INTRODUCTIONHeadache has a number of etiological factors - among them, some are related with ENT, especially with Rhinology. It is known that both the middle turbinate and the septum are innervated by anterior ethmoidal nerve3,4. If mechanically stimulated, they cause pain on the medial edge of the supraorbital region10.

Medium turbinate has a number of functions, among them lamination of airflow, conduction of inspired air into the olfactory epithelium, moisturizing and heating of inspired air. In addition, it is in direct contact with the ostia of paranasal sinuses, what could lead to abnormalities of breathing, olfactory function and sinuses drainage in case it is increased.

Middle turbinate headache syndrome was initially described by Morgenstein and Krieger8 and it is caused by the compression of the middle turbinate against the septum or the lateral wall of the nose, caused by nasal mucosa congestion or pneumatization of middle turbinate (concha bullosa)4,7.

A significantly large number of surgeries have been performed in order to improve symptoms of headache attributed to the middle turbine, that is, partial turbinectomy and middle turbinoplasty, associated or not with the correction of septum deviation.

This study intended to assess the real importance of middle turbinate in headaches and whether middle turbinectomy, associated or not with septoplasty, improved symptoms.

MATERIAL AND METHODWe assessed 11 patients who had had rhinogenic headache and were operated on the Service of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, between June 1995 and December 1998.

Pre-surgical assessment included nasal endoscopy and CT Scan to confirm the diagnosis. Not all patients were submitted to lidocaine test, because during the assessment some of them did not feel pain. We excluded from the study all patients who did not have signs and/or symptoms of rhinosinusitis, nasosinusal polyposis, or any other complaint that suggested temporal arteritis, neuralgia, ischemia or even migraine. Patients underwent surgery (middle partial turbinectomy, followed or not by septoplasty) and they were reevaluated in 1999, answering a questionnaire about symptoms and going through a new nasal endoscopy.

RESULTSThe group of patients consisted of six female patients and five male patients, ranging in age from 15 to 62 years (mean age of 30 years) when the surgery was performed. Out of 11 patients, 4 were submitted to middle partial turbinectomy and 7 were submitted to septoplasty associated with middle partial turbinectomy.

Pre-operative assessment

Pre-operative assessment is summarized in Table 1.

As we can see, the main complaint before surgery was headache described as unilateral or bilateral periorbital or maxillary pain in 9 cases (82% of the cases). There was a case of holocranial headache (9%) and another one of unilateral parietal headache (9%). Headache was presented daily in 9 cases out of 11 patients (82%), every two days in one case (9%) and weekly in another case (9%). Headaches lasted for a mean of 26 months, varying from 2 months to 8 years.

TABLE 1 - Pre-operative symptomatology of patients.

Key: male: male; fem: female

Patients were also assessed as to nasal complaints, and 10 cases (90%) had nasal obstruction and 7 (63%) has posterior rhinorrhea. We preferred to omit other symptoms because of their low incidence.

Patients were then submitted to endoscopy and CT Scan to define the etiology. Findings are described in Table 2.

According to the pathology found, the patient was submitted to surgical treatment - either simple partial middle turbinectomy or the procedure associated with septoplasty, after unsuccessful strict clinical treatment. The detailed distribution of pathologies found in each patient, as well as the surgeries conducted in each patient are presented in Table 3.

Post-operative assessment

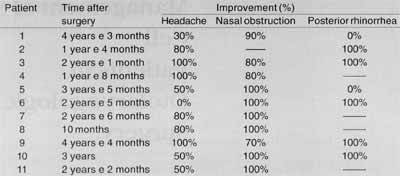

Table 4 shows post-operative assessment.

The follow-up period of patients varied from 10 months to 4 years and 4 months, 30 months in average.

As we can see in Table 4, 3 patients (27%) showed total improvement of headache; three cases (27%) had an 80%improvement; three (27%) a 50%-improvement; one (9%) had only a 30%-improvement and one (9%) did not have any improvement at all after the surgery.

As to nasal complaints, 5 out of 10 patients who had nasal obstruction maintained their complaint (50% of the cases), despite the fact that it had lessen in severity (80%-improvement) and 2 out of 7 patients (28%) maintained the complaint of post-nasal discharge.

In one patient who did not improve after partial middle turbinectomy, we detected through nasofibroscopy a small polyp on the left sphenoid recess. All other patients did not present any other relevant findings at nasofibroscopy.

DISCUSSIONHeadache may be a very frustrating symptom both for the physician and the patient. Many cases are difficult to be diagnosed and even more difficult to be treated. The diagnosis of classical headache may be obvious, such as the case of sensorial headache, migraine and acute rhinosinusitis. However, there are headaches of less obvious origins, which are much more obscure types and require strong clinical evidence. Rhinogenic headache is one of them: its probable cause is the contact between the middle turbinate and the lateral wall or septum, stimulating the sensorial portion of trigeminal nerve. This kind of headache is characterized by periorbital pain, more specifically on the medial supraorbital edge or temporal-zygoma region; it is normally unilateral and intermittent, associated with nasal congestion, it lasts for hours and is frequently present. It is less intense when the patient is in vertical or supine position, pointing the painful side downwards. The nature of this pain is yet to be defined. Greenfield2 (1990) reported the theory that fibers of trigeminal nerve on the nasal mucosa would reach the cortex together with afferent fibers, from the cutaneous portion of the nerve, explaining the facial pain sensation after nasal stimulus. He suggested that the regions in contact should be associated with local engorgement reflex and release of amine vasoactive substances that cause pain. Stamberger and Wolf9 (1988) described them as neuropeptides, and it seems that substance P may be especially involved in the mediation of facial pain, due to its contact with the mucosa.

TABLE 2 - Pathologies found in patients with headache and it is distribuition.

TABLE 3 - Diagnosis and surgery conducted in each patient.

Key: CB: concha bullosa; PL: lateral wall; DS: septum deviation; HCM: hypertrophy of middle turbine; TMP: partial middle turbinectomy; DS: septum deviation; D: right; E: left.

All patients in our study were submitted to CT Scan and nasofibroscopy, demonstrating the presence of concha bullosa or hypertrophied middle turbinate in contact with either the nasal septum or the lateral wall.

TABLE 4 - Improvement of severity of symptomatology after surgery (headache, nasal

obstruction and posterior rhinorrhea) - assessed in percentage.

Despite the fact that they were continuously clinically treated with anti-histamine and topic corticoid, patients did not experience relief of headache; consequently, they agreed to be submitted to surgery. Curiously, within 6 months post-op, patients had a significant improvement of headache, a nearly total relief that resulted in discharge from ambulatory follow-up. Our aim was to assess them in the long run, to make sure that the improvement would prove to be permanent. In fact, they still had significant improvement of symptoms, but not total remission: six patients (54%) had at least an 80%-improvement, and 9 patients (81%) had at least a 50%-improvement. As to nasal obstruction, in 50% of the cases there was total remission, whereas in the other 50% the improvement was not significant (at least 70%, 80% in average). Posterior rhinorrhea was improved in 71% of the patients.

Such results indicated that middle turbinectomy, associated or not with septoplasty, if well indicated, is an effective method to improve symptoms. We would like to point out that the procedure is quite simple, without complications, provided that it is well performed. However, proper diagnosis is critical and it is also important to make the patient understand that the surgery may not result in total relief of symptoms but that there is a significant improvement in the long run.

CONCLUSIONThis study allowed us to conclude that partial middle turbinectomy is an effective procedure to improve headache and that it does not generate complications, provided that it is well performed.

REFERENCES1. ANSELMO-LIMA, W. T.; GONQALVES, R. P. - Anatomia e fisiologia do nariz a seios paranasais. In: Costa SS, Oliveira JAA, eds. Otorrinolaringologia-Princípios a Pratica. Porto Alegre: Editora Artes Médicas; 1994: 289-294.

2. ANSELMO-LIMA, W. T.; OLIVEIRA, J. A. A.; et al. - Middle turbinate headache syndrome. Headache. 1997; 37 (2): 102106.

3. BECKER, S. P. - Anatomy for endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am., 1989; 22: 677-682.

4. BLAUGRUND, S. M. - The nasal septum and concha bullosa. Otolaryngol. Clin N. Am., 1989; 22: 291-306.

5. Chow, J. M. - Rhinologic Headaches. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg., 1994; 111: 211-218.

6. GERBE, R. W.; FRY, T. L.; FISCHER, N. D. - Headache of nasal spur origin: an easily diagnosed and surgically correctable cause of facial pain. Headache. 1984; 24: 329-330.

7. GOLDSMISH, A. J.; ZAHTZ, G. D. - Middle turbinate headache syndrome. Am. J. Rhinology, 1993; 7: 17-23.

8. MORGENSTEIN, K. M.; KRIEGER, M. K. -Experiences in middle turbinectomy. Laryngoscope, 1980; 90: 1596-1603.

9. SILIMY, O. E. -The place of endonasal endoscopy in the relief of middle turbinate sinunasal headache syndrome. Rhinology, 1995; 33: 244-245.

10. WOLFF, H. G. - The nasal, paranasal and aural structures as sources of headache and other, pain. In: Wolff HG, ed. Headache and Other Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 1948:532-560.

* Resident Physician of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto.

** Ph.D. and Professor of the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology at Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto.

Study conducted at the Discipline of Otorhinolaryngology, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto - Universidade de São Paulo and presented at I Congresso Triológico de Otorrinolaringologia, held in São Paulo/ SP, November 13 - 18, 1999.

Address for correspondence: Profa. Dra. Wilma T. Anselmo-Lima-Departamento de oftalmologia a Otorrinolaringologia Do Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto

Avenida Bandeirantes, 3900 - 14096-900 Ribeirão Preto/ SP - Tel: (55 16) 602-2862 / 602-2863 - Fax: (55 16) 633-0186.

Article submitted on February 9. 2000. Article accepted on May 25, 2000.