INTRODUCTIONPatients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have shown increased prevalence of rhinosinusitis, both acute and chronic, the latter manifested by recurrent episodes of growing severity as a result of progression of HIV2,5,6,10,18.

Since 1993, some authors have shown through prospective studies an increase in the number of cases of rhinosinusitis in this group of patients, trying to show the most common infectious agents normally responsible for paranasal sinuses chronic alterations and recurrent episodes, as well as the correlation of non-MV infected groups and the same pathology6,10,7,12,22,24.

The main agents causing acute rhinosinusitis in HIV patients are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus viridans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and in chronic cases, the main agents are e Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and anaerobic microorganisms, in addition to the growing participation of atypical microorganisms such as Listeria monocytogens, Aspergillus, atypical mycobacterium, Mycrosporadios, Cryptosporidium and Acanthamoeba, as well as viruses (Cytomegalovirus) 25,10,18,3,9,11,14,16,23,4.

Multiple variables contribute to the results of paranasal sinuses cultures recognized as representatives of the diagnosis, from diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis per se, collection techniques of maxillary sinus material, possible differences between type of agent found .in maxillary antrum and ostioirieatal complex, transportation and conservation of collected material, mistakes in collection technique, contamination of sample and multiplicity of isolate agents, to many others8,15,17.

The literature has shown that cellular immunity in HIV patients is important for manifestation of acute rhinosinusal episodes or recurrent events, and the prevalence is higher in patients who have counts of CD4 < 200/ mm³ and presence of other opportunist diseases, contributing sometimes to progression of the case to fatal AIDS outcome5,6,10,24.

It has been observed that HIV patients present in their history the acquisition of HIV compatible with allergic chronic rhinosinusal disease, or not, and that as cellular immunity becomes compromised, acute rhinosinusitis episodes become more frequent, with hard to control recurrences17,1,19,8.

As to predisposing factors, there are no data correlating anatomical alterations or previous allergic rhinitis as determinants for manifestation of rhinosinusitis in HIV patients. The use of inhaled drugs was mentioned as a significant predisposing factor for rhinosinusitis in this group of patientsl3, 20.

There are studies that correlate high levels of IgE and delay in mucociliary motility in HIV patients as an important factor for severity of rhinosinusitis episode and its recurrence13,20.

In the only study conducted in Brazil with HIV patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, the prevalence pattern of involved microorganisms follows the one reported in the literature for acute rhinosinusitis, with predominance of Streptococcus pneumoniaeand Streptococcusviridans(28.13%). Clostridium sp., Clostridium perfringes and Peptococcus micros presented lower prevalence, similar to other microorganisms found in non-HIV infected groups with chronic rhinosinusitisl7.

The objectives of the present study were:

1. Study the positivity of cultures of sample from maxillary antrum of HIV patients with diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without recurrence.

2. Try to identify the most frequently involved microorganisms in cases of rhinosinusitis in HIV patients.

3. Contribute to empirical antimicrobial treatment used for approaching this pathology in HIV infected patients, so that it may be performed more appropriately.

MATERIAL AND METHODThe 21 HIV-infected patients that participated in our study were referred by the infectologist, and they had a previous diagnosis of rhinosinusitis and some of them were being submitted to clinical and/or preventive treatment with antibiotics against opportunist diseases. In the referral form, the data that had suggested to the general practitioner an episode of rhinosinusitis were headache without defined location, fever - sometimes the only piece of data observed - and nasal obstruction, a manifestation present in all cases even before the diagnosis of HIV was confirmed.

The patients were assessed through clinical history, physical ENT exam and radiological exam of paranasal sinuses, and the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis or chronic rhinosinusitis with recurrence was made. All patients had previous history, before HIV confirmation, suggestive of chronic rhinosinusitis.

The patients underwent puncture of the most affected maxillary sinus, based on visualization through rigid nasoendoscopy showing more radiological involvement and/or purulent secretion on ostiomeatal complex.

After explaining the reason for performing the procedure and obtaining his or her informed consent, the puncture was conducted. All of them were performed in the ambulatory, under mucosa topic anesthesia with 10% xylocaine spray and infiltration of canine fossa with 20% xylocaine, without vasoconstrictor, after oral hygiene with oral antiseptic and local hygiene with PVPI. The patient was submitted to puncture of canine fossa with appropriate trocar and when there was access to maxillary antrum a sample of local purulent secretion was collected, or if there was no purulent secretion, a lavage of the cavity with sterile solution was conducted. The material was sent to the microbiology laboratory of HCRP - FMRP in proper means (Culture Swab Transport System - DIFCO Laboratories) for aerobic, in a test tube adequate for fungi and mycobacterium culture and a means adequate for anaerobic, vacuum vial.

Owing to technical difficulties inherit to the procedure and the service, it was not possible to collect adequate material from the mucosa of maxillary antrum for biopsy or culture.

After the collection of samples, maxillary antrum was irrigated with a solution of Rifocine (500 mg) and sterile solution 0.9%, observing the output of the solution via ipsilateral nasal fossa and the jugal mucosa sutured with a stitch of 3.0 categut, followed by oral hygiene with buccal antiseptic solution and application of 24-hour action non-hormonal anti-inflammatory.

Samples were submitted to culture and identification of microbial agents, following the routine used at the laboratory of the hospital, using international standardized techniques for the procedure (Livro de Procedimentos Laboratoriais do HCFMRP-Annex I (1-18 )).

Patients who had purulent secretion at puncture were treated with different antibiotics, according to the drugs used previously and the responses obtained to them. The medication was changed 5 days later, when the definite results from culture and antibiogram were ready.

As a control group for the analysis of cultures, we selected randomly 14 patients submitted to nasal endoscopic surgery with presentation of chronic rhinosinusitis and recurrences, with samples obtained from aspiration of maxillary antrum via open ostiomeatal complex during the surgical procedure. The material was analyzed by the same microbiology laboratory.

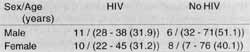

RESULTSDisposition of both groups is presented in Table 1, showing the equal distribution of sex and age in the HIV group.

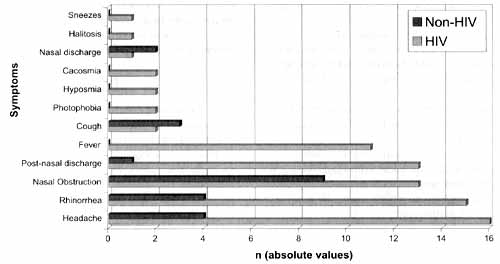

As to clinical symptoms in HIV patients, we found that the main symptom was headache (16/21), followed by rhinorrhea (15/21), post-nasal discharge (13/21), nasal obstruction (13/21) and fever (11/31); and less frequent, cacosmia, hyposmia, photophobia and cough. In the non-HIV group, we found nasal obstruction (9/14), headache (4/14), rhinorrhea (4/ 14) and cough (3/14) (Graph 1).

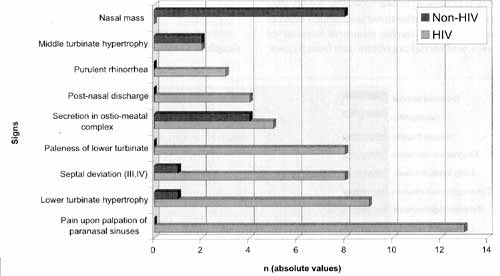

Physical exam findings showed a high level of pain upon palpation of paranasal sinuses, without specification of location (13/21), followed by inferior turbinate hypertrophy and paleness (9/21), septal deviation (8/21), ostiomeatal complex secretion (5/21) and post-nasal discharge (4/21) in the HIV group; in the non-HIV group, we observed mass in the nasal fossa as the most frequent finding (8/14), because most of the patients had nasosinusal polyposis (Graph 2).

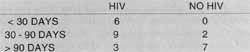

As to time of progression of rhinosinusal manifestation, in both groups, most of the subjects had a duration over 90 days, 12/21 in HIV group and 9/14 in non-HIV group, and in cases of non-HIV patients with progression time lower than 30 days, the clinical presentation represented an episode of recurrent rhinosinusitis (Table 2).

TABLE 1 - Distribution according to sex and age of groups of patients with HIV and without HIV.

TABLE 2 - Duration of evolution in days of rhinosinusal presentation in evaluated patients in groups with HIV and without HIV.

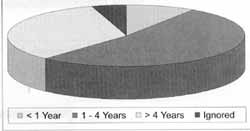

In the group of HIV patients, the estimated time for virus infection (first diagnosis) varied from 1 month to 12 years, mean of 3.5 years, and most of them had had an one-year progression and previous severe opportunist diseases (Graphs 3 and 4).

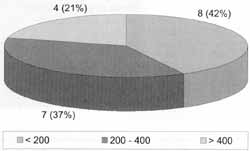

Patients who had previous severe opportunist diseases showed count of CD4 < 200 cells/mm³, specially those with neurological impairment, such as neurocriptococosis and neurotoxoplasmosis, and there was no correlation between CD4 count and presence of purulent secretion in ostiomeatal complex region; this count was present in fewer than 50% (8/ 21) of the HIV patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (Graph 5).

As to predisposing factors for development and maintenance of rhinosinusitis episodes reported in the clinical history of patients, inhalation of drugs, septal deviations and history of allergic rhinitis treated irregularly were present in the frequency of 4/21 in HIV patients, and in 17/21 of them there was previous history of chronic rhinosinusitis and recurrent rhinosinusitis, even before the diagnosis of HIV infection. Among non-HIV patients, recurrence of nasosinusal polyposis and allergic rhinitis treated irregularly were the most frequent presentations (3/14).

The lab test to support diagnosis in HIV patients ordered by the infectologist was paranasal sinuses x-ray; if required, a CT scan of the paranasal sinuses was also ordered.

In the group of HIV patients, we found opacification of maxillary sinuses in 19/21, patients with bilateral affection in 12/21, followed by opacification of frontal sinus in 9/21 and 7/ 21 in ethmoid sinuses. As to liquid level, we found 3/21 in maxillary sinuses, 1/21 in ethmoid, and 1/21 in sphenoid. We also found suggestive images of retention cyst of maxillary sinus in 2/21 patients.

Graph 1. Most frequently found symptoms in two groups that raised the suspect of chronic rhinosinusitis (in absolute values).

Graph 2. Main findings of the physical exams in the two studied groups (in absolute values)

In the non-HIV group, maxillary affection was present in 9/14 patients, followed by sphenoid sinus (5/14) and ethmoid sinus (4/14), and one patient had retention cyst (Table 3).

The results of microbiology showed absence of growth in 33.32% (7/21) of HIV patients and in 28.57% (4/14) in non-HIV ones. Two or more microorganisms were isolated in 23.80% (5/21) of HIV group and in 21.42% (3/14) of non-HIV patients, and we did not find results in 3 patients from each groups.

1. microorganism most frequently isolated in HIV patients group was Staphylococcus aureus (16.65% - 3/18), followed, in the same frequency, by Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Peptostreptococcus (11.10% - 2/ 18).

In the group of non-HIV patients, we found Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae with similar frequencies (18.18% - 2/11).

Other microorganisms found were: Clostridium perfrigens, Eubacterium lentum; Clostridium bifermendans, Mycobacterium fortuitum, streptococcus group G, Streptococcus viridans, Fusobacterium neophorum, Histoplasma capsulatumand Candida albicans.

Mycobacterium fortuitum is a atypical mycobacterium and there are no reports of this finding in paranasal sinuses of HIV patients without pulmonary affection (Table 4).

We did not made culture for fungi because of its technical complexity and difficulty to incorporate it in the routine of HCRP-FMRP.

As to empirical antimicrobial treatment, employed after the puncture, amoxicillin was the most frequently used drug (7/ 21), and recurrence was present in one case, few weeks after the treatment; three patients maintained unchanged clinical presentation, one patient died during treatment because of opportunist diseases, and we did not obtain data from 3 cases. Azithromycin was used in 3 patients who presented clinical improvement in 2 days, and one of them had recurrence. Clyndamycin was used in 2 patients with clinical improvement presented in 2 cases, 48 hours after the begin of treatment.

DISCUSSIONBacteriology of chronic rhinosinusitis in adult patients without immunological affection is a very controversial topic. Hsu et al. (1998) found out of a total of 48 cultures, 43 positive samples with the highest frequency of negative staphylococcus coagulase (28%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17%) and Staphylococcus aureus (13%), showing high levels of antimicrobial resistance to them8.

Graph 3. Duration of progression of HIV infection (in years).

Graph 4. Opportunist diseases and previous chronic diseases in tile two studied groups (in absolute values).

TABLE 3 - Radiological alterations found in paranasal sinuses x-ray of HIV patients and in CT scans of non-HIV patients.

Nadel et al. (1998), in samples obtained via endonasal, guided by endoscope, found negative coagulase staphylococcus in 29.5% of cultures, Staphylococcus aureus in 19.8%, Streptococcus pneumoniae in 11.6% and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 14.6 %15.

In a study conducted in Brazil, Oliveira (1996) found Streptococcus vhldans in 30.43% of cultures, followed by Staphylococcus aureus in 13.04% and Haemophilus influenzae in 8.69%17.

In our study, in the group of non-HIV patients with history of chronic rhinosinusitis, we found Pseudomonas aeruginosa together with Klebsiella pneumoniae in 18.18% of cultures and Staphylococcus aureus in 9.09%. Despite the fact that the analyzed sample was small, we found rates similar to the literature, but showing disagreements specially regarding positivity of Staphylococcus aureus, comparing cultures from maxillary sinus puncture via canine fossa and other cultures obtained via endoscope, which may reach higher rates of vestibular contamination. It differs from Nadel et al. (1998)15, who proposed that all samples collected via endonasal access be representative of ostiomeatal complex, originated not only from the maxillary sinus but also from frontal sinus and anterior ethmoid cells.

As to HIV patients with diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis, Tami (1995) found a higher prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, followed by Staphylococcusaureusand anaerobic bacteria21.

In a review article, DeShazo and Wald (1998) reported in decreasing order the frequency of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, group D streptococcus, as well as the presence of fungi and viruses, as a rare cause, but something that would cause chronic infection of paranasal sinuses of patients infected by HIV2.

Graph 5. Count of cells CD4 in HIV infected patients with episodes of chronic or recurrent rhinosinusitis (cells / mm³).

Oliveira (1996) showed the presence of Streptococcus pneumonea and Streptococcus viridansin 25.71% of samples of HIV patients, followed by negative coagulase staphylococcus (17.14%)17.

In our study, in the group of HIV patients, we found a higher frequency of Staphylococcusaureus(16.65%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (11.10%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (11.10%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5.55°%) and anaerobic agents in 33.39%. We found fungi in 11.10% of the cases and group D streptococcus in 5.55%. Such results are in accordance with what is described in the literature, showing high rates of aerobic, gram positive coccus, resulting in the important presence of anaerobic agents. The presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was not as evidenced as suggested by Zurlo et al. (1992), O'Donnell et al. (1993) and Grant (1993), as an important ascending pathogen as a cause of chronic rhinosinusitis and recurrence in HIV patients6,24,16.

TABLE 4 - Results of microbiological culture for aerobic and anaerobic agents, fungi and mycobacterium, in absolute values.

Comparing the studied groups, HIV and non-HIV infected patients who had diagnosis of chronic and recurrent rhinosinusitis, we did not find agreement in the two groups: in HIV patients there was a predominance of gram positive coccus and anaerobic, and in non-infected patients there was predominance of gram negative bacilli, followed by anaerobic agents. Such findings may be explained by the fact that in HIV infected patients the presence of recurrent rhinosinusitis is frequent, and there is also the trend of having a similar behavior of acute rhinosinusitis in HIV patients, as shown by DeShazo and Wald (1998) and Milgrim et al. (1994)2,12.

High levels of negativity reported by Milgrim et al. (1994), Tami (1995), Oliveira (1996), Nadel et al. (1998) and Hsu et al. (1998), noticed also in our study, may reaffirm the considerations of Gwaltney et al. (1992), who showed in a review article that chronic rhinosinusal disease represents a chronic damage to the mucosa, impairing its sterility status, and emphasizing the process of mucosa structural lesion, predis posing to bacterial sinusal infection. To Milgrim et al. (1995), abnormality in mucociliary clearance in HIV patients with chronic rhinosinusitis may be irreversible, and if associated with nasal obstruction, it represents the most important recurrence mechanism in this population12,8,15,17,21,13.

The paranasal sinus could be structurally affected with visible chronic radiological abnormalities, but still not present an infection phase or have a viral infection, especially viruses that affect upper respiratory tract, which may be a predisposing factor for secondary sinusal bacterial infection. In our study, we could not assess incidence of virus in paranasal sinuses, because of technical difficulties and financial restraints'. Another justification for low rate of positivity in the sample is previous use of antibiotics, both preventive and therapeutic in these two groups of patients; interruption of medication for the conduction of the study would not have been an ethical attitude.

In the group of HIV patients, Upadhyay et al. (1995), Marks et al. (1998) and DeShazo and Wald (1998) reported infection by cytomegalovirus, something that has been growing significantly in this population. However, we should bear in mind that this is a causing agent of opportunist diseases that affect other organs, and it may be present in the paranasal sinuses as structurally affected, but without causing their infection2, 11,23.

Concerning the presence of fungi, Upadhyay et al. (1995), Dunand et al. (1997) and DeShazo and Wald (1998) showed the importance of considering such agents as failure in antimicrobial treatment; in our study, we found two cases of HIV patients who had Candida albicans manifested as extensive esophageal candidiasis, and another case with Histoplasma capsulatum, but the patient had already experienced pulmonary histoplasmosis. Such findings seem to favor the hypothesis that immuno suppresion condition favors emergency of such microorganisms as a cause of chronic and recurrent rhinosinusitis, especially if the patient has affection of other organs by the same agents, such as the aerodigestive tract23,4,17.

Comparing the groups of HIV patients and non-infected HIV patients, we did not find statistically significant difference between negativity findings and isolated agents, reaffirming that there is no difference among bacterial agents that are potential causes of rhinosinusitis in patients with or without HIV, justifying maintenance of empirical treatment suggested for infectious rhinosinusitis in patients without immunological affection; in addition, we should always remember the possibility of gram negative bacteria, specially Pseudomonas aeruginosa and anaerobic agents in failure of first choice antibiotics.

As to signs and symptoms of rhinosinusitis in HIV patients group there was no significant predominance of alterations that could direct diagnosis of rhinosinusitis, but rather the presence of general symptoms that were not specific. Headache was the most frequent symptom reported, and it may not be considered an objective indicator, because most of the patients did not report a precise location of symptom, and the majority also had central nervous system affection because of opportunist diseases common in HIV patients.

Rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction and post-nasal discharge were also frequent but are not specific for sinusal disease. Fever was a common finding in HIV patients, but there was no correlation between it and the presence of secretion in paranasal sinuses or positivity of culture; moreover, the patients had opportunist diseases that caused fever. Reports in the literature warned of the fact that acute and recurrent rhinosinusitis may cause fever of undetermined origin in patients with HIV, but we could not confirm that in our study.

Godofsky et al. (1992) and Zurlo et al. (1992) demonstrated that count of cells CD4 < 200 cells/mm³ was important for the extension and severity of rhinosinusitis in HIV patients, as well as to resistance to antimicrobial treatment. In our study, we found such count in 42% of the patients and they did not have higher levels of positive results in cultures, presence of fever or purulent secretion in the paranasal sinuses, but they all represented the presence of opportunist diseases being specifically treated. However, we could not evaluate if the patients had failed in antibacterial treatment5,24.

Findings of simple x-ray of paranasal sinuses showed most frequent presence of opacification in maxillary sinuses, a non-specific and little conclusive finding of the real situation of sinusal affection. There was no relation between radiological signs of liquid level in examined maxillary sinuses; such a situation could have been justified by the fact that the patients had been referred to conduct puncture of paranasal sinuses, many of them already making use of preventive or therapeutic antibiotics.

As to therapy used, empirical therapeutic mode was the most widely used, specially with the use of amoxicillin; despite the fact that we did not obtain an adequate post-treatment assessment, the data suggested a trend towards a failure of first choice antimicrobial treatment for rhinosinusitis. Most of the patients had already taken medication in previous rhinosinusitis episodes, and in all these cases with positive cultures, the antibiogram showed resistance to amoxicillin and other penicillin preparations. In this group of patients, we should consider that the episodes are of recurrent rhinosinusitis, and therefore, second choice antibiotics for treatment of rhinosinusitis should be considered. Controlled studies aiming at this issue should be carried out in patients without immunological compromise, as well as in HIV patients, because a simple rhinosinusal episode may complicate the set of infectious pathologies that affect these subjects, resulting in earlier death.

CONCLUSIONSo Positivity to fungi was low and we isolated Mycobacterium fortuitum, an agent not found in the literature as cause of rhinosinusitis. Therefore, we should always be attentive to the possibility of paranasal sinuses affection by atypical bacteria and fungi when treating HIV patients with recurrent rhinosinusitis.

o The presence of bacteria; fungi or virus in paranasal sinuses of HIV patients or patients without immunological compromise may represent their contamination, predisposed by mucosa structural alterations, which may be an agent contributing to increased structural damage.

o Empirical treatment for rhinosinusitis in HIV patients is valid and we should bear in mind that these patients have episodes of recurrent rhinosinusitis and that second choice antibiotics should be considered for their treatment.

REFERENCES1. ARMSTRONG, M. JR.; McARTHUR, J. C.; ZINREICH, S. J. Radiographic Imaging of Sinusitis in HIV Infection. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 108(1): 36-43; 1993.

2. DE SHAZO, R. D. - Sinusitis Symposium. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences., 316(1): 1 - 45, 1998.

3. DROPULIC, L. K., LESLIE, J. M.; ELDRED, L. J.; ZENILMAN, J.; SEARS, C. L. - Clinical Manifestations and Risk Factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Patients with AIDS. J. Infect. Dis., 1995; 171: 930-7.

4. DUNAND, V. A. et al. -Parasitic Sinusitis and Otitis in Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Report of Five Cases and Review. Clin. Infect Dis., 25(2): 267-72; 1997.

5. GODOFSKY, E. W.; ZINREICH, J.; ARMSTRONG, M.; LESLIE, J. M.; WEIKEL, C. S. -Sinusitis in HIV-Infected Patients: A Clinical and Radiographic Review. Am. J. Med., 93(2): 163-70; 1992.

6. GRANT, A.; SCHOENBERG, M. V.; GRANT, H. R.; MILLER, R. F. - Paranasal Sinus Disease in HIV Antibody Positive Patients. Genitourium Med., 69: 208-212, 1993.

7. GWALTINEY, J. M. JR.; SCHEID, W. M.; SANDE, M. A.; SYDNER A. -The Microbial Etiology and Antimicrobial Therapy of Adults With Acute Community Acquired Sinusitis. A Fifteen Year Experience at the University of Virginia and Review of Other selected Studies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 1992; 90s; 457-61.

8. HSU, J.; LANZA, D. C.; KENNEDY, D. W. - Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacterial Chronic Sinusitis. Am. J. Rhinology., 1998; 12: 243-248.

9. JOSEPHSON, G. D.; SARLIN, J.; PINCUS, R. - Microsporidial Rhinosinusitis: Is this the Next Pathogen to Infect the Sinuses of the Immunocompromised Host? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 114(1): 137-9; 1996.

10. LACASSIN, F.; LONGUET, P.; PERRONNE C.; LEPORT, C.; GEHANNO, P.; VILDÉ. J. L.-Infectious Sinusitis in HIV Infection. Clinical and Therapeutic Data on 20 Patients. Presse Med., 22(19): 899-902; 1993.

11. MARKS, S. C.; UPADHYAY, S.; CRANE, L. - Cytomegalovirus Sinusitis. A New Manifestation of AIDS. Arch Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 122(7): 789-91; 1996.

12. MILGRIM, L. M.; RUBIN; J. S.; ROSENSTREICH, D. L.; SMALL, C. B. - Sinusitis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Typical and Atypical Organisms. J. Otolaryngol., 23(6): 450-3; 1994.

13. MILGRIM, L. M.; RUBIN, J. S.; SMALL, C. B. - Mucociliary Clearance Abnormalities in the HIV-Infected Patient: A Precursor to Acute Sinusitis. Laryngoscope, 105(1): 1202-8; 1995.

14. MOSS, R. B.; BEAUDET, L. M.; WENIG, B. M.; NELSON, A. M.; FIRPO, A.; PUNJA, U.; SCOTT, T. S.; KALINER, M. A. Microsporidium Associated Sinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J., 76(2): 95-101, 1997.

15. NADEL, D. M.; LANZA, D. C.; KENNEDY, D. W. Endoscopically Guided Cultures in Chronic Sinusitis. Am. J Rhinology, 1998;12: 233-241.

16. O'DONNELL, J. G.; SORBELLO, A. F.; CONDOWCI, D. V.; BURNISH, M. J. - Sinusitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis., 1993; 16: 404-6.

17. OLIVEIRA, S. B. - Sinusite Crônica em Pacientes com a Síndrome da Imunodeficiência Adquirida: Uma Avaliação Clínica, Laboratorial, Tomográfica e Microbiológica. Tese de Doutorado da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo; 1996.

18. RUBIN, J. S.; HOWINGBELG, R. H. - Sinusitis in Patients With the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J., 69: 460-3, 1990.

19. SLAVIT, D. H. - Chronic Sinusitis and Dyspnea: Could this Be AIDS? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 1990, 103: 650-2.

20.MALL, C. B.; KAUFMAN, A. ARMENAKA, M.; ROSEINSTREICH, D. L. - Sinusitis and Atopy in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis., 167(2): 28390; 1993.

21. TAMI, T. A. - The Management of Sinusitis in Patients Infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Ear Nose Throat J., 74(5): 360 - 3; 1995.

22. TSI, L.; GALVEZ, A.; BROTO, J.; GARCIA, R. E.; GUAL, J. - Sinusitis en Infección por VIH.Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp., 45(4): 301-2; 1994.

23. UPADHYAY, S.; MARKS, S. C.; CRANE, L. R.; COHN, A. M. - Bacteriology of Sinusitis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Positive Patients: Implications for Management. Laryngoscope. 105(10): 1058-60: 1995.

24. ZURLO, J. J.; FUERSTEIN, I. M.; LEBOVICS, R.; LANE, H. C. - Sinusitis in HIV-1 Infection. Am. J. Med., 93(2):157-62; 1992.

* Resident Physician in the Area of Otorhinolaryngology at Department of Ophthalmology and Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - USP.

** Ph.D. and Professor in the Area of otorhinolaryngology at the Department of Ophthalmology and Otorhinolaryngology, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - USP.

*** Ph.D. and Professor of the Area of Infectious Diseases at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - USP.

This study was awarded Best Poster at Congresso Triológico de São Paulo, module of Rhinology.

Address for correspondence: Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - USP. Departamento de Oftalmologia a Otorrinolaringologia.

Avenida Bandeirantes, 3900 - Campus Universitário - 14049-900 Monte Alegre - Ribeirão Preto /SP.

Article submitted on March 23, 2000. Article accepted on June 1, 2000.