INTRODUCTIONMucoceles are benign lesions that are cystic, expansive and limited to their own epithelial lining, revealing the accumulation of mucous secretion inside a blocked cavity².

It is a relatively rare condition most frequently found in the fronto-ethmoidal region19.

It is believed that the blockage is a consequence of an obstructive factor in the drainage duct of the sinus. It may have different etiologies: infectious, traumatic, tumoral or congenital. Growth is slow and takes place for many years. If the mucoceles becomes infected, it is transformed into a mucopyocele¹². Treatment is essentially surgical and consists of opening the blocked cavity and creating an extensive communication channel with the nasal fossa. In the past, these surgeries were conducted only via external approach, whereas currently they may be conducted endoscopically or using both associated approaches.

The author reported cases of advanced Pronto-ethmoidal mucoceles and pyocele of the maxillary sinus and middle concha followed by the Service of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de Sao Paulo, presenting clinical picture, intraoperative findings and post-surgical results.

REVIEW OF LITERATUREMucoceles is a benign lesion that affects both genders. The term mucoceles was used by Roullet in 1896, although the first description had been published in 1785 by Henry Nucalai. In most cases, patients are aged between 30 and 50 years, but it may also affect children³.

The most frequent mucoceles affects the frontal sinus (70%), followed by ethmoidal, maxillary and sphenoidal sinuses. These sinuses may also have mucopyocele, but it is much more rare. Any part of the ethmoidal complex may be affected, including the concha bullosa. Frontal and ethmoidal sinuses are more frequently affected, probably because of the complicated and variable system of drainage of these sinuses9.

They are affections of the epithelial lining that contains mucus. They may be destructive and radiologically imitate malignant tumors. Traditionally, it has been described that mucoceles may have primary or secondary origin 4. Primary mucoceles would be originated from the blockage of a mucosa gland of, the submucosa 5.

This theory is not acceptable for many reasons:

1. There are few mucosa glands in the frontal sinus, differently from the maxillary sinus;

2. Although there is frequent cystic retention in the maxillary sinus, the incidence of maxillary mucoceles is low. Cystic retention does not show bone destruction, which is present in mucoceles 14;

3. Histological study of mucoceles did not show evidence of pre-existing retention cysts in the origin of mucoceles 13; 4. Mucoceles is considered a secondary consequence of the obstruction of the drainage sinus. This hypothesis has been accepted as the main cause of the pathology¹³, 4.

The theory is supported by the high incidence of mucoceles in the frontal sinus because of its anatomy. Zizmour and Noyek19, in 1968, listed extrinsic causes as the predominant ones, such as infection and trauma. Intrinsic causes, such as cystic fibrosis, are also responsible for secretion stasis in the sinus.

Although drainage blockage is a consensus in the etiopathogenesis of mucoceles, its exact mechanism is still undefined.

The "Pressure theory" was based on the observation of the changes on the epithelium that recovers the mucoceles. The mucosa would go from columnar pseudo-stratified to low columnar or cuboidal with few goblet cells. Changes would become more marked as a result of time. Recently, Lund and Milroy (1991)'° proposed a new theory - the "dynamic theory", based on the obstruction of the duct associated with a superinfection. Contamination would stimulate production of cytokines by lymphocytes and monocytes, increasing the synthesis of prostaglandin and colagenase in the Abroblasts of the mucus lining. These cells, in turn, would stimulate reabsorption and consequent expansion of mucoceles. On the other hand, this dynamic theory shows that there is reabsorption and bone neoformation.

Wigh in 1950 18 showed a zone of sclerosis by osteolytes on the margin of the lesion, observed in the x-ray. Other authors, Zizmour and Noyek, in 1968'9, found macroscopic calcifications in 5% of the cases, as well as in the x-rays, showing the formation of new bone.

As to contamination of cavity, Lund and Milroy, in 1991¹°, performed a study in which they obtained 52% positive results for microorganisms, and Staphylococcus aureus and albus were the most frequent ones. They also isolated Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzaeand Escherichia coli.

Mucus is frequently seen in the cavity in a two-layer presentation: the lower one is dark and thick, and the upper layer is thinner, sometimes simulating CSF. The sedimentation may have a homogenous appearance in the MRI. Anyhow, the brown thick secretion may suggest the presence of fungus and culture and histological exams may be required to identify it¹¹.

Symptoms caused by mucoceles do not depend on the affected region. Since it is an infiltrating disease, it invades the adjacent organs, such as the orbit, nasal fossae and anterior cranial cavity. Fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles frequently leads to proptosis, pushing the eye downwards and to the side16.

Figure 1. Large volume of mucoceles, with bulging of the frontal region, recovering the upper half of the nose.

Figure 2. CT at axial section showing impairment of anterior ethmoidal cells and frontal sinuses bilaterally. Displacement of both ocular, globes.

If not properly treated, some complications may derive, such as intracranial infection (formation of abscess or meningitis), or secondarily, because of mass effect, it may cause damage to the orbit or the content of the anterior cranial fossa 16.

Facial esthetical alterations and nasal obstructions are frequent in maxillary and middle concha mucoceles. They are less frequent if compared to fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles, amounting to about 3 to 10%. In Japan, the incidence of maxillary mucoceles seems to e higher than in other countries6.

Mucoceles may become infected, and if this happens, it is named mucopyocele or pyocele.

The essential exams to define diagnosis are radio-imaging techniques: CT scan and MRI. Ultrasound may be used as a diagnostic support, especially to differentiate sinusal lesion from orbital lesion.

Treatment of mucoceles has been modified, especially due to the advances in endoscopic surgery. In the recent past, all cases of mucoceles were treated with external approach, using Lynch-Howarth incision or osteoplastic flap. As to maxillary mucoceles, the access is through Caldwell Luc approach.¹¹

Kennedy et al., in 1989 7, published a series of 18 cases, and they were all treated with endoscopic access and marsupialization. The result was zero percent recurrence after a minimum follow-up of 18 months. The trends today is to use endoscopic access or the combination of endoscopic and external approach.

CASE REPORTCASE 1 (giant frontal mucoceles)

TMJ, aged 56 years, female patient, had a history of constant nasal obstruction on the left for 10 years, followed by progressive bowing of frontal region, progressing to diplopia and impairment of visual acuity on the left.

ENT exam: cystic lesions that went beyond the limits of the frontal region, recovering partially the nasal dorsum on the region of glabella (Figure 1). The left eye was completely recovered by the lesion, whereas the right eye was partially recovered.

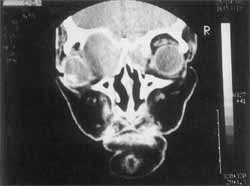

Computed tomography at axial section showed an expansive lesion with homogenous content, deviating outwards both orbits (Figure 2). At coronal section, the lesion with the same characteristics affected both anterior ethmoidal sinuses, significantly larger than on the left (Figure 3).

She did not refer previous surgeries.

Treatment approach: Osteoplastic approach of frontal sinus by coronal access. The external wall was destroyed by the lesion. A large amount of dark brown liquid was removed. Cleaning of both frontal sinuses and the wide opening with nasal fossae was maintained after ethmoidectomy. Periosteum was preserved and used in the attempt to reconstruct the frontal region. Immediate post-op was uneventful and 15 days after surgery the patient was esthetically better (Figure 4).

Figure 3. CT scan at coronal position showing mucoceles bilaterally occupying the anterior ethmoidal complex, significantly larger on the left.

Figure 4. 15th day post-operative - no frontal bulging.

Figure 5. CT scan at coronal section showing septated cavity in left maxillary sinus, forming mucoceles.

Figure 6. Caldwell-Luc incision with opening of anterior wall of maxillary sinus showing mucus purulent secretion inside it.

CASE 2 (maxillary mucoceles)

LLR, a female patient aged 67 years, had a history of tumor on the left gum for two years, with slow and progressive growth, impairing the placement of the upper dental prosthesis.

She was submitted to bilateral transmaxillary sinusectomy 40 days before.

ENT exam: increase in volume at the alveolar region and gingival-labial sulcus.

CT scan revealed the presence of homogenous mass on the left maxillary sinus, extended downwards and pressing the orbital margin (Figure 5).

Treatment approach: Caldwell-Luc approach on the left. After opening of the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, we could see the presence of mucus inside it, confirming the diagnosis of maxillary sinus pyocele (Figure 6).

CASE 3 (middle concha mucoceles)

Figure 7. Anterior rhinoscopy showing a smooth mass at the level of nasal vestibule.

Figure 8. CT scan at coronal section, showing homogenous content occupying all left nasal fossa.

EFS, a male 10-year old patient, had a history of constant nasal obstruction on the left for 3 years, night snoring and oral breathing. He did not report allergic symptoms nor nasal bleeding.

ENT exam: Smooth red mass occupying almost all left nasal fossa, preventing visualization of nasal structures. Significant septum deviation to the opposite site (Figure 7).

CT scan showed a lesion consisting of homogeneous mass that occupied the whole left nasal fossa and pushed the nasal septum to the opposite side (Figure 8).

Treatment approach: Marsupialization with intra-nasal access. We emptied the content of the lesion via nasal access. Opening of all cells that comprised the middle turbinate, leaving its medial limit. It also included cleaning of ethmoidal cells. Next, we proceeded with correction of septum deviation, placing it to the opposite side.

DISCUSSIONMucoceles occupies any paranasal cavity or middle concha and it is not difficult to diagnose. The history reported by patients dates back a long time and mucoceles produces a wide range of symptoms and signs of orbital alteration, without previous affection of paranasal sinuses. We should consider some differential diagnosis if there is proptosis, orbital displacement, ophthalmoplegia, decrease of visual acuity, history of trauma, sinusal surgery and chronic inflammations.

Early diagnosis, supported by CT scan and MRI, prevents progression of the disease, which, despite its benign characteristics, grows and causes erosion of bone walls, deviating the orbit, compressing the ocular globe or the optic nerve. It may also present intracranial invasion, and under such conditions, MRI is the key exam that differentiates the lesion from the cerebral content.

Maxillary mucoceles is less frequent and it occurs in cases already submitted to sinusectomy, with formation of septated cavities, or even malformation, in which the cavity is divided and creates an isolated compartment, without drainage or cystic degeneration of mucosa.

As a result of symptoms, there is bulging of cheeks, causing facial asymmetry, nasal obstruction, dental problems and diplopia.

CT scan, in most situations, is homogenous and isodense with the brain and it does not highlight the contrast, except when it is infected - then it is peripherally contrasted. We can easily find mucopyocele, as shown in the case reported here.

When there is no bone erosion, differential diagnosis should be made with dental origin or cystic retention in case of rhinosinusitis with extensive polyposis. In case of bone destruction, differential diagnosis should be made with malignant tumors of different natures.

Middle concha mucoceles, in fact, is frequently pyocele, because in the physical exam we observe a large mass that occupies the whole nasal fossa, expands to the middle line and pushes away the septum from the inferior concha. In many occasions, we can see a salience in the vestibule, deforming the nasal dorsum. The main complaint of the patient is progressive nasal obstruction, and the site potentially appropriate to develop mucoceles/pyocele is the anterior portion of middle concha, because of pneumatization.

A well pneurnatized concha, also called concha bullosa, may have a blocked ostium and develop mucoceles. Concha bullosa, if present, requires surgery to avoid the blockage of ethmoidal infundibulum, usually associated with maxillo-ethmoidal chronic rhinosinusitis¹.

Mucoceles normally consists of pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium. Lund and Milroy, in 1991¹°, found some associations with areas of squamous epithelium (15/40) or a case with both types of epithelium - squamous and cuboidal. The presence of globet cells was found in 67% of the cases and showed evidence of hyperplasia in half of the cases. The number of serous-mucous glands did not increase in relation to the normal epithelium of the sinuses.

Treatment of mucoceles, regardless of the affected sinus, is always surgical. As to the most affected sinuses respectively frontal, ethmoidal, maxillary and sphenoidal, we should promote drainage in order to enable communication of sinuses and nasal fossa.

During a long time, treatment consisted of the complete removal of mucosa that recovered the sinuses16. It is still true if there is marked impairment of the area. If not, we conduct marsupialization enabling good airing through the respective ostia.

Endonasal endoscopic approach is ideal for the treatment of mucoceles, especially in young patients, who have little morbidity.

In the case of fronto-ethmoidal affection, we may use the technique of Lynch or osteoplastic approach, if we intend to explore the external access.

In the case reported here, there was no external portion of frontal and we decided to make a coronal incision, using the periosteum; plus removal of excessive skin to improve the esthetic aspect.

It is not always possible to use the endoscopic technique either because it is not appropriate to the case or because of lack of experience by the professional'. It is sometimes possible to associate both techniques.

As to maxillary mucoceles or pyocele, it was treated with the technique of Caldwell-Luc, maintaining a wide opening through the ostium of the ostiomeatal complex. The mucopyocele of middle concha was solved with intranasal macroscopic surgery.

CONCLUSIONEarly diagnosis of mucoceles is very important and it prevents the expansion from destroying orbital or ocular alterations, which are the most frequent ones.

The most important complication is intracranial extension.

The treatment should be employed as soon as the diagnosis is made, which is made possible today by radioimaging techniques.

Prognosis is normally good and the technique to be used may be endoscopic or external, and professionals should always choose the one they are more familiarized with and can perform better.

REFERENCES1. BLAUGRUNG, S. M. - The nasal septum and concha bullosa. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am., 22: 219-306, 1989.

2. CANALIS, J. G.; ZAJTCHUK, J. T.; JENKINS, H. A. - Ethmoidal Mucoceles. Arch. Otolaryngol., 104: 268-91,1978.

3. DIAZ, F.; LATCHOW, R.; DUVALL, A. B. Mucoceles with intracranial and extracranial extensions: Report of two cases. J. Neurosurg., 48 284-8, 1978.

4. EAST, D. Mucoceles of the maxillary antrum. J Laringol. Otol., 99. 49-56, 1985.

5. FASCENELLI, F. W. - Maxillary sinus abnormalities. Arch. Otolaryngol., 90: 190-4, 1966.

6. HASEGANYA, M.; SAITO, Y.; WATNABE, L; KERN, E. B. Postoperative mucoceles of the maxillary sinus. Rhinology, 17 253-6, 1979.

7. KENNEDY, D. W.; JOSEPHSON, J. S.; ZINREICH, S. J.; MATTOX, D. E.; GOLDSMITH, M. M. - Endoscopic sinus surgery for mucoceles: A viable alternative. Laryngoscope, 99. 885-95, 1989.

8. KPEMISSI, E.; BALD, K.; KPODZRO, K. - Mucoceles sinusiennes -Ann. Otolaryngol. Chir. Ceruicofac., 113: 17982, 1996.

9. KRISHNAN, G.; KUNAR, G. - Fronto-ethmoid mucoceli: one year follow-up

endoscopic fronto-ethmoidectomy. J. Otolaryngol., 25(1): 37-40, 1996.

10. LUND, V. J.; MILROY, C. M. - Fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles: a histopathological analysis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 105: 921-3, 1991.

11. LUND, V. J. - Endoscopic Management of paranasal sinus mucoceles. J Laryngol. Otol., 112: 36-40, 1998.

12. LUND, V. J. - Anatomical considerations in the etiology of fronto-ethmoidal mucoceles. Rhinology, 25: 83-8, 1987.

13. NATVIG, K.; Larsen, T. E. - Mucoceles of paranasal sinuses. J. Laryngol. Otol., 92: 1075-982, 1978.

14. PAPARELLA, M. N. - Mucosal cyst of the maxillary sinus. Arch. Otolaryngol., 77: 650-7, 1966.

15. PARDAG, R. J. L.; Alba, F. B. - An ORL lber. Am., 2: 1218,1994.

16. SHEFFIELD, R. W.; COSSISI, N. J.; KARLAN, M. S. Complications of sinusitis: what to watch for. Post grad. Med.; 63: 93-6, 99-101, 1978.

17. STIERNBERG, C. M.; BAILEY, B. J.; CALHOUN, K. H. Management of invasive fronto-ethmoidal sinus mucoceles. Arch. Otolaryngol., 112 (10): 1060-3, 1986.

18. WIGH, R. - Mucoceles of the fronto-ethmoidal sinuses. Radiology, 54:579-90, 19.50.

19. ZIZMOUR, J.; NOYEK, A. M. - Cysts and benign tumors of the paranasal sinuses. Sem. Roentgenol. 3: 172-85. 1968.

* Joint Professor of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

** Physician of the Specialization Course of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

*** Resident Physician of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

**** Post-Graduate studies under course at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Article submitted on January 20, 2000. Article accepted on June 9, 2000.