INTRODUCTIONDiagnosis of fungal sinusitis has increased all over the world. This fact is due to new treatment approaches of neoplasic and chronic diseases. Immunodeficiency seems to provide in most situations a fertile ground for growth of different kinds of fungi. They may vary according to geographical region, but the most frequent one is Aspergillus sp (Kameswaran, 1992).

It is interesting to observe the evolution of this case of right pansinusitis with invasive characteristics and slow growth, because it is a rare affection. Fungal sinusitis may be a mild affection, a severe invasive case, or even evolve into sudden death. Past and present clinical history, CT Scan findings and intraoperative detection of friable mass that occupied the complete sinuses unilaterally confirmed the suspicion of fungal sinusitis, despite the fact that we did not isolate the fungus. Identification of fungus and lab confirmation are not possible in all cases.

LITERATURE REVIEWFungal sinusitis affects preferably compromised patients from an immunological standpoint, such as patients with diabetes mellitus, users of corticosteroids, alcohol and drugs (nasal use of cocaine seem to favor the entry of fungi), AIDS patients and those submitted to chemotherapy. In cases of bone marrow transplant, both in adults and in children, chemotherapy results in mild to severe agranulocytosis, making the patients more susceptible to fungal diseases (Wiatrak, 1991).

Current incidence of fungal sinusitis corresponds to 16% of chronic sinusitis, according to Aranzábal et al. (1996). Statistics show an increase in incidence, what can be attributed to new therapeutic approaches in severe patients and to the larger number of diagnosis performed. Chronic sinusites that are generally unilateral and do not improve with conventional treatment have to be carefully investigated with nasal endoscopy and radioimaging.

At CT Scan and sometimes at simple x-rays we can observe heterogeneous opacification with microcalcifications or homogenous opacification with bone lysis (Klossek et al, 1997). Other CT Scan findings that suggest fungal sinusitis are: unilateral lesion of one or more sinuses, mucoperiostal thickness, focal areas of bone destruction and very dense intrasinusal concretions (Pinto Leite et al., 1992). Chang et al. (1992) followed-up 13 cases of aspergillosis affecting the paranasal sinuses and they found calcification in 9 cases. In most of the cases the adjacent bone structure showed areas of erosion and sclerosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging helps diagnosis and it will become more effective as we acquire more experience in this kind of pathology.

Fungal sinusitis may present an infectious picture, normally caused by Aspergillus sp limited to the affected paranasal sinus (non-invasive form), and also destroy the wall of the sinus with or without tissue invasion (semi-invasive form) (Aranzabal et al., 1996).

According to Carpentier et al. (1994), non-invasive form may be divided into two subgroups: localized and allergic and invasive, that may be divided into indolent (slow progression) or sudden. Fungal sinusitis may affect immunocompetent or immunodepressed subjects. People belonging to the former group are more affected by non-invasive fungal sinusitis, whereas those that belong to the latter are victims of more severe episodes of fungal sinusitis.

Non-invasive fungal sinusitis (extra mucosa and nonallergic) corresponds to fungus ball, aspergilloma ball or mycetoma, a bundle of fungi hyphae with minimal tissue reaction (Manning et al., 1991). Prognosis is highly favorable and in our environment it affects mainly the following sinus in decreasing order, according to Pereira et al. (1997): maxillary, sphenoid, ethmoid and frontal. Chang et al. (1992) found 6 patients with fungus ball and seven with tissue invasion, out of a total of 13 cases.

Allergic extramucous fungal sinusitis is characterized by the presence of allergic mucus that comprises necrotic inflammatory cells, Charcot-Leyden crystals and sparse fungi, involved by an intense mucosa reaction without tissue invasion. In many cases, there is a correlation between allergic sinusitis and allergic pulmonary aspergillosis (Manning et al., 1997). They are normally patients without history of diabetes or cancer who have chronic nasal obstruction with polypoid mucosa or nasal polyposis. We may also frequently detect bone erosion with intraorbital or intracranial extension, when patients have headache, proptosis, and less frequently, amaurosis.

Daghistani et al. (1992) published 5 cases of fungal sinusitis by Aspergillus sp with proptosis and signs of allergic rhinitis. Histologically, lesions contained eosinophils, CharcotLeyden crystals and fungi with septated hyphae. There was growth of Aspergillus fumigatus in all cases. These authors highlighted the likelihood of recurrence, development of proptosis and similar malignant tumor.

The patients may be submitted to endoscopic or open surgery. The material may be dark-colored, sticky and thick, involved by intensely inflamed mucosa (Manning et al.,1997). The most widely accepted pathogenic mechanism for allergic fungal- sinusitis is hypersensitivity mediated by IgG and IgE of fungi Aspergillus and Dematiaceous.

Post-operatively, we do not use anti-fungal medication, but corticoids (Manning et al., 1997). It is very important to have close and prolonged follow-up of patients (De Carpentier et al., 1994) and to advise them about humidity and maintenance of a very airy home environment.

Histological exam will show ramified and segmented fungi within slides of degenerated inflammatory cells. In cultures, we found fungi of different families and high percentages of false positives and negatives (Aranzábal et al., 1996).

The group of invasive mycosis, as the name goes, is more aggressive. It destroys the wall of the sinus, exposes the neighboring structures, such the orbit and the meninges, but does not invade them. For this reason, we could also classify it as semi-invasive or indolent invasive.

Generally speaking, sudden invasive infection affecting immunodepressed patients is caused by fungus of the gender Mucor (Cundari et as., 1987) and in many occasions the initial presentation simulates a nasal neoplasia, because of its angio-invasion of fungi. However, there are cases of aspergillosis with similar characteristics, causing rhino-sinus-orbital invasion with loss of sight and, sometimes, even death (Mauriello et al., 1995).

As to diagnosis, pre-operative radioimaging analysis can show more suggestive signs of the disease, even though they are not pathognomonic. Stamberger et al. (1993) identified images of metallic density in 46% of the cases, out of a total of 48 patients with fungal sinusitis. This finding is considered by many authors as caused by Aspergillus sp, and this denser image is attributed to the presence of sulfate or calcium phosphate and heavy metal salts, such as cadmium, deposited on the necrotic area of the mycetoma.

Another radiological aspect found in fungal sinusitis is the erosion of the walls, which is not caused by bone invasion of fungi, but rather by the expansion of the chronic inflammatory process, which remodels the sinus cavities and causes bone absorption (Neves-Pinto et al., 1990).

The final diagnosis is only defined if the fungus is present in a special mean, such as Sabouraud and agar glucose; however, if there is bacterial contamination, the result may be negative. Another possibility is poor collection of material. If this procedure is not performed with criteria, most probably the result will be faulty. Even in cases in which the collection is appropriate and experienced labs carry out the analysis, the result may be negative in confirmed cases of fungal sinusitis. Pereira et al. (1997) found negative cultures in 7 out of 15 patients who had fungal sinusitis diagnosed by the association of radiological findings and fungi present in direct exam.

Microbiological exam of secretions may reveal the presence of septated hypha, ramified and suggestive of hyalohyphomycosis. Among them, Aspergillus is the most frequent. Direct immunofluorescence will be in the future a very useful exam for confirmation of diagnosis. Anatomical pathologic exam with specific coloration, such as Grocot (method that enables visualization even when there are rare hyphae and it uses silver metanamine), Gridley, Pas or potassium hydroxide, reveals chronic inflammation with suppurative and/or allergic characteristics: sometimes, it also reveals fungal invasion.

Treatment of fungal sinusitis is always surgical and the approach may be either endoscopic or open (classical technique, also called conventional) or sometimes both in the same patient. The key point is that the surgeon should definitely remove all the fungal inflammatory process, according to what was previously planned.

The degree of difficulty for the exeresis of mycotic sinusitis increases from non-invasive to invasive types. In addition, there is worse prognosis. The simplest form is the aspergilloma that does not require clinical adjuvant treatment, and the most severe one is the sudden type, which is rapidly progressive.

As to therapeutic post-surgical complement, it varies according to the author. The use of systemic or topic corticoids and anti-fungal, such as anfotericine or itraconazol, will be indicated, respectively, according to the diagnosis of allergy or non-allergic invasion.

Another key point in the post-operative period concerns the environment. Wetter places are more prone to have fungal growth. Most of the infections penetrate through the respiratory access and Aspergillus sp is the main agent. The spices Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus niger are prevalent in the atmosphere and are saprophytes, normally occupying putrefying material or the soil. They use skin or mucosa abnormalities to enter the body and grow slowly during months or years (Pereira et al., 1997).

Nasosinusal fungal infection does not generally have an aggressive behavior, but it may affect the skull base through the foramens and cause bone destruction and evolve into an intra, extra or epidural abscess. Chang et al. (1997) showed a case of right temporal lobe abscess with facial pain, loss of sight, right hearing loss and compromise of cranial nerves III, IV and VI, because of allergic fungal pansinusitis by Aspergillus sp.

In addition to Aspergillus sp, there are also other spices that have been considered pathogenic to men causing nasosinusal affections. They are Candida sp, Mucor sp, Alternaria sp, Cladosporidium sp, Penicilliuim sp a Fusarlum sp. The commitment of paranasals sinuses is less common than pulmonary affection (Cedina et al., 1996). In the surgical treatment of fungal sinusitis, drainage and airing of paranasal cavities are essential to preserve their normal condition. The area should be airy and free of materials that could favor the growth of fungi.

CASE REPORTMATM, women, aged 44 years old, from São Paulo.

She reported right nasal obstruction for two years followed by thick rhinorrhea and protrusion of right eye. She had pain in the right eye, reduction of visual field, headache, foul nasal odor, anosmia, modification of taste and ear fullness on the right.

She had been submitted to mastectomy with axillary emptying four years before and radio and chemotherapy treatment. She also took hormone replacement therapy (menopause).

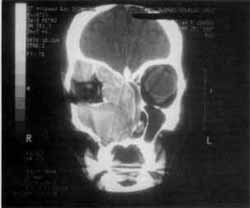

Figure 1. CT scan at coronal section showing the expansive process formed by solid homogenous tissue that occupied all paranasal sinuses on the right and the homolateral nasal fossa.

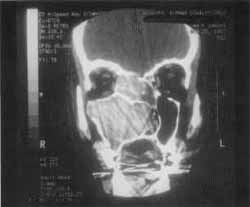

Figure 2. CT scan at axial section showing maxillary sinuses filled with solid tissue and thin walls, pushing the nasal septum to the opposite side.

At ENT exam, she had a polyp in the middle meatus that blocked completely the right nasal fossa and thick secretion of foul odor, abundant and placed on the floor of the right nasal fossa. Right proptosis was significant, the eyeball was deviated outwards and downwards with great tension.

At CT Scan, we noticed the presence of expansive process formed by solid homogenous tissue, occupying the entire right maxillary sinus, as well as the nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus, frontal-ethmoid recess and frontal sinus on the same side (Figure 1). The walls of maxillary sinus were very thin and had signs of bone remodeling on the walls of nasal fossa and ethmoid labyrinth (Figure 2).

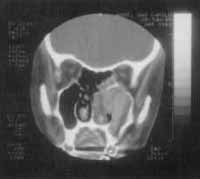

We also detected the solution of continuity of middle line ethmoid fovea on the right and crista galli apophysis, where we could visualize the process of the upper level of the cranium, close to cribiform lamina (Figure 3).

The same tissue occupied also the sphenoid sinuses and had signs of bone remodeling (Figure 4) and destruction of upper-inner orbital contour, causing proptosis that was limited by the periorbit.

There was obstruction of right lachrymal path and destruction of lachrymal-nasal duct walls.

Based on these data, the patient was referred to surgery with possible diagnosis of benign tumor or invasive fungal sinusitis.

The patient was submitted to surgery through transfacial access, with an incision of right middle-labial lateral rhinotomy with supra-orbital prolongation, associated with sub-labial.

Right after exposure of right jugal region, we observed the erosion of the anterior and medial bone wall of maxillary sinus, completely occupied by a gray friable mass, of foul smell, that occupied ethmoid cells as well and destroyed the medial wall of the orbit and the floor of the corresponding frontal sinus. There was exposure of the meninx of anterior fossa, which was in good condition and placed right above the roof of the ethmoid. We also observed a thin mucosa that seemed like pseudo-cyst on the lateral-superior wall of maxillary sinus, right after the removal of the complete mass.

Sphenoid sinus was completely taken by the mass, showing destruction of anterior and inferior walls and intersinusal septum.

In the nasal cavity, there was polypoid mass, adhered to the middle meatus, at the ostiomeatal level.

Frontal sinus was also completely occupied with the mass, showing the same aspect and moving laterally, what hindered its removal.

Bone walls that surrounded the orbits were nearly destroyed, and only the inferior one was left. Therefore, the whole mass was compressing the orbital and resulting in significant proptosis.

After cleaning all cavities, we washed them intensely with saline solution and performed incision sutures in planes.

The polypoid-like material was sent to anatomical pathological analysis that revealed non-specific chronic process and part of the mass was sent to bacterial analysis and culture, which did not show the presence of bacteria or fungi.

Figure 3. CT scan at coronal section showing the solution of continuity on the region of right ethmoid fovea.

Figure 4. CT scan at coronal section showing remodeling of sphenoid sinus walls and bone erosion.

The patient was followed in the ambulatory, showing good evolution and taking anti-mycotic therapy (itraconazol). CT scan and MRI controls, carried out one year after the surgery, revealed the presence of hyperdense recurrent lesion, homogeneous highlight and slight iodine contrast, occupying posterior-upper nasal fossa, sphenoid sinus and right ethmoid cells, extended to sellar region (Figures 5 and 6).

After the surgery arid the clinical treatment the patient remained asymptomatic and because of that decided to postpone the second surgery. One year after the x-ray control she suddenly experienced neurological symptoms, with speech compromise and right side motor deficit. MRI carried out then revealed a nodular lesion of 6.5cm, heterogeneous, and moderate effect of the mass on the left parietal-temporal region, showing characteristics of intra-parenchymatous hemorrhage.

We suspected of fungal embolus (Figure 7) and she was submitted to aspiration punch by stereotaxic craniotomy. The material was sent to anatomical pathological analysis and culture for fungi and we did not detect either tumor or the presence of fungi.

The patient was submitted also to endoscopic surgery of nasosinusal region. The material was sent to analysis and no fungi growth was evidenced.

Control MRI studies revealed that the operated region on the middle level of the face was free of the disease (Figure 8 and 9).

The patient was discharged and seemed to have improved significantly, but she still had some neurological deficit. We prescribed the use of anti-mycotic drugs and strict ambulatory control. After an eight-month follow-up, the patients was well and seemed to have recovered completely from the neurological deficit.

DISCUSSIONThe patient had a suggestive case of sinusitis with symptoms of headache, nasal obstruction, mucus-purulent rhinorrhea, sometimes mucus-bleeding secretion on the right; a CT Scan carried out 2 years before had showed small lesion, restricted to right maxillary antrum and ostiomeatal region (Figure 10). During inspection, we noted significantly large right proptosis and foul smell from the nasal fossa. According to several authors, such as Chang et al. (1992), these are the main symptoms referred by patients who have fungal sinusitis. At right rhinoscopy, we observed large polypoid mass, which after the removal, proved to be non-infiltrate and seemed to originate from the ostiomeatal complex.

The investigation of skin sensitivity on hemifaces showed normal result, what favored benign lesions. CT Scan revealed the presence of a mass that occupied all sinuses on the right and led to bone erosion of various structures; however, the tumor growth was more compressive than infiltrate.

The diagnosis of fungal sinusitis was evidence only during the operation, when we found a mass "peanut butter" type, of strong odor. Up to that moment, we still persisted with the differential diagnosis of tumor with malignant degeneration.

After one year, there was recurrence, which is very frequent in cases of invasive fungal sinusitis, but the resistance the patient had to be submitted to a second surgical procedure led to the development of fungal embolus. It was probably originated from the fungal mass that remained in the sphenoid and right sellar regions.

Figure 5 and 6. CT and MRI at coronal sections showing recurrence of the lesion in the sphenoid sinus.

Figure 7. MRI showing temporal-parietal abscess originated from com fungal metastases of compromised sinuses.

The abscess compromised the temporal-parietal area at great extend. This complication, secondary to fungal sinusitis, is very rare and had been reported only once in the literature (Chang et al., 1977). In the literature, there are few cases of fungal abscess of fungal sinusitis, associated with major health compromise and abscesses in other organs, normally in patients at intensive care units or transplanted patients who are severely immunodepressed.

Thanks to stereotaxic neurosurgery, it was possible to aspirate the abscess and reestablish the motor function of right lower limbs and speech. At the same surgical moment, we performed a second endoscopic intervention, freeing the patient from the affection, at least for a while, according to CT scan controls.

CONCLUSIONBased on clinical, radiological and surgical data, together with the evolution of the disease and the development of recurrence, we are convinced that it was a case of fungal sinusitis, classified as progressive indolent.

We believe that cases of mycotic sinusitis are increasing because of current facts, such as long-term therapies with large spectrum antibiotics and corticoids and the increased number of immunodepressed patients, such as AIDS or transplanted patients.

The study of this case, followed by the review of literature that included the latest articles, gives us the impression that fungal sinusitis is more frequent than we think and it calls our attention for the importance of carefully collecting material in order to try to identify, through lab resources, the fungus responsible for this affection. After diagnosis and treatment of patients, it is essential to conduct a constant and prolonged follow-up because recurrence is frequent, especially in cases of invasive fungal sinusitis.

Figure 8 and 9. CT scan at axial section showing that there were no signs of recurrence after the last surgical procedure.

Figure 10. CT scan at coronal section showing the lesion two years before.

1. ARANZÁBAL, L. M.; RIVAS SALAS, A.; RODRIGUES GARCIA, L.; ABREGO, O. M.; GOROSTIAGA, A. F.; ALGABA QUIMERA, J. - Aspergillosis de seno maxilar. A propósito de un caso. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp., 47 (4): 321-4, 1996

2. CEDINA, C.; MURAO, M. S.; BARBOSA, E. F. - Sinusite micótica: suspeita diagnóstica a conduta. terapêutica. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringologia, 62 (6): 484-90, 1996.

3. CHANG, C. Z.; HWANG, S. L.; a HOWNG S. L. -Allergic fungal sinusitis with intracranial abscess: a case report and literature review. Kao Hsiung Hsueh Ko Hsueh Tsa Chih, 13 (11): 6859, 1977.

4. CHANG, T.; TENG, M. M.; LI, W. Y.; CHENG, C. C.; LIANG, J. F. - Aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses. Neuroradiology, 341(6): 520-3, 1992.

5. CUNDARI, M. C.; CAMPANA, D. R.; CEDIN, A. C.; GASEL, J. J.; IRIYA, Y. - Mucormicose Rino-orbito-cerebral. Apresentação de 1 caso. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringologia, 53(3): 96-101,1987.

6. DAGHISTANI, K. J.; JAMAL, T. S.; ZAHER, S.; NASSIF, O. I. - Allergic Aspergillus sinusitis with proptosis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 106(9): 799-803, 1992

7. DE CARPENTIERJ. P.; RAMAMURTHY, L.; DENNING, D. W.; TAYLOR, P. H. -An algorithm approach to Aspergillus sinusitis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 108 (4): 314-8, 1994.

8. KAMESWARAN, M.; AL., WADEI, A.; KHURANA, P.; OKAFUR, B. C. - Rhinocerebral aspergillosis. J. Laryngol. Otol., 106(11): 981-5, 1992.

9. KLOSSEK, J. M.; SERRANO, E.; PILOQUIN, L.; PERCODANI, J.; FONTANEL, J. P.; PESSEY, J. J. - Functional endoscopic sinus surgery and 109 mycetomas of paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope, 107 (1):112-7, 1997.

10. MANNING, S. C.; MERTAL, M.; KRIESEL, K. - Computed tomography and magnetic resonance. Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Laryngoscope, 107 170-6, 1997.

11. MAURIELLO JA, JR.; YEPEZ, N.; MOSTAFARI, R.; BAROFSKY, J.; KAPILA, R.; BAREDES, S.; NORRIS, J. - Invasive rhino sino orbital aspergillosis with precipitous visual loss. Can. J. Ophtalmol., 30 (3): 124-30, 1995.

12. NEVES-PINTO, R. M.; SARAIVA, M. J.; TORRES, R. R. G.; SANTOS, S. G. - Destruição óssea a sinusite fúngica. A Folha Médica, 101:327-31. 1990.

13. PEREIRA, E. A.; STOLZ, D. P.; PALOMBINI, B. C.; SEVERO, L. C. - Atualização em sinusite fúngica: relato de 15 casos. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringologia, 63 (1): 48-54, 1997.

14. PINTO LEITE, A.; COSTA, JR. C.; GOUVEA, M.; PINTO LEITE, C.; PORTAL, J.; OLIVEIRA, J. - Sinusites mycotiques. Aport de la tomodensitometrie.Ann.Radiol. (Paris) 35(1-2):73-6, 1992.

15. STAMMBERGER, H. - Endoscopic surgery for mycotic and chronic recurring sinusitis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol., 10:111, 1993.

16. WIATRAK, B. J.; WILLGING, P.; MYER, C. M.; COTTON, R. T. - Functional endoscopic sinus surgery in the immunocompromised child. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 105(6): 81825, 1991.

* Ph.D. Head of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo.

** Resident Physician of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo.

*** Radiologist at Hospital Santa Catarina - São Paulo.

**** Master Degree in Otorhinolaryngology with the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Santa Casa de São Paulo.

***** Physician at Hospital Sírio-Libanês.

****** Physician at Centro de Estudos de Otorrinolaringologia a Fonoaudiologia do Hospital Edmundo Vasconcelos.

Study conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Santa Casa de São Paulo and Hospital Sírio-Libanês.

Address for correspondence: Departamento de Otorrinolaringologia da Santa Casa de São Paulo - Rua Cesário Mota Júnior, 112 - 4° Andar - 01277-900 São Paulo/ SP

Tel/fax: (0xx11) 222-8405.

Article submitted on July 12, 1998. Article accepted on September 2, 1999.