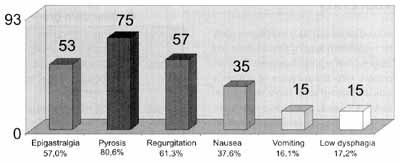

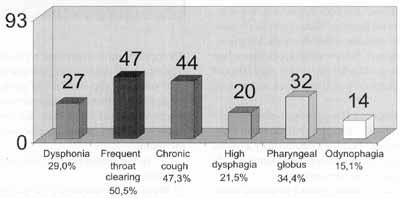

INTRODUCTIONGastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been widely studied in recent years. The understanding of this disease has changed significantly and issues concerning diagnosis deserve further investigation. There are two main types of patients: those with classic symptoms and those who have manifestations affecting the upper airways. Classic symptoms are heartburn, regurgitation and epigastralgia, in addition to other gastrointestinal manifestations, such as nausea, vomiting and lower dysphagia. Pain is present at post-prandial period (30 to 45 minutes after the meals) and it may irradiate to the ears, limbs and chest. The most frequent otorhinolaryngologic complaints are throat clearing, chronic cough, pharyngeal globus, persistent or intermittent chronic dysphonia and odynophagia4, 12, 14.

It requires thorough head and neck inspection; however, in many occasions there are no detected signs at physical exam, which is important also to exclude other diseases. Laryngoscopy is a fundamental portion of the assessment, because when examining the larynx, the otorhinolaryngologist may suspect that the larynx is being damaged by acid exposure, suspecting of GERD17.

Complementary exams most frequently used are esophageal x-rays with contrast, esophageal manometry, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. The most important exams are pH monitoring and esophagogastroduodenoscopy5.

Esophageal x-ray with contrast shows structural alterations of upper digestive tract. The objective is to identify tumor lesions or specific abnormalities that may cause the reflux, and not to quantify the degree of reflux. The presence of hiatus hernia is not as relevant as expected. Approximately one third of patients with hiatus hernia do not show evidence of gastroesophageal reflux, showing that the presence of hernia is not essential for the genesis of reflux.

As manometry, its core value is not in defining diagnosis of reflux, but rather in identifying other affections that may produce symptoms similar to the reflux. Diseases such as achalasia, esophageal diverticulum, and colangenovenous mixed diseases may be mistaken by simple reflux esophagitis.

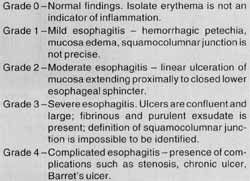

EGD, in turn, checks the mucosa of the esophagus and may present the consequences of reflux. The main finding is esophagitis, whose endoscopic graduation is presented in Chart 1. The precise location of squamocolumnar junction, presence or absence of hiatus hernia and presence or absence of erosion and ulceration are observed.

On the other hand, pH monitoring evaluates objectively and over time the presence and severity of involuntary reflux of gastric contents inside esophagus. It is considered the gold standard exam for assessment of gastroesophageal reflux3,8,15.

CHART 1 - Endoscopic grading of esophaditis.

PH monitoring is expressed by index DeMeester, a complex mathematical calculation that assesses jointly the number of acid refluxes, the number of prolonged acid refluxes, the longest acid reflux, the total time with pH lower than 4.0, time fraction with pH lower than 4.0 and correlation of all these figures and the symptoms experienced by the patient during the exam.

In the present study, we tried to answer the following questions:

1) What is the frequency of gastrointestinal and otorhinolaryngologic manifestations in GERD? In what proportion of cases there is only otorhinolaryngologic manifestations?

2) What is the accuracy of esophagogastroduodenoscopy compared to pH monitoring for diagnosis of GERD? Could EGD be used as the only diagnosis method of GERD in any situation, dispensing the use of pH monitoring?

MATERIAL AND METHODThis study was conducted at Clínica Sugisawa, in Curitiba, between November 1998 and March 2000, in which 178 patients were submitted to 24-hour pH monitoring. Patients responded a questionnaire inquiring about symptoms: 1) Gastrointestinal symptoms: epigastric pain, heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting and lower dysphagia. 2) Otorhinolaryngologic symptoms: dysphonia, frequent throat clearing, chronic cough, upper dysphagia, pharyngeal globus and odynophagia. Patients referred their symptoms in a scale of 0 to 4: 0 = absence of symptom; 1 = symptom present occasionally, but not disturbing the patient; 2 = symptom present occasionally and disturbing patients' daily activities; 3 = frequent symptom, disturbing patients` daily activities a lot; 4 = severe and disabling symptom. In order to conduct the analysis, we considered the symptoms absent if they were scored 0 or 1, and present if scored 2 to 4.

Graph 1. Frequency of gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with pathological reflux confirmed by pH monitoring.

Graph 2. Frequency of otorhinolaryngologic manifestations in patients with pathological reflux confirmed by pH monitoring.

Description of computed monitoring of intraesophaegal pH: all patients were submitted to ambulatory pH monitoring, using equipment Synetics Digitrapper MK III. An electrode of antimony pH was positioned 5cm above the upper margin of lower esophageal sphincter. Acid reflux was defined as a fall in pH below 4.0. The total duration of exams was in average 24 hours. During the study, we recorded the number of prolonged acid refluxes, the longest acid reflux, total time with pH below 4.0, the fraction of time with pH below 4.0, and the correlation of these figures and the symptoms patients experienced during the exam. These data were analyzed using index DeMeester (IDM), and the patient had pathological gastroesophageal reflux if IDM was higher than14.72.

In addition, results of EGD and direct laryngoscopy were also added to medical files for those patients who had been submitted to these exams at least 1. month before the pH monitoring.

RESULTSAges of patients varied from 21 to 82 years, mean of 43.4 years; 102 patients (57%) were female and 76 (43%) were male patients. IDM was higher than 14.72 in 93 (52%) of 178 patients submitted to pH monitoring. Symptoms presented by patients that confirmed gastroesophageal reflux-are shown in Graphs 1 and 2.

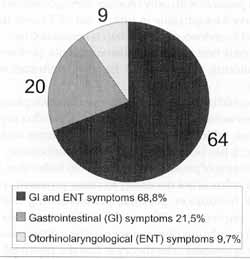

Out of 93 patients, 64 (68.8%) presented one or more gastrointestinal symptoms and one or more otorhinolaryngologic symptoms; 20 (21.5%) patients presented only gastrointestinal symptoms and 9 (9.7%) patients had only otorhinolaryngologic symptoms (Graph 3).

Graph 3. Number of patients according to referred symptoms.

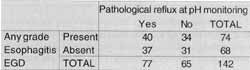

Out of 178 patients who underwent pH monitoring, 142 had been submitted to EGD one month before the exam. In the group with pathological reflux of distal esophagus (93 patients), 77 were submitted to EGD. Among them, 40 (51.9%) presented some degree of esophagitis with or without other lesions. Thirty patients (39%) presented other lesions, such as gastritis, duodenitis, hiatus hernia, etc. without esophagitis. EGD was normal in 7 (9.1%) of 77 patients with pathological reflux confirmed by pH monitoring. On the other hand, among 85 patients with IDM lower than 14.72, 65 underwent EGD and in 34 (52.3%) the exam demonstrated some degree of esophagitis, with or without other lesions; in 21(32.3%), there were other lesions, such as gastritis, duodenitis, hiatus hernia, etc. without esophagitis; and in 10 (15.4%), EGD was normal. Data collected are presented in Table 1. The endoscopy, when compared to pH monitoring, gold standard for diagnosis of GERD, had sensitivity of 52% (40/77), specificity of 48% (31/65), positive predictive value of 54% (40/74) and negative predictive value of 46% (31/68). General accuracy of EGD was 53% (74/140) for diagnosis of GERD.

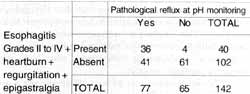

Are there situations in which pH monitoring would be considered unnecessary? Are there situations in which the combination of symptoms associated with EGD would confirm GERD? To answer these questions, we analyzed all patients who had moderate, severe and complicated esophagitis (Grades II to N according to the endoscopic classification of esophagitis, previously mentioned), plus the presence of 3 cardinal symptoms of GERD, the most frequently reported in our study heartburn, regurgitation and epigastralgia. We considered the hypothesis positive when at least 2 of these symptoms were present. Forty patients met the criteria - 36 of them had pathological reflux according to pH monitoring. Table 2 shows the results obtained. Esophagitis grades II to IV, associated with at least 2 out of 3 classic symptoms of GERD (heartburn, regurgitation and epigastralgia) had a sensitivity of 47% (36/ 77), specificity of 94% (61/65), positive predictive value of 90% (36/40) and negative predictive value of 60% (61/102) for GERD.

TABLE 1

TABLE 2

In 9 patients who had only otorhinolaryngologic symptoms, such as frequent throat clearing, chronic cough, pharyngeal glomus, etc., without gastrointestinal manifestation, seven were submitted to EGD, which was normal in 2 patients (28.57%). Two patients (28.57%) had hiatus hernia, without esophagitis. Three patients had esophagitis; in 2 cases (28.57%) grade I esophagitis (mild), and in one patient (14.29%) grade II esophagitis (moderate).

Among 93 patients with index DeMeester higher than 14.72, 16 (17%) underwent laryngoscopy. The following classification was used for laryngoscopic findings: mild laryngitis arytenoid hyperemia; moderate - significant erythema, secretion stasis and granular mucosa; and severe - ulceration, granulation tissue and hyperkeratosis (Hanson et al.7, 1995). All these patients had at least one otorhinolaryngologic manifestation, associated or not with gastrointestinal manifestations. The findings were the following:

o normal laryngoscopy - two patients (12.5%);

o mild laryngitis (arytenoid hyperemia) - 7 patients (43.75%);

o moderate posterior laryngitis - 4 patients (25°/0);

o severe posterior laryngitis - 2 patients (12.5%); and

o posterior glottic chink- one patient (6.25%).

DISCUSSIONGastrointestinal symptoms are obviously the most evident symptoms of GERD. The main complaints are heartburn, regurgitation, epigastric pain and dysphagia, as observed in the present study. However, in only 9.7% of the patients with pathological reflux at pH monitoring there were only otorhinolaryngologic symptoms. The most frequent symptoms in decreasing order were frequent throat clearing, chronic cough, globus pharyngeal, and dysphonia. It is estimated that 20 to 60% of patients with GERD have otorhinolaryngologic symptoms without heartburn or other classic symptoms (Abuja et al.2, 1999). This difference in findings between this study and the data in the literature was probably due to the small number of patients, analyzed by this study, who had only otorhinolaryngologic symptoms.

The use of ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring is not universal because not all patients have access to this exam. As a consequence, treatment to GERD is normally prescribed without a definite confirmation of the diagnosis.

The present study showed that almost all patients with Grades II to IV of esophagitis associated with at least two out of three classic symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, epigastralgia) of GERD had pathological reflux according to pH monitoring. This clinical presentation has a specificity of 94% and a positive predictive value of 90%. Based on this information, it would be possible to treat patients for GERD without conducting pH monitoring, confirming the results obtained by other authors as well (Tefera et al.16, 1997).

A potential mistake could be made with patients that developed severe heartburn, regurgitation and/or epigastralgia and moderate and complicate esophagitis secondary to medication. It may be avoided by collecting a very comprehensive patient history.

PH monitoring is still necessary in patients who have atypical symptoms, such as otorhinolaryngologic manifestations, or in cases of mild esophagitis detected by EGD, or in the presence of Grades II to IV esophagitis but without the classic symptoms of GERD.

In 48.1% of patients with pathological reflux confirmed by pH monitoring, there was no esophagitis detected at EGD. For these patients, pH monitoring was essential for the diagnosis of GERD. This result confirms the recommendation by Kahrilas and Quigley9 (1996), that pH monitoring is indicated in patients who had normal endoscopy but persistent symptoms of GERD. Reflux might be followed by esophageal mucosa irritation or inflammation, because many variables have been identified as co-factors in the pathogenesis of erosive esophagitis. We may include among them the composition of reflux, duration of exposure of susceptible mucosa and intrinsic resistance of target tissue.

In patients with only otorhinolaryngologic symptoms, we observed esophagitis in only 3 out of 7 cases that were submitted to endoscopy (42.86%), classified as Grade II (moderate) in only one patient. For these patients, performance of pH monitoring was essential for the confirmation of the diagnosis.

It could be argued that one more electrode placed on the esophagus would be necessary to detect acid reflux in proximal esophagus, which is very common in patients with GERD. However, it has been demonstrated that ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring of proximal esophagus has little value, because proximal reflux is not necessary to cause proximal symptoms of GERD. In addition, proximal pH monitoring is subject to inherent imprecision (Wo et al18, 1997). Acid exposure of proximal esophagus does not seem to be a determinant factor for these symptoms. The theory is that the proximal reflux is necessary only for the onset of some signs and symptoms. Laryngitis, for example, requires direct acid exposure in the larynx. Hypopharyngeal reflux is more common in these patients; however, proximal esophagus reflux is not. It suggests abnormalities at the level of upper esophageal sphincter enablfng hypopharyngeal reflux, but not in the proximal esophagus. In addition, the amount of acid required to damage the larynx is very small. This small quantity may not be recorded as abnormal by the exam. GERD may cause or aggravate asthma, because it causes a bronchospasm mediated by vagus nerve, without necessarily having a proximal reflux. Gastric acid microaspiration may also trigger asthma symptoms. Once again, it may not be recorded as an abnormal amount by the electrode placed at the level of upper esophageal sphincter. PH monitoring is considered gold standard test for diagnosis of GERD, but it has limitations. One limitation is imprecision in measuring duration of acid exposure to proximal esophagus. The conclusion of the authors is that the decision of offering anti-reflux treatment to patients who have hypothesis of GERD should not be based on presence or absence of proximal reflux.

Results obtained in laryngoscopy confirmed the data provided by the literature. The most common finding in GERD was arytenoid hyperemia. Posterior larynx is the most commonly affected area, probably due to position and effects of gravity. Many authors reinforced that reflux should be investigated if there is unexplained arytenoid hyperemia, chronic dysphonia or chronic cough. There is also the association of laryngeal carcinoma and gastroesophageal reflux, and subglottic laryngeal stenosis and GERD6,7,10,11,13,17.

CONCLUSIONSThe main manifestations of GERD are gastrointestinal. Out of 5 patients with GERD, four complain of heartburn and three of regurgitation or epigastric pain. These are the cardinal symptoms of GERD. The most common otorhinolaryngologic complaints in decreasing order of frequency are frequent throat clearing, chronic cough, globus pharyngeal and dysphonia. Otorhinolaryngologic manifestations without the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms occur in a proportion of 10% of patients with GERD, however we believe that this figure .is even higher because of the reasons described above.

The isolate finding of esophagitis at EGD in diagnosing GERD had an accuracy of 53%, compared to the gold standard exam - pH monitoring. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy should not, therefore, be used as the only diagnostic method for the pathology. However, if there is moderate, severe or complicated esophagitis detected at EGD, plus at least two of the three cardinal symptoms of GERD (heartburn, regurgitation, epigastralgia), pH monitoring may be dispensed because this association has specificity of 94%.

REFERENCES1. ACHEM, S. R. - Endoscopy-negative gastroesophageal reflux disease. The hypersensitive esophagus. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am., 28(4):893-904, 1999.

2. AHUJA, V.; YENCHA, M. W. & LASSEN, L. F. - Head and neck manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. Fam. Physician., 60(3):873-80, 885-6, 1999.

3. BREMNER, R. M.; BREMNER, C. G. & DEMEESTER, T. R. Gastroesophageal reflux: The use of pH monitoring. Curr. Probl. Surg., 32:429-568, 1995.

4. DEMEESTER, T. R.; BONAVINA, L.; IASCONE, C.; COURTNEY, J. V. & SKINNER, D. B. - Chronic respiratory symptoms and occult gastroesophageal reflux. Ann. Surg., 211(3):337-45, 1990.

5. DEVAULT, K. R. & CASTELL, D. O. - Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol., 94(6):1434-42, 1999.

6. GIACCHI, R. J.; SULLIVAN, D. & ROTHSTEIN, S. G. Compliance with anti-reflux therapy in patients with otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Laryngoscope, 110(1):19-22, 2000 Jan.

7. HANSON, D. G.; KAMEL, P. L. & KAHRILAS, P. J. - Outcomes of anti-reflux therapy for the treatment of chronic laryngitis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol.. 104:550-55. 1995.

8. JAMIESONJ. R.; STEIN, H. J.; DEMEESTER, T. R.; BONAVINA, L.; et. al. - Ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH monitoring: Normal values, optimal thresholds, specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 87(9):1102-11, 1992.

9. KAHRILAS, P. J.; QUIGLEY, E. M. M. - Clinical esophageal pH recording: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterol., 110:1982-96, 1996.

10. KOUFMAN, J. A. - The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope, 101(4 Pt 2 Suppl 53):1-78, 1991.

11. MCNALLY, P. R.; MAYDONOVITCH, C. L.; PROSEK, R. A.; COLLETTE, R. P. & WONG, C. R. K. H. - Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux as a cause of idiopathic hoarseness. Dig. Dis. Sci., 34:1900-4, 1989.

12. OLSON, N. R. - Laryngopharyngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am., 24(5):1201-13, 1991.

13. ORMSETH, E. J. & WONG, R. K. - Reflux laryngitis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 94(10):2812-7, 1999.

14. RICHTER, J. E. - Typical and atypical presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastrointest. Clin. North Am., 25:75-102, 1996.

15. RICHTER, J. E.; BRADLEY, L. A.; DEMEESTER, T. R. & WU, W. C. - Normal 24-hr ambulatory esophageal pH values Influence of study center, pH electrode, age, and gender. Dig. Dis. Sci., 37(6):849-56, 1992.

16. TEFERA, L.; FEIN, M.; RITTER, M. P.; et al. Can the combination of symptoms and endoscopy confirm the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease?. The Am. Surg., 63(10):9336, 1997.

17. WIENER, G. J.; KOUFMAN, J. A.; WU, W.; et al. - Chronic hoarseness secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease: documentation with 24-h ambulatory pH monitoring. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 84:1503-1508, 1989.

18. WO, J. M.; HUNTER, J. G. & WARING, J. P. - Dual-channel ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring - A useful diagnostic tool?. Dig. Dis. Sci., 42 (11): 2222-26, 1997.

* Assistant Professor of the Discipline of Clinical Surgery at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná.

** Adjunct Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná.

*** Undergraduate of School of Medicine, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná.

**** Physician and Endoscopist with Clínica Sugisawa and Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Curitiba.

***** Resident Physician of the Service of General Surgery at Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Curitiba.

Affiliation: Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Curitiba - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná.

Address for correspondence: Fernando Gortz - Rua Danilo Gomes, 759 Sb. 1 E - 81670-250 Curitiba/ PR.

Tel: (55 41) 376-5484 - Fax: (55 41) 223-7247 - E-mail: fernando_gortz@hotmail.com

Article submitted on April 13, 2000. Article accented on June 9, 2000.