage, hypercapnia, atelectasia, decannulation of tracheotomy tube, obstruction of tracheotomy cannula, subcutaneous emphysema, pulmonary aspiration and abscess. The most common late complications are: laryngeal or tracheal stenosis, persistence of tracheocutaneous fistula, tracheal granuloma, tracheomalacea, tracheoesophageal fistula and difficulty of decannulation.

Since the authors have experienced all these problems for the past 25 years, the purpose of the present study was to review the literature and analyze the data from children submitted to tracheotomy in our service, discussing indications, complications and surgical technique. It also shows the evolution of concepts throughout the years.

MATERIAL AND METHODBetween 1975 and 1999, 73 children were submitted to tracheotomy. We studied the following variables: gender, race (white, black or mixed), term at birth, age, weight, number of previous intubations, duration of intubation, primary diagnosis, indication of tracheotomy, type of surgery (emergence or elective), presence of orotracheal intubation during surgery, complications, time of tracheotomy and decannulation. The variables were statistically analyzed by the software EPI INFO, VERSION 68.

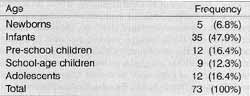

RESULTSDuring 25 years, 73 children were submitted to tracheotomy at the Service of Otorhinolaryngology of Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, involving different surgeons in the procedure. As to gender, there were 35 (47.9%) girls and 38 (52.1 %), boys. According to race, most of them were white - 61 (83.6 %), two children were back (2.7%), and ten were mixed 10 (13.7%). As to term at birth, 58 (79.5%) were term babies and 15 (20.5%) were pre-term babies (younger than 37 weeks). Age at tracheotomy varied from 15 days to 18 years, mean age of 4.2 years (Table 1).

Duration of orotracheal intubation (OTI) varied from 0 to 96 days, mean of 18 days, and the number of OTI ranged from 0 to 10, mean of 1.8 intubation.

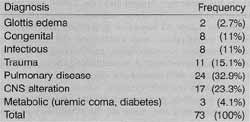

Primary diagnosis of tracheotomized children may be seen in Table 2.

After the analysis of data from Table 2, indications for tracheotomy were divided into 3 groups: pulmonary hygiene, 16 (22.2%), upper airway obstruction, 27 (37.5%), and ventilation support / prolonged intubation, 29 (40.3%).

In 60 children (83.3%) tracheotomy was an elective surgery and in 12 children (16.7%), it was an emergency surgery. During surgery, 59 (83.1%) of the children had orotracheal intubation and in 12 (16.9%) of them the surgery was conducted with oxygen mask under the assistance of a anesthesiologist. We did not obtain information about this topic in 2 cases.

The permanence of tracheotomy varied from one day to 7.8 years, mean of 15.2 months, and nine of the patients (18.8%) still have it. Eleven 11 children (22.9%), were submitted to laryngotracheoplasty because of laryngotracheal stenosis.

We observed seven early complications: two cases of pneumothorax, two cases of hemorrhage, one case of pneumomediastinum, one atelectasia and one death. Late complications described were: 20 subglottic stenosis, three cases of accidental decannulation, two cases of tracheal granuloma, two tracheocutaneous fistulae and one case of tracheomalacea.

In two children with tracheocutaneous fistula, we had to conduct a second surgical procedure in order to close the fistula.

DISCUSSIONIn our study we did not detect statistically significant difference concerning gender, and 35 children (47.9%) were girls and 38 (52.1%) were boys. Differently from our results, many authors showed a predominance of male gender, but no supporting data to justify it, such as Line et al. (88 male and 66 female)16, Carter and Benjamin (98 male and 66 female)3, Kenna et al.14 (67 male and 57 female) and Palmer et al.19 (174 male and 112 female). In our opinion, the identical percentage of male and female patients reflected the proportion of births in our service, both of pre-term and low-birth weigh babies.

As to race, we found 61 white children (83.6%), 10 (13.7%) mixed race children and two black children (2.7%). In Brazil, it is difficult to know if these data represent racial predominance, because we do not know the racial distribution of the population serviced by our ambulatory. Besides, the analysis is biased, because our hospital is a reference center and we receive referrals from other areas of the state and from outside it. Apparently, our data are similar to what the literature brings, showing a predominance of white cases, equivalent to the racial distribution of cities or countries. Once we have better demographic data about our population, we will be able to draw more precise conclusions.

TABLE 1 - Distribution of gender and moment of tracheotomy.

TABLE 2 - Distribution according to primary diagnosis.

Concerning age and cause of tracheotomy, we observed that 58 (79.5%) of the children were born at term, and 15 (20.5%) were pre-term babies, that is, gestational age below 37 weeks. In the latter, neurological immaturity and pulmonary respiratory diseases were responsible for prolonged intubation and tracheotomy. The age of children when submitted to tracheotomy varied from 15 days to 18 years, but 35 children (48.6%) were below one year of age. Comparing with data from other authors, we noticed that in the study by Carter and Benjamin3, ages at tracheotomy ranged from one week to 13 years and 50% of them were below one year of age. To Palmer et al.19 ages ranged from zero to 18 years and 31 % of the surgeries were conducted in children below one year of age and 26%, between 16 and 18 years. All in all, the authors showed that there is a decrease in the percentage of older patients and an increase in the number of tracheotomies conducted in younger children (below one year). This figure could probably be explained by the increasing number of pre-term children and infants that are placed in prolonged mechanical ventilation2,20,22.

As to indication of tracheotomy, the criteria adopted in the literature are airway obstruction, respiratory assistance and pulmonary hygiene22. Upon studying these indications, we noticed that they have not changed in the past 25 years, but that there has been a modification in its distribution. Studies conducted by other authors and us in the 70 and 80's showed that infectious upper airway obstruction was the main indication for tracheotomy1,2,16,20. Currently, we noticed a decrease in the indication of tracheotomy by infectious obstructive diseases, replaced by pulmonary diseases (ventilation support/pulmonary hygiene)19, CNS diseases (23.3%), and in older children and adolescents, trauma. As to the factor time between intubation and tracheotomy, it has changed because of the same reasons mentioned before. Between 1975 and 1980, children had intubation for few days, differently from the current situation. At that time, owing to lack of well-trained medical teams, including anesthesiologists, in addition to precarious intubation material, tracheotomy was performed earlier. In the 70 and 80's, five to seven days of intubation were indicative of tracheotomy, and currently, thanks to better technical conditions, tube material and ventilators, besides training of medical staff, the patient remains intubated for weeks or even months. Line et al.16 (1986) showed a decrease in the number of tracheotomy despite the increase in the potentially eligible population to tracheotomy. However, recent years have experienced a stabilization of this trend. We have the impression, confirmed by other authors, that it is due to an increase in the incidence of tracheotomy performed in children below one year of age, as shown above.

Our data reinforced these opinions. Duration of intubation before tracheotomy was an average of 18.3 days. Children who needed prolonged ventilation were initially intubated via orotracheal. The time to indicate tracheotomy in the group of patients depends on a number of factors, among them especially age, because pre-term babies normally tolerate the intubation tube for a number of months, with minimal edema and laryngeal inflammation. In older children and adolescents, laryngeal cartilage is more rigid and the lack of complacency results in the need for conducting tracheotomy after two or three weeks of orotracheal intubation22.

Nevertheless, intubation if children has its own risks. Gaudet et al.10 reported that age of patients, regardless of clinical conditions (previous intubation, need for mechanical ventilation), may be related to high rates of complications. The mortality rate after tracheotomy is 3% and complications rate is 22% - the younger the child, the higher the rate. Kenna et al.14 added that weight at tracheotomy may be a, significant factor and it normally represents pre term delivery and underlying disease. Kenna et al.14 found 48% of complications in term born children and 65% in pre-term children. Our data showed that 36% of the complications were present in term babies and 31 % in pre-term ones. It is a high number and we believe it may be reduced by improving the care of intubated patients, especially preventing spontaneous extubation. This piece of data is frequently reported by the literature, but it is rarely quantified.

There were 57 children (78.1%) who had fewer than 2 intubations previous to tracheotomy, and the mean was 1.8 intubation per patient. The high number of patients who developed laryngotracheal stenosis (15%) maybe explained by the number of previous intubations, resulting in difficulty to extubate and consequently to tracheotomy12. This difference may be explained by the fact that we receive children who have already been intubated by other services and, in addition, we have a high turnover of intensive physicians because we are a university hospital.

For pre-term babies, Benjamin and Carter3 believe that the use of polyvinylchloride nasotracheal tubes of reduced diameter (2.5 mm or even 2.0 mm) is an important factor for the prevention of subglottic stenosis post-intubation.

Other complications rarely observed by us were stroma granulation, vocal fold paralysis or difficulties to decannulate, except in cases of laryngotracheal stenosis. There was the death of one child who was tracheotomized and hospitalized for review of laryngotracheoplasty. She died during the night and was found in the morning. This period is problematic in terms of medical and nursing care, because the medical team is normally tired and there is a smaller number of professionals working, reducing the close monitoring provided to patients.

CONCLUSIONWe may state that tracheotomy is still a common procedure in pediatric ICUs, associated with prolonged ventilation support, although morbidity is high, especially among low-birth weight babies and infants. The improvement of surgical technique and operative care resulted in a safe procedure to support respiratory assistance.

REFERENCES1. ALBERT, A.; LEIGHTON, S. - IN CUMMINGS, C. W; FREDRICKSON, J. M.; HARKER, L. A; KRAUSE, C. J.; SCHÜLLER, D. E.; RICHARDSON, M. A. - In Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1998. 286-302 P

2. ARJMAND, E. M.; SPECTOR, J. G. - In Ballenger JJ, Snow JB. Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, 15Th ed. Media, Williams & Willdns, 1996, 466-497.

3. CARTER, E; BENJAMIN, B. - Ten-year Review of Pediatric Tracheotomy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol, 92:398-400, 1983.

4. COHEN, S. R.; CHAI, J. - Epiglottitis. 'Iwenty Years Study With Tracheotomy: Ann. Otol., 87: 461-467, 1978.

5. CROCKETT, D. M.; HEALY, G. B.; MCGILL, T J.; FRIEDMAN, E. M. - Airway Management of Acute Supraglottitis at the Children's Hospital, Boston: 1980-1985.Ann. Otol. Laryngol, 97: 114-199, 1988.

6. CRYSDALE, W S.; FELDMAN, R. I.; NAITO, K. Tracheotomies: a 10-year experience in 319 children. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 97: 439-443, 1988.

7. DUTTON, J. M.; PALMER, M. E; MCCULLOCH, T. M.; SMITH, R. J. H. - Mortality in the Pediatric Patient With Tracheotomy: Head Neck. 17: 403-408, 1995.

8. EPI INFO, VERSÃO 6. - Um programa de processamento de texto, banco de dados a estatistica para Saúde Pública em microcomputadores IBM-compatíveis.

9. FROST, E. A. M. - Tracing the tracheostomy Ann. Otol, 85: 618-623, 1976.

10. GAUDET, E T.; PEERLESS, A.; SASAKI, C. T; KIRSCHNER, J. A - Pediatric tracheostomy and Associated Complications. Laryngoscope, 88: 1633-1641, 1978.

11. GERSON, C. R.; TUCKER, G. F. - Infant Tracheotomy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 91: 1982.

12. GRAY, R. F.; TODD, W; JACOBS, I. M. - Tracheostomy Decannulation in Children: Approaches and Techniques. Laryngoscope, 108: 8-12, 1998.

13. HOTALING, A. J.; ROBBINS, W K.; MADGY, D. N.; SELENKY, W. M. - Pediatric Tracheotomy: A Review of Technique. Am. J Otolaryngol., 1992; 13: 115-119.

14. KENNA, M. A.; REILLY, J. S.; STOOL, S. E. - Tracheotomy in the Pre-term Infant. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 96: 6871,1987.

15. KOLTAI, E J. -A New Technique of Pediatric Tracheotomy: Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 1998; 124: 1105-1111.

16. LINE, W S.; HAWKINS, D. B.; KAHLSTROM, E. J.; MaCLAUGHLIN, E. F.; ENSLEY, J. L. - Tracheotomy in Infants and Young Children: The changing perspective 1970 -1985. Laryngoscope, 96: 510-515, 1986.

17. MONTOVANI, J. C.; BRETAN, O. - Traqueostomia. Analise retrospectiva de 120 pacientes. Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia, 58: 84-87, 1992.

18. MYERS, J. N.; MYERS, E. N. - In Lopes, Filho. O.; Campos, C.A.H. Tratado de Otorrinolaringologia, 1ª ed. São Paulo, Roca, 1994. 1080-1096.

19. PALMER, M. E; DUTTON, J. M.; MCCULLOCH, T M.; SMITH, R. J. H. - Trends in the Use of Tracheotomy in the Pediatric Patient: The Iowa Experience. Head Neck. 17: 328-333, 1995.

20. SCHLESSEL. J. S.; HARPER, R. G.; RAPPA, H.; KENIGSBERG, K.; KHANNA, S. - Tracheostomy: Acute and Long-term Mortality and Morbidity in Very Low Birth Weight Premature Infants. J. Pediatric. Surg., 28: 873-876, 1993.

21. TOM, L. W C.; MILLER, L.; WETMORE, R. F.; HANDLER, S. D.; POTSIC, W P - Endoscopic Assessment in Children With Tracheotomies. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 19: 321-332, 1993.

22. WETMORE, R. F. - In Bluestone, C. D.; Stool, S. E.; Kenna, M. A. Pediatric Otolaryngology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Company, 1996, 1425-1439.

Resident of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - UNESP.

** Full Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - UNESP

*** Assistant Professor of the Discipline of otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu -UNESP

**** Assistant Professor of the Department of Public Health, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - UNESP

Study conducted at the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery of Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu - Department of Ophthalmology, Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery - UNESP - São Paulo.

Study presented at 35° Congresso Brasileiro de Otorrinolaringologia, which was awarded a special citation.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Dr. Jair Cortez Montovani - Departamento de Oftalmologia, Otorrinolaringologia a Cirurgia de Cabeça a Pescoço, da Faculdade de

Medicina de Botucatu - UNESP - 18618-000 Botucatu /SP - Brazil - Tel/fax: (55 14) 6802-6256.

Article submitted on August 15. 2000. Article accepted on October 20, 2000.