INTRODUCTION There are very few data in the literature concerning ingestion of caustic substances by the population, sometime: nothing more than estimates. Moore¹² reported that it is estimated that 1 in each 200,000 inhabitants per year search for medical treatment because of ingestion of acid or alkali. It represents the same as 1,100 annual cases in the Unites States. According to Sobel 17, however, this figure corresponds only to the portion of patients that come to the hospitals, that is; the correct figure representing the American population that manipulates such substances would be 1 in each 3,000 inhabitants, or 70,000 cases per year. Howell et al. 7 estimated that the number of cases would fall within 5,000 and 15,000 and Anderson et al.¹ believed that the figure would be 26,000, that is, 12 cases in each 100,000 inhabitants, 17,000 of them only in children (65%). Christesen² found in Denmark 10.8 cases per year in each 100,000 inhabitants, and half of them were patients under 5 years of age. Marti et al.¹¹ found in Barcelona that caustic ingestion was responsible for 7% of the deaths caused by ingestion of poison, and narcotics were responsible for 64.6% of 486 deaths that took place between 1986 and 1989. In the region of Ribeirão Preto, we detected fewer than 0.5 case in each 100,000 inhabitants that came to the hospital¹°.

Skinner and Belsey 16 warned that the incidence of caustic ingestion is still high in Eastern Europe and Middle East; according to the authors, it is justified by the lack of strict legislation to control such substances. On the other hand, in Finland, there are no cases of caustic ingestion because these products have been banned from commercialization in the country since 1969¹³. Therefore, the authors stated that accidents of caustic ingestion in that country involve ingestion of dishwasher soap and vinegar. Whereas in Denmark, among the patients who had contact with caustic substances, half of them had esophageal damage², in Finland these lesions were present in only 20% of the cases¹³.

The chemical substances that promote destruction of tissues are considered caustic because they react with essential products for the survival of cells, by means of liquefaction or coagulation. Many substances cause damage, but alkalis and acids seem to have more tissue-destructive potential. Due to the action mechanism of acids, which promotes the dehydration of cells (coagulation), they form scars on necrotic tissue, preventing them from acting deeper. The fact that the gastric juice does not have potential to neutralize it contributes to the onset of lesions in various organs, such as the stomach and intestines, mouth and esophagus.

The action mechanism of alkali agents is the combination of these agents with tissue proteins, forming proteinates, and the combination with fats, promoting the reaction of saponification. When we eat proteins and fats they promote the formation of liquids - water, leading to necrosis of liquefaction. The formed products favor penetration of remaining alkali in the tissue, because it is more soluble and reaches easily the deeper tissue layers, consequently, causing damage to the whole organ exposed to the substance. Alkalis promote thrombosis of blood vessels, hindering irrigation of the organ. However, the alkali may be neutralized, at least partially, by gastric secretion, reducing its power of action over the mucosa of the stomach. For this reason, it is normally the acids that cause more severe damage to this organ, especially in the antrum-pyloric region. We should keep in mind, however, that there are people who normally have achlorydria, and under such circumstances the destruction of the alkali is much more severe. Similarly, since the esophagus has a slightly alkaline pH, its epithelium is resistant to acid and only 6 to 20% of those who ingest the substance have local damage.

In addition to type of caustic, lesions caused in the body depend on quantity, concentration and duration of contact with the mucosa. This last variable is responsible for the heterogeneous patterns of lesions caused on the airways and digestive tract of patients, or sometimes in the same anatomical region. These lesions, when located in the esophagus, are frequently described whereas those of the pharyngolaryngeal region are not well known.

The purpose of the present study was to describe pharyngolaryngeal damage in the acute and chronic phase resultant from caustic ingestion, presenting symptomatology and recommended treatment.

MATERIAL AND METHODData presented in the current study refers to the analysis of the photos of the mouth and pharyngolaryngeal region of 6 patients at different phases of caustic ingestion. These patients were selected from a series of 41 patients who ingested caustic soda, according to the following criteria:

• To have been treated at HC, FMRP-USP, a university hospital, tertiary reference for the past five years.

• To have been submitted to videolaryngoscopy.

Data collected from patients are presented in Chart 1. Images were obtained by means of videolaryngoscopy or videofibroscopy, conducted under local anesthesia. Videolaryngoscopy was performed using a rigid endoscope with 70° Hopkins lenses and a micro camera. To perform videofibroscopy, we used a bronchofibroscope P-20, in addition to a micro camera. Photos were obtained with videoprinter.

CHART 1 - Distribution of patients according to gender, race, age, moment of ingestion and videolaryngoscopy.

Key: M = male; F= female; Br = Caucasian.

In the chronic phase of. caustic ingestion, videolaryngoscopy was performed while the patient was seated and we pulled the tongue forward in order to have a better view of the larynx. In the acute phase, however, the presence of tongue damage prevents it from being pulled and videolaryngoscopy was performed by asking the patient to lean forward. Rhinopharynx exams were conducted with fiberscopes.

RESULTSWhen analyzing the exams, we noticed that patient 1, two days after caustic ingestion, had bright red areas without papillae on the body of tongue, especially on the edges and dorsum; some areas were recovered with fibrinous tissue and other by necrotic tissue (Figure 1). Patient 5, fifteen days after caustic ingestion, still showed bright red ulcers with clear limits on the dorsurri of tongue, soft palate and tonsillar pillars; however, there were some areas forming fibrosis, which bled easily upon touch. At the end of hard palate, there were no ulcers, only fibrosis. The teeth had whitish incrustations and the underlying mucosa was red. In the jugal mucosa there were perpendicular fibrotic striae that limited mouth opening because of the pain triggered by the stretching. Thirty days after ingestion (patient 4), the ulcers were gone and there was only fibrosis - the chronic phase.

In the chronic phase, we noticed fibrotic areas in the oral cavity of patients, especially in the hard palate and less intense in the dorsum of tongue (patients 2, 3 and 6). In the transition soft-hard palate, fibrosis was more marked, forming a thick bridge, which was a perpendicular fibrotic branch towards the faucial arch, puling it upwards and deviating the uvula to the damaged side - patient 3. This fibrosis compromised the shadow that the soft palate has over the oropharynx.

At the level of the rhinopharynx-oropharynx transition, fibrosis forms a ring at the horizontal plan, attaching the opposite tonsillar pillars and the soft palate to the lateral and posterior wall, thus reducing the area of Passavant's ring (patient 3). This fact reduced palatal movement and airflow in nasal breathing, resulting in production of nasal voice. The posterior wall of oropharynx in this patient was all fibrotic, and there was no evidence of normal mucosa.

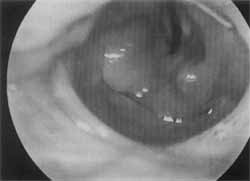

In three patients, fibrotic lesions were more intense, as we went deeper into the larynx. In patients 2 and 4, the necrosis destroyed the two superior thirds of epiglottis, exposing the larynx to saliva and food bolus. The contact of saliva in the posterior region results in constant edema and hyperemia, leading to absence of protection provided by epiglottis (Figure 2). There was a fibrotic ring on the horizontal plan, from the stump of the epiglottis to the vallecula and lateral and posterior walls. This fibrotic ring was thin and maintained the oropharynx permeable to food and saliva. However, in patient 3, epiglottis was not destroyed and its free margin merged with lateral and posterior walls of the pharynx, closing completely the oropharynx-hypopharynx transition. This patient was submitted to esophagopharyngoplasty and 10 years later had a small orifice on the site, through which he easily breathed and was fed, according to him (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Fibrous ring in the oropharynx-hypopharynx. transition, showing destroyed epiglottis and edema of aryepiglottic folds.

Figure 3. Recurrence of stenosis 15 years after esophagopharyngoplasty, maintaining an orifice for feeding and breathing.

During esophagopharyngoscopy of patient 3, we observed that the upper portion of retrocricoid region was not affected by fibrosis; however, somewhat below, the walls of hypopharynx merged with the retrocricoid closing completely the passage of food. The fibrosis went downwards through the esophagus and stomach.

In the acute phase, diagnosis was easier because the severe pain experienced by patients made them reveal the contact with the caustic substance. The presence of damage at oroscopy reinforced the diagnosis. The exam of pharyngolaryngeal region is important to localize ulcerations, however, this exam is not always performed because it depends on physical and psychological conditions of patients. In the chronic phase, in addition to oroscopy, videolaryngoscopy, rhinofibroscopy, esophagoscopy and first phase of swallowing, esophageal seriography was essential to characterize stenosis and recommended treatment.

In the acute phase of caustic ingestion, respiratory difficulties required the use of corticosteroids in patient 2 to enable proper ventilation. In the chronic phase, in patients 3 and 6, we conducted esophagopharyngocoloplasty.

DISCUSSIONLesions caused by caustics are not homogenous, varying from region to region and sometimes even within the same region, because during swallowing there are areas of morf or less contact. The same fact has been observed by other authors8, 6, when they confirmed that severity of caustic lesions depend on duration of exposure of tissue to caustic substance. Mouth and esophagus are the regions that are more frequently affected when swallowing.a caustic substance, that is to say, the absence of pharyngeal lesions does not mean that the esophagus has not been damaged.

On the first days, ulcerations remain bright red or recovered by fibrin-leukocyte tissue or necrotic material. These lesions show the path of the substance, its extension and depth. Severe cases, with large areas of necrosis, may progress with infection, perforation of organs (more common in the esophagus), and abundant bleeding (arterial damage), threatening the life of patients. Another complication normally observed is cerebral abscess (1%), due to cerebral metastasis of infections existent in the digestive tract 9.

In the oral cavity, the areas that have more contact with caustics are hard palate, dorsum of the tongue and jugal area; in the oropharynx, they are the soft palate and tonsillar pillars; and in the hypopharynx region it is the retrocricoid region. In the esophagus, inferior and middle thirds are more affected in adults, whereas the superior third is more affected in children, owing to the presence of an anatomical stricture that provides more contact of caustic and mucosa. The epiglottis is the most. compromised structure of the larynx, especially its free margin, in which there may be necrosis, reaching and even destroying the epiglottic cartilage. Aryepiglottic folds, when traumatized, become edematous, and together with the edematous epiglottic, they generate laryngeal stridor. Internal areas of larynx, especially the false vocal folds and the vocal folds, are not generally affected.

In the chronic phase, fibrosis is fixed in layers whose deepness depends on the severity of the caustic damage. If it is only a lesion of the epithelial layer, it will cure quickly, even without treatment. However, for more severe lesions, the fibrosis may pose the patients' life at risk because they are unable to breathe or feed themselves. Fibrosis is more intense in the esophagus, because the time of contact with the mucosa is longer, once this organ has a thinner caliber. On the other hand, severe lesions in the pharynx are more rare because it is an organ of thicker caliber. However, there are situations, such as suicidal attempts, in which fibrosis is so severe that it obstructs completely the pharynx (patient 3).

At the level of pharynx, three regions are important, gradually increasing its severity: rhinopharynx-oropharynx transition, oropharynx-hypopharynx transition and hypopharynx. In the 2 first regions, fibrosis tends to be located at a horizontal plan, whereas in the hypopharynx it tends to be longitudinal. The presence of ulceration of the free margin of epiglottis, concomitant with ulceration of pharyngeal lateral and posterior walls, makes the epiglottis attach to these walls, closing partially or totally the oropharynx. In the latter configuration, it is impossible to pass food, saliva or even air for breathing. These patients depend on tracheostomy and gastrostomy to breathe and feed themselves, and they can not produce good vocal sounds.

We should point out that the manifestation is progressive and the final configuration of stenosis may take month: to be defined. Because of that, when the patient is examined, 7 to 15 days after ingestion, it is possible that the esophagogram reveals a picture of caustic esophagitis. This radiological study may reveal mild stenosis, if conducted after one week, or severe stenosis if conducted 30-60 day: later. In a study, regardless of the ingested amount, we found 73% of esophagus stenosis and 32% of stomach damage it patients that had ingested exclusively caustic soda. The situ ation in which there is pharyngeal damage (severe stenosis; is found in cases of ingestion of 2 to 3 spoons of caustic soda, when the percentage of esophageal stenosis reaches 90% and stomach stenosis is 41%¹². It is estimated that pharyngolaryngeal damage is present in 10-15% of patient; that ingested caustic soda. Mamede, in 239 cases, found two cases (1%) in which there was merger of epiglottis to pharyngeal lateral and posterior walls, preventing the entry of air and food 9.

If there is laryngeal lesion (aryepiglottic fold and/or epiglottis), the patient has dyspnea and laryngeal stridor in the acute phase, and in these cases, we should administer steroids to reduce the edema and the inflammatory process and improve pulmonary ventilation. In situations in which there is no improvement in dyspnea with corticosteroids, oral or nasotracheal intubation or tracheostomy are indicated³. In cases that require intubation, Shikowitz et al.15 recommended careful orotracheal intubation provided that the laryngeal and base of the tongue edema did not preclude direct view; however, if intubation had to be made blindly, tracheostomy was recommended.

We believe that esophageal seriography and esophagoscopy performed after the second week of ingestion are enough for the therapeutic planning of stenosis, although Scott et al. 14 indicated the need to use CT scan and cinepharyngoesophagography to detect dysfunctions of pharyngeal muscles.

In the chronic phase of caustic ingestion, we have frequently indicated esophagopharyngoplasty for cases of moderate or severe esophageal stenosis, differently from Ferguson et al .4, who indicated it only in severe cases, and Gossot et al.5, that contraindicated the surgery. Pharyngeal stenosis is followed by severe esophageal stenosis, one of the indications of esophagopharyngoplasty. One of the most feared complications of this surgery is restenosis of anastomotic mouth. To reduce the incidence of restenosis we should apply a pharyngocolic anastomotic suture on a pharyngeal site that has intact mucosa. In order to achieve that, it is essential to inspect the conditions of the oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal mucosa with laryngoscopy during surgical planning. The presence of fibrosis detected at videolaryngoscopy characterizes bad sites to apply sutures. Areas of pale mucosa should be equally avoided, because paleness is a result of thrombosis of nourishing vessels and bad irrigation contributes to hypertrophic scarring. Fortunately, restenosis is not complete in many situations, because the fibrosis respects the area in which the mucosa from the colon was applied. Therefore, this is an orifice through which the patient may be fed and breathe (Figure 3). This surgery, when successful, provides good quality of life to patients.

CONCLUSIONSBased on the observations made, we concluded that:

1, Pharyngolaryngeal lesions are not homogenous and are gradually more severe from rhinopharynx-oropharynx transition; oropharynx-hypopharynx transition to hypopharynx; we may observe total obstruction at the two last levels.

2. In the larynx, only the aditus is impaired, in the presence of stridor.

3. Esophagopharyngoplasty seems to be the right choice to correct pharyngeal stenosis, although there may be restenosis.

REFERENCES1. ANDERSON, K. D.; ROUSE, T. M. & RANDOLPH, J. G. - A controlled trial of corticosteroids in children with corrosive injury of the esophagus. N. Engl. J. Med., 323: 637-40, 1990.

2. CHRISTESEN, H. B. T. - Epidemiology and prevention of caustic ingestion in children. Acta Pediatrica, 83: 212-15,994

3. CHRISTESEN, H. B. T. - Caustic ingestion in adults - epidemiology and prevention. Clinical Toxicology, 32: 557-68, 1994.

4. FERGUSON, M. K.; MIGLIORE, M.; STASZAK, V. M. & LITTLE, A. G. - Early evaluation and therapy for caustic esophageal injury. Am. J. Surg., 157 116-120, 1989.

5. GOSSOT, D.; SZOULAY, D.; PIRIOU, P.; SARFATI, E. & CELERIER, M. - Use of the colon for esophageal substitution. Mortality and morbidity. Report of 105 cases. Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologigue, 14: 977-81, 1990.

6. HOLINGER, L. D. - Caustic ingestion, esophageal injury and stricture. In: Holinger, Lusk RP, Green CG. editors. Pediatric laryngology & bronchoesophagology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 295-303, 1997.

7. HOWELL, J. M.; DALSEY, W. C.; HARTSELL, F. W. & BUTZIN, C. A. - Steroids for the treatment of corrosive esophageal injury: a statistical analysis of past studies. Am J Emergency Medicine, 10: 421-25, 1992

8. KREY, H. - On the treatment of corrosive lesions in the esophagus. Acta Otolaryngol., S102: 9-49, 1952.

9. MAMEDE, R. C. M. - Esofagite Cáustica: variáveis socio-demográficas, motivo da ingestão a terapêutica numa serie histórica. Tese de Livre Docência, apresentada a FMRP-USP, 1999.

10. MAMEDE, R. C. M.; MELLO FILHO, F. V.; ENTSCHEV, B. M. - Incidência a diagnóstico da ingestão de cáustico. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol., 66: 208-214, 2000.

11. MARTI AMENGUAL, G.; REIG BLANCH, R.; SANS GALLEN, P. et al. - Deaths from poisoning in Barcelona, 1986-89. Revue d Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique, 40: 102-07, 1992.

12. MOORE, W. R. - Caustic ingestion-pathophisiology, diagnosis, and clinical treatment. Clinical Pediatrics 25: 192-196, 1986.

13. NUUTINEN, M.; UHARI, M.; KARVALI, T. & KOUVALAINEN, K. - Consequences of caustic ingestion in children. Acta Paediatrica, 83: 1200-05, 1994.

14. SCOTT, J. C.; JONES, B.;EISELE, D. W. & RAVICH, W. J. Caustic ingestion injuries of the upper aerodigestive tract. Laryngoscope, 102: 1-8, 1992.

15. SHIKOWITZ, M. J.; LEVY, J.; VILLYEAR, D.; GRAVER, M. et al. - Speech and swallowing rehabilitation following devastating caustic ingestion: techniques and indicators for success. Laryngoscope, 106: 1-12, 1996.

16. SKINNER, D. B. and BELSEY, R. H. R. - Corrosive strictures of the esophagus. In: Management of esophageal disease. W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, pp.694-714, 1988.

17. SOBEL, R. - Traditional safety measures and accidental poisoning. Childhood, 811: 16-20, 1969.

* Associate Professor, Head of the Discipline of Head and Neck Surgery at the Department of Surgery, Orthopedics and Traumatology at Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo.

** Foreign Visiting Physician of the Discipline of Head and Neck Surgery at Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo.

Study conducted at the Service of Head an Neck Surgery of Hospital das Clínicas and Department of Surgery, Orthopedics and Traumatology at Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo

Study presented at I Congresso Triológico de Otorrinolaringologia, held on November 13 -18, 1999, in São Paulo /SP.

Study sponsored by CNPq.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Dr. Rui Celso Martins Mamede - Rua Nélio Guimarães, 170 - Alto da Boa Vista - 14025-290 Ribeirão Preto /SP.

Fax: (55 16) 623-1350 - E-mail: rcmmamed.@.rgm.fmrp.usp.br

Article submitted on May 23, 2000. Article accepted on November 1, 2000.